Since the late 1800s, Chicago was known as the "candy capital of the world."

Chicago has many ties to the chocolate industry. Charles "Carl" Frederick Günther, known as "The Candy Man," opened his own candy factory and store at 125 South Clark Street in Chicago in 1868. He originated and introduced caramels, a staple product of most candy factories ever since.

The World's Columbian Exposition of 1893 featured a chocolate pavilion, a cocoa mill, a 38-ft. chocolate statue, and German chocolate-processing machines on display and available for sale. Milton Hershey purchased one of these chocolate-making machines and used it to make chocolate back in his home state of Pennsylvania. The first Hershey bar was produced in 1900. Hershey's Kisses were developed in 1907, and the Hershey Bar with almonds was introduced in 1908.

By the early 1900s, Chicago was home to over one thousand candy companies. The National Confectionery Association and The Manufacturing Confectioner magazine were founded in Chicago.

Emil J. Brach opened “Brach's Palace of Sweets” on North Avenue and Halsted Street in Chicago in 1904 and sold mainly chocolate bars and an almond nougat confection. After World War II, Brach's had more than 1,700 product lines.

|

| Brach’s Confections, "Brach's Palace of Sweets," Chicago. |

Johnson’s Candy Company developed Turtles candy in 1918 when a traveling salesman showed a piece of candy to one of the chocolate dippers because it looked like a turtle. In 1923, the candy maker’s stores dropped the "Johnson’s" name and was renamed DeMet’s, Inc., located at 177 North Franklin Street, Chicago. DeMet’s immediately trademarked the name "Turtles."

The first Fannie May candy shop was opened at 11 North LaSalle Street in 1920 by H. Teller Archibald, a prominent Chicago racehorse owner. The business was booming—by 1935, it had grown to 48 retail shops in Illinois and surrounding Midwest states. Key to the company’s success was its collection of decades-old candy recipes that, over the years, it refused to update or modernize. In 1946, Fannie May created “Pixies,” their most popular product. Since 2017 the company is currently owned by "Ferrero SpA" in Italy.

Ferrara Pan, a Chicago-based company’s claim to fame, was the introduction of Bit O’ Honey in 1924, a honey-flavored taffy product with bits of almond embedded throughout.

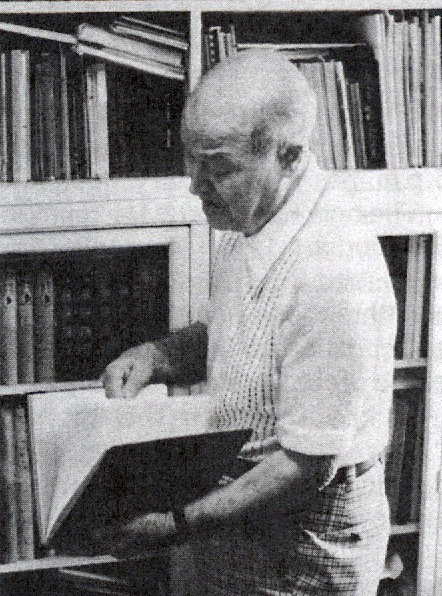

Aurora “Ora” Henrietta Hanson was born in 1876 in Michigan City, Indiana. When she achieved renown as a businesswoman, her origin story appeared in dozens of newspaper and magazine articles: her mother died when she was 3 years old, leaving her and her siblings with their sea captain father. Not allowed to have store-bought candy, young Ora learned to make confections for the family.

|

| Aurora “Ora” Henrietta (Hanson) Snyder. |

She married William Allen Snyder in 1894 and had one daughter, Edith. In 1909, William became ill, leaving Ora to consider how she might support the family should he not survive. She got to work making candy at home to sell at a local school, and her reputation grew enough to seek out other opportunities to sell her candy in Chicago. In 1910, she rented a nine-foot-wide store in the Hamilton Club Building.

From the start, Snyder’s business model came from her personal experience: people buy what they like. She focused less on her competitors and more on who her customers were and what they wanted. She gave out free samples to entice sales.

Another keen observation was that men bought more candy than women and preferred chewier and saltier varieties. She expanded her commercial ventures by opening new shops, not in shopping districts but in male-dominated business areas such as the Board of Trade Building.

Mrs. Snyder marketed her brand to emphasize that she was a real person who cared about quality and her customers. Framed photographs of her hung in each shop with the message “Mrs. Snyder thanks you.” Early on, she recognized the benefits of pre-packaged candies and intentionally developed no-frills packaging.

|

| Mrs. Snyder’s candy boxes bear her seal of approval and the words, “I can’t make all the candy in the world, so I just make the best of it!” |

By the early 1920s, Mrs. Snyder’s had expanded to five locations, including a seven-story building at 119-21 North Wabash Avenue.

| |

| Vintage candy tin from Mrs. Snyder's Candy Shops. The tin features a Noblewoman being serenaded by the court musician. |

In addition to her business, Snyder helped found the Associated Retail Confectioners of the United States, serving as their President between 1930 and 1932. She was also a Chicago Business and Professional Woman’s Club member and regularly gave speeches to similar groups.

By 1932, Mrs. Snyder's Candies had eleven downtown stores:

- 2030 East 71st Street, Chicago.

- 20 South Dearborn Street, Chicago.

- 61 West Jackson Boulevard, Chicago.

- 8 South LaSalle Street, Chicago.

- 331 South LaSalle Street, Chicago.

- 222 West Merchandise Mart Plaza, Chicago.

- 406 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago.

- 218 South Michigan Avenue, Chicago.

- 1813 West Montrose Avenue, Chicago, IL. (H.Q. & Kitchens)

- 65 West Randolph Street, Chicago.

- 119-21 North Wabash Avenue, Chicago.

- 130 South Wabash Avenue, Chicago.

- 79 West Washington Street, Chicago.

- 104 North Oak Park Avenue, Oak Park, IL.

- 716 Church Street, Evanston, IL.

- 1739 West Howard Street, Evanston, IL.

Ora Snyder's business instincts kicked in when she set up five shops at the Century of Progress International Exposition for the fair's second year in 1934. One was on the western approach to the 23rd Street bridge, and the four other shops were on the south of the wide promenade connecting the mainland with Northerly Island, just east of the Streets of Paris.

Each store featured a candy kitchen in full operation, separated by large plate glass windows for visitor viewing. The favorite feature of the stores was the cutting-edge air conditioning and an ice cream machine. Air conditioning was still a novel feature in 1934, and it drew large crowds seeking relief from the summer heat, but it also kept the candy from melting and the workers from heatstroke.

Soon after, newspaper headlines announced, “Mrs. Snyder Decides to Air Condition all of her Stores” after her success at the World's Fair.

Ora Snyder continued to be active in the business until 1947, when she stepped down as head of her company due to illness. She died in Chicago in 1948 at 72, leaving behind sixteen shops in the Chicagoland area and hundreds of employees.

William Snyder served as Chairman of the Board for Mrs. Snyder’s until he died in 1955. The business remained in the family with son-in-law Seymour W. Neill and grandson William J. Neill until it became part of Fannie May in 1967.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

.jpg)

.png)

.png)