Cloverdale, Illinois, was a small unincorporated DuPage county farm community located 25 miles west of Chicago at Army Trail Road and Gary Avenue in Bloomingdale township. Founded in 1888, the community became part of the Village of Carol Stream in 1959.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the area surrounding Cloverdale had been populated by German dairy farmers, and they founded a cooperative creamery to process their products. In business, at least as late as 1915, the creamery was not large enough to absorb the local milk production. Local farmers were looking for access to the Chicago market, hauling milk daily to a rail connection near Bloomingdale, Illinois.

In 1888 the Illinois Central railroad (IC) expanded routes in northern Iowa, connecting them to the IC's original Freeport to Dubuque trackage. But the IC lacked a direct eastbound connection to Chicago, routing through traffic east of Freeport over the Chicago Northwestern. The IC built its own connecting line from Chicago to Freeport to solve this problem, completing it in 1888.

|

| The Cloverdale Creamery was in the southwestern part of Bloomingdale Township in Cloverdale, Illinois. c.1910 |

The route was close to the Cloverdale Creamery, and a stop was established to service it. Much closer than Bloomingdale for the local farmers, Cloverdale became a central milk shipping point, giving them direct access to the Chicago market. The milk traffic was large enough for the IC to warrant constructing a large depot—home to a station master and his family—and a milk loading facility.

|

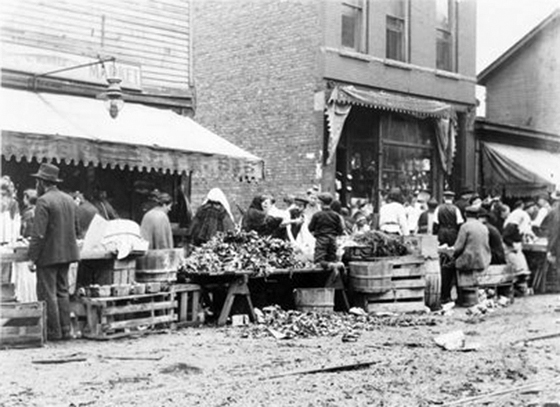

| Farmers lined up with milk cans on their wagons, waiting for the 10 A.M. eastbound Illinois Central train in front of Tedrahn's General Store. Tedrahn's was located next to the railroad. c.1905 |

Shortly after the line opened, a Chicago hotelkeeper, Charles Tedrahn, and his wife purchased land. They opened a general store on property north of the IC tracks, adjacent to the depot, and on the southwest corner of Cloverdale Road (later Gary Avenue) and Army Trail Road.

In 1888 Charles Tedrahn bought a one-acre site in Cloverdale, Illinois. He built Tedrahn's General Store, a two-story building elevated to a height that allowed easy loading from the storefront directly to the bed of horse-drawn wagons. There was a small picnic grove to accommodate the local farmers as they waited for the arrival of the milk train. The store stayed in the family till 1984.

In addition to food and hardware supplies, Tedrahn General Store became a US Post Office, sold Chicago newspapers dropped by the 7 IC trains serving Cloverdale daily, and provided notary services for the local farmers. Although never incorporated, various other civic functions for the community were housed at Tedrahn's. The basement was the local polling place, and dispatch for the local volunteer fire department was coordinated by the Tedrahn family. The steep front stoop was modified to accommodate two Standard Oil gas pumps.

In 1934 when the original store burned down, Tedrahn constructed a nearly identical single-story building on the old foundation and built living accommodations for his family behind the store. In 1946, during a wave of postal consolidation, the post office was closed, and rural deliveries were split between the Wheaton and Bartlett stations.

Across from Tedrahn's, on the northwest corner of the intersection, was a tavern, and on the northeast corner was the old creamery, now converted to a gas station and repair shop. The remaining southeast corner was a vacant farmed field.

|

| The former Cloverdale Creamery, by the mid-1950s, had become a gas station and repair shop. It cost 25¢ to get them to light the acetylene (welding/cutting) torch. |

The local farmers were predominantly German Catholic—the Stark, Hahn, and Mueller families had settled in the area in the 1850s. Arriving from Bavaria, they purchased land from the original Irish Catholic settlers. In 1852 the Diocese of Chicago authorized the construction of a small wooden church, St. Stephens, near the home of a prominent sheep rancher on the township's southern border. St. Stephens continued in operation for over thirty years. But in 1887, with access to its property cut off by the construction of the Chicago Great Western Railway, the church was forced to close. Parishioners were redirected to St. Michael's parish in Wheaton, five miles south, and the old church was torn down. The salvaged wood from it was used to build St. Michael's school. Only the St. Stephens Cemetery remains.

In 1920 the Cloverdale area Catholic farmers petitioned the Catholic Diocese of Chicago, asking for a new church to be built on land donated by the Stark family adjacent to Cloverdale on Army Trail Road. Bishop (later Cardinal) Mundelein approved, and, in 1924, construction was completed. In addition to the sanctuary, the new complex included a three-room school attached to the main church building, a rectory, a cemetery, and a small convent for the Order of Saint Frances nuns who taught at the school. The new church was named St. Isidore for the patron saint of farmers.

In addition to the Catholic school, Bloomingdale Township had established a small, one-room public school for the community. The school was expanded to four classrooms during the suburban expansion in 1959.

As roads in the area were improved, farmers began to have other options for shipping their milk. Competing for milk supply, Dairies in Chicago would send large refrigerated trucks directly to the farms early in the morning. As the milk transportation business fell off, the depot in Cloverdale was closed in 1934. Cloverdale returned to a flag stop—eastbound only—for a single local train running between Chicago and Freeport.

More significantly impacting Cloverdale was the creation of a live-work subdivision just south of town along Gary Avenue. Carol Stream, a community, named after the crippled daughter of the developer, Jay Stream, began building homes in the late 1950s on land purchased from several local farmers. Improvements in road access to Chicago, the impact of blockbusting and white flight on the city, and the provision of new jobs in an industrial development created by Jay Stream caused the rapid growth. Incorporated as the Village of Carol Stream, its new boundaries included Cloverdale. (The Lost Towns of Illinois - Gretna, Illinois, article has more detail on the development of Carol Stream.)

With increasing population and changes in zoning, more competition developed for businesses in Cloverdale. The restaurant and tavern closed in the early '80s and were leveled after being destroyed by fire a few years later. The old creamery was abandoned and later torn down. The lumber yard became a storage facility and staging area for a construction firm.

Tedrahn's soldiered on, still owned by descendants of the original founder and open, as always, daily until 10 P.M. seven days a week. But in the mid-1980s, the development of the new Stratford Square Shopping Center, just north of Army Trail Road, required a major eastward relocation of Gary Avenue. Left in the backwater and now in competition with a new convenience store and gas station on the main road, they finally closed after 95 years of operation by the same family.

St. Isidore's, benefitting from the growing suburban Catholic population, significantly expanded their facility, adding classrooms and building a new church building and rectory. The original church building still stands, used as a chapel. The Cloverdale Public School, now District 93, has expanded to a modern facility on the original site.

As Carol Stream expanded, the local land, once thought to be the most fertile in Illinois, became too valuable for framing. Most local farm families arranged land swaps, trading their Cloverdale farms for larger acreages further west in Illinois and Iowa.

Comment from the Author:

I grew up in Cloverdale in the 1940s and 50s. I was an altar boy at St. Isidore's and took my first communion there before leaving the area. My years living in the rural Cloverdale area were some of the happiest in my life. But in 1959, Jay Stream made my father a cash offer for our farm, one of the smaller ones in the area, that my Dad just couldn't refuse. He left farming, and we left Cloverdale a year later. Ironically, although virtually everything else has been changed, leveled, and redeveloped, our old house is still standing. My memories of eating orange push-ups while sitting on the steps of Tedrahn's, maybe all that's left of the town….

By Ken Molinelli, amateur historian, storyteller, and former Cloverdale resident.

Edited by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

.jpg)