William Frederick Cody was born on February 26, 1846. As a young man, Cody won renown and an indelible nickname for his authentic, embellished, and imagined exploits on the Great Plains.

Buffalo Bill Cody claimed to have killed 4,280 bison in approximately 18 months (548 days) while supplying meat for Kansas Pacific Railroad workers. 4,280 bison / 548 days = 7.8 bison single-handedly killed per day.

But it was in Chicago that Buffalo Bill embarked on his celebrated career as a showman extraordinaire. Cody was among a handful of civilian scouts awarded the Medal of Honor for courage in battle.

The Famous Buffalo Bill Cody vs. William "Bill" Comstock Shooting Competition likely happened sometime in the late spring or early summer of 1868, near Sheridan, Kansas, along the Kansas Pacific Railway. The contest was an eight-hour competition to see who kills the most buffalo. The prize was $500 ($10,800 today, 2024) and the official title of "Buffalo Bill." William "Buffalo Bill" Cody and William "Buffalo Bill" Comstock were both expert scouts, buffalo hunters, and trackers.

It was recorded that Buffalo Bill Cody killed 68 buffalo to William Comstock's 48.

|

| William F. Cody's Medal of Honor, April 26, 1872 |

Chicago knew the intrepid frontiersman early on. The first installment of "Buffalo Bill: The King of Border Men" — the sensational tale by dime-novel fabulist Ned Buntline that brought 23-year-old Cody national fame — appeared on the front page of the Chicago Tribune on December 15, 1869.

Cody first visited the city in February 1872, exchanging his fringed buckskin for a store-bought 'monkey suit' before attending an elegant ball. "Here, I met a bevy of the most beautiful women I had ever seen," he remembered. "Fearing every minute I would burst my new and tight evening clothes, I bowed to them all around — but very stiffly."

|

| Buffalo Bill Cody |

Before year's end, Cody returned to the city, summoned by Buntline to star in his new play. "Scouts of the Prairie" opened on December 16, 1872, at

Nixon's Amphitheatre, a foul-smelling, canvas-topped venue on Clinton Street (not far from today's Ogilvie Transportation Center). Without exception, the city's newspapers panned the lively but ludicrous melodrama.

Theatergoers didn't care. Despite his limited acting skills — the Tribune critic claimed Cody delivered his lines "after the manner of a different school-boy in his maiden effort" — Chicagoans loved Buffalo Bill. Full of sound and fury, the play, with its tall, ridiculously handsome leading man, "attracts more people than the house can hold," noted the Tribune. "Crowds are turned away nightly."

For the next few years, Cody divided his time between the Plains, where he served as an Army scout, and the theatrical circuit, where he led his acting troupe, Buffalo Bill Combination. From 1874 to 1886, "Bison William" (as one Tribune wit dubbed him) performed dozens of times at the Olympic, Criterion, Adelphi, and other long-vanished Chicago theatres. He headlined in such fare as "Knight of the Plains," "The Prairie Waif," "Buffalo Bill's Pledge," and "May Cody," a contrived Western romance involving Cody's sister.

|

| Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show, 1883 |

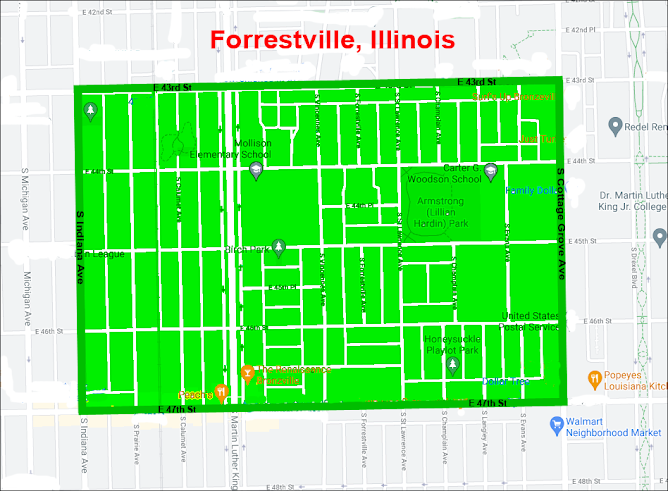

Cody assumed his most famous role in October 1883 when he brought "Buffalo Bill's Wild West" to the Chicago Driving Park, a horse track on the city's West Side (immediately west of today's Garfield Park; see map below). The "Wild West" featured scores of cowboys, scouts, buffalo hunters, and Cheyenne, Pawnee, and Lakota men and women in an outdoor extravaganza. Open to the public, the Native American encampments attracted throngs of curious onlookers throughout the decades-long run of Cody's traveling show.

|

| Buffalo Bill Cody, with three Indians from his Wild West Show. Date unknown. |

Confident they were seeing, as advertisements promised, "genuine illustrations of life on the plains," Chicagoans were thrilled to spine-tingling reenactments of buffalo hunts, Pony Express riders, stagecoach attacks, and, in later years, Custer's Last Stand. Staples of the show were rodeo acts and "marvelous shooting" exhibitions, at which Cody excelled.

In the May 1885 Chicago appearance of the "Wild West," a diminutive young woman named Annie Oakley outshone even Cody with her marksmanship. She'd remain a star attraction of the show for 17 seasons. A mob of newspaper reporters greeted America's darling sharpshooter, Annie Oakley.

|

| Annie Oakley was born Phoebe Ann Moses on August 13, 1860, in Darke County, Ohio. Her family called her Annie. Oakley joined Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show in 1885 with her name on advertising posters as "Champion Markswoman." |

Thanks to the work of his manager, Nate Salisbury, Buffalo Bill was invited to perform at London's American Exhibition in 1887. His voyage across the Atlantic included "83 saloon passengers, 38 steerage passengers, 97 Indians, 180 horses, 18 buffalo, 10 elk, 5 Texan steers, 4 donkeys, and 2 deer." Before the show opened, the camp was visited by former prime minister William Gladstone, the Prince of Wales (future King Edward VII), and his family. Annie Oakley even shook hands with the Prince, and he was so charmed—despite the breach in etiquette—that he encouraged his mother, Queen Victoria, to see it.

|

| Buffalo Bill in London, 1887 |

A performance was arranged for May 11, 1887. Queen Victoria appeared in person at a public performance for the first time since her husband's death two decades earlier. She liked it so much that she asked for another performance on the eve of her Jubilee Day festivities, with the kings of Belgium, Greece, and Denmark and the future German Kaiser William II in attendance. The twice-a-day performances at the American Exhibition averaged crowds of 30,000 at 50¢ admission ($15 today).

Yet his mettle would be tested many years later by a man who drafted blueprints and knew nothing of warfare on the Western plains. Cody often thought it was the most satisfying performance of his life.

|

| Buffalo Bill Cody |

Daniel Hudson Burnham, the foremost architect in Chicago, Illinois, was appointed the director of works for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. The official name of the Fair, the World's Columbian Exposition, commemorated the 400th anniversary of Columbus's discovery of America. Upon his selection, Burnham wrote a prophetic entry in his daily journal: "Make no little plans; they have no magic to stir men's blood . . ."  |

| Daniel Hudson Burnham |

Cody immediately grasped an opportunity from his ranch in Nebraska in the Columbian Exposition. His "Buffalo Bill's Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World" show had recently returned from a hugely successful tour of Europe. Ever alert to profitable ventures, he foresaw fortune awaiting at the World's Fair. He promptly dispatched his partner and business manager, Nate Salsbury, to Chicago.

The exposition's Committee of Ways and Means was the governing body for all concessions at the Fair. Salsbury made an enthusiastic pitch, extolling the wonders of Buffalo Bill's Wild West extravaganza. After due consideration, the committee informed Salsbury that the tariff for a concession was 50% of gross proceeds—not [net] profits, but 50¢ of every dollar collected for admission.

When Salsbury returned to Nebraska, we can only imagine Cody's reaction. He probably shouted something on the order of: "Fifty percent! Who do those SOBs think they are?"

Within a short time, he would learn who they were and, more importantly, the grandeur of their plans. The Columbian Exposition was envisioned as the most spectacular attraction in the world.

Cody was not one to be denied. The exposition was scheduled to run six months, May 1 to October 30, and he meant to be there—without handing over 50% of his gate receipts. He dispatched Salsbury again to Chicago, where the manager leased about 14 acres of undeveloped land at Stony Island Avenue and 63rd Street, opposite Jackson Park, for the encampment.  |

| Just west of the World's Fair. See the Map Below. |

|

| The entrance to Buffalo Bill's 1893 Wild West show and encampment was on 62nd Street, just west of the Fair's 62nd Street entrance. |

On March 20, a long train carrying the Wild West show arrived at the rail yards. Unloaded from the cars were 100 former cavalry troopers, 46 cowboys, 97 Cheyenne and Sioux Indians, 53 Cossacks and Hussars, and several herds of animals, including horses, buffalo, and elk. In a game of one-upmanship, Buffalo Bill's Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World opened on April 3, four weeks before the exposition.

The 50¢ admission to the show was more affordable than the World's Fair, which also charged 50¢ admission but had separate admission costs for most exhibits on the Midway Plaisance.

|

| Buffalo Bill Day was the show's last day. It closed on purpose one day after the World's Columbian Exposition! |

The show presented bronco busters and wild animals, a cowboy band tooting popular tunes, a choreographed Indian attack on the Deadwood stagecoach (vanquished by mounted troopers), and a realistic staging of "Custer's Last Stand." In daring feats of marksmanship, Oakley blasted an impossible array of targets, and Cody, on horseback, shattered glass balls thrown into the air. On some days, every seat in the 18,000-seat arena was sold out.

|

| Buffalo Bill at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. The Fair authorities allowed the Wild West show to parade through the Exposition grounds weekly. |

Cody often upstaged the exposition. On one occasion, World Fair officials flatly refused a request by Mayor Carter Harrison that poor children of Chicago be admitted for one day at no charge. Ever the consummate showman, Cody immediately announced a "Waifs Day" (Old French term; "stray beast," designates a homeless, forsaken, or orphaned child) at the Wild West show.

Cody offered every child from Chicago free train tickets, free admission to his performance, and free access to roam the Wild West encampment. To top it off, he also gave them all the candy and ice cream they could eat. Fifteen thousand children of all races swarmed the Wild West show, and Cody was hailed as a "champion of the poor."

Waifs Take A Bath

Chicago Tribune, July 26, 1893

HOMELESS BOYS AND GIRLS GET THEIR ANNUAL SCRUBBING

Some hundreds of children to whom the word "home" conveys no meaning, many of whom have no recollections of their parents, and still others to whom the mention of father or mother only conjures up feelings of lothing and fear, enjoy the rare luxury of being clean and decently clothed yesterday, Tuesday, July 25, 1893. Though the exertions of Superintendent Daniels and his fellow-workers of the Chicago Waifs Mission & Training School little wanderers of the street of both sexes and all colors enjoyed their annual bath.

There may be some to whom the idea of an annual bath is highly amusing. There was nothing amusing in the scene on the lakefront yesterday. Hundreds of boys, some of them with crutches, stood patiently in line for hours before a small tent east of Michigan Avenue, between Randolph and washinton streets. The high wind caught up loose dirt and whirled it about through the crowd in dense clouds, filling eyes, ears, and noses until the grimy urchins almost lost their identity. Dirty clothes were made still dirtier and the discomfort of standing for hours in a broiling sun was greatly intensified. Those who passed through the tent and came out clean did not remain so until they got fifty feet away. That cloud of dirt and street sweepings immediately covered their moist skins until they were as black as before. If someone had sent a street sprinkler down there all this discomfort for the children and their grown up friends who were working so hard for them could have been done away with. But no one sent the sprinkler.

Inside the tent three barbers armed with clippers worked as they never worked before removing unkempt locks. As fast as their hair was cut the boys were passed along the line to half a dozen muscular men. Dirty and sometimes filthy rags were quickly striped off, the boys were plunged into tubs, and the attendants begam with stiff brushes and plenty of soap upon the dirt accumulations of months. Superintendent Daniels was there himself with a scrubbing brush until he was tired out. Then he went outside to issue checks to the washed throng for clothes. ATTENDANTS SCRUB WITH VIGOR

The attendants were none too gentle in the way they handled those still brushes, but not once was a wimper of complaint heard. The boys were only too glad to be clean once in twelve months. They would be clean all the time if they could.

But if they love cleanliness why are the newsies selling papers and bootblacks shining shoes for pennies enough to keep soul and body together always so dirty? Where are they to go for a bath, even once a week? They cannot spare the price of even one bath from their scanty earnings, and even if they could there isn't a public bathhouse in the city those unkempt younsters would be allowed to enter. They cannot wash at home, for they have no home. If they attempted to bathe in the lake they are promptly arrested by policeman. There are no free public bathhouses in this city of nearly two million people. The only thing these boys can do is to wait, and push, and struggle, endure great physical discomfort, and miss the sale of their papers for a part of the day, which means that they shall also miss what passes with them for dinner, for the privilege of being clean once in a year.

After the bath came the distribution of clothing. Two hundred boys stood in line patiently waiting their turn while another hundred who did not know Superintendent Daniels so well swarmed around him, not rough and noisy but only afraid, so very much afraid, that the badly needed clothing would all be gone before their turn came and that for months longer they would have to wear the rags that hardly covered thei nakedness. Never once did a harsh word escape Superintendent Daniels, though he was so closely beset that for hald an hour he could do nothing but expostulate. Finally he was forced to take a piece of board and push back broad sides of the boys until he had dressed the the line into order.

Some of the women teachers were on the ground at times. These, like Superintendent Daniels, were treated with the utmost respect by the children. Some of the smaller boys were met by these teachers going sorrowfully away without the coveted bath. They were worn out with waiting in the hot sun and the dust. The only comfort these teachers could offer the disappointed little ones was the assurance that next year they should have a nice wash and some clean clothes. Wait a year for a bath!

Possibly the city might have lent a hose to be connected with the nearest hydrant, thus affording a plentiful supply of water at least, but the city did not do this, so the water was hauled in barrels.

GIRLS GET A CLEANSING, TOO

Up at the Chicago Waifs Mission & Training School, homeless, fatherless, motherless girls were also going through the cleansing process and were afterward given new dresses, new shoes, and new hats. A few mothers were there with babies that needed washing and clean clothes. The girls were taken upstairs, where half a dozen women presided at the tubs. The manes of every one of these women are familiar to the readers of society news. they came early in the morning, put on old wrappers, rolled up their sleeves, and went to work, hard, earnest work, until they were exhausted. Other women watched over the distribution of clothes. More than 300 girls were made clean and provided with new clothes. Here are the firms that helped to give these boys and girls a bath and to clothe them afterward: Edson Keith & Co., Keith Bros., Gage Bros., Sweet, Dempster & Co., Phelps Dodge & Palmer, Sampson, Lowe & Co., Gus the Square hatter, C.M. Barnes, King & Bro., Putnam, Felix & Marston, and Mann Bros.

Six hundred boys and three hundred girls were cared for by the Chicago Waifs Mission & Training School workers yesterday. In the afternoon those who had been fortunate enough to get their baths and their clothes in the morning went to the Auditorium, where a benefit was given for them by the theatrical profession. All afternoon up to the close of the preformance squads of breathless boys and girls, their faces shining with expectancy and soap, would come rushing up the stairs, cast one awe-struck, admiring glance around at the beauties of the parquet and the handsomely dressed women and children in it, then go tearing up the steps, up, up, to the topmost galleries, where for once thay might sit in comfortable chairs, watch the wonders of the stage, and, watching, forget their wretchedness.

The house was well filled. There were sixteen box parties. The theatrical profession was generous in volunteering their services, and the program was a long one. Lillian Russell, Sol Smith Russell, Eissing-Scott, Henry Norman, Herman Bellstedt Jr., Col Thomas H.Monstery, Genevra Gibsom, Denman Thompson's double quartet, Annabelle, Richard Pitrot, Tilly Morrissey, the three Marvelles, and Iwanoff's Imperial Russian troupe took part.

TO SEE THE WILD WEST SHOW

Tomorrow, Thursday, July 27, 1893, children will attend Buffalo Bill's Wild West Show. They will be in condition to enjoy it in truth, for each youngster will be given all thay can eat before entering the show. The Illinois Centralwill transport the waifs to Sixty-third street and Stony Island Avenue. Across the World's Fair grounds was a piece of vacant property owned by J.Irving Pearce, which has been placed at the disposal of the children. Here a booth has been put up, where lemonade was made and lunches distributed. Each and every boy and girl will get a glass of lemonade served in the biggest glasses it is possible to find anywhere and an extra large lunch, larger than the hungrist boy could possibly eat at one time, neatly put in a paper box. Then for the show.

Buffalo Bill will give a special performance for the waifs earlier than usual so the boys can get back to their special trains in time to sell their papers at 4 o'clock. "Buffalo Bill's heart is bigger than his hat," said one of the woman teachers at the Chicago Waifs Mission & Training School, "and any one who has seen the latter knows that is saying a gread deal. When we asked him if we might bring the children down to see the show he replied, 'Why, of course; bring as many as you like.' "Can we bring 10,000?" I asked. 'Bring 20,000 if you like,' was his answer."

World's Fair President, Harlow Niles Higinbotham, was asked to let the children march through the grounds from one end to the other with the teachers accompanying to explain what the various buildings were and to keep them in order. They were not to enter any of the buildings. The teachers pledged themselves that the children should not break ranks, step on the grass, or do anything at all out of the way. It was to be simply a march through the grounds.

But Higinbotham said peremptorily (subject to no further debate or dispute), "NO!"

Buffalo Bill's Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World closed on October 31, 1893, a day after the World's Fair. During its engagement, an average of 16,000 spectators attended each of the 318 performances, for an overall attendance exceeding five million. In the end, Cody departed Chicago with $1 million in cash ($30 million today) and the irony of the last laugh. He never paid Burnham or the World's Columbian Exposition one red cent. He used part of the proceeds to found his namesake town, Cody, Wyoming; build an extensive fairground for North Platte, Nebraska; and retire the debts of five Nebraska churches. The balance went toward expanding the panorama of his Wild West extravaganza.

Buffalo Bill left town a hero, so he remained on each subsequent visit to Chicago: more than 100 performance dates over the next 23 years. Touring the world, the hard-drinking Cody continued to make lots of money, which he steadily lost to bad investments and extravagant living. In July 1913, two weeks after an 11-day engagement in Chicago, creditors foreclosed on his show.

The man who once bedazzled European royalty toured with a second-rate circus. His last appearance here came over nine days in August 1916 when he served as little more than a mounted prop at the Chicago Shan-Kive and Round-Up ("shan-kive" was a Ute word meaning "celebration"). The venue for this farewell? The old

West Side Park #2 (at Polk Street and Wolcott Avenue) is where the Cubs won the World Series in 1907 and 1908.

Cody died at the Denver home of his sister May on January 10, 1917. He is buried at the Buffalo Bill Memorial Museum, City of Golden, Jefferson County, Colorado. Louisa Maud Frederici Cody (1843-1921) married William Frederick Cody on March 6, 1866. The Colonel made arrangements if he was to die first. Col. Cody was interned in a vault blasted eighteen feet deep from solid rock. His casket rests upon concrete pedestals, and over it is covered a substantial arch. The grave is to be opened, and the coffin of Mrs. Cody is to be placed above that of her husband; thus, the two will be sleeping in one grave.

In an editorial the next day, the Chicago Tribune celebrated the "illusion" created by Buffalo Bill. "A fact, after all, is not all true," the Tribune contended. "Truth is fact — perfected by our dreams and emotional reactions. This will live with us while mere facts sink into the shadows of the forgotten past. They are dead, and the credence we give facts makes them immortal."

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

WILLIAM "BUFFALO BILL" FREDERICK CODY

BUFFALO BILL'S HISTORY WAS MOSTLY FABRICATED.

The Pony Express began in the spring of 1860 and lasted 19 months. Its purpose was to get the U.S. Mail across the country as fast as possible. California, a state since 1850, was filling up with white people. The forces that soon would lead to civil war were pulling the nation apart. If the United States was going to hold together, there had to be fast, reliable communication between the West Coast and the centers of power in the East.

Bill Cody was 14 years old, so the story goes when he made his world-famous ride for the Pony Express. Leaving Red Buttes on the North Platte River near present-day Casper, Wyoming, he galloped 76 miles west to Three Crossings on the Sweetwater River. His route took him along what we now call the Oregon/California/Mormon Trail. A station—at least a rough cabin and a horse corral—was along the road every 12 miles. Bill would have jumped off his sweaty horse at each station and onto a fresh one.

As he dismounted, he drew the mochila—the leather saddle cover with special pockets for the mail—from the saddle and threw it over the saddle of the horse the wrangler brought up. This happened in seconds, and there was no time to lose.

When he arrives at Three Crossings, the story goes on. Bill found that Miller, the rider who was to take over for him, had been killed the night before in a drunken brawl.

"I did not hesitate for a moment to undertake an extra ride of 85 miles to Rocky Ridge, and I arrived at the latter place on time," Buffalo Bill remembered many years later. Rocky Ridge was near South Pass. Another rider would have picked up the westbound mail young Bill delivered there. But the eastbound mail needed a carrier, too, to take it back the way he had just come. Bill volunteered again. When he got back to Three Crossings, the same man was, of course, still dead, and so Bill again transferred the mochila and galloped back to Red Buttes. The entire distance was 322 miles.

It was a thrilling ride made by a valiant boy who had been a great horseman all his life. By the time he was 50, Buffalo Bill was the most famous man in America, and his Pony Express ride was one of the reasons for his stardom.

But Bill had things mixed up. For one thing, Three Crossings and Rocky Ridge are only 25 miles apart, not 85. For a second thing, much more important, he never did make the famous ride. In fact, William Frederick Cody never rode for the Pony Express at all.

WILLIAM F. CODY'S BACKGROUND

Young Will Cody was born in 1846 into a middle-class family on the Iowa frontier. After moving to Kansas in the 1850s, the family was thrust into poverty by the violence leading up to the Civil War. Will Cody's father, Isaac, was a surveyor, a founder of towns, a real estate investor, and a locator of land claims. On September 18, 1854, during a dispute at a political meeting at Rively's trading post, a pro-slavery sympathizer stabbed him twice in the chest with a Bowie knife. Complications from the injury ultimately led to his death in 1857. Meanwhile, Will had to find work to help support his mother and sisters.

When he was just 11 years old, he took a job carrying messages on horseback for the freighting firm of Majors and Russell. He rode from the company's offices in Leavenworth to the telegraph office at Fort Leavenworth, three miles away.

Majors and Russell soon became Russell, Majors, and Waddell, the largest transportation company in the West, which owned stagecoaches, thousands of freight wagons, and tens of thousands of horses, oxen, and mules to pull them, as well as a network of stations, corrals, and employees across the West. This was the company that started the Pony Express system in 1860. Because young Will had worked for them briefly when he was 11, it may not have seemed to him such a stretch later to claim he had, in fact, ridden for the Pony Express when he was 14 years old.

Will Cody's actual teenage years were troubling, not thrilling. When Congress made Kansas a territory in 1854, lawmakers left it up to local people to decide whether to allow slavery. Armed men poured in; some supported slavery, and some opposed it. Elections were often violent. For a time, "bleeding Kansas," as it was called, had two territorial legislatures. One supported slavery, one opposed it, and each claimed to be the territory's legal, rightful lawmaking body.

During the late 1850s, Will Cody took jobs driving horses and wagons to places as far away as Fort Laramie, Wyoming, and Denver, Colorado. During the 19 months of 1860 and 1861, when the Pony Express was an ongoing concern, he was in school in Leavenworth. He could not have been riding back and forth across what's now central Wyoming at the same time on the Sweetwater Division of the Pony Express.

The Civil War broke out nationwide in April 1861. Sometime in 1862, young Will, consumed by a desire to avenge his father's death, joined the Kansas Redlegs, an anti-slavery militia. These men and boys were not regular soldiers; they were unpaid and lived only on what they could steal, according to Louis Warren's 2005 book, "Buffalo Bill's America." Mostly, the Redlegs stole horses and burned farms. More so, even than other militias in Kansas and Missouri, they were criminals. They paid little attention to whether the families whose farms they burned were pro- or anti-slavery, or pro-anti-union. Young Will Cody rode with them for about a year and a half.

Later in the war, he joined a regular Kansas regiment of the Union Army, and his soldiering became more respectable. After the war, he worked in western Kansas for a meat contractor that provided food for crews building the Kansas Pacific Railroad of the Union Pacific Railroad. His job was to kill buffalo, and Cody delivered 12 bison daily to the hungry workers for a year and a half. It's estimated he killed more than 4,000 in one eight-month period, and he once killed 48 buffalo in 30 minutes, despite Cody supporting conservation measures like implementing a hunting season.

He became known as Buffalo Bill, one of several hunters on the plains with that nickname. He also became friends with a man who held various police jobs in the towns of western Kansas—James Butler Hickok, better known as Wild Bill Hickok. Hickok suddenly became famous in 1867 when a reporter for Harper's Weekly, a national magazine, wrote an article about him.

Soon, both Bills were the heroes of so-called 'dime novels.' Authors of these cheaply made, pulp-paper books used Hickok's and Cody's real names but made up their thrilling adventures. Part of the fun for the readers was separating fact from fiction—guessing what was confirmed in the stories and what wasn't.

Cody understood this. By the early 1870s, Hickok, Cody, a friend named Texas Jack Omohundro, and Jack's Italian-born wife, Giuseppina Morlacchi, appeared together during the winters in stage plays around the West. Many of these they wrote themselves. The plays were full of scrapes, escapes, daring rides, fights, rescues, noble heroes, and evil villains—the same stuff that thrilled the dime-novel readers.

At the same time, the Indian wars on the plains were escalating. The U.S. Army always needed expert help to find its Indian enemies. Most of this work was done by other Indians and by mixed-race men. They were generally fluent in English and their mothers' Indian languages, making them valuable interpreters. But because of their race, the white officers were never entirely comfortable around them.

Cody was brilliant and friendly. The officers liked him because he liked to drink whiskey and tell stories and because he was white. But Cody also was comfortable around Indians in a way that most white officers were not. When it came time to chase Indian enemies, Cody stuck close to the Indian scouts and stayed ahead of the troops. When the enemy was found, Cody could take the credit for the discovery.

Soon, the officers praised him in their official reports and conversations with newspaper reporters. And they passed his name along to rich men looking for a guide for hunting trips. When Gen. Philip Sheridan arranged for Grand Duke Alexis, son of the Czar of Russia, to hunt buffalo in 1872, he made sure his favorite officer, George A. Custer, was along on the trip, and Cody was the guide. At Sheridan's suggestion, Cody persuaded Spotted Tail, chief of the Brule Lakotas, to visit the hunting camp in western Nebraska with many warriors and their families. The Indians staged large dances and killed buffalo with bows and arrows from horseback to entertain the bigwigs. Custer and the duke were the stars of the event, but the newspapers noticed Cody, too: "He was seated on a spanking charger," one columnist wrote, "and with his long hair and spangled buckskin suit, he appeared in his true character of one feared and beloved by all for miles around."

FAME

Cody was learning a lot about fame. He continued his double life, appearing in plays in the winter and scouting for the Army in the summers. Cody took part in a few skirmishes in the Indian wars, becoming part of his plays. Eventually, he wore his stage costumes when he went out on a campaign. A few weeks after Custer's defeat and death on the Little Bighorn in 1876, Cody scouted with the 5th Cavalry in western Nebraska.

When he encountered a Cheyenne warrior named Yellow Hair, he wore a red shirt with billowing sleeves and silver-trimmed, black velvet trousers. In the skirmish, Cody killed him and scalped him on the spot. He sent Yellow Hair's scalp, warbonnet, shield, and weapons home to his wife, Louisa, living in Rochester, N.Y., where it was displayed in a store window. Newspapers covered the story. The following winter, he toured with a new play, "The Red Right Hand, or Buffalo Bill's First Scalp for Custer," implying that Cody's was the first act of real revenge after the Custer fight.

When Cody was 33 years old in 1879, he published his autobiography. The book smoothed the stories of his early life and expanded his stock-driving jobs, supposed Pony Express service, and Indian skirmishes into dramas of frontier nerve, pluck, and progress. With the Indian wars on the plains all but over, with the buffalo nearly gone and the plains filling up with cattle, Cody must have realized that the demand for his scouting skills would only continue to shrink. But still, America was hungry for the other half of Cody's skills—his skills in show business.

BUFFALO BILL'S WILD WEST

In 1883, Cody and a partner named William "Doc" Carver put together a traveling show: part pageant, part circus, part rodeo, part parade, and part huge, open-air drama. It was built out of the same thrilling dime-novel and stage-play episodes Cody now knew and the episodes of his own life.

Versions of this show, known as Buffalo Bill's Wild West, ran for more than 30 years, from 1883 to 1916. Audiences loved it all over North America and Europe. In the earlier years, Cody found the most efficient way to make money was to park the show in a single spot near a large city—on Staten Island across the harbor from New York, for example, or in a 30-acre field outside Paris—and let the crowds come to him. After the show became well known in later years, the production had to travel constantly to find audiences still new enough to want to pay to attend.

The show featured mounted Indians attacking a stagecoach or wagon train and Indians attacking and burning a settler's cabin. The settlers were rescued at the last minute by a band of mounted men led by Buffalo Bill. The company included as many as 650 people in the most prominent years—cowboys, Indians, buffalo soldiers, sharpshooters, trick riders, trick ropers, cooks, wranglers, animal trainers, and all the laborers needed to set up, take down and move the show.

Indians played themselves. In 1885, they included Sitting Bull, victor of the Little Bighorn. Other well-known Chiefs and warriors took part over the years, including Spotted Tail, Red Shirt, and Standing Bear. The show even featured a pretend buffalo hunt.

Thanks to Buffalo Bill, all these events became central to America's ideas—and the world's ideas—about how the West was settled. For decades after Cody died in 1917, they appeared and reappeared in Western novels, especially Western movies. Year after year and decade after decade, the show seemed thrillingly real to its audiences. "Down to its smallest details, the show is genuine," Mark Twain, no stranger to the West, wrote Cody in an unsolicited fan letter in 1884. The word "show" was never in the show's actual title, and it was called "Buffalo Bill's Wild West," as though people could depend on it as a genuine article.

And year after year, decade after decade, the opening act was the one many found most thrilling: the Pony Express. A rider galloped at full speed to the grandstand and reined his pony back onto its haunches, front feet pawing the air. The rider leaped to the ground, lifted the mochila onto the next horse, and was off again at full gallop. The crowd was left breathless. Then, people burst into cheers and applause.

In their luxurious, 10-in by 7-inch printed programs, audience members could read about Buffalo Bill's adventures. What did it matter if they were true or not? They seemed true. Cody's genius lay in offering his audience what it needed to hear.

"Somehow," writes Texas novelist Larry McMurtry, "Cody succeeded in taking a few elements of western life—Indians, buffalo, stagecoaches, and Cody on his horse—created an illusion that successfully stood for a reality that had been almost wholly different."

His legacy, however, is very much alive. Promoters in Wyoming and the West have, since the turn of the 19th century, used techniques that Cody taught the world. Cheyenne's annual Frontier Days rodeo, still continuing today, was founded in 1897, partly with Cody's Wild West in mind. "Let's get up an old times day of some sort; we will call it 'Frontier Day,' Cheyenne Leader Editor E.A. Slack wrote that year. "We will get all the old-timers together, have the remnant of the cowpunchers come in with a bunch of wild horses, get out the old stagecoaches, and some Indians, etc., and we will have a lively time of it!"

By the 1920s and 1930s, dime novels had given way to western movies. Tourists were regularly driving to Wyoming to see Yellowstone Park—and cowboys. Articles in the Cody Enterprise urged locals to dress western to supply the visitors with what they'd come to see, especially during the week of the Cody Stampede: "Get on the red shirt and top boots and help put 'er on Wild. On June 1, the localities will be urged to don their eight-gallon hats and buckskin vests and 'go western' for the summer."

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.