Forward

Where Hospitality Met History,

Chicago’s Grand Welcome

Before Chicago became the city of steel, jazz, and skyscrapers, it was a frontier town with muddy streets and a dream. That dream found its most elegant expression in the rise of its hotels—palaces of comfort, commerce, and civic pride. From the humble Sauganash Hotel in 1831, where travelers found respite at Wolf Point, to the opulent Tremont House, where Lincoln and Douglas once addressed crowds from its balcony, Chicago’s early hotels were more than lodgings—they were history stages.

This section invites you to stroll through a timeline of architectural ambition and social transformation. Discover how the Great Fire of 1871 didn’t just destroy—it cleared the canvas for a new era of hotel design, culminating in the “Big Four” post-fire marvels: the Palmer House, Grand Pacific, Tremont, and Sherman House. These weren’t just buildings; they were declarations of Chicago’s resilience and cosmopolitan spirit.

By the time the World's Columbian Exposition arrived in 1893, the city boasted over 1,400 hotels and lodging houses. Whether you’re drawn to the grandeur of the Stevens Hotel (once the world’s largest), the lakeside elegance of the Drake Hotel, or the postcard-perfect charm of long-lost second-class inns, this chronology offers a window into the soul of a city that always knew how to roll out the welcome mat.

So unpack your curiosity, check in with wonder, and let Chicago’s hotel history sweep you off your feet.

1700 AD

Along animal migration trails, Indian paths, and later stagecoach routes, the created stops and stations became the foundation for the settlement and growth of many hamlets, villages, and towns in Illinois and the U.S. Territories. For longer trips, overnight accommodations were necessary to complete the journey. Experienced women travelers carried a bag with "necessities" just in case a short trip turned into an overnight fiasco.

The first taverns in Chicagoua (Allium Tricoccum,) the native garlic plant in the onion family, began in the 1820s as log structures. Guests were served a dinner and breakfast, typically consisting of sweetened bread, which was included with the overnight stay. The taverns sold a large quantity of beer, whiskey, and liquor to drink on-site and also offered a selection of beer to take home. The saloon's favorite snacks were very salty ("keeps 'em drink'n"), pickled eggs, pickled pig's feet, and Jerky. The accommodations were basic: a bed, a bite to eat, a roof over your head, a clean outhouse, and a stable, perhaps horse services; food, water, a brushing, and a stall with a horse blanket.

Taverns, hotels, and boarding houses had no clear distinction between them during this era.

1823

The Wolf Point Tavern was familiarly called Rat Castle or Old Geese's Tavern; later names were Taylor's Tavern, Traveler's Home & Western Stage House. It was the first public house in Chicago, opened in 1823 by James Kinzie, John Kinzie's son, and David Hall on Wolf Point [now West Wacker Drive and Canal Street]. A sign with a painted wolf hung on a wooden post by the door, but there was no name written on the sign. The tavern sign was believed to be the work of Lieutenant Allen from Fort Dearborn. The Tavern was later rented to Archibald Caldwell, who obtained Chicago's 1st tavern license on December 8, 1829. A night's lodging costs 12½ ¢ plus 13¢ per horse for stable services: feed, water, a brushing, and a stall with a horse blanket.

Early in 1830, Elijah Wentworth, Sr. [nickname: "Old Geese"] took over the management, paying Kinzie $300 per year until 1832. It was often referred to as Old Geese's Tavern during those years. Alternatively, the early settlers referred to it as Rat Castle, even though it was the best-run Tavern in town. In June 1832, Charles Taylor and his wife, Mary, rented and ran the business for about a year, during which it served as General Scott's headquarters during the 1832 Black Hawk War. The Tavern was referred to as Taylor's Tavern. In 1833, Chester Ingersoll bought and operated the Tavern under Traveler's Home and Western Stage House. It ceased to be a public house in 1834.

|

| Wolf Point Tavern |

1825

Robinson's Tavern & Store, Mr. Alexandre Robinson adapted an Indian store near Wolf Point. He obtained a liquor license on June 9, 1830, and added a tavern. Also, in 1830, this location became part of block 29, and Robinson purchased lots 1 and 2 from the government.

1827

The Miller House, aka Miller's Tavern, was originally a log cabin built in 1820 by Alexander Robinson on the projection of land between the north branch and the main channel of the Chicago River opposite Wolf Point.

In 1827, Samuel Miller and his brother John, with Archibald Clybourn holding a partnership interest, added a two-story house to the cabin, fronting the river.

John Fonda and Boiseley stayed there in January 1828. Initially used as a store and then as a "hotel" for travelers, the structure soon became a traditional tavern, licensed on April 13, 1831. When Sam Miller moved to Elkhart, Indiana, after his wife's death in 1832, P.F.W. Peck moved in with goods and managed a store.

In the December term, 1825, Peoria County commissioners established Chicago Precinct and laid out its boundaries. The Peoria County commissioners' court fixed the prices at which taverns should sell whisky and other alcoholic beverages. Eight dollars was the usual annual license fee for taverns; five received permits to operate in the Chicago Precinct of Peoria County. Archibald Clybourn and Samuel Miller, jointly, were the first to be licensed by Peoria commissioners. The record, entered at a special term on May 2, 1829, reads:

"The Chicago Precinct ... ordered that license be granted to Archibald Clybourn and Samuel Miller to keep a tavern [The Miller House] at Chicago in this state and that the clerk take Bond & Security of the parties for $100 ($3,200 today), and $8 for [the Liquor] License."

Laughton's Tavern. David and Bernardus Laughton established a trading post and Tavern in the late 1820s near the confluence of Salt Creek and the Des Plaines River (Lyons).

1829

The Eagle Exchange Tavern, later renamed Sauganash Tavern and then the United States Hotel, opened in 1829 on the east bank of the South Branch of the Chicago River, in the middle of Lake Street. Mark Beaubien bought a log cabin in 1826 or 1827 from James Kinzie. When the streets were laid out in 1830, he had to move the building slightly south onto the S.E. corner of Market Street [North Wacker] and Lake, onto lots three and four of block 31, which he then bought in 1831. A two-story, large frame house was added, and the establishment became the Sauganash Hotel.

Emily Beaubien recalled that her father, Mark, sold Indian goods in a little log store. He bought the cabin and later incorporated it into the Eagle Exchange, and he was the first to have a billiard table in a public house.

The Sauganash Hotel was named for Billy Caldwell (Sauganash) [SAKONOSH] and opened in 1831. The location at the southeast corner of West Lake Street and North Wacker Drive (now Market Street) was designated a Chicago Landmark on November 6, 2002.

sidebar

In 1835, Mr. Davis assumed control of the hotel, which was subsequently managed by a series of proprietors. The building briefly served as Chicago's first theatre and hosted the first Chicago Theatre Company in November 1837 in an abandoned dining room. By 1839, it returned to service as a hotel but was destroyed by fire in 1851.

The Wigwam (Indian: 'temporary shelter') was built in its place in 1860.

|

| The Eagle Exchange Tavern is on the left, and the two-story addition is the Sauganash Hotel at the SE corner of Market and Lake Streets. |

1830

sidebar

James Thompson surveyed and platted the hamlet of Chicago, which by 1820 had a population of 100 or fewer inhabitants. Historians regard the August 4, 1830 filing of the plat as the official recognition of a location known as Chicago.

Heacock's Point was on the south branch of the Chicago River, South of Hardscrabble [Bridgeport]. Russell Heacock took up land on the south fork of the south branch of the Chicago River near Thirty-Fifth Street today. Heacock was staunchly independent, which is probably why he had moved to the Hardscrabble area (Bridgeport today) in the first place. He opened Heacock's Point, a hotel and Tavern, in 1830.

He needed to move closer to Chicago so that his children could attend school. Heacock himself was one of Chicago's early school teachers. Heacock retained his Hardscrabble property after moving to Chicago.

Heacock is notable for two reasons. First, he was the sole dissenter when a vote was called to incorporate the Town of Chicago (1832). The second thing was his promotion of the Illinois and Michigan Canal. Because funds to build the canal were scarce, a plan was devised to reduce its cost by lowering the intended depth of the channel. Russell Heacock was perhaps the most vocal proponent of this plan, earning him the nickname "Shallow-Cut." Perhaps he disliked the nickname, but the shallow-cut plan was ultimately successful.

Mann's Tavern, on the Calumet River.

The Buckhorn Tavern, aka Laughton's Tavern, was located on the west side of the Des Plaines River on Plainfield Road in Lyons. Plainfield Road was one of the main trails connected with the Ogden Avenue Trail at Lyons. David and Bernardus Laughton are known to have settled on the site in 1827 or '28.

Elijah Wentworth, Chicago's first letter carrier, brought the mail from Fort Wayne before there was a post office in Chicago. Wentworth moved to Lyons in 1830 and kept the Buckhorn Tavern," which was on Plainfield Road, southeast of Hinsdale. The Buckhorn Tavern accommodated weary travelers from Fort Dearborn to Joliet on the stage road.

1831

The Mansion House was built in 1831 by Dexter Graves on the corner of Lake and Dearborn streets. Graves sold to Edward Haddock [his later son-in-law] in 1834, who sold the Hotel to Abram A. Markle in 1835. An August 7, 1835, ad in the Chicago American was referred to as the "Cook's Coffee House." In 1837, Jason Gurley managed the Mansion House. The Hotel was later moved at least twice but was destroyed by the 1871 Great Chicago Fire.

1832

sidebar

My articles below, demonstrate the difficulty of Stage travel, even on beautiful sunny days. Keep in mind that when it rained in Chicago the area turned swampy making any kind of travel a difficult challenge. (Example; Ridge Avenue and Boulevard on Chicago's northside ran along the top of a ridge formed by prehistoric glaciers. It was part of the rim of a massive prehistoric lake geologists call Lake Chicago.)

"The traveler who embarks upon an extended journey by Stage

Committed himself to a venture whose outcome no man could foresee."

Frink & Walker Stage Line Company of Chicago. (est. 1832)

1833

sidebar

Chicago had only twenty-eight voters who could participate in the organization of the local government in 1833.

sidebar

Chicago was incorporated as a town on August 12, 1833, with a population of about 350.

The Green Tree Tavern was later renamed the Chicago Hotel, and then the Lake Street House. It acquired its name from a solitary oak tree nearby. Built by Silas B. Cobb for James Kinzie as a two-story frame building in 1833 that stood at the N.E. corner of what is now Lake and Canal Streets. The structure had low ceilings and doors, and the windows were set with tiny panes of glass. It was managed by a succession of landlords, initially by David Clark and then by Edward Parsons. It was later called the Chicago Hotel [as early as December 1833], then the Lake Street House in 1849. The building was relocated to Milwaukee Avenue in 1880 and subsequently fell into disrepair.

Mark Beaubien managed the Sauganash Hotel in 1836, renaming it "United States Hotel," until, in 1837, he built his own United States Hotel west of the river at the corner of West Water and Randolph Streets.

|

| The Green Tree Tavern, Chicago. 1833. |

Walker's House, Wolf Point, 1833. It was listed as Walker's House and misidentified as a hotel. As it turns out, Walker's House was actually Father Walker's House. Father Walker may have rented a room, but there is no information available about the exact location of Walker House or whether it functioned as a hotel.

Tremont House I, the original Tremont Hotel, was built in 1833. It was a three-story wooden structure located at the northwest corner of Lake and Dearborn streets, and it was destroyed by fire in 1839. It was established by Ira Couch, who took the name from the Boston Tremont House.

Dexter Graves' Boarding House opened in 1833.

Brown's Boarding House opened in 1833. Charles Cleaver remembers his arrival in Chicago on October 23, 1833. We turned north and made for the center of the village, between Franklin and LaSalle Streets, near the river. Here, we had to wait an hour or two until we could find a place to spend the night. We finally found shelter under the most fashionable 16×24 foot log boarding house, kept by a Mrs. Brown.

About forty people ate at Mrs. Brown's daily—how many slept there? I could not say. I know they took in our party of sixteen on the first night in Chicago and set the table for breakfast, served until about dinnertime (noon), until suppertime for the day's main and last meal.

1834

A Bit About Hotel Dining & Entertainment in ChicagoThe first public professional performance in Chicago took place in 1834. It cost 50¢ for adults, 25¢ for children and seniors 28 or older enter for free (jk). The show was staged by a Mr. Bowers, who promised to eat “fire-balls, burning sealing wax, live coals of fire and melted lead.” Somehow, he also did ventriloquism. Other traveling showmen passed through over the next two years; a circus pitched its tent on Lake Street in the fall of 1836. But it wasn't until 1837 that the first local theatre company, "The Chicago Theatre," was established (the famous Chicago Theater we all know and love opened in 1921).The 1960s brought dinner theatre to the forefront of entertainment in Chicago. Dinner's entertainment ranged from small musical groups, big bands, orchestras, and famous entertainers with dinner, then dancing to live music late into the night. The Drake Hotel in Chicago's Gold Coast neighborhood, hosted a live nightly radio show from the Camellia House Restaurant in the 1950s and '60s.

The Exchange Coffee House was later called the Illinois Exchange and sometimes the New York Exchange. Built in 1834, it's the second Hotel built by Mark Beaubien. The Exchange Coffee House was located at the N.W. corner of Lake and Wells Streets and was initially run by Mr. and Mrs. John Murphy. Subsequent managers or owners were A.A. Markle in 1836, Jason Gurley in 1838, and Charles W. Cook in 1839.

Stiles' Tavern, on the south branch of the Chicago River, opened in 1834. Stiles' Tavern was especially noted for its matrimonial facilities.

The Pre-Emption House, Naper's Settlement [Naperville].

The Pre-Emption House was built in 1834 on Main Street and Chicago Avenue in Naper's Settlement [Naperville]. It was the first hotel and tavern west of Chicago. It was named after a federal law that allowed settlers to reserve up to 160 acres of land.

A steady stream of easterners and immigrants journeyed west to claim land sold for just $1.25 an acre. Settlers passing through town on the north-south or east-west stagecoach routes kept business brisk. The Pre-Emption House offered a traveler a shot of whiskey, a bed for the night, and breakfast, plus feed and stabling for their horse, all for 35¢. It was torn down in 1946.

In the Pre-Emption House tavern, locals conducted business deals and celebrated with dances. They ate meals in the dining room. The Pre-Emption House hosted official government business before constructing the first DuPage County courthouse in Naperville in 1839. Monthly Horse Market Days were held in front of the hotel, drawing farmers and dealers from all over to buy, sell, and showcase their horses. It was torn down in 1946.

|

| The original Pre-Emption House and Tavern is located in Naperville, on the corner of Main Street and Chicago Avenue. Built in 1834, it was one of President Lincoln's most comforting stops. |

Hobson House & Tavern was a Greek Revival-style house that doubled as the Hobson Tavern on the west branch of the DuPage River.

|

| The Hobson House, the three-story building, also hosted the Hobson Tavern. |

1835

sidebar

The Lake House Hotel served oysters in a number of different ways on the menu in 1835. I explain some of the transportation issues involved in getting fresh, live oysters to Chicago at first.

sidebar

A Teen Girl's Opinion of Chicago as Written in 1835.Ellen Bigelow, a young woman in her late teens, arrived at Chicago with her sister, Sarah, on the Illinois brig on May 24, 1835. Fourteen days out of Buffalo, New York. The daughters of Lewis Bigelow, a lawyer from Petersham, MA, moved to Peoria several months earlier with other family members. The girls left Chicago the following day by stage, arriving two days later in Peoria.Within a month, Ellen detailed their arduous journey in a letter to an aunt, and that relevant to Chicago follows: "Chicago I don`t like at all. The town is low and dirty, though situated advantageously for commercial purposes. I saw only one place where I would live if they gave me all their possessions, and that was at Fort Dearborn. I liked that. It is beautifully situated, and the grounds and buildings are neat and handsome. A great land fever was raging when we arrived there, and I am told it has not yet abated. Property changes hands there daily, and it is thought no speculation at all if it doesn`t double in value by being retained one night. I think they are all raving distracted, and if I'm not mistaken, in a few years, if not months, will reduce things to their proper level and restore them to their senses."

sidebar

In the winter of 1835 and 1836, weekly dancing parties were inaugurated at the Lake House, and four-horse sleighs and wagons were sent around to collect the ladies who attended them. From this time society seemed to take upon itself amore decided form, rising from the chaos in which it had been before.

The Steamboat Hotel, later known as the American Hotel or American Inn, opened in 1835 on North Water Street, near Kinzie Street, and was operated by John Davis. On November 9 that year, J. Dorsey and J. Force announced in the Chicago Democrat that they had assumed management and "nothing shall be wanting to render their House worthy of a call from a few of the many who visit this flourishing village." It was renamed the American Hotel, also known as the American Inn, in 1836 when it was acquired by William McCorristen.

|

| The Steam Boat Hotel was renamed the American Hotel in 1836. |

The Lake House Hotel was the Chicago region's first luxury hotel, and its Lake House Restaurant was the first fine dining establishment to open in 1835. The restaurant used menu cards, and the tables were set with a tablecloth, napkins, quality silverware, and glassware. Dinner was served in courses, and the meal ended with dessert and a damp napkin. Toothpicks were already on the table. Fresh-caught fish from Lake Michigan and other local fishing spots were on the daily menu. The Lake House Restaurant holds another Chicago' first' record. They were the first in the area to offer fresh oysters on the menu. The oysters were transported on a schedule from New England by sleigh in 1835.

By 1850, the Lake House no longer functioned as a hotel but had become a charitable hospital for the poor, initially with 12 beds. In December of that year, the Order of Sisters of Mercy members assumed responsibility for nursing care. Among the attending physicians was Dr. Daniel Brainard, who provided free care in exchange for the privilege of conducting teaching sessions with his Rush Medical School students on the premises. Thus, Lake House became Chicago's original Mercy Hospital site and retained that purpose until October 1953, when they moved to a new brick building on Wabash Avenue and Van Buren Street.

|

| Looking N.E. at the Lake House Hotel and the Lake House Restaurant at the foot of the Rush Street Bridge, circa 1857. |

Newton's Hotel & Tavern opened in 1835. Hollis Newton owned a 48-acre plot where he ran a roadside hotel and Tavern three miles south of Chicago's border. He died on August 25, 1835, two months after the hotel opened.

NOTE: In 1835, Chicago's southern border was 22nd Street (now Cermak Road).

The Western Hotel opened in 1835. It was a small structure built and operated by W.H. Stow on the S.E. corner of Canal and Randolph streets.

Planck's Tavern, located in Dutchman's Point (Niles, IL), was established in 1835 by John Planck (or "Plank"), who moved there in 1834. The tavern was situated 12 miles northwest of the Chicago River, on the Milwaukee Road (also known as the "Northwestern Plank Road," completed in 1851), in Niles Township.

1836

sidebar

The population of Chicago, according to the last census, was 3279. In 1836, there were 44 stores (dry goods, hardware and food groceries), 2 book stores, 4 druggists, 2 silversmiths and jewelers, 2 tin and copper manufactories, 2 printing offices, 2 breweries, 1 steam sawmill, 1 iron foundry, four storage and forwarding houses, 3 taverns, 1 lottery office, 1 bank, 5 churches, 7 schools, 22 lawyers, 14 physicians, a lyceum (secondary school) and a reading room. Nine brick buildings have been erected the past season: a three-story tavern and a county clerk’s office.

American Hotel (aka American Inn) North Water Street at Kinzie Street, 1836-1839 (see: The Steam Boat Hotel, 1835)

Castle Inn, Brush Hill Trail, [Hinsdale], opened in 1836.

Ellis Inn opened in 1836.

Fay's Boarding House opened in 1836.

Ike Cook's Saloon, also known as Cook's Coffee House, was located on the north side of Lake Street, near Dearborn, and opened in 1836. (see The Mansion House, 1831)

Kelsey's Boarding House opened in 1836, close to the lakefront. It was a small yellow house owned by Parnick [Patrick] and Eve Kelsey, who ran it as a boarding house.

Kettlestrings' Tavern: In the 1830s, the Kettlestring family purchased 170 acres just west of Chicago. This quarter section of land was known as Kettlestrings' Grove, then Oak Ridge Inn, then Harlem, and finally, Oak Park today.

In the 1850s, the family began selling large parcels of their land holdings to those who followed the first train to run West of Chicago. The railway station was eventually named Oak Park. While Oak Park became the area's official name, it remained unincorporated and was officially part of Cicero Township until 1902.

The Patterson Tavern, [Winnetka]. In 1836, Erastus and Zeruah (also known as Zernah) Patterson, along with their five children, traveled west from Vermont as part of an ox-drawn wagon train comprising six families. The group camped on the hill at the site now known as Lloyd Park in Winnetka. While the five other families continued their journey, the Pattersons decided they had arrived at a beautiful and ripe spot for commerce. They settled on the stagecoach route, the "Green Bay Trail," which connected Chicago's Fort Dearborn, Milwaukee, and Fort Howard in Green Bay, Wisconsin.

Patterson built a log house along the new stagecoach stop in 1836 and opened the Patterson Tavern. Wayfarers could warm themselves or cool off, depending on the season. They could also buy a drink or a meal, rest and feed their horses, and stay the night before resuming their journeys.

Erastus Patterson died the following year. "Widow" Patterson ran the Tavern with her sons until 1845, becoming one of the first women in the area to operate a business. She sold the Tavern to Lucas Miller, who sold it to Marcus Gilman a short time later. Gilman sold it to John Garland, a prominent early settler, in 1847.

Rexford House, Blue Island, opened in 1836.

Rice's Coffee House, Lake Street, opened in 1836.

The Halfway House, aka Dr. Wright House, [Plainfield] 1836. Plainfield was first settled in the 1820s by a group seeking to convert the local Potawatomi to Christianity. Squire L.F. Arnold, the first postmaster of Plainfield, owned the tract of land on which the building stands. In 1834, he built a small building to serve as a post office and a stop for stagecoaches.

The property was sold in 1836, and a two-story building was constructed adjacent to the original structure. This new structure operated as a tavern and Inn. The Inn earned its name by being halfway on the stagecoach line between Chicago and Ottawa. A year later, Dr. Erastus Wight became the manager of the Halfway House, where he remained until he died in 1845. His son, Dr. Roderick Wight, took over from his father and purchased the building in 1850. Later that year, he added a one-story addition to the back of the Inn.

The Inn's large size made it an ideal site for town affairs. It was used as a meeting hall in its early years and became the primary location for Plainfield social events. The Plainfield Light Artillery used the building as its headquarters from 1856 until the outbreak of the Civil War. The building ceased to function as an inn in 1886 and was converted into a private residence. It was home to the descendants of the Wight family until 1956. The original building that served as a stop for stagecoach passengers was demolished in the 1940s. The remaining building was added to the National Register of Historic Places on September 29, 1980.

The New York House opened in 1836. Professional dance instructor Mr. Jackeax hosted a weekly dinner and dance school at the New York House Restaurant. The perfect evening out... fine dining, quality wines, liquors, desserts, and then dancing. Jackeax's events were known as first-rate and catered to the city's elite.

1837

sidebar

With a population of 4,170, the town of Chicago filed new Incorporation documents on March 4, 1837, becomming the City of Chicago and for several decades was the world's fastest-growing city.

The City Hotel (1837-58) - The Sherman House I (1858-73)

The City Hotel was a large three-story brick structure constructed by Francis Cornwall Sherman. They opened in 1837 on the N.W. corner of Clark and Randolph streets.

In 1839, Sherman retired from managing the Hotel, handing over management to the firm of James Williamson and A.H. Squier. Williamson retired from the firm the following year, and William Rickards acquired his interest. The proprietorship of the Hotel remained in possession of Rickards and Squier until 1851, when they sold their proprietorship to the firm of Brown & Tuttle. In 1844, the hotel underwent a remodeling project, and two additional stories were added. In 1854, the firm became Tuttle & Patmor when A.H. Patmor acquired Brown's share in that firm. In 1858, the proprietorship was acquired by Martin Hodge and Hiram Longly, and the City Hotel was sold, becoming the future Sherman House Hotel.

.jpg) |

| The First Sherman House in 1858. |

Francis Cornwall Sherman built a new structure on the City Hotel lot, breaking ground on May 1, 1860, and named it the Sherman House, also known as Hotel Sherman. The Grand Opening welcomed the first guests on July 1, 1861.

The Sherman House II was designed by William W. Boyington and operated by George W. Gage. It became one of the city's grand hotels alongside the Tremont House. The front of the building was made of Athens marble on the levels above its storefronts. Its primary entrance was along Clark Street, with a two-story portico. To the right of the main entrance was the building's ladies' entrance. The building, which was 161 feet long along Randolph Street and 181 feet long along Clark Street, featured an open court in its center and rose six stories. A western section of the building along Couch Place rose seven stories. The building was designed in modern Italian style. The Hotel was lost in the Great Chicago Fire in 1871.

|

| The Second Iteration of the Sherman House Hotel in 1861. |

The Little Sherman House. When the Great Fire of 1871 destroyed the Sherman House, the owners leased the building at 39 West Madison and Clinton Streets, which had just been completed and was known as the "Little Sherman House" until the new Sherman House was built. It was afterward known as the Gault House until the Gault House management built their new hotel at Madison and Market Streets.

The Sherman House Hotel III, at 151 Monroe Street. Francis Cornwall Sherman rebuilt his Hotel. From 1872 to 1873, the Hotel's third structure was constructed at the same site as the previous hotels. The third Hotel, as with the second, was designed by William W. Boyington. The building was 160 feet long along Randolph Street and 181 feet long along Clark Street. As with the previous building, the entrance was located along Clark Street. The ladies' entrance was along Randolph Street. The building had a courtyard and featured fireproof vaults. The building was constructed from grey sandstone from a newly opened quarry in Kankakee, Illinois. The building was 115 feet tall. It contained 300 luxurious rooms, including suites. The hotel became the Chicago headquarters of the Democratic Party. In 1904, Joseph Beifeld became the owner of the Hotel. Three generations of the Sherman family operated the Hotel. In September 1909, the Hotel closed to be replaced with a new structure.

|

| The Third Iteration of the Sherman House Hotel in 1873. |

The Sherman House Hotel IV was renamed before the Hotel Sherman opened in 1911. A new 757-room Hotel Sherman was designed by Holabird and Roche. Hotel Sherman retained its status as one of the finest hotels in the city from the time it opened, a reputation that lasted into the 1950s. In 1972, a decision was made to strip the building to its steel frame and reconstruct it as a modern building with a glass curtain wall, transforming it into an apparel mart named the "Sherman Fashion Plaza."

1839

The Illinois Exchange, 192 Lake Street, 1839 Chicago Business Directory.

The Mansion House (see Cook's Coffee House - 1831)

Shakspeare Hotel, North Water Street, near the Lake House, 1839 Chicago Business Directory.

1840

sidebar

By the 1840s, the Sauganash Hotel, Mansion House, and the Lake House, at different times, offered an all night "dinner, dancing, and breakfast" event, monthly. Dinner was served at six o'clock, followed by breakfast at seven o'clock the next morning. Some locals would stay overnight because night travel was slow and difficult, especially when inebriated and... is not safe for a lady to be out. Chicago's 1840 U.S. census recorded a population of 4,470 persons.

The Tremont Hotel II was a three-story structure located at the S.E. corner of Lake and Dearborn streets. It was completed in 1840 after the first Tremont Hotel fire.

The Washington House, S.E. corner of Clark and South Water Streets, 1840.

1844

The Michigan Street House, Michigan Street and La Salle, 1844

|

| 1871 Chicago Fire map portion. |

The American Temperance House, [alcohol-free], N.W. corner of Lake Street and Wabash Avenue, Chicago, 1844

The Taylor Temperance House, [alcohol-free],1844

The Farmers' Exchange was near Franklin and Water Streets in 1844

1850

The Tremont Hotel III was constructed on the same site as the second hotel at the Southeast corner of Lake and Dearborn Streets. They opened in 1850 in a five-story brick structure with 260 rooms, designed by John M. Van Osdel. It was a block masonry structure with the finest amenities of the day. The large hotel was initially dubbed "Couch's Folly" by those who expected it to fail. It was once considered the leading hotel in the western United States.

The building was among the largest to be physically raised when Chicago heightened the grade of its streets in the 1850s and 1860s (Raising Chicago Streets Out of the Mud). In 1861, Ely, Smith, and Pullman lifted the Tremont House six feet in the air (George Pullman made his reputation as a building raiser before becoming famous for manufacturing rail sleeping cars). The building was one of many in Chicago that were raised to match the upward-shifting street grade, improving proper drainage during the mid-nineteenth century.

Abraham Lincoln frequently visited Chicago to sit in the U.S. District Court. Like most prominent attorneys and politicians, Mr. Lincoln usually stayed at the Tremont Hotel when in Chicago. In 1855, Chicago boasted a population of 85,000 and 57 hotels.

During the 1858 United States senatorial race in Illinois, Stephen A. Douglas, who regularly stayed at the hotel while in Chicago, delivered a speech on July 9, 1858, that included a rebuke to Abraham Lincoln's "House Divided" Speech. Lincoln, who was in Chicago to attend an opening session of the United States District Court, appeared at the hotel that night to deliver a rebuttal. This marked the beginning of each individual's Senate campaign.

The Tremont served as the headquarters for the Illinois Republican Party during the 1860 Republican National Convention (held at the nearby Wigwam) as they lobbied for Abraham Lincoln's nomination.

Stephen A. Douglas died at the hotel on June 3, 1861.

In 1865, Mary Lincoln stayed at the hotel for one week following her husband's assassination. Robert Lincoln and Tad Lincoln stayed with her during that time.

The hotel burned to the ground during the Great Chicago Fire in 1871.

|

| Tremont House at the S.E. corner of Lake and Dearborn Streets, Chicago. c.1865 |

The Matteson House I, on the N.W. corner of Dearborn and Randolph streets, 1850.

|

| Looking eastward towards Dearborn. The Matteson House I (1850-1871) is under the arrow on the northwest corner of Dearborn and Randolph Streets, Chicago. Note the Chicago Street Paver Bricks. |

The Hamilton House, S.E. corner of Clark and South Water Streets,1850.

1854

The Briggs House, on the corner of Randolph Street and Fifth Avenue (today's Wells Street), 1854. In 1866, the building was raised 4 feet 2 inches from its foundation, Raising Chicago Streets Out of the Mud.

1855

sidebar

The 1855 Chicago City Directory added a new category: Restaurants. As we can see, there are not too many restaurant listings yet, but never fear. Many restaurants were hotel owned or leased from the hotel. Nepotism ran rampant in fine dining restaurants. Think of this time period as Chicago's restaurant gold rush of the [mid]west.Restaurants (Taverns & Saloons serving proper meals.)Clarendon, 214-216 Randolph Street.Commercial Dining Hall, 50 Clark Street.Gill Edmund, North Wells Street at the corner of North Water Street.Hatch Heman, North Wells Street near Kinzie Street.Holway's, 131 Randolph Street.John Boyle's Oyster Saloon, 8 North Clark Street.McCardel, 17-19 Dearborn Street.Maulton's, 192 Randolph Street.Mason's, 133 Randolph Street.Restaurant de Paris, 227 Clark Street.St. Charles, 15-17 North Clark Street.St. Neblo's Hilliard, Hilliard's block - N.E. corner of Clark and South Water Streets.Tremont Exchange, 8 Tremont block - S.E. corner of Lake and Dearborn Streets.Vinton's, 82 Randolph Street.Washington Coffee House, corner of State and Randolph Streets.Oyster Depots (Wholesale).Henry Cooke, 12 Clark Street.J.B. Doggett, 125 South Water Street.

1856

The Foster House, Clark and Kinzie, 1856

The Richmond House, corner of South Water Street and Michigan Avenue, opened in the autumn of 1858. The Prince of Wales selected this Hotel as his place of sojourn during his stay in Chicago.

1857

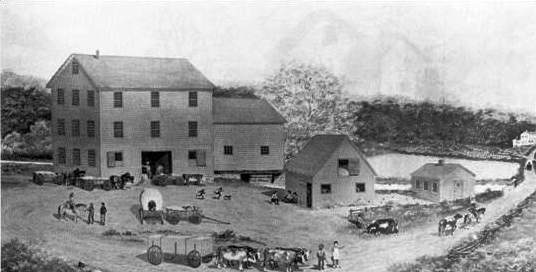

The Adams House was located on the northeast corner of Lake Street and Michigan Avenue. Notably, this hotel stands on the former site of the old Hydraulic Mills, the first flour mills in Chicago, which closed in 1853.

"This fine hotel is comparatively a new candidate for favor with the traveling public. It is convenient to business, the Great Central Railroad Depot, and commands a fine view of the Lake and the city's most handsome portion. The proprietor, Mr. W.L. Walter, is an accommodating, courteous gentleman devoted to the comfort and enjoyment of his guests.

The rooms are large, airy, and well-furnished, and the parlors are fitted in a superb, rich style. The table is equal to any first-class hotel in this or the eastern cities, with well-trained and attentive servants attending to guests' wants and needs. With such a desire for a quiet, well-ordered hotel, we can confidently recommend the Adams House."

——Chicago Tribune, November 3, 1858.

ADAMS HOUSE OWNERS

Built in 1857 by Hugh Maher. William Adams, the initial owner, opened the house in the autumn of 1858.W.L. and J.I. Pearce, formerly of the Matteson House, purchased and assumed control of the Adams House. In December 1860, W.L. Pearce sold his interest to Schuyler S. Benjamin from the Brevoort House.Pearce & Benjamin conducted the Adams House until it was destroyed by the Great Chicago Fire in October 1871.

The Boardman House, corner of Clark and Harrison Streets, 1857

The Massasoit House, S.E. corner of Old Central Avenue (Beaubien Court) and East South Water Street, opened in 1857. It was rebuilt after the Chicago fire, opening in 1873.

1858

The Clifton House, 45-47 Madison Street at the corner of Clinton Street, "just across the river." Opened in 1858, it was initially called the Clifton House until 1909, when Samuel Gregsten (Windsor European) purchased the hotel and renamed it the Windsor-Clifton Hotel. It was an extremely well-known "European" hotel of the time.

1859

Wright's Hotel (later, The Moulton House), 1859

The Orient opened in 1859

1860

The Garden City House (A Temperance Hotel), Madison & Market Sts, 1860.

Amos Gager Throop (1811-1894) moved to Chicago in 1843. He began a lumber business in partnership with Solomon Wait and John Throop. Throop also bought and sold residential and commercial real estate, owned a dredging company, a brickyard, a coal company, and speculated in stocks. He purchased and managed the Temperance Hotel in Chicago in 1860, the Garden City House.

Throop founded the Second Universalist Church in Chicago and served in the Illinois House of Representatives from 1863 to 1864. He was a member of the Chicago Common Council and the Chicago Board of Trade.

1862

The Anderson House, 1862

The Central Hotel, 1862

1863

The Sherman House, 139-141 Randolph Street at the N.W. corner of Clark Street, 1863. (See the City Hotel, 1837)

The Burlington Hotel, 1863

1864

Hough House Hotel, Union Stock Yards,1864. The Transit House was renamed and stood on the future Stock Yard Inn site after the 1912 Chicago Union Stock Yard Fire.

The Revere House, on the north side of the Chicago River, at the corner of 417 North Clark and Kinzie Streets, 1864

1865

The St. James House, 92-98 State and Washington Streets, 1865

1866

The Barnes House, corner of Randolph and Canal Streets, 1866

The Metropolitan Hotel, on the S.W. corner of Randolph and Wells Streets, 1866

1870

The Palmer House I, State and Quincy Streets, 1870

In 1869, Potter Palmer began constructing the Palmer House at the northwest corner of State and Quincy Streets. It had imposing stone fronts, was eight stories high, and contained 225 rooms. W.F.P. Meserve was its first proprietor. The Hotel was opened for the accommodation of guests on Monday, September 26, 1871. Thirteen days later, it was a heap of smoldering ruins.

|

| The Palmer House I, (1870-1871) |

The Michigan Avenue Hotel was opened in September 1870 by J.F. Pierson and J.B. Shepard. It contained eighty rooms with luxurious furnishings. In a few months, the proprietors assigned Joshua Barrell, another hotelman, who sold the furniture at public auction to Joseph Ulman and Herman Tobias. On October 8, 1871, flames raged on the north side of Congress Street. John B. Drake offered to purchase the Michigan Avenue Hotel at a stipulated price and assume the risk of its destruction. The offer was promptly accepted.

|

| 1871 Chicago Fire Map - Michigan Avenue, Chicago. |

The Michigan Avenue Hotel was unscathed, and the building was often pointed out as a moment of the flames' cessation in the South Division. Mr. Drake rechristened the Hotel as the Tremont House and conducted it until he took charge of the Grand Pacific Hotel in 1873 after it was rebuilt.

The Gault House, 45-47 Madison Street, is on the corner of Clinton Street (West of the river).

1871

The Bigelow House, a handsome edifice of pressed brick, was erected in 1870-71 at the S.W. corner of Dearborn and Adams Streets by Benjamin H. Skinner. On the very day when it was to have been opened, October 8, 1871, it was destroyed by the great conflagration. Mr. Skinner's losses were substantial and led to his financial ruin.

The Palmer House II, S.E. corner State and Monroe Streets, 1871

The Chicago Fire burned through the South Loop, West Loop, Cabrini-Green, Loop, Near North, Rush & Division, Gold Coast, and Old Town communities. 1871 CHICAGO FIRE MAP.

Other establishments sought temporary quarters. Thus, the Clifton rented the premises at the northwest corner of Washington and Halsted Streets, the Briggs House temporarily reopened on West Madison Street, and so with others.

Rebuilding proceeded at the most excellent possible speed, but knowledge had been dearly bought in the school of experience, and new and improved construction methods were adopted. The result is best evidenced by the fact that since 1871, Chicago has had but one hotel fire, that of the ill-fated "Hotel Langham" in 1885.

The first crucial new house to open its doors (in August 1872) was Kulm's Hotel (afterward the Windsor), on Dearborn Street, a little south of Madison. The impetus was thus given to the "Gault," resulting in that hostelry securing an enviable rank among Chicago hotels. It was built on school land, leased for ninety-nine years by Samuel Gregston, who subsequently became the proprietor.

Next came the Gardner, on Michigan Avenue, at the corner of Congress Street, which opened on October 1, 1872. It was named after H.H. Gardner, who, in connection with Frederick Gould, conducted the house until 1881, when Warren F. Leland became proprietor and changed the name to the Leland Hotel. In 1892, Mr. Leland retired, and a syndicate purchased the property.

The Commercial, on the northwest corner of Lake and Dearborn Street, and the Grand Central, on Market Street, soon followed and later (in 1873) were thrown open the doors of several leading houses, notably the Grand Pacific, the new Palmer, Sherman, Tremont and Briggs.

The proprietors of Briggs reopened at its former location, on the northeast corner of Randolph Street and Fifth Avenue (now Wells Street). At the same time, the Clifton established itself at the intersection of Wabash Avenue and Monroe Street.

A new departure in Chicago hotel keeping was made in January 1885, when H.V. Bemis built and opened the Richelieu Hotel. The house was not significant, occupying the relatively narrow frontage at Nos. 187 and 188 Michigan Avenue, with dimensions of 60 feet by 185 feet. While small, it was undoubtedly the most elegant (and perhaps the most expensive) of Chicago's hostels at that time. Over its entrance stood a marble statue of Jean du Plessis, a famous French sculptor, Cardinal de Richelieu, by Le June. All its equipment was upon a scale of sumptuousness befitting a private mansion whose owner recognized no expense limit.

Guests were served on the finest china produced by the world's most famous potteries. Food was served on solid gold and silver plates, and the choicest vintages of southern European wines were served in heavy-cut glass. The tables were covered with the finest damask (a reversible patterned fabric of silk, wool, linen, etc., with a pattern formed by weaving, table linen, and upholstery. Guests were encouraged to cultivate their aesthetic tastes by viewing fine art paintings of high quality. The house had lost none of its pristine excellence and occupies today a unique position among the world's caravansaries.

The New Tremont House (Temporary Location After Fire).

During the interim period following the 1871 fire, the hotel operated as the "New Tremont House" out of a hotel that John Drake had purchased at Michigan Avenue and Congress, having made a bet that the building would escape the fire. (see Michigan Avenue Hotel 1870 for the full story).

Strangers from every portion of America were constantly visiting Chicago, and the last source of her pride was the ability of her hotels, admittedly the best in the West, to accommodate a vast throng of travelers and cater to their needs. The hotel industry had grown, their numbers had multiplied like rabbits, and rich appointments were constantly approaching perfection. When the ashes cooled, scarcely one of the city's hostelries was not in ruins. The hospitality business was practically wiped out in Chicago's business district.

1872

sidebar

The "Big Four" post-fire hotels included the Palmer House, the Grand Pacific, the Tremont, and the Sherman House. These buildings adopted the commercial palazzo style of architecture typical to the grand hotel palaces of the east coast. All professed to be fireproof! All boasted grand lobbies, monumental staircases, elegant parlors, cafes, barber shops, bridal suites, dining rooms, ballrooms, promenades, hundreds of private bedrooms and baths, and the latest luxuries. Typical room charges ranged from $3.50 ($85 today) to $7 ($170 today) per day and included three meals. Guests incurred an extra charge for private parlors, room service, fires in private fireplaces, and desserts taken from the diner table to one's room.

Hotels like the Palmer House and the Grand Pacific not only served transient visitors but also appealed to wealthy permanent residents who found living in a hotel a convenient way to set up trouble-free elegant households. Hotels such as these served as models for other hotel construction. Chicago also became a center for the hotel industry, with three of the influential hotel trade journals being publishing in the city.

sidebar

The Gault House, situated on Madison Street between Canal and Clinton Streets, was the only hotel of prominence left because it was on the west side of the Chicago River.

The Grand Pacific Hotel II, Between Clark, LaSalle, Quincy, and Jackson, 1872

The Woodruff, corner of Wabash Avenue and Twenty-First Street, 1872

Kulm's Hotel (afterward The Windsor-Clifton Hotel), at the N.W. corner of Wabash Avenue and Monroe Street, 1872

The Windsor-Clifton Hotel, at the N.W. corner of Wabash Avenue and Monroe Street. Opened in 1872, it was initially called the Clifton House until 1909, when Samuel Gregsten (of Windsor European) purchased the Hotel and later acquired the Clifton Hotel. The Windsor-Clifton Hotel was an extremely well-known "European" hotel.

The Windsor-Clifton Hotel, at the northwest corner of Wabash Avenue and Monroe Street, was built in 1872 and razed in 1927 to make way for the Men's Store of Carson, Pirie, Scott & Company. For many years, it was one of Chicago's leading hotels. After De Jonghe's Hotel and Restaurant, the old Chicago Club is seen West of the Windsor-Clifton. It was initially called the Clifton House till 1909, when it was purchased by Samuel Gregsten (Windsor European).

After the great fire, Mr. Gregsten built the Windsor Hotel on Dearborn Street, between Monroe and Madison. This was the first and, for many years, the only European hotel in Chicago, and it did not have a bar during the time Mr. Gregsten was the owner and proprietor. The Windsor was the home of people from small towns and the country, and was preeminently respectable. No man was ever so strict and severe in managing a hotel as Sam Gregsten, who did not hesitate to throw guests out into the street at midnight and return their money upon finding anything wrong or suspicious.

He later purchased the Clifton Hotel, located on the northwest corner of E. Monroe and S. Wabash streets, and renamed it the Windsor-Clifton. This hotel was an extremely well-known "European" hotel of the time.

|

| The Windsor-Clifton Hotel, formerly the Clifton House, on the N.W. Corner of Wabash and Monroe streets. circa 1910 |

1873

Palmer's Grand Hotel [III]

S.E. corner State and Monroe Streets, Opened November 8, 1873

1874

sidebar

The "Little Big Fire" on July 14, 1874, burnt most of the area between Van Buren Street on the north, Michigan Avenue to the East, 12th Street (renamed Roosevelt Road in 1919) on the south, and Clark Street to the west. (Don't miss the 'after-math' analysis discussing the reshaping of some of Chicago's neighborhoods in my "Little Big Fire" article.

The Gardner House, Leiland Hotel, The Stratford, Michigan Avenue, and Jackson, 1874

Burky & Milan, 154-156 South Clark Street (today 20-22 South Clark Street) 1874

1875

The Great Central Hotel, S.W. Corner Market and Washington Streets, 1875

1879

The Gault House, 39-41 West Madison Avenue and Market (today 30 West Madison) 1879

1885

The Leland Hotel, S.W. corner Michigan Avenue and Jackson Boulevard, 1885

1890

The Blackstone, Michigan Avenue, and East Balbo, 1890

1881

The Virginia Hotel, 78 Rush Street at the corner of Ohio Street, Chicago, 1891-1925. It was one of the world's largest and most beautiful privately owned family hotels. The building is a splendid specimen of modern hotel architecture. This is a high-class house in every sense.

|

| Virginia Hotel, Main Entrance, circa 1892. |

Opening just a couple of years before the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition, the 400-room hotel was advertised as "an absolutely fireproof building and a finished hotel second to no other." The hotel featured ornate granite interiors decorated with marble statues, a separate "gentlemen's smoking room," a ladies' dining room," and a room of boilers and dynamos to offer the latest technology: electric lights.

1892

sidebar

1892 Chicago Telephone Directory; Popular HotelsAuditorium Hotel, Wabash Avenue, and CongressClifton House, 159 and 161 Wabash AvenueColumbia Hotel, N.W. corner of 31st Street and State StreetsCommercial Hotel, Lake and DearbornFitzgerald Hotel, Rose Hill, IL. [Bowmanville Neighborhood today]Fredericks, (Henry) House, 4300 South Ashland AvenueGault House, 39 West MadisonGlen Ellyn Hotel, 44 DearbornGore & Heffron, 266 Clark StreetGrand Pacific Hotel, Clark and JacksonGrand Palace Hotel. Clark and IndianaHotel Brevoort, 143-145 MadisonHotel Grace, 243 South Clark StreetHotel Metropole, S.W. corner of 23rd Street and Michigan AvenueHotel Richelieu, 187 Michigan AvenueHotel Wellington, Wabash Avenue, and JacksonHotel Woodruff, 2101 South Wabash AvenueHotel Worth [H. W.], 435 Washington BoulevardKuhn's Hotel, 165-169 Clark StreetLeland Hotel, Michigan Avenue, and Jackson.Palmer House, State Street, and MonroeRevere House, 417 North Clark Street at KinzieSaratoga Hotel, 155-157 DearbornSouthern Hotel, Wabash Avenue and 22nd StreetThe Albany, 2400 [S.] Wabash AvenueThe Hyde Park, S.W. corner of 51st Street and Lake AvenueThe Yorkshire, 1837 South Michigan AvenueTremont House, Lake and DearbornVirginia Hotel, Rush and Ohio Streets

1893

The Auditorium Hotel, N.W. corner Michigan Avenue & Congress Boulevard. 1893.

The Auditorium Hotel's history is connected to the (haunted?) Congress Plaza Hotel opened in 1893 as an annex to the Auditorium Building. It was initially called the Auditorium Annex when it first opened to accommodate visitors to the World's Columbian Exposition. It featured an underground marble passageway called "Peacock Alley," which connected it to the Auditorium Hotel. By 1908, the name changed from the Auditorium Annex to the Congress Hotel to differentiate it from the Auditorium Hotel.

Ferdinand Peck, a Chicago businessman, incorporated the Chicago Auditorium Association in December 1886 to develop what he wanted to be the world's largest, grandest, most expensive theater that would rival such institutions as the Metropolitan Opera House in New York City. He was said to have wanted to make high culture accessible to the working classes of Chicago.

The Auditorium Building in Chicago is one of the most renowned designs by Louis Sullivan and Dankmar Adler. Completed in 1889, the building is situated at the northwest corner of South Michigan Avenue and Congress Parkway (now known as Ida B. Wells Drive). The building was designed as a multi-use complex, featuring offices, a theater, and a hotel. Frank Lloyd Wright was employed as a draftsman as a young apprentice and may have contributed to this design.

Housed in the building around the central space was a 1890 addition of 136 offices and a 400-room hotel, whose purpose was to generate much revenue to support the opera. While the Auditorium Building was not intended as a commercial building, Peck wanted it to be self-sufficient. Revenue from the offices and hotel was meant to make ticket prices reasonable. In reality, the hotel and office block became unprofitable within a few years.

The building was added to the National Register of Historic Places on April 17, 1970. It was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1975 and was designated a Chicago Landmark on September 15, 1976. In addition, it is a historic district contributing property for the Chicago Landmark Historic Michigan Boulevard District. Since 1947, the Auditorium Building has been part of Roosevelt University.

1897

The Silversmith Hotel, Wabash Avenue and Madison Street (today, 10 South Wabash),1897. The Silversmith Hotel was a boutique hotel in Chicago's Jewelers Row District of the Loop. It occupies the historic 10-story Silversmith Building, designed by Peter J. Weber of the architectural firm D.H. Burnham and Company, which opened in 1897. The building's architecture reflects the transition from Romanesque Revival architecture to Chicago school architecture. The Silversmith Building was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1997 and became a member of the National Register of Historic Places in 2016.

1900

sidebar

At the turn of the century, restaurants began to group together in Chicago's Loop (downtown). The reason is not hard to understand. Groups of the same kind of restaurants, i.e., Cafeterias, attracted flocks of lunch customers who knew they were likely to find something they wanted to eat and get quick lunch-time service.

Chain restaurants were becoming more common, and lesser-known restaurants were eager to locate near the successful eating establishments to catch their overflow. It was also used as a marketing tool. City officials nicknamed streets of similar-style restaurants as a "row" to help boost the local economy.

- Restaurant Row: Randolph Street, where there were 39 busy, full-service restaurants within a six-block stretch.

- Cafeteria Row: Wabash Avenue had the largest number of self-service restaurants in the world.

- Toothpick Row: Clark Street had lots of lunchroom businesses.

My Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal; Restaurants & Foods

1906

The New Hotel Brevoort was owned by Hannah & Hogg. It was a 14-story building located at 120 West Madison Street, between Clark and LaSalle Streets. Billed as "Absolutely Fireproof" when it opened in 1906.

The entrance featured a decorative vaulted ceiling, hanging glass-paned light fixtures, and a circular window over the front entryway.

The Lobby of the Hotel Brevoort was highlighted by a second-floor mezzanine level with a beautifully curved railing. The decor featured maroon marble around fluted white and gold square columns, as well as decorative tile floors. A stairway leads up to the mezzanine level. Heavy leather chairs and dark green furniture, accented with maroon velvet, were arranged around a maroon Oriental rug. The ceiling was painted in deep blues and purples.

The Hotel Brevoort Buffet had one of the most ornate bars in Chicago. This unique round bar, featuring a glass rail and mirrored columns, was decorated with elaborate tile patterns and a plaster rotunda. A chandelier and circular shelves hung in the middle. Deep maroons, cream, rose, green, and gold colors created an elegant look.

The Hotel Brevoort enhanced its ornate interior with the addition of the Rainbow Room Dining Room, featuring large wall-size murals. A stairway leads down to the Rainbow Room Restaurant. The colorful wall murals depicted "Hindu Pilgrims Preparing the Evening Meal on the Banks of the Ganges." The dining area featured tile floors and maroon marble walls following the Lobby and Bar style. A novel for its time, the room was cooled with electric fans perched above a room divider.

The building's original facade was clad in glass and converted into an office building in 1953.

Today, the building is a steel and glass, 30-story tower with a Republic Bank in its lobby.

|

| The New Hotel Brevoort, 120 W. Madison Street, was billed as "Absolutely Fireproof." |

1926

The Palmer House IV, S.E. corner State and Monroe Streets, 1926.

Concluding the Palmer House saga.

Although the third Palmer House Hotel had been carefully maintained and remained profitable throughout its existence. By 1919, it was clear to the Palmer Estate that Chicago could support a much larger hotel.

The construction of the new Palmer House Hotel took place in stages, allowing the hotel business to continue operating in the old building. The first stage built was the eastern portion of the new building, east of the existing hotel building along Monroe and Wabash.

Then, after this new section was open to business, the old Hotel was razed to construct the rest of the new structure. The new building, 25 stories, was completed in 1927. In 1945, Conrad Hilton purchased the Palmer House and continues to own it today.

Copyright © 2022 Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D. All rights reserved.