|

| Philo Carpenter (1805-1886) |

An earlier ancestor was William Carpenter, a pilgrim who came from Southampton, England, to Weymouth, Massachusetts, in 1638, on the ship Bevis (also known as the Bevis of Hampton, was a merchant sailing ship that brought "Emigrants" from England to New England).

In 1787, the family came to western Massachusetts than a wilderness, where Philo Carpenter was born in the town of Savoy, February 27, 1805, the fifth of eight children of Abel Carpenter.

Philo lived on the farm with his father until he was of age. He received little money from his parents but did receive those greater gifts, a good constitution, a typical school education — supplemented by a few terms at the academy at South Adams — and habits of morality, industry, and economy. He made two trips as a commercial traveler as far south as Richmond, Virginia. He acquired an interest in medical studies during his stay at South Adams — traveled to Troy, New York — and entered the drug store of Amatus Robbins. In connection with a clerkship, he continued his studies and eventually gained a half interest in the business. He was married there in May of 1830 to Sarah Forbes Bridges, but she died the following November.

He closed out his business early in the summer of 1832. He shipped a stock of drugs and medicines to Fort Dearborn. The journey to Chicago was arduous. He took the short railroad then built to Schenectady, then took passage on a line boat on the Erie Canal to Buffalo, then on the small steamer Enterprise, Captain Augustus Walker, to Detroit, then by mud-wagon, called a stage, to Niles, Michigan, then on a lighter belonging to Hiram Wheeler, afterward a well-known merchant of Chicago, to St. Joseph at the mouth of the river, in company with George W. Snow. They had expected to sail in a schooner to Fort Dearborn, but on account of the report of cholera among the troops there, a captain, one Carver, refused to sail and had tied up his vessel. They, however, engaged two Indians to tow them around the head of the lake in a canoe with an elm-bark tow rope. At Calumet, one of the Indians was afflicted with cholera, but they kept on until they were within sight of the fort when the Indians refused to proceed. Samuel Ellis lived there and had come from Berkshire County, Massachusetts. They spent the night with him, and he brought them the following day in an ox wagon to Fort Dearborn on July 18, 1832.

There were less than two hundred inhabitants, mainly Indians and half-breeds, who lived in poor log houses built on both sides of the Chicago River near its mouth.

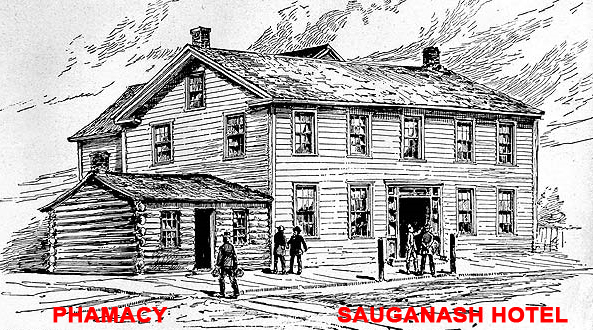

When Mr. Carpenter's goods arrived, he opened the first drug store in a log building on Lake Street, next to the Sauganash Hotel, near the Chicago River, where there was a great demand for his drugs, especially his quinine.

|

| The log building where Philo Carpenter opened his drug store next to the Sauganash Hotel (small log cabin on the left). Mark Beaubien opened the Eagle Exchange Tavern in 1829. In 1831, Beaubien added the frame structure and opened the Sauganash Hotel, Chicago's first grocery [EXPLANATION], hotel and restaurant at Wolf Point, on the east bank of the south branch of the Chicago River at the "forks," where the north and south branches meet. |

The anticipated opening of the Illinois-and-Michigan Canal, a bill for which, introduced by the late Gurdon S. Hubbard, passed the Illinois House of Representatives in 1833 — though it did not become a law till 1835, and the canal was not actually commenced until Mr. Hubbard removed one of the first shovelfuls of dirt, July 4, 1836 — turned attention to Fort Dearborn, increased the population rapidly, and Mr. Carpenter's business prospered.

|

| This sketch looks South-East at George Washington Dole's store on the South-West corner of Dearborn and South Water Streets, opposite the Beaubien store in Chicago. It was built in the summer of 1832. This was the first forwarding and commission house in Chicago. In the fall of 1832, Dole butchered and packed 150 cattle and 138 hogs for Oliver Newberry of Detroit. The cattle were bought from Charles Reed of Hickory Creek, and the hogs were purchased from John Blackstone, who drove them from the Wabash Valley. This is the first record of the packing industry, which turned out to be so important to Chicago. |

|

| A 6-Horse Team pulling a prairie schooner. |

|

| Courthouse Square on LaSalle between Washington and Randolph Sts., Chicago. |

The decision to expand his inventory was partially prompted by the fact that a second drugstore had been opened by Peter Pruyne. The small town of Chicago simply couldn't support two establishments dealing exclusively in drugs.

Another important consideration was the commonly accepted exchange system known as "store pay." Farmers coming into town would trade their produce for supplies; the storekeepers would, in turn, sell these goods to the townspeople. If a merchant didn't wish to participate in this moneyless trading system, he simply had to run his business on credit.

In 1842 he moved his drug store once again to 143 Lake Street, where it was known as the "Checkered Drug Store." Approximately two years later, he sold his pharmacy to Dr. John Brinckerhoff, abandoning his profession so that he could more carefully manage the real estate holdings he had amassed through the years. Some store fixtures were thought to have remained in use until consumed in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

Early on, Carpenter acquired a quarter-section ten miles up the north branch of the Chicago River.

A generous and trusting man, he made several endorsements for friends during his early years in Chicago. When the debts came to maturity, and the "friends" failed to pay their creditors, Carpenter was forced to borrow money to pay off some debts. The timing was poor, and in the financial panic of 1837, Carpenter owed some $8,600. His creditors demanded immediate payment. Since no cash was to be had, Carpenter prepared a schedule of his real estate holdings and submitted it to an impartial committee so they might choose those pieces of land that would most equitably serve to dissolve his financial obligations. The lands given in payment of his debts are valued today at over $29,705,625! Carpenter's only complaint about this arrangement was that, of all the lands from which to choose, I should have thought they might have left me my home." This was, however, only a temporary setback, for Carpenter's investment skill enabled him to rebuild his fortune, establishing a multi-million dollar estate in his later years.

Carpenter later purchased a quarter-section on the west side, considered undesirable because it was wetlands most of the year. He later subdivided the land into "Carpenter's Addition" parcels to Chicago.

It is that part of the west side bounded by Kinzie Street on the north, Halsted on the east, Madison Street on the south, and a line between Elizabeth Street and Ann Street on the west. (Philo Carpenter named Ann Street after his wife. It's Racine Avenue today.)

He ran for Mayor of Chicago twice on the Liberty Party ticket, losing to John Putnam Chapin in 1846 and James Curtiss in 1847.

Carpenter was known to have been a generous supporter of the Chicago Historical Society.

Carpenter Street (1032 West) in Chicago is named for Philo Carpenter, as was the public elementary school on Erie Street at Racine Avenue. In 1886 he donated $1,000 to establish a fund for the benefit of the first Carpenter School on the same site, just east of where the modern Carpenter Elementary School opened in 1957 and was closed in 2013. One of his daughters, Augusta Carpenter, is the namesake of Chicago's Augusta Boulevard.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

[1] Malaria was a common disease in Chicagoland and southern Illinois in pioneer days, wherever swamps, ponds, and wet bottomlands allowed mosquitoes to thrive; the illness was called ague, or bilious fever, when liver function became impaired; medical historians believe that the disease came from Europe with early explorers around 1500; early travel accounts and letters from the Midwest reports of the ague (a fever or shivering fit), such as those of Jerry Church and Roland Tinkham, the details of which are extracted from their writings:

From the Journal of Jerry Church, when he had "A Touch of the Ague" in 1830: ...and the next place we came to of any importance was the River Raisin, in Michigan. There we met with several gentlemen from different parts of the world, speculators in land and town lots and cities, all made out on paper, and prices set at one and two hundred dollars per lot, right in the woods and musquitoes and gallinippers thick enough to darken the sun. I recollect the first time I slept at the hotel; I told the landlord the following day I could not stay in that room again unless he could furnish a boy to fight the flies, for I was tired out myself, and not only that, but I had lost at least half a pint of blood. The landlord said he would remove the mosquitoes the next night with smoke. He did so, and after that, I was not troubled so much by them. We stayed there a few days, but they held the property so high that we did not purchase any. The River Raisin is a small stream of water, similar to what the Yankees call a brook. I was very much disappointed in the appearance of the country when I arrived there, for I anticipated finding something great and did not know but that I might on the River Raisin find the article growing on trees! But it was all a mistake, for it was rather a poor section of the country. ...We then passed on to Chicago, and there I left my fair lady traveler and her brother and steered my course for Ottawa in Lasalle, Illinois. Arrived there, I put up at the widow Pembrook's, near the town, and intended to make her house my home for some time.

I kept trading round in the neighborhood for some time and, at last, was taken with a violent chill and fever, and had to make my bed at the widow's, send for a doctor, and commence taking medicine, but it all did not do me much good. I kept getting weaker every day, and after I had eaten up all the doctor stuff the old doctor had, he told me that it was a very stubborn case, and he did not know if he could remove it and thought it best to have counsel. So I sent for another doctor, and they both attended me for some time. I kept getting worse and became so delirious as not knowing anything for fifteen hours. I, at last, came to and felt relieved. After that, I began to feel better and concluded that I would not take any more medicine, and I told my landlady what I had resolved. She said that I would surely die if I did not follow the doctor's directions. I told her I could not help it, that all they would have to do was bury me, for my mind was made up. In a few days, I began to gain strength, and in a short time, I got so that I could walkabout. I then concluded that the quicker I could get out of those "Diggins," the better it would be for me. So I told my landlady that I intended to take my horse and wagon and try to get to St. Louis; for I did not think I could live long in that country, I concluded I must go further south. I accordingly had my trunk re-packed and made a move. I did not travel far in a day but arrived at St. Louis, very feeble and weak, and did not care much how the world went then. However, I thought I had better try and live as long as possible.

From a letter by Roland Tinkham, a relative of Gurdon. S. Hubbard, describing his observations of malaria during a trip to Chicago in the summer of 1831: ...the fact cannot be controverted that on the streams and wet places, the water and air are unwholesome, and the people are sickly. It is not so bad in the villages and thickly settled areas, but it is a fact that in the country where we traveled the last 200 miles, more than one-half the people are sick; I know, for I have seen it. We called at almost every house, as they are not very near together, but still, there is no doubt that this is an uncommonly sickly season. The sickness is not often fatal; ague and fever, chill and fever, as they term it, and in some cases, bilious fever are the prevailing diseases.

From a letter by Roland Tinkham, a relative of Gurdon. S. Hubbard, describing his observations of malaria during a trip to Chicago in the summer of 1831: ...the fact cannot be controverted that on the streams and wet places, the water and air are unwholesome, and the people are sickly. It is not so bad in the villages and thickly settled areas, but it is a fact that in the country where we traveled the last 200 miles, more than one-half the people are sick; I know, for I have seen it. We called at almost every house, as they are not very near together, but still, there is no doubt that this is an uncommonly sickly season. The sickness is not often fatal; ague and fever, chill and fever, as they term it, and in some cases, bilious fever are the prevailing diseases.