Fritz thought about how to expand his operation. Upon learning that a local newspaper was giving away gasoline-powered miniature cars to children as subscription premiums, he noted the names and addresses of the individual winners. He soon followed up with offers to purchase the miniature cars. These became an additional attraction, along with the increasingly popular Pony Rides.

By the mid-30s, Fritz had named his little park "Kiddieland." This was before the Kiddieland name was used for amusement parks for young children. It was the first known use of the name "Kiddieland." However, his attempt to register the trademark failed, and the name eventually was used generically about the type of Park he envisioned - an amusement park with rides geared primarily toward children by the nature of their size and the speed and action of the mechanical rides. Fritz set standards for operating a safe, friendly, good-valued and clean amusement park.

Art Fritz has been credited with "launching a whole new development in the outdoor amusement industry." By 1940, Fritz had added the German Carousel, two Miniature Steam Locomotives, the Little Auto Ride, the Roto Whip in 1938, and a Ferris Wheel in 1940.

The 1940s brought the era of World War II and, as one might expect, delayed further growth and development at Kiddieland until the post-war years. Still, Fritz believed parents always found a way to bring their children out to the Park to make some memories and escape their problems of the day.

|

| From a 23-year employee: "The length of the ride depended on the air temperature. The Park was only open on Saturdays and Sundays early in the season. On Saturday morning, oil was applied to the track with a light rust coating. The ride was over 2 minutes with cool temperatures because the oil thickened. In July, when the Park was open 7 days a week in 90° temperatures the ride took only 37 seconds!" |

The Little Dipper was a light-hearted, breezy ride through a figure eight-track. The train tackled curvy descents and swift turns, racing at moderate speeds, making riders scream and giggle simultaneously. The car chugged through a whirlwind 700-foot-long track in about a minute. From a peak height of only 30 feet, the first drop wasn't too steep but was still exciting enough for a bit of tummy tickle. The quick swoops, fast curves, and sudden switchbacks were jaw-dropping.

Six Flags Great America in Gurnee, Illinois, salvaged the "Little Dipper" from Kiddieland in Melrose Park when it closed in 2009. The video below shows its twin sister, now operating in an amusement park in Marshall, Wisconsin.

VIDEOS

Take a ride on the "Little Dipper" roller coaster. This is the twin sister of Kiddieland's Little Dipper that was first in Kiddy Town at Harlem and Irving Park Road from 1953-1964. Then Hillcrest (Amusement) Park in Lemont bought the Little Dipper and it was running for their 1967 season. A small amusement park in Wisconsin called Little Amerricka Amusement Park (formerly Little A-Merrick-A) in Marshall, Wisconsin (owned by a family named Merrick). The Little Amerricka Amusement Park is still open. The "Little Dipper" was renamed the "Meteor" and was operational for the 2007 season. Videos by David Ellis.

Ride the "Meteor" (Little Dipper) in the first-person view

in this video by David Ellis.

in this video by David Ellis.

Ride the Little Dipper in the first-person view

in this video by David Ellis.

Ride the Little Dipper in the first-person view

in this video by David Ellis.

By 1950, Fritz expanded his dream of the perfect place for families to bring their children to have fun and laugh. Seven kiddie rides were added to the Park; the Merry-Go-Round, a hand-carved wooden carousel that greeted guests as they entered the Park, and the Little Dipper, a small wooden roller coaster, one of only two in the U.S. There were several maintenance and storage buildings constructed as well.

By this time, Fritz's daughters and their spouses, the second generation, were well involved in the Park's operation, and the Park's growth and development continued throughout the 1950s. Some existing rides were replaced with others.

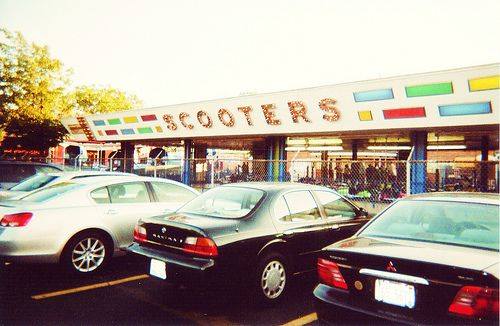

In 1962, the original Pony Ring was removed, the Scooters were installed in its place, and significant additional expansion to the Park was made. By the late 60s, several thrill rides were purchased to appeal to older children and teenagers. Kiddieland was beginning its evolution into a family amusement park. At this time, Kiddieland was operating with about 20 rides and attractions. In 1967, Fritz died unexpectedly before he saw the Polyp, the last ride he purchased, installed and running at Kiddieland.

Grandma Fritz (Anne) and the second generation continued to operate the Park for the next ten years. Fritz's third-generation grandchildren were also involved in the Park's operation then.

In 1977, Kiddieland was purchased by three of Fritz's grandchildren and their spouses. Two of these families and their children, the fourth generation, were the Park's last owners/operators. The late '70s marked a change in the vision of Kiddieland's future. The growth and development were in the direction of "Fun for the Entire Family." Additions in 1978 and 79 included a game building and the Mushroom Ride.

Early in the 1980s, park growth and development continued with the addition of the ever-popular Race-A-Bouts gasoline-powered antique car ride that intertwined with the north loop of the train tracks and encompassed two small ponds. The original game building added in 1978 was replaced with a larger, more accessible building, and the Volcano Play Center was designed and built. This area was a play area designed to help enhance a child's motor skills with net climbs, a ball crawl, tube slides, and a kid-powered Raft Ride. These elements were built into and around a scaled-down realistic replica of a volcano and also included one of the most remembered and mentioned Kiddieland rides, the Hand Cars. The last significant addition to the Park in the 80s was the Galleon, a high-swinging, brightly lit pirate ship installed in 1986. Late in 1987, Anne Fritz, the wife of Kiddieland's founder, died.

In the spring of 1995, some reshuffling was done to accommodate guests' wishes for a bigger, better place to eat in the Park. The Sky Fighter and the Umbrella Ride were relocated to the previously used area by the miniature gasoline-powered Tractors to make room for a new Food Court. At the same time, other renovations included rebuilding the old Popcorn Stand into an all-new Pizza Stand and rebuilding the old front game building so that it now houses the Water Race Game & Can Alley Games along with the Guest Services booth.

|

| Among its attractions was a fire engine, which was used to pick up birthday party guests at their homes and deliver them to the amusement park. |

In 2004, a dispute developed between Shirley and Glenn Rynes, who owned the land that Kiddieland occupies, and Ronald Rynes, Jr. and Cathy and Tom Norini, who owned the amusement park. The landowners sued the park owners, claiming that the Park had an improper insurance policy and that fireworks were prohibited in the lease. The case was thrown out in a Cook County court and later in an appeals court.

In 2008, the Kiddie Swing ride was installed at the entrance to the Volcano Play Center next to the Dip' N Drop.

The landowners declined to extend the lease on the land in early 2009, and Kiddieland closed at the end of the 2009 season. In late June 2010, it was announced that Kiddieland would be demolished. Kiddieland had over 30 rides and attractions and was Chicagoland's oldest family amusement park when it closed forever.

Kiddieland's Little Dipper roller coaster was bought by Six Flags Great America and is still in operation today.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

CLICK ON PHOTOS FOR A FULL-SIZE VIEW

|

| Photo by: Walter Rieger |

|

| Photo by: Walter Rieger |

|

| Six Flags Great America in Gurnee, Illinois, salvaged the "Little Dipper" from Kiddieland in Melrose Park when it closed in 2009. |

Visit our Souvenir Shop on your way out.