The narrative of The Illinois, aka Illiniwek or Illini, unfolds like a saga, etched against the backdrop of the Illinois country. Once a thriving confederacy, they rose to prominence, endured hardship, and ultimately witnessed the decline of their civilization. This interwoven account incorporates various threads, traversing from their early encounters with Europeans to the internal dynamics of Illiniwek society, with a particular focus on women's crucial role.

sidebar

The Illinois is pronounced as plural: [The Illinois'] was a Confederacy of Indian Tribes consisting of the Kaskaskia, Cahokia, Peoria, Tamarais (Tamaroa, Tamarois), Moingwena, Mitchagamie (Michigamea), Chepoussa, Chinkoa, Coiracoentanon, Espeminkia, Maroa, and Tapouara tribes that were of the Algonquin family. They spoke Iroquoian languages. The Illinois called themselves "Ireniouaki" (the French word was Ilinwe). All the tribes seemed to work together without issue.

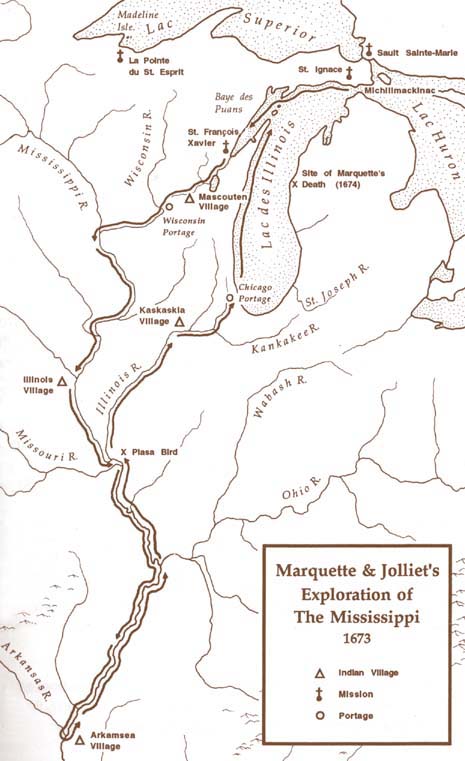

Our story commences with the Grand Village of La Vantum, a bustling metropolis teeming with 6,000 Illiniwek inhabitants. Nestled strategically along the Illinois River, this community thrived. The French explorers Marquette and Jolliet emerged as the first Europeans to set foot in La Vantum in 1673. Chief Chassagoac welcomed the newcomers warmly, exemplifying the Illiniwek's peaceful nature. This initial contact began a complex relationship between the Illiniwek and the Europeans, ultimately reshaping their history.

Before European arrival, the Illiniwek Confederacy, a powerful alliance of Algonquian-speaking tribes, dominated the region. However, the arrival of French missionaries and fur traders in the 17th century ushered in a period of immense change. The Illiniwek, unfortunately, bore the brunt of these transformations. Warfare and the introduction of diseases by the Europeans wreaked havoc on their communities. By the 1830s, a once-mighty confederacy had been reduced to a single village, their ancestral lands ceded to appease European encroachment. The Peoria Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma stands today as the sole remnant of this formidable people.

However, a closer look at the Illiniwek's history in the late 17th century reveals a more nuanced narrative than one of mere decline. Recent scholarship challenges the portrayal of the Illiniwek as a weak and passive people as depicted in early French accounts. Instead, evidence suggests they were a formidable force, strategically leveraging bison hunting and the slave trade to bolster their power. This revisionist perspective underscores the importance of decentering European narratives and foregrounding the agency of Indian groups in shaping their destinies.

A pivotal event that tragically altered the course of Illiniwek history unfolded in the village of La Vantum in 1680. A brutal massacre orchestrated by the Iroquois tribe left an indelible scar on the Illiniwek people. The Iroquois, harboring animosity towards the Illiniwek, descended upon La Vantum, unleashing a torrent of violence. French explorer Tonti, residing in the village alongside a contingent of priests and soldiers, became embroiled in the conflict. The Iroquois, mistaking the French for Illiniwek allies, subjected Tonti to torture. The massacre also claimed the lives of two priests, Fathers Gabriel and Zenobe. Countless Illiniwek people perished in the onslaught, while the survivors were forced to flee, forever displaced from their homeland.

To fully comprehend the Illiniwek Confederacy, we must delve into its foundation – the constituent tribes. The Peoria, Kaskaskia, and Cahokia were just a few prominent groups that united under the banner of the Illiniwek. Interestingly, the name "Illiniwek," signifying "the men," originated from their own designation. Upon encountering this powerful alliance, French explorers bestowed upon them the name Illinois, a moniker that has endured. The arrival of Marquette and Jolliet in 1673, the voyage etched a path down the Mississippi River, marked a significant chapter in the annals of European-Illiniwek interaction.

The narrative is complete by acknowledging women's critical role in Illiniwek society. While Illiniwek women were not traditionally involved in hunting or warfare, their contributions were essential. They shouldered the responsibility of gathering food, nurturing children, and managing the domestic sphere. Their influence extended beyond the household, as some women served as shamans and actively participated in specific ceremonies. Marriages within Illiniwek society adhered to a gift-giving system, and women possessed the remarkable right to divorce their husbands. Although societal norms placed men in a position of higher authority, Illiniwek women wielded considerable power within their designated domain.

The Illiniwek saga, a tapestry woven with threads of triumph and tribulation, stands as a testament to the enduring human spirit. From their initial encounters with Europeans to the internal dynamics of their society, their story offers valuable insights into a bygone era. By delving into the complexities of their history, we gain a deeper appreciation for the Illiniwek people and the indelible mark they left on the landscape of North America.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.