The beginning and growth of the theatre in Chicago followed a national pattern. The pattern's discoverer, Professor Douglas McDermott of California State College, Stanislaus, found that "once towns were established, theatre grew according to a three-phase process of transformation, which, because of its persistence, constitutes a working definition of frontier theatre in America."

McDermott described the first phase as "the theatre of the strolling player," which was composed of "magicians, variety performers, partners like Mark Twain's King and Duke, and small repertory companies made up of one or two families." Those companies performed in Lexington, Frankfort, Louisville, Cincinnati, and Pittsburgh as early as 1810. However, by the 1830s, cities such as Cleveland and Detroit had become part of a more complex second-phase circuit. In those companies, as many as twenty-four members performed in spaces specifically constructed as theatres.

Chicago's limited population and rugged climate, however, kept it in the first phase of American theatre until 1838. Charles Joseph Latrobe, who passed through the town in 1833, described it as "one chaos of mud, rubbish, and confusion." The lone itinerant performers of 1834 and the first band of strolling players in 1837 had to perform in what is euphemistically described in the modern period as a "found space." One hundred and fifty years ago, in Chicago, it was virtually the only space available: the local tavern.

|

This peaceful scene of Chicago in 1833 contrasts with Charles Joseph Latrobe's description of "one chaos of mud, rubbish, and confusion." Note the second Fort Dearborn on the south side of the Chicago River & John Kinzie's house on the north side of the river.

|

The first site of the Chicago Tavern Theatre was "the house of Mr. D. Graves," where on Monday, February 24, 1834, a Mr. Bowers — billed as "Professeur de tours Amusant" — gave a two-part presentation. The announcement of the performance appeared in the classified advertisements of the Chicago Democrat under "Exhibitions," and the act was described as follows:

FIRST PART

Mr. Bowers will fully personate Monsieur Chaubert, the celebrated Fire King, who so much astonished the people of Europe, and go through his outstanding Chemical Performance. He will draw a red-hot iron across his tongue, hands, etc., and will partake of a comfortable, warm supper by eating fireballs, burning sealing wax, live coals of fire, and melted lead. He will dip his fingers in melted lead and use a red-hot spoon to convey the same to his mouth.

SECOND PART

Mr. Bowers will introduce many very amusing feats of Ventriloquism and Legerdemain, many of which are original and too numerous to mention. Admittance 50¢, children half price.

Bowers is representative of the pioneers of the first wave of American theatre, about which McDermott writes: "Its members were amateurs with no particular theatrical background. ... They played in found spaces, such as barns, warehouses, courthouses, stores, and unfinished dwellings. Above all, they were itinerant, seldom remaining for more than one season in a region, and hardly ever visiting the same town twice."

Nothing is known about Bowers except that he performed a similar act in Cleveland a month before he arrived in Chicago. His program was not reviewed by the Chicago press, nor was he mentioned in the memoirs of other frontier performers. The circumstances of his performance, however, can be surmised from information about frontier Chicago.

At the time of Bowers's appearance, Chicago was a community of approximately 3,200 inhabitants. It was said to be "the largest commercial town in Illinois," with fifty-one stores, thirty general & dry goods stores, one bank, one newspaper, and ten taverns. The terrain, nevertheless, in the words of resident John Dean Caton, was "low wet prairie." So "impassable" were the roads, according to Caton, that guests at a ball held one month before Bowers's performance could travel only "on lumber-wagons or ox-carts, or other similar heavy conveyance."

The tavern of Dexter Graves, later called the Mansion House, was newly enlarged in 1834. According to Chicago historian A.T. Andreas, in 1831, Graves had built "an unpretentious log tavern" east of the corner of Dearborn Street on the north side of Lake Street. By July 1833, Graves was ordering nails from merchant Philo Carpenter for a two-story frame addition. When Harriet N. Warren Dodson passed through the town in November 1833, she observed that the tavern was "nearly enclosed." And by December, members of the Board of Trustees of Chicago were meeting there.

The second story of Graves's house — often referred to as the "Assembly Room" — remained unfinished, although it was equipped with fireplaces at either end. Charles Fenno Hoffman, an eastern visitor, described the area in January 1834 as "a tolerably-sized dancing-room." He also observed that an "orchestra [stand] of unplanned boards was raised against the wall in the center of the room." Such a platform would have sufficed as a stage for Bowers. The fact that the managers of the ball held in February 1834 printed a total of 200 tickets supports Hoffman's claim that the room had a good capacity.

Tickets to Bowers's performance were "to be had at the bar," which typically functioned as the registration desk and lobby in an early nineteenth-century tavern. Adults were admitted to the candlelit performance for 50 cents, and children for 25 cents. Seats were "reserved for Ladies" in an attempt to provide for the comfort and convenience of the spectators. Thus, although Virginia Baxley, the wife of Fort Dearborn's commanding officer, was willing to attend balls at Graves's "Assembly-Room," newspaper advertisements of the 1830s treated the presence of women in the theatre as if it were a somewhat unexpected and felicitous occurrence.

Although Bowers's performance was the first recorded theatrical event in Chicago, other forms of entertainment were available in the town's early period. Charles Butler, a real estate speculator, wrote in his diary entry of August 5, 1833, of attending the "monthly concert." The musicians were probably members of the Chicago Academy of Sacred Music, which practiced every Friday night in the municipal courtroom under the leadership of George Davis. The account books of John Calhoun, Chicago's earliest printer, indicate that at least three balls were held each year during the 1832-1835 period. Also, an advertisement in the Chicago Democrat of June 11, 1834, informed patrons that tickets for an exhibition of ventriloquism at another tavern, the Travelers' Home, were available "at the usual places." "At the usual places" implies that by 1834, the selling of tickets had become common enough to have developed a traditional set of purchase sites, one of which was probably the bar of the Travelers' Home.

|

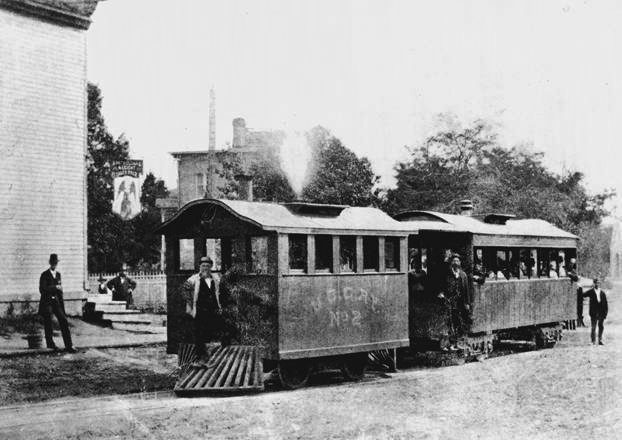

The bridge from the Travelers' Home / Wolf Point Tavern (at left) to the Miller Tavern was constructed in 1833

|

The Travelers' Home was originally and better known as the Wolf Point Tavern. Rechristened by its owner, Chester Ingersoll, in October 1833, it was a double log house built by James Kinzie, the son of early settler John Kinzie, a tavern on the west bank of the Chicago River at Wolf Point in 1828. The Green Tree Tavern & Inn was also built in 1833 and survived the 1871 Chicago Fire (read the article to find out how). If you are interested in what an overnight stay at the Green Tree Tavern & Inn was like in the early 1830s, click this link.

Henry H. Hurlbut, a Chicago historian writing in 1881, described its site as "a triangular point of ground embraced within the three streets, W. Lake, Canal, and W. Water Streets." The appearance of the building has been much debated, particularly because of a frequently reproduced engraving that first appeared in the Chicago Magazine in June 1857, and which Hurlbut described as a "hideous deformity." Eyewitness accounts agree, however, that by the summer of 1833, a second floor had been added. Guests slept in what one of its later owners, Mary Taylor, described as "the big unfinished room over the store." Mrs. Taylor's recollection that balls were held in that room creates the possibility that the ventriloquism performance of June 1834 was also held there, although the "spacious dining room" or "long room on the first floor" mentioned by early Chicago resident Leonora Hoyne would have been adequate. The Travelers' Home ventriloquist, a Mr. Kenworthy, like Bowers before him, was alone itinerant who performed "whims, Stories, Adventures, etc. of a Ventriloquist, as embodied in his entertaining monologue of the Bromback family." Kenworthy was apparently traveling east because he had performed in Columbia, Missouri, in February and was to surface in Cleveland in August. Unlike ventriloquists of later days, he worked without a dummy and instead threw his voice to various parts of the room.

The first major advance in Chicago theatre beyond the tavern level occurred in 1837 when an eastern scene painter and minor actor named Harry Isherwood converted the dining room of the old Sauganash Hotel into a performance site for Chicago's first theatrical company.

Like Dexter Graves's house and the Travelers' Home, the Sauganash Hotel, located on the southeast corner of Lake and Market streets, was the extension of a one-room log cabin. The cabin was eventually turned into a barroom. In 1831, a two-story frame addition — housing a dining room, sleeping rooms, and a second-floor parlor — was attached to the cabin's south side. Some twenty years later, Juliette Kinzie recalled the structure as a "pretentious white two-story building." In 1870, John Dean Caton remembered it as "a fashionable boardinghouse." But writing in 1833, Patrick Shirreff pictured the inn as "disagreeably crowded" and "dirty in the extreme." Charles Joseph Latrobe described it as a "vile two-storied barrack, which, dignified as usual by the title of Hotel, afforded us quarters." In it, he said, was "appalling confusion, filth, and racket."

By 1836, the Sauganash had changed hands and had been renamed the United States Hotel by its new proprietors, Harriet and John Murphy. Yet when Harry Isherwood began searching for a home for his theatre company in 1837, the building was deserted and available. In light of Harriet Murphy's comment that "we had no ballroom in our house but danced in the dining room," Andreas's contention that performances took place in the dining room is probably accurate.

Many of the descriptions of Chicago's first theatrical company and season require correction due to newspaper accounts from the Illinois State Historical Library, the American Antiquarian Society, and the University of Chicago. The seating capacity of the Sauganash, for example, has been inflated. In 1884, James McVicker contended that it seated 200; Andreas placed the capacity at about 300. Subsequent historians — including Bessie Louise Pierce, Milburn John Bergfield, and Ernestine and Harold Briggs — have accepted McVicker's figures. Yet contemporary newspapers state that when "upwards of 100 tickets" were sold, "the house was a complete jam."

The length of Chicago's first theatrical season, conversely, has been underestimated. Robert L. Sherman's Chicago Stage places the first performance of Isherwood's company on Monday, October 23, 1837; the Briggses and Gordon Van Kirk put the event "late in October." According to the Chicago American of October 21, 1837, however, the company had been performing for "nearly a fortnight," which would indicate an opening date shortly after October 7. There are similar problems with the closing date. Andreas claims that "it is known that the theatre was not kept open longer than six weeks,"; but contemporary newspapers show that Isherwood's company stayed in Chicago through the week of January 3, 1838 — nearly three months after the opening.

Finally, the extent of the company's repertoire and the level of its professionalism must be reevaluated. Douglas McDermott contends that the first-phase company "presented a repertoire of no more than a dozen of the established classics of the time." But contemporary sources indicate that at least thirty-four plays were presented by Isherwood during the 1837 season in Chicago.

McDermott has mistakenly placed the troupe into a phase of frontier theatre characterized by Mark Twain's King and Duke. But the troupe members organized by Harry Isherwood and his partner Alexander MacKenzie were not "amateurs with no particular theatrical background," as McDermott implies. They were seasoned performers. Their company was a professional offshoot of the Jefferson family troupe, which had begun operations in 1830 and disbanded in 1835. MacKenzie had been the partner of Joseph Jefferson II from 1832 to 1835 in Washington, Baltimore, and the Pennsylvania cities of York, Lancaster, Reading, and Pottsville.

The company that performed at Chicago's Sauganash Hotel in October 1837 had been formed in Buffalo, New York, in the spring of that year, when managerial problems, an actors' strike, and a lack of audience forced Edwin Dean and D. D. McKinney, operators of Buffalo's Eagle Street Theatre, to move their theatrical forces westward to the City Theatre of Detroit. On May 31, 1837, the company opened for its summer season, which lasted until September.

In early September 1837, Isherwood had set out for Cleveland, leaving the company to play a three-night engagement at the Detroit Museum. In Cleveland, he converted the Italian Hall into a theatre and announced a twelve-night season. The company opened on Tuesday, September 12, just three days after their last performance in Detroit. They had picked up several new actors, including a juvenile hornpipe dancer named Master Lavett (sometimes spelled Lavette). They remained in Cleveland until Tuesday, September 26.

Meanwhile, Isherwood proceeded westward, arriving in Chicago in late September or early October 1837. In the pelting rain, he wandered through town and finally found the Sauganash Hotel. Fifty years later, he wrote to McVicker: "It was a queer-looking place. It had been a rough tavern, with an extension of about fifty feet in length added to it. It stood at some distance out on the prairie, solitary and alone. I arranged with the owner and painted several pretty scenes."

The company that performed at Sauganash was managed by Isherwood and his partner, Alexander MacKenzie, a bookseller-turned-box-office-manager. At its nucleus were Isherwood and MacKenzie and the daughters of actor Joseph Jefferson I (1774-1832) — Hester Jefferson MacKenzie, wife of the partner, and Mary Anne Jefferson Ingersoll, a dancer/actress. Other members were William Childs, a comedian; Thomas Sankey, who specialized in playing elderly men; Madame Arreline, a "French" dancer who played the ingenue parts; and Henry Leicester, the leading man.

The company had ridden the steam packet Pennsylvania from Cleveland around the Great Lakes, docking at Green Bay, Wisconsin, two days before they arrived in Chicago. A French traveler, Count Francesco Arese, was among the passengers, and he described the troupe with patronizing humor:

There was also a theatrical company on its way to Chicago, whose two conspicuous members were the leading lady and the head dancer. Mrs. or Miss Ingerson, for I am not certain which, was neither young nor good-looking, but indeed quite the contrary; but to make up for that, she paced the deck with an air of as much importance as either Semiramis or Cleopatra could have worn. The dancer, who called herself French, or more truly advertised herself as French, had apparently had terrible misfortunes with her shoes, whether low or high, for she wore a pair of her husband's boots. Such was the slimness of her legs, which would have done credit to a fighting-cock (rooster), and the fullness of her dresses, that you might have called her a butterfly-in-boots.

The company landed in Chicago and began performing in the newly "fitted up" Sauganash shortly after October 7, 1837. It was not until October 17, however, that they applied to the Common Council for a six-month license, indicating their intention to stay during the winter. They requested that a low fee be set because they anticipated no profits due to a lengthy run. However, licensing fees were common and difficult to avoid during that period, and the Common Council established a fee of $150 for six months. Isherwood and MacKenzie protested the fee because their Buffalo license had cost only $50 for the year, and the expenses would be higher and the receipts lower in Chicago. The validity of their contention is shaky because license fees varied considerably in the period. In Detroit, the troupe of Dean and McKinney had paid $25 per week in May 1834, $12 per week in May 1835, and only $50 for the entire year in 1836. In 1839, Dean was to pay $100 for a six-month license in Buffalo. In 1838, John Miller was granted a permit for $5 per week to exhibit a circus in Chicago. And fees in the Kentucky towns of Lexington and Frankfort were already ranging from $30 to $40 per week. The Common Council of Chicago had not been unreasonable. Nevertheless, MacKenzie's and Isherwood's protests were shrewd business. City councils often reversed their initial decisions, and upon the motion of Alderman John Dean Caton, the term was changed to three months for $75. Isherwood and MacKenzie were paid on October 27, 1837.

The shortening of the theatrical term is significant. When the company left Chicago in January 1838, they stated that they wished to avoid "the severity of the weather," yet the decision may well have been influenced by the fact that their license had expired. They apparently had decided that renewal was unprofitable.

The fee was probably not a particular hardship, for it appears that the company's first season was reasonably successful. While there is no evidence for ticket prices charged in Chicago in 1837, Cleveland newspapers indicate that the MacKenzie-Isherwood troupe played there for 50¢ a ticket only a month before. Robert Sherman contends that the top ticket price in Chicago was 75¢. Although there is no way to verify Sherman's unfootnoted information, his use of specific play titles and cast lists suggests that he may have been working from scrapbook clippings that were destroyed after his death. Moreover, much of what he says dovetails with extant editorial comments. Consequently, it is safe to assume a ticket range of 50-75¢ for the 1837 Chicago season.

Given that range of prices, an audience capacity of approximately one hundred, and a run of seventy-nine performance days (excluding Sundays) from October 7, 1837, to January 6, 1838, the MacKenzie-Isherwood company could have played to approximately 7,900 people and taken in between $3,950 and $5,925. Editorial comments in newspapers during the season indicate that houses were excellent despite inclement weather. Moreover, the company returned for two more seasons and built its own theatre. Their objections to paying for a six-month license demonstrate that they had little expectation of filling the house in a town that first impressed Isherwood as "no place for a show."

Many of the pieces the MacKenzie-Isherwood company performed in Chicago were at least ten years old, while about one-third of them were the "most recent hits" of the last decade. Nearly all of the plays were English, and 68% of the titles that can be identified had been part of the Jefferson family's repertoire for fifteen years or more.

While the thirty-four plays known to have been performed in Chicago during MacKenzie-Isherwood's first season fall within the maximum of three dozen set by McDermott for a second-phase operation, they represent only 35% of the possible performance days. Consequently, the total repertoire is likely far more than McDermott's limit. The reason for that lies in the nature of a nineteenth-century theatrical company.

Nineteenth-century companies would organize, perform, break up, reform, and move on with a somewhat different constituency over and over again. A troupe such as the MacKenzie-Isherwood company was an assortment of actors, musicians, singers, and technicians whose professional and personal lives continually intersected. That explains why a small group of actors, such as the MacKenzie-Isherwood company, could produce what seems to the modern theatre practitioner an extraordinarily large number of plays in a short period of time. Their entire Chicago season was performed chiefly by six men and three women. However, their forces were occasionally augmented by such townspeople as Mr. and Mrs. George Davis, who were well known locally for their abilities in music and dance.

Although playing under less-than-ideal conditions, the MacKenzie-Isherwood company was essentially the vanguard of a more professional operation. They were not just passing through Chicago, as were Mr. Bowers or Mr. Kenworthy. They played three seasons in the city (October 1837-January 1838, May 1838-October 1838, and August 1839-November 1839), during which they made tours of Illinois, Iowa, and Minnesota. They were consciously attempting to establish a permanent theatrical base.

Moreover, they succeeded during their first season in nurturing a frontier audience. On Saturday, October 21, 1837, the Chicago American reported that "the acting is well spoken of and the crowded houses are constant." On Wednesday, November 8, the Chicago Democrat noted that "the audience is nightly increasing" and that the actors were frequently interrupted with "loud and protracted applause." On the twenty-second, the theatre was viewed as "flourishing in defiance of the embarrassment of the times" caused by the Panic of 1837. Women began to attend regularly in significant numbers. And despite torrential rains that began on November 21 and apparently continued through most of December, houses, according to the Democrat, were at least "respectable," if not full. When a benefit was held on December 17 for Henry Leicester, the company's leading man, the house was "a complete jam." By late December, Isherwood and MacKenzie had decided to build a theatre on the upper floor of a new building for the next season. Isherwood's prediction that Chicago was "no place for a show" had been wrong. In January 1838, when the performers embarked on a tour, they promised to return in the spring. Chicago's tavern theatre phase was over, and the city was about to advance to the next step of its theatrical history.

|

In 1857, Chicago showman James Hubert McVicker built his magnificent theatre on Madison Street between State and Dearborn Street. McVicker himself frequently performed in plays there. Other actors who appeared at this theatre were John Wilkes Booth and his brother Edwin Booth (who married McVicker's daughter Mary), Lotta Crabtree, Joseph Jefferson III, and Joseph K. Photograph from 1863.

NOTE: The sign on the building at the left reads, "Frank Munroes Green Room - Sands Pale Cream Ale." J.J. Sands’ “Columbian Brewery,” on the corner of Pine Street (N. Michigan Avenue) and E. Pearson Street, was built in 1855 and was a rival of Lill & Diversy Brewery, Chicago's first commercial brewery. Both breweries produced pale, or cream ale, and were leveled in 1871 by the Great Chicago Fire.

|

NOTE: The MacKenzie-Isherwood company produced at least 34 plays from October 1837 to January 1838. Compiled from "Chicago Stage" and the "Chicago Democrat Newspaper" for those months: The Hunchback, The Stranger, The Hypocrite, The Carpenter of Rouen, It is the Devil, The Dream at Sea, The Idiot Witness, Everybody's Husband, Demon of the Desert, The Polish Wife, Therese or The Orphan of Geneva, Ambrose Gumette, Pizarro or the Death of Rolla, Richard III, the Rendezvous, Othello, Charles II, The Deep Deep Sea or American Sea Serpent, Black-Eyed Susan, Raising the Wind, Perfection, A New Way to Pay Old Debts, No Song No Supper, William Tell, The Village Lawyer, Nature, and Philosophy, She Stoops to Conquer, Uncle Sam, The Rakes Progress, O Hush!, Popping the Question, The Weathercock, The Waterman. In addition, the pantomime Les Trois Amans was performed.

By Arthur W. Bloom, Ph.D.

Edited by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.