In historical writing and analysis, PRESENTISM introduces present-day ideas and perspectives into depictions or interpretations of the past. Presentism is a form of cultural bias that creates a distorted understanding of the subject matter. Reading modern notions of morality into the past is committing the error of presentism. Historical accounts are written by people and can be slanted, so I try my hardest to present fact-based and well-researched articles.

Facts don't require one's approval or acceptance.

I present [PG-13] articles without regard to race, color, political party, or religious beliefs, including Atheism, national origin, citizenship status, gender, LGBTQ+ status, disability, military status, or educational level. What I present are facts — NOT Alternative Facts — about the subject. You won't find articles or readers' comments that spread rumors, lies, hateful statements, and people instigating arguments or fights.

FOR HISTORICAL CLARITY

The transparent gesture placated no one, and the Cleveland Gazette charged that she was only "a sort of general utility clerk" whose real task was "to get Negroes in line." Within a few months, she resigned, her brief stay only emphasizing that Negroes were excluded from prestigious, policy-making positions.

When I write about the INDIGENOUS PEOPLE, I follow this historical terminology:

- The use of old commonly used terms, disrespectful today, i.e., REDMAN or REDMEN, SAVAGES, and HALF-BREED are explained in this article.

Writing about AFRICAN-AMERICAN history, I follow these race terms:

- "NEGRO" was the term used until the mid-1960s.

- "BLACK" started being used in the mid-1960s.

- "AFRICAN-AMERICAN" [Afro-American] began usage in the late 1980s.

— PLEASE PRACTICE HISTORICISM —

THE INTERPRETATION OF THE PAST IN ITS OWN CONTEXT.

The World's Columbian Exposition held in Chicago in 1893 symbolized the ascendancy of the United States among the world powers. It reflected the self-confidence and optimism of America in an age in which its citizens believed to be the most advanced in history. Negroes, only one generation removed from slavery, viewed the Exposition enthusiastically as a showcase for Negro achievement. In practice, however, they found themselves excluded from prestigious positions on the Exposition Commission, almost completely barred from all but menial employment, and practically unrepresented in the exhibits.

Because all its buildings had white exteriors, the fair was nicknamed "The White City," but Negro visitors dubbed it "the great American white elephant," or "the white American's World's Fair." Negroes sharply disagreed among themselves concerning the most effective methods of dealing with the discrimination they encountered, but they agreed in their disappointment and disillusionment.

The Exposition received official recognition from the United States government and was financed partly by Congressional appropriations. In 1890, President Benjamin Harrison (1889-1893) appointed a large national commission representing all the states and territories to supervise plans for the celebration. Negroes were hurt when they learned that the entire commission was "simon-pure (absolutely genuine) and lily-white (a person or organization that rejects any culture other than white Americans)'' and charged that a Negro commissioner was unthinkable to the President because the appointment "would savor too much of sentimentality, and be ... distasteful to the majority of the commissioners themselves."

Leaders in the National Convention of Colored Men and the Negro Press Association urged the President to add a Negro to the Commission. The humiliation of being ignored by the White House was almost equaled by the embarrassment of begging for what Negroes regarded as their right to representation. In March 1891, Harrison assured one delegation of Negroes that he was sympathetic but that there were simply no vacancies on the Commission. However, he named Hale G. Parker, a St. Louis school principal, as an alternate commissioner shortly afterward. Negroes might not have protested if this token appointment had been made initially. Still, when the selection was announced, Harrison was criticized because Parker's duties were of a "nonactive character."

Furthermore, the President was held at least partly responsible for the absence of Negroes from the Exposition's Board of Lady Managers,' headed by Mrs. Potter Palmer, a Chicago socialite originally from Kentucky. This board contained nine Chicagoans and two members and two alternates from each state and territory. The board members ignored requests by Negroes for representation and appointed a white woman from Kentucky "to represent the colored people." The Lady Managers pointed to dissension among various Chicago "factions of Negroes," each one clamoring for recognition to justify this action. The Negro factions were indeed feuding with each other, and the Lady Managers circulated the document widely with the following patronizing passage:

The Board of Lady Managers would most earnestly urge the leaders of the various factions to sacrifice all ambition for personal advancement and work together for the good of the whole, thus seizing this great opportunity to show the world what marvelous growth and advancement have been made by the colored race and what a magnificent future is before them.

Negroes realized that they had received an intended slight from the aristocratic Mrs. Palmer.

As late as the end of 1891, the colored women of Chicago were still fighting with each other. The appointment of a Negro, Mrs. Fannie Barrier Williams, prominent club woman, civic worker, and wife of the lawyer S. Laing Williams, to the Fair's Bureau of Publicity, was allegedly dropped because several other Negroes considered her objectionable. The Freeman considered the feuding in Chicago as all too typical of race behavior in many cities: "It is a hellish, disgraceful and lamentable characteristic of the Negro race, to be the first to pull down their own ... because of jealousy and envy. ... Talk about race pride, there is no such thing."

On December 30, 1892, Exposition officials announced the appointment of a Negro, Mrs. A. M. Curtis, wife of a prominent physician, as Secretary of Colored Interests. Mrs. Curtis was supposed to see that exhibits by Negroes received fair play, but a Chicago daily newspaper pointed out that although her desk was in Mrs. Palmer's office, she had no real power.

|

| Chicago Tribune, Saturday, December 31, 1892. |

Frederick Douglass and the noted anti-lynching crusader, Ida B. Wells, decided that visitors to the Fair should know that Negroes were "studiously kept out of representation in any official capacity and given menial places." Through the Negro press, they asked the Negro public to contribute five thousand dollars toward printing the booklet, "The Reason Why The Colored American Is Not In The World's Columbian Exposition" (pdf). Since the document was intended primarily for foreign visitors, the authors proposed to distribute the booklet, without charge, in English, French, German, and Spanish editions.

This suggestion was condemned scathingly by many Negro editors. The Methodist Union denied the existence of discrimination. It held that no other ethnic minorities in the United States would print such a booklet, which was "calculated to make Negroes the butt of ridicule in the eyes... of the world. We are," the Methodist Union insisted, "going to Chicago as American citizens," not "as an odd race." The accommodating Indianapolis Freeman argued that although Negroes suffered from racial discrimination, they demeaned themselves by publicly admitting it to foreign visitors. The editor cautioned that foreigners could not ameliorate (make something bad better) the conditions under which Negroes were forced to live. Those complaints about mistreatment would increase white hostility in the United States. The Douglass-Wells booklet was also condemned because Negroes should conserve wealth instead of wasting it. One journal held that $5,000 could be spent more wisely by establishing a national orphan asylum. Another objected to a public solicitation because the collection of nickels and dimes from washerwomen furnished ammunition to believers in the "infantile mental and financial capacity of Negroes."

The Cleveland Gazette, Afro-American Advocate, Coffeyville, Kansas (1891-1893); Philadelphia Tribune; Richmond Planet; and Topeka Call were among the newspapers supporting Douglass and Miss Wells. They held that every Negro should lend financial support to the venture because the entire race would benefit from the broadest possible distribution of the booklet. The Topeka Call especially condemned the jealousy of those editors who were "pouring hot shot" on Douglass. In mid-1893, four months after the Douglass-Wells appeal to the Negro press for funds, the contributions received were described by Miss Wells as "very few and far between." Since only a few hundred dollars had been collected, the authors limited themselves to an edition in English.

Not only was there a lack of Negro representation on the honorary committees, but there was also discrimination in employment. Aside from porters, the Negro staff included only an Army chaplain detailed from the War Department, a nurse, two messengers, and three or four clerks. One of these "under clerks" worked in the Bureau of Publicity as the representative of the Negro press. The Chicago Conservator and the Indianapolis Freeman complained that the post should have been given to an editor of a Negro weekly, but "the assignment of any colored man of national reputation to any work in the World's Fair management is apparently against the policy of the powers that be."

It is doubtful whether Negro visitors experienced discrimination at the restaurants and amusements on the Exposition grounds. In a survey of several Negro newspapers, the writers found only one instance of racial exclusion at the Fair. In August 1893, the Indianapolis Freeman reported that a Negro woman from Lexington was refused entertainment in the Kentucky Building at the Fair. Perhaps the buildings of other Southern states also discriminated against Negro visitors, but in the Negro press, there were no references to such treatment. However, there were accounts of Negroes having dined in the California building and the Bureau of Public Comfort. If racial discrimination had been pervasive, almost certainly, that fact would have been mentioned by Negroes visiting Chicago for meetings of the Colored Men's Protective Association and other organizations. The Chicago press reported complaints by Negroes against the Exposition management, but discrimination in public accommodations was not among the grievances.

|

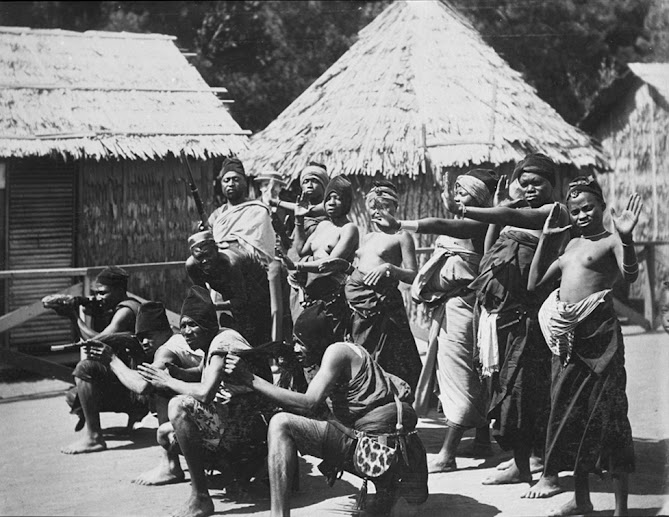

| The Chicago Times newspaper (1854 until 1895 when it merged with the Chicago Herald), publisher of the picture book "Portfolio of the Midway Types," said of the Dahomey Village: “Its inhabitants were just the sort of people the managers of the Exposition did not attend banquet or surfeit (an excessive amount) with receptions.” |

An important issue on which Negroes divided sharply related to the nature and character of the participation by Negroes in the exhibits. Basically, Negroes wanted representation without discrimination, but when discrimination became apparent many urged that a separate area for exhibits by Negroes would be desirable. The New York Age noted that few Negroes would have pressed for a Negro Annex if they had not been ignored so consistently by the Exposition officials. Many Negroes opposed any type of segregation, and late in 1890, a Chicago mass meeting adopted a resolution presented by Ferdinand L. Barnett, a prominent lawyer and one of the founders of the Conservator, urging those Exposition officials to make a special effort to encourage exhibits by Negroes and to display them in appropriate departments throughout the Fair. On the other hand, desiring to ensure participation by Negroes and to allow them to demonstrate advancement, J.C. Price, the president of Livingstone College and of the Afro-American League and, at the time, one of the half-dozen leading Negroes in the country, suggested that the Exposition should feature a Negro Annex or Negro department. Another Negro criticized any Negro who was "willing to dump his handiwork into a promiscuous heap with all nations and still expect identical credit. ... If we possess genius, our white brother assumes that the fact has not been established to his satisfaction . ... Under this condition can we afford to forego any and all legitimate means to make a place for ourselves?"

Pressed by both sides, the board of managers listened to neither. In the spring of 1891, it ruled against racially separate exhibits. Still, instead of making a special effort to encourage Negroes to exhibit throughout the Fair, they told them to submit their displays to screening committees established in the various states. Since the great majority of Negroes lived in the South, it was evident that they could expect little attention to their interests at best. Yet Negroes attempted to follo\v the advice of Fair officials. Several newspapers urged the formation of local industrial associations to awaken interest in producing exhibits; readers were advised to forget past insults and prove to the world that they were not a passive, dependent, and uncreative people. However, few such organizations were set up, although the Negro World Columbian Association asked to be notified of "all handiwork or creditable evidence" that could be displayed suitably in Chicago. The Columbian Association and other groups petitioned Congress for a collection and compilation of statistics demonstrating the progress of Negroes since Emancipation to be displayed as part of the United States government exhibit at the Fair. Still, the legislators in Washington refused to pass the bill.

Hale Parker, the Negro appointed alternate Commissioner, initially endorsed the managers' decision on the exhibits and regarded a Negro Annex as "offensive and defensive" and held that "We wish ... to be measured by the universal yardstick and if we fall short the world knows why. But for one, I do not fear the test, and those who have ... made a careful observation of the material progress of the colored people have no reason to fear an eclipse in the glory and grandeur of the fair." Later, however, candidly admitting his inability to influence Exposition officials, he conceded that exhibits by Negroes "in many instances, would have to be submitted to the judgment of their enemies in States of the Union not likely to court or encourage the "social equality" of exhibits and the commercial brotherhood of their producers." Nevertheless, fearing that discrimination by the Exposition managers would cause some potential Negro exhibitors to boycott the Exposition as an "unclean thing," Parker condemned false racial pride. "Nothing short of prohibition from the fairgrounds could operate as a valid reason for not exhibiting," he insisted.

The Fair opened on May 1, 1893. Negro visitors expressed disappointment at the scarcity of exhibits by Negroes. One of them wrote: "There is a lump which comes up in my throat as I pass around through all this ... and see but little to represent us here." However, they took pride in the Haitian and Liberian pavilions. They noticed that several Negroes from New York and Philadelphia displayed needlework and drawings in the Women's Building. Booths represented Wilberforce University, Tennessee Central College (now defunct), Atlanta University, and Hampton Institute in other parts of the Exposition.

Less edifying was a sideshow on the Midway, consisting of a Dahomey Village. Negro leaders did not approve of the Midway activities involving Africans from Dahomey, and the Dahomians objected to questions about their past cannibalism.

Frederick Douglass contemptuously commented that the Exposition managers evidently wanted Negro Americans to be represented by the "barbaric rites" of "African savages brought here to act the monkey."

Racism seems to have been planned in advance by the fair's board of directors.

On the Midway Plaisance, a mile long and 600 feet wide strip of land, visitors encountered a lesson in “race science” and social Darwinism. Here they saw “living exhibits”— representatives of the world’s “races,” including Africans, Asians, and American Indians. The two German and two Irish villages were located nearest to the White City. The farther west you went were villages representing the Middle East, West Asia, and East Asia. So, the closer one got to the Midway exit gate at the west end of the Midway, visitors were descend to the savage races, the African of Dahomey (with a history of cannibalism) and the North American Indians, each of which has its place at the far end of the Plaisance. Fear was so prevalent that the fair management posted a placard just outside the entrance to the Dahomey village. It was a request to all visitors that they refrain from questioning the natives of the village regarding their past cannibal habits of themselves and their ancestors, as it was very annoying to them.Undoubtedly, the best way of looking at these races was to behold them in the ascending scale, starting at the west entrance gate, moving eastward toward the 'White City" main fair, starting with the lowest specimens of humanity, reaching continually upward to the highest stage with the thought of evolution, until you arrived at the fair proper.The fair’s organizers promoted the idea that the “savage races” were dangerous by warning that the Dahomey women are as fierce if not fiercer than the men, and all of them have to be watched day and night for fear they may use their spears for other purposes than a barbaric embellishment of their dances. The stern warning reinforced many Americans’ fears that negroes could not be trusted and were naturally predisposed to immoral and criminal behavior and thus kept away from white people through segregation.

If the proposal for a Negro Annex aroused controversy among negroes, a veritable furor arose when the Exposition managers announced a Colored Jubilee Day on August 25, 1893. To many Negroes, already infuriated by discrimination at the Exposition, the idea of a "Negro Day" was intolerable. On this issue, even Frederick Douglass and Ida Wells were in disagreement.

The celebration was originally suggested by several Negroes on the East Coast who proposed that a day be set aside for folk music, speeches, and general thanksgiving. Exposition officials agreed, having already scheduled similar celebrations for Swedish, German, Irish, and other nationalities. Douglass lauded this opportunity to display Negro culture and "the real position" of Negroes. However, Miss Wells declared that the celebration was a mockery intended to patronize them. She accused Exposition officials of seeking to entice lower-class Negroes by providing two thousand watermelons. The degrading vision she presented was quite different from Douglass' portrait:

The sell-respect of the race is sold for a mess of pottage and the spectacle of the class of our people who will come on that excursion roaming around the grounds munching watermelon will do more to lower the race in the estimation of the world than anything else. The sight of the horde that would be attracted there by the dazzling prospect of plenty of free watermelons to eat, will give our enemies all the illustration they wish as an excuse for not treating the negroes with the equality of other citizens.

Miss Wells received plenty of newspaper support. The Cleveland Gazette advised self-respecting Negroes to ignore the Exposition since the only privilege they received was to spend money there. The Topeka Call approvingly published a memorial written by a group of Negroes in Chicago, who insisted that since "there is to be no 'white American citizen's day,' why should there be a 'colored American citizen's day'?"

As the celebration approached, prominent Negroes such as the former Congressman J . Mercer Langston and the famous singer Sisserietta Jones (the "Black Patti") refused to participate. The Colored Men's Protective Association, which held its national meetings in Chicago, would not endorse the program. A group of Chicago ministers planned suburban excursions to discourage attendance by Negroes.

Douglass, who insisted that Negro Day (aka Colored People's Day) was a small but valuable concession extracted from racist Fair officials, was annoyed by the "petulance" of the editors and in a lecture to them, claimed that "all we have ever received has come to us in small concessions and it is not the part of wisdom to despise the day of small things." The Negro promoters of the celebration tried to ensure a large audience by working through Negro fraternal organizations. Obviously, the sponsors were on the defensive because they assured Negroes that Colored People's Day would not be an occasion of discredit or ridicule and pleaded with them to come and show whites how "refined, dignified, and cultured" Negroes really were.

Contemporary accounts in the Negro press differ on the degree to which the celebration was a success. The Indianapolis Freeman reported that less than a thousand Negroes showed up, while the Topeka Call estimated several thousand entered the Exposition grounds. Besides Douglass, notables on the platform included Bishops Henry M. Turner of the African Methodist Episcopal Church and Alexander Walters of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church. The rising young poet, Paul Laurence Dunbar, recited his poem, "The Colored American." Musical selections were presented by the concert singers Harry T. Burleigh and Madame Delseria Plato. Even the Freeman, which recorded the occasion as a "dismal failure," agreed that the musical portion of the program was "a glittering success."

Douglass, giving the main address of the day, used the occasion not to praise the Fair but to vindicate the progress made by Negro Americans despite conditions of persecution and injustice and to denounce the policies of the fair managers. He denied "with scorn and indignation the allegation ... that our small participation in this World's Columbian Exposition is due either to our ignorance or to our want of public spirit." That Negroes were "outside of the World's Fair is only consistent with the fact that we are excluded from every respectable calling." He excoriated Northern whites for catering to their former enemies in the white South were cheating, whipping, and killing Negroes were everyday occurrences while at the same time discriminating against Negroes, who were their friends. "In your fawning upon these cruel slayers, you slap us in the face. With the same shallow prejudice which keeps us in the lowering rank in your estimation, this exposition denied mere recognition to eight million and one-tenth of its own people. Kentucky and the rest object, and thus you see not a colored face in a single worthy place on these grounds. ... Why in Heaven's name," he exclaimed, "do you take to your breast the serpent that once stung, and crush down the race that grasped the saber and helped make the nation one and therefore the exposition possible?"

Ida Wells was so impressed when she read the reports of this speech in the newspapers that she immediately apologized to the distinguished elder statesman. Douglass' speech had articulated brilliantly Negro alienation and disillusionment with the actions of Northern whites in general and with the fair in particular. In fact, he made it crystal clear that for Negroes the fair symbolized not the material progress of America but a moral regression — the reconciliation of the North and South at the expense of Negroes.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Thank you! I was just invited to join the Facebook group, Friends of the White City and was reluctant until I came across a link to this article. I wrote the pictorial history book "African Americans in Chicago" and am now working on publishing my own follow up to it, "AfAm Album". I'd like to use some of your info and photos here. Please let me know how I can meet and discuss it with you.

ReplyDeleteVery valuable collection. Truly appreciate that you have not shied away from the documentation of racist attitudes and actions by fair organizers or the tense struggles within the black community to address these behaviors. Well done.

ReplyDelete