— PLEASE PRACTICE HISTORICISM —

THE INTERPRETATION OF THE PAST IN ITS OWN CONTEXT.

|

| Lincoln's Inauguration, March 4, 1861. |

The word democracy occurs only 137 times in the collected writings of Abraham Lincoln. But no other word described what he saw as the most natural, the most just, and the most progressive form of human government in existence. Nothing, he said, could be “as clearly true as the truth of democracy.”

Of course, being “clearly true” (or, as Thomas Jefferson might have put it, self-evident) did not mean that everyone applauded it or assented to it in Lincoln’s lifetime. Democracy had a long history, and not all of it was admirable. Classical Athens may be said to have been the pilot program for democracy, beginning in the sixth century B.C., when the ordinary citizens of Athens saved their city from occupation by the forces of Sparta and lodged political power in the hands of the city Assembly. But many of the shrewdest of Athenian thinkers — Thucydides the historian, Plato, the Philosopher — were skeptical about turning over control of the city to what often behaved like a mob. Plato never allowed Athenians to be forgiven for executing his teacher, Socrates. He was convinced that most people have “no knowledge of true being, and have no clear patterns in their minds of justice, beauty and truth.”

The French Revolution did not give democracy a better reputation, especially after it descended into the Reign of Terror and revealed what Ruth Scurr has called “the uneasy coincidence of democracy and fanaticism.” The restored European monarchies of Lincoln’s day, having learned the hard lesson of the guillotine, had scant use for democracy, and even the least monarchical of all the monarchies — that of Great Britain — was nevertheless governed by a deeply-entrenched aristocracy whose members would continue to constitute a majority of every ministerial cabinet until 1906.

Nevertheless, for Lincoln, democracy was what Hans Kelsen called “a generally recognized value,” and his loyalty to democracy was what armed him to combat the spread of human slavery in the United States. Even though democracy is a political system and slavery an economic system, Lincoln believed that they were in death’s grip with each other. “As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master,” he wrote in 1858, “This expresses my idea of democracy. Whatever differs from this to the extent of the difference is no democracy.” So, when the thunderous cloud of Civil War broke over his presidency, Lincoln had no hesitation in portraying the struggle as a contest, not over constitutional niceties or even over slavery itself, but over the basic principle of democracy.

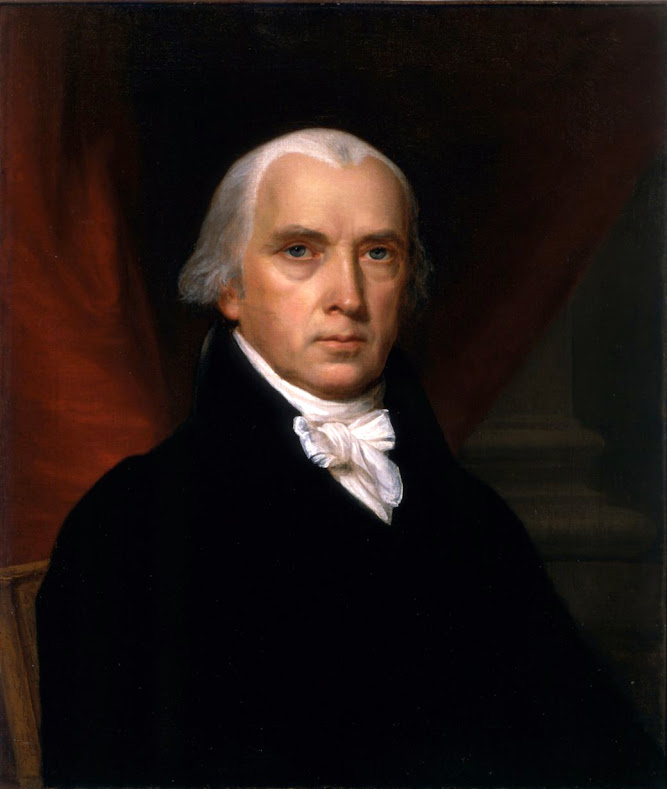

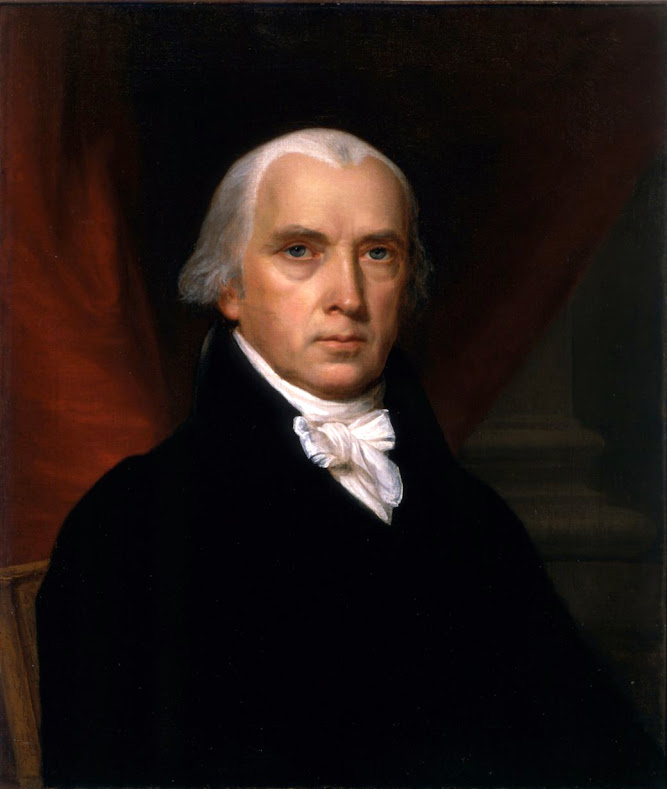

The fundamental notion of any democracy is that political sovereignty resides in the people; strictly speaking, this differs from a republic, where sovereignty also is understood to rest, ultimately, in the hands of the people, but which is deployed through their representatives. “A pure democracy,” wrote James Madison in the tenth of the Federalist Papers, can only be “a society consisting of a small number of persons, who assemble and administer the government in person.” A republic is “a government in which the scheme of representation takes place” and involves “the delegation of the government to a small number of citizens elected by the rest.” Madison understood this “delegation” as a kind of purifying process “to refine and enlarge the public views, bypassing them through the medium of a chosen body of citizens, whose wisdom may best discern the true interest of their country.” In other words, republics mistrust democracy, or at least the run-of-the-mill of the people who compose democracies. Republics envision a role for a more elevated elite, who can do for the people what the people ought to do, but often don’t.

|

| James Madison |

The American founders understood themselves as creating a republic. Even the most rousing of the Revolutionary rabble-rousers, Tom Paine, never even uses the term democracy in his famous broadside against the monarchy, Common Sense, in 1776. Yet, it was clear during the Revolution that the line between a democracy and a republic was a porous one. In 1777, Alexander Hamilton praised the new revolutionary constitution of New York as a “representative democracy” (thus mingling the two concepts) because “the right of election is well secured and regulated, and the exercise of the legislature, executive and judiciary authorities, is vested in select persons,” but persons “chosen really and not nominally by the people.” Half a century later, republicanism and democracy had fused: the 1787 Constitution had created a system of delegated representation that captured perfectly the ideal of a republic, but no class of natural elites emerged whom the mass of the people would obligingly vote as their representatives.

And no wonder the freedom Americans enjoyed from entanglement in European wars eliminated any possibility of the formation of a professional military elite, and the prevalence of evangelical Protestant religion undermined any notions of social hierarchy.

|

| Alexis de Tocqueville |

By the time Alexis de Tocqueville arrived in America to begin his analysis of American political society, republican was still the noun, but democratic had become the adjective, and the adjective so controlled the noun that it only made sense for Tocqueville to entitle his inquiry, Democracy in America — Democracy, and not Republicanism. “A democratic republic subsists in the United States,” Tocqueville wrote: the country’s sheer size and the preference Americans had for commerce rather than politics made an indirect system of representation desirable, but the internal spirit of that system would be highly democratic because the American people have “a taste for freedom and the art of being free,” and don’t need to have their views refined and enlarged by others. It is those tastes — Tocqueville called them mores – that make what was designed as a republic work as a democracy in a “more or less regulated and prosperous” fashion.

So, when Lincoln spoke of democracy, he was speaking of a republican system in which democratic habits had become so pervasive that they reversed the usual flow of republicanism. Instead of the representatives restraining the wildness of the people, the people themselves set the limits of what those representatives may do. “By the frame of the government under which we live, these same people have wisely given their public servants but little power for mischief,” Lincoln explained, “and have, with equal wisdom, provided for the return of that little to their own hands at very short intervals.” Under the canopy of democracy, the people are judged competent to direct their own lives, public and private, without needing or wanting the paternal tyranny of aristocrats and monarchs or the meddlesome oversight of the wealthy or the learned. “The legitimate object of government,” Lincoln wrote in 1854, “is to do for a community of people, whatever they need to have done, but cannot do, at all, or can not, so well do, for themselves in their separate, and individual capacities. In all that the people can individually do as well for themselves, the government ought not to interfere.” The purpose of government, Lincoln said, was not to organize, stratify or mobilize the people, but simply to level the playing field, in order to guarantee “an unfettered start, and a fair chance, in the race of life” by securing equality before the laws. Thus government’s principal utility was to maximize personal transformation, “to lift artificial weights from all shoulders” and “to clear the paths of laudable pursuit for all.”

In such a “community” — such a democratized republic — two rules must be obeyed as with iron rods:

1. The rule of the majority.

Whatever principles and policies are endorsed by the majority of that people must become the principles and policies of their government; otherwise, the sovereignty of ‘the people’ means nothing. “If the majority does not control, the minority, would that be right?” Lincoln asked. “Would that be just or generous? Assuredly not!” By the same measure, the minority who have disagreed must acquiesce in the majority’s rule. “If the minority will not acquiesce,” Lincoln concluded, “the majority must, or the government must cease.” What was worse, an unbowed minority would “make a precedent” for themselves “which, in turn, will divide and ruin them; for a minority of their own will secede from them” whenever disagreement breaks out. The long-term result — and truth be told, it will not be a very long term — will be either “anarchy or...despotism.” Sovereignty will either evaporate as each separate faction or individual does what is right in their own eyes; or else, in desperation, decent men will turn to a dictator to sort out the chaos. “The rule of a minority, as a permanent arrangement, is wholly inadmissible,” Lincoln said, “so that, rejecting the majority principle, anarchy, or despotism in some form, is all that is left.” That was why the Civil War was what Lincoln called “essentially a People’s contest.” The Confederate rebellion was an assault by a minority on the decision of the majority, as expressed in Lincoln’s own election, and in that way, it was really intended to question the entire principle of democracy.

2. The legitimacy of the minority.

No majority is perfect or infallible simply for being a majority. In a democracy, the rule of self-interest, persuasion, reason and civility guarantee that a minority may cling to its opinion, and use every legitimate opportunity to convince others that they are right. “We should remember,” Lincoln cautioned his own allies once he became president, that “while we exercise our opinion... others have also rights to the exercise of their opinions, and we should endeavor to allow these rights, and act in such a manner as to create no bad feeling.” It is the mark of the dictator, not a democracy, to treat the minority as a social enemy, to be put up against the barn wall and shot, or (in the case of the Confederate rebellion) to engage in a “deliberate pressing out of view, the rights of men, and the authority of the people.” There was, in Lincoln’s ‘idea of democracy,’ no need for firing squads to conclude arguments. “I do not deny the possibility that the people may err in an election,” Lincoln admitted in 1861, “but if they do, the true cure is in the next election.”

To set aside those rules, whether out of weakness or confusion, was to cast doubt on whether democracy really had any legitimacy whatsoever. The challenge of the Confederate rebellion was not directed solely at him or his party or his administration; it presented “to the whole family of man, the question, whether a constitutional republic, or a democracy, a government of the people, by the same people can, or cannot” survive the push-and-shove of its own people’s disagreements, or whether democracies are doomed forever to fly off, by their own centrifugal force, into fragments. “For my part,” he told his secretary, John Hay, in May 1861,

I consider the central idea pervading this struggle is the necessity that is upon us of proving that popular government is not an absurdity. We must settle this question now, whether in a free government the minority have the right to break up the government whenever they choose. If we fail, it will go far to prove the incapability of the people to govern themselves.

Or, as he would put it more eloquently at Gettysburg in November 1863, the war was “testing whether this nation or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure.”

If those two rules are the basic operating system of democracy, then we should also notice that these two rules also require rules of their own to operate rightly. First, democracy operates best within the boundaries of a nation-state. This is not a concept that, in an increasingly globalized world economy, meets with much enthusiasm today. However, the nation-state actually provides the only effective means of identifying who belongs to a certain democratic entity (which is to say, its citizens) and who is an interloper not subject to its restraints and who could harm it with impunity. Second, within that nation-state, there should be a reasonably broad franchise — in other words, almost all adults within its boundaries should be entitled to vote and to hold office. Third, voting should be without coercion or manipulation. Fourth, citizens may organize themselves into political associations of their own choosing. And fifth, political information is permitted to circulate freely and without hindrance among the citizens.

Having laid down these five secondary rules, it will not take much insight to see that the Confederacy formed as much a threat to these secondary rules as it did to the two operating rules. To begin with: the Confederacy did not exhibit “a reasonably broad franchise” and had not for years, even for its white population. In the eleven states which would form the Confederacy, only one (Tennessee) showed voter participation higher than the national average in the 1852 presidential election; the rest showed voter participation 15% lower, and in some cases lower by 20% than in the free states. A pro-secession propagandist like Edmund Ruffin frankly despised his own Virginia legislature as “that despicable assembly” because of “the enlargement of the constituency to universal suffrage.”

Likewise, the Confederacy did not permit full and free discussion of political issues because its political life was marked by nothing so much as the suppression of free speech and the control of the circulation of free political information. In 1835, the postmaster-general, Amos Kendall, refused to protect the distribution of anti-slavery materials through Southern post offices in terms eerily reminiscent of ‘cancel culture,’ because (Kendall said) “we owe an obligation to the laws, but a higher one to the communities in which we live,” and those communities demanded censorship to save them from offenses.

In truth, the Confederacy had lost all grip on democracy and had become an oligarchy, managed by a handful of slave-owning elites. “Society is a pyramid,” explained the editor of the Nashville Daily Gazette late in 1860. “We may sympathize with the stones at the bottom of the pyramid of Cheops, but we know that some stones have to be at the bottom and that they must be permanent in their place.” The stones, in this case, were slaves. No wonder James Madison feared slavery as the oligarchic snake in the republican garden since the classical republics whose vices he had studied had demonstrated all too well that “in proportion as slavery prevails in a State, the Government, however, democratic in name, must be aristocratic in fact.” At every point, the Confederacy had failed the democratic test.

Yet, the Confederacy is also a chilling example, for us as much as for Lincoln, of how easily a democratic republic can slide backward into coercion and hierarchy. The realization that haunted Lincoln was that democracies tend to be, as Thomas Hobbes’s definition of life, 'nasty, poor, mean, brutish, and short.'

Especially short. Most human societies had maintained order by either coercion or superstition. The few who had not done so sooner or later succumbed to the fear of anarchy and welcomed the Alexanders and the Caesars to create order. At the very beginning of his political career, Lincoln had feared this was about to overtake the American democracy. In his first major political speech, the Lyceum Address of January 1838, Lincoln was convinced that Americans were in real danger of political self-destruction since the tsunami of mob actions in the previous year looked so destabilizing that Americans might be tempted to look to some “Towering genius” who “thirsts and burns for distinction” to save them from “a Government that offers them no protection.”

Once installed, people tolerated the rule of Alexander and Caesar, not only because they promised law and order, but because (and this Lincoln did not explore in 1838) they dispensed patronage and deployed favoritism. This was not the prettiest glue a society could use to hold itself together, and it frequently descended into corruption, but patronage and favoritism worked in their own oppressive way.

Democracies would need social glue as well, but the glue which the American founders hoped to apply was a virtue. If Americans could be persuaded to deny themselves, to place the public interest first, and to govern with a view to truth, even to their own personal harm, then the United States would prosper. Self-government in a nation could only flourish in an atmosphere of personal self-government, supported (as John Adams insisted in 1776) “by pure Religion, or Austere Morals. Public Virtue cannot exist in a Nation without private... Virtue.”

The problem with virtue, however, was that it demanded more of people than they might be willing to give. In the same year that Americans declared their independence, Adam Smith declared in The Wealth of Nations that “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker, that we expect our dinner but from their regard to their own interest. We address ourselves, not to their humanity but to their self-love, and never talk to them of our own necessities but of their advantages.” By 1787, there were a good many sadder but wiser Americans who agreed: the only way to make the American republic work was by appeals to self-interest. “Individuals of extended views and of national pride may bring the public proceedings to” the “standard” of virtue, complained James Madison, “but the example will never be followed by the multitude.” What was true in economies was true in politics: the real governor of human behavior was self-interest, not a virtue. “If men were angels, no government would be necessary,” Madison conceded. But they were not, and so “ambition must be made to counteract ambition.”

But if virtue was difficult for democracies to practice, was self-interest not toxic? And did that explain why democracies were so short-lived? Abraham Lincoln believed as profoundly in self-interest as Adam Smith. “We have been mistaken all our lives if we do not know” that “everybody you trade with makes something.” Lincoln “maintained that there was no conscious act of any man that was not moved by a motive, first, last, and always,” wrote William Henry Herndon of his old law partner. Even when Lincoln was arguing for the recruitment of black men as Union soldiers, he framed the argument in terms of self-interest rather than virtue. “Negroes, like other people, act upon motives,” Lincoln reasoned. “Why should they do anything for us if we will do nothing for them?”

But he did not believe that self-interest alone could sustain a democracy. Even Madison had constrained political self-interest by the Constitution’s separation of powers; Lincoln believed that there was a natural law in morals which restrained self-interest in democracy. In any question of policy, then, “let us be brought to believe it is morally right”; but, at the same time, he added, let us believe that it is “favorable to, or, at least, not against, our interest.” It was slavery, he believed, which insisted “that there is no right principle of action but self-interest.” Slavery was the instrument of men “bent only on temporary self-interest.” So, as much as Lincoln believed that self-interest was too instinctive a rule in human society to deny completely, he also believed that there was a circle to be drawn around certain tenets of natural law which neither self-interest nor majorities could invade.

Nothing showed this to better effect than the series of debates Lincoln held with Stephen A. Douglas during the campaign for the senior U.S. Senate seat from Illinois in 1858. For Douglas, democracy was really simple majoritarianism: whatever 51% of the people wanted for the nation ought to be the rule. What mattered most in Douglas’s mind was the process — whether the rules of counting the majority had been properly observed. Once that requirement was satisfied, Douglas cared not at all whether slavery was “voted up or voted down” in the territories. “Let the voice of the people rule.” This was an example of what Michael Sandel has called the “procedural republic,” which treats its citizens strictly as independent individuals who have rights. Since, in Douglas’s reasoning, slave-owning was a constitutionally guaranteed and morally neutral right, it was no business of anyone in the free states to interfere with the free exercise of that right.

Lincoln represented an entirely different perspective. Democracy was not about helping people exercise rights apart from doing what was right. Even if slavery was legal by certain state laws, it was nevertheless a clear violation of natural law. No majority, of 51% or any other percent, had the power to reverse natural law, and certainly not the natural laws Lincoln could find written in the Declaration of Independence about life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, or in physical nature and the instinctive resistance of the humblest creatures to oppression and exploitation by members of their own species. “The ant, who has toiled and dragged a crumb to his nest, will furiously defend the fruit of his labor, against whatever robber assails him,” Lincoln declared, which made the wrong of slavery “so plain, that the dumbest and stupid slave that ever toiled for a master, does constantly know that he is wronged.” In the face of Douglas’s belief that democracy existed only to provide a procedural framework for exercising rights, Lincoln insisted that democracy had a higher purpose, which was the realization of a morally right political order. For Douglas, democracy was an end in itself; for Lincoln, it was a means rather than an end, a means in the political life of realizing the natural ends for which men were made.

Natural law had been a source of restraint and appeal for centuries before Lincoln. The audiences to which he appealed in 1858 understood what he was talking about even if they balked at his application of it to slavery. In 1859, all of that fell to pieces. Charles Darwin’s Origin of Species, published in November of 1859, set out a vision of a world system from which all laws except that of self-interest were fully and finally banished. Lincoln died before the full effect of Darwin’s ideas could draw any form of a comment from him. But the democratic project that Lincoln felt was a full and satisfactory statement of the truth of human nature could, after Darwin, no longer justify itself in any terms other than the simple satisfaction of human demands — and in that case, monarchies, oligarchies, and dictatorships might serve those ends just as well as democracy.

World War One’s aftermath saw Europeans plunge into an orgy of constitution-making, seeking to replace the dynasties toppled by the war — the Habsburgs, Hohenzollerns, Romanovs, and sultans — with a world made safe for democracy — only to see those democracies, bereft of any moral law, crumble and collapse before more insidious but also more effective appeals to self-interest. And even when, in 1989, democracy achieved its most notable victory in the collapse of the Soviet Union and its empire, it still managed (as Paul Berman wrote in Terror and Liberalism) “in its pure version... to seem mediocre, corrupt, tired, and aimless, a middling compromise, pale and unappealing something to settle for, in a spirit of resignation.”

|

| Salmon P. Chase |

By contrast, Lincoln was not nearly so limp in his embrace of democracy. Self-interest has a role to play, but so does confidence in the moral right. And yet, even that confidence had to obey the iron rod of democracy’s operating rules. Right without law was little better than Douglas’s law-without-right, or even lawlessness itself, and he did not believe that democracy could survive without both determined advocacy of natural right and an equally determined acquiescence to the rule of law. When his earnest Treasury Secretary, Salmon Chase, urged him to step beyond the Emancipation Proclamation and unilaterally emancipate all slaves everywhere in the United States (rather than just the Confederacy), Lincoln replied with a sharp reminder that this unilateralism, even in the name of freedom, was exactly what put democracy in danger. “If I take the step,” Lincoln argued, “must I not do so, without the argument of military necessity, and so, without any argument, except the one that I think the measure politically expedient and morally right? Would I not thus give up all footing upon constitution or law? Would I not thus be in the boundless field of absolutism?”

The question before us is whether the confidence Lincoln reposed in democracy is still possible. In our universities, critical theory tells us that, just as all biological entities reduce to survival, all human relationships reduce to power, so that what calls itself democracy is really only a linguistic cloak for the same power employed by dictatorships; in our streets, what Lincoln would have at once recognized as his old nemesis, “that lawless and mobocratic spirit... spreading with rapid and fearful impetuosity, to the ultimate overthrow of every institution, or even moral principle,” insists that it, and not the laws, is the vehicle of justice; even in the halls of Congress, a sitting U.S. Senator announces that “democracy is unnatural,” that “we don’t run anything important in our lives by democratic vote other than our government,” so “it’s illogical to think it would be permanent. It will fall apart at some point, and maybe that isn’t now, but maybe it is.” These are words we have not heard since 1860, and they appall us with the thought that the ghosts of 1860 have reappeared on the stage of our public life to try us once again. Where, then, shall we find an antidote to this pessimism about the democratic future?

|

| Young Lincoln Giving a Public Speech. |

When he spoke to the Wisconsin State Agricultural Fair in 1859, Lincoln described “an Eastern monarch” who “once charged his wise men to invent him a sentence... which should be true... in all times and situations.” They came back with this formula:

And this, too, shall pass away. This was, Lincoln acknowledged, a useful saying, “consoling in the depths of affliction!” But he did not want it to be the epitaph of democracy. “Let us hope it is not quite true,” he continued. “Let us hope, rather, that by the best cultivation of the physical world, beneath and around us; and the intellectual and moral world within us, we shall secure an individual, social, and political prosperity and happiness, whose course shall be onward and upward, and which, while the earth endures, shall not pass away.” To which I, for one, can only say, let it be so.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Contributor, Allen Guelzo