In historical writing and analysis, PRESENTISM introduces present-day ideas and perspectives into depictions or interpretations of the past. Presentism is a form of cultural bias that creates a distorted understanding of the subject matter. Reading modern notions of morality into the past is committing the error of presentism. Historical accounts are written by people and can be slanted, so I try my hardest to present fact-based and well-researched articles.

I present [PG-13] articles without regard to race, color, political party, or religious beliefs, including Atheism, national origin, citizenship status, gender, LGBTQ+ status, disability, military status, or educational level. What I present are facts — NOT Alternative Facts — about the subject. You won't find articles or readers' comments that spread rumors, lies, hateful statements, and people instigating arguments or fights.

- The use of old commonly used terms, disrespectful today, i.e., REDMAN or REDMEN, SAVAGES, and HALF-BREED are explained in this article.

- "NEGRO" was the term used until the mid-1960s.

- "BLACK" started being used in the mid-1960s.

- "AFRICAN-AMERICAN" [Afro-American] began usage in the late 1980s.

The Weekly Review presents herewith the first of a series of articles on the history of Beverly Hills, which are published through the courtesy of Mrs. Walter F. Heinnemann, 10423 S. Seeley Avenue.The seven articles appeared from October 29, to December 17, 1926. They were copied from the files the Weekly Review graciously made available and have been reproduced for the convenience of local residents.A sociological survey of Beverly Hills involves many problems peculiar to that community. Boundaries have shifted, are shifting today; the entire boundary line of the district has never been officially determined and can be given only according to the opinion prevailing at present.

|

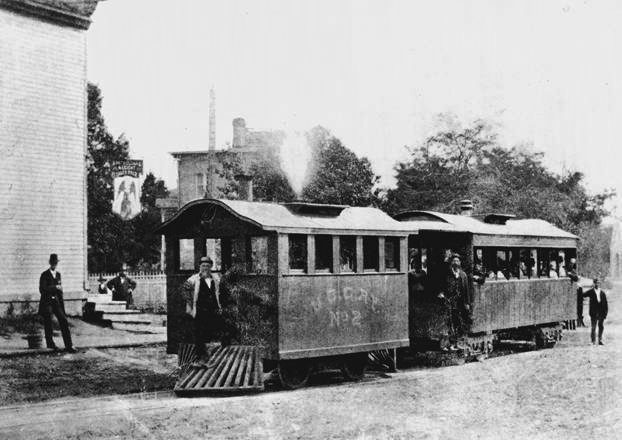

| There was a station or rather a platform on the south side of 99th Street near what is now Beverly Avenue and was then Oak Street. It was called the Oak Street station. Today's station. |

"Nearly south from this town and 12 miles distant is Blue Island, situated in the midst of an ocean of prairie. The name is peculiarly appropriate. It is a table of land about six miles in length and, on an average about two miles in breadth, of an oval form, rising suddenly some 30 or 40 feet high out of an immense plain that surrounds it on every side. The sides and slopes of the table, as well as a portion of the table itself, are covered with a handsome growth of timber, forming a belt surrounding about four or five thousand acres of prairie except a small opening at the south end. In summer, the plain is covered with prairie grasses and luxurious herbage. It is uninhabited, and when we visited it, from its stillness, loneliness, and quiet, we pronounced it a vast vegetable solitude. When viewed from a distance, Blue Island appears standing in an azure mist or vapor—hence the appellation 'Blue Island.'A map of Indian trails in the Chicago Historical Society shows that two trails—one from a portage trail from the mouth of the Calumet River to Lemont and Lockport, and another to Vincennes, Indiana passed through this region, crossing it at Washington Heights. From this crossing, the portage on or near the line of 103rd Street, about one-half mile, then deflected slightly to the south, probably to avoid a slough, crossed the island diagonally, going down the west slope where Mount Olivet Cemetery is. The Vincennes Trace followed the low ridges to the east of this table of land, crossing this island through the present site of the Village of Blue Island. The map also shows signal stations at both the north and south ends of the island and a village on Stony Creek just south of Blue Island. Arrowheads, hatchets, etc., found by those who first turned the sod in this vicinity, bear silent witness that the Indians were here. Evidence of fires and many Indian implements were found by E.A. Barnard on a sandy ridge that was on or near the portage as described above. The Potawatomi Indians met in the last great council with the whites, held near Chicago in the autumn of 1833, a few months before the description of Blue Island quoted above, was written, and signed away their last Illinois lands. The tribe of Potawatomi Indians was in the region until 1844, but the treaty devised by the U.S. government forced their removal to Kansas and Oklahoma. E. A. Barnard stood on the corner of 47th Street and Vincennes Avenue in 1847, saw the last of them in a train of 35 or 40 wagons pass by."

''For 25 years after that, occasional stories floated around of having seen an Indian who had returned to visit the home of his fathers.Probably the reporter for the Chicago Democrat drove out over the Vincennes road, the only well-established thoroughfare, the survey of which was completed in 1832 and its course marked by milestones, giving the distance to Vincennes. The course of this road from Gresham to Blue Island was not that of our present Vincennes road. From Gresham, it ran a little south of west diagonally to the Blue Island, striking it near 91st Street where it went uphill and ran along nearly south a little west of the grove skirting the east side of the island.There was a milestone on 115th Street on top of the hill and one on 123rd Street east of Western Avenue. It went downhill at the south end of the island, nearly at the same place as the present Western Avenue. Many of us remember a post · with a hand pointin9 east down 95th Street marked "To Chicago" where Robey Street (Damen Avenue) enters 95th Street from the north. This post was erected to turn travelers down the new town line road.The first white settler, De Witt Lane, built his log cabin in 1834, south of 103rd Street to the east of the grove, which bordered the island's west side. The same year Norman Rexford built a large log house in the northeast part of the island near 91st Street. He put up a sign "The Blue Island" and entertained travelers. Both of these first settlers soon moved. Mr. Lane sold his claim in 1836 for $1000 and moved to Lane's Island. Mr. Rexford moved out of our vicinity to the south end of the island.Jefferson Gardner built a house in 1836, which he built as a tavern. This house, although additions have greatly altered it, still stands (in 1926). My grandfather, Wilcox, bought this house, and his family moved into it in 1844. There were five other houses in the vicinity. The two log houses of 1834 are no longer occupied. The Pringle house where Mount Olivet Catholic Cemetery is, the Peck house near what is now the corner of 95th and Western, the Blackstone house near where the old Rexford tavern was. All of these were commodious frame houses. The Springhouse was a small house on the site of the Vanderpoel School and so-called because there was a natural spring of water there. A log house near where 95th Street goes downhill at the west side of the island completes the list for our neighborhood. The Village of Blue Island had a cluster of houses."

''Let us look at the present site of Tracy as it appeared then from the top of the hill, choosing a familiar spot, about where Mr. E. L. Roberts lived (the corner of 101st Street and Longwood Drive). The whole country was a common, covered with a growth of nature's sowing, the only exception being five or ten acres around each settler's home. From the point selected you may look north over an unbroken prairie and see in the distance the smoke hanging over Chicago, which then extended no further south than 12th Street (Twelfth '12th' Street was renamed Roosevelt Road on May 25, 1919). To the east, the view is quite unobstructed, as the ridges, which were covered with trees, had then only brush which the prairie fires kept so low that with very few exceptions, their tops rubbed against the shoulders of a man passing through. Looking south the view between the hill and the ridge where the Dummy Track ran, was a slough in which the waters seldom dried up even in midsummer, and the greater part of the season was difficult to cross. Conclusive of this fact it is stated, a sandhill crane, as late as in the 1860s, built her nest for several years between Uncle Erastus' house and the site of the Tracy depot (corner of S. Wood Street and 104th Streets), unmolested. No one would wade out after the eggs. Also, when he fenced his farm, the corner of Wood Street and Belmont Avenue was left without fencing, the water there is so deep that the cattle would not cross. Father told of driving, also, from here to Purington, Illinois on ice.

NOTE: Purington was a railroad station located 14.4 miles southwest of the La Salle Street Terminal of the Rock Island R.R. It was a station between Washington Heights at 12.0 miles and Blue Island-Vermont Street at 15.7 miles from Chicago. The Purington station was at 119th Street and S. Wood Street, {Geolocation: 41°40'38.9"N 87°39'58.6"W} that served the Purington-Kimbell Brick Company, and the small residential area serving employees the brick factory.

This slough was covered with a growth of coarse grass edged by high weeds. The weeds were the thickest for two or three rods just under the bluff, especially where the ravines poured their waters into the lowlands. Here, in autumn, wild artichokes, wild sunflowers, and ironweed waved their yellow flowers high above the heads of the tallest men, far surpassing in height the young oaks and hickories beyond. Their rank growth was attained during the summer when the immense swarms of flies kept the cattle away. When the frosts finally killed these insects, droves of cattle, from 50 to 100, entering them would be completely hidden from view in the high grass and weeds. Father tells of one day being in the weeds with a farm wagon and a yoke of oxen, having stepped a few rods (1 rod = 16.5 feet) away he could not find them again except by shouting to his brother, who had remained with the team. The ravine opposite Mr. Hauke's was known as Horse Thief Hollow. Here horse thieves utilized their friendly shade as a hiding place.

On the place just west of our present school house jointed bluegrass and pea vine grew together and were so dense and thickly interlaced that snakes ran along on the top of them.Where the fires had swept the ground clean of the coarse growths the more delicate varieties of prairie flowers, phlox, shooting stars, violets, etc., literally covered the earth with varied and beautiful flowers as the grass covers with green, a profusion of bloom of which we have no adequate conception. The orchid family was represented by several varieties of lady slippers, of which great masses showed their pink and white or yellow heads under the trees at the edge of the groves. Wild fruits were abundant. West Pullman was then a huckleberry patch. Wild strawberries grew thickest on the prairie east of Prospect. Aunt Mary tells of seeing the ground red with them at their place after her older brothers had mowed off the long grass with a scythe so she could find them. Blackberries were thick on almost all of the ridges. Plums were plenty. Hazelnuts were found, but the hickory trees were too small to bear the abundant supply which we enjoyed in our childhood.The nearest adjoining community was to the south, at Blue Island, where lived the Robinson, Rexford, Wattle, Jones, Wadham, and Brittan families and where Samuel Huntington, Mrs. Sutherland's father, came almost, if not quite, a half-century ago. Kyle's tavern, the old ten-mile house on Vincennes Road near Auburn, was the first house north. The nearest house east, situated a little west of a point where State Street strikes the ridge east of South Englewood, was occupied by a member of the great Smith family. The nearest schoolhouse was at Blue Island, where the Methodist circuit rider spoke on Sunday. The doctor came from Chicago.The Vincennes Road has been mentioned as on the hill, later travel followed the present line of Vincennes Road. Far away settlers in Indiana and Illinois carried their produce to market in Hoosier wagons, called prairie schooners, that is, wagons with white canvas covers. Long trains of these passed by from morning till evening, their numbers fully equal to that of the teams which now drive over the road. When nighttime came, their campfires glowed in the darkness. Near grandmother's house where they could enjoy the water from her excellent well was a favorite camping ground, and one of the diversions of the family was to visit the campers in the evening.Cattle, hogs, sheep, and occasionally turkeys drifted across the prairie in droves of from 100 to 500. In the fall thousands of these animals covered the prairies, for miles around the city as thick as they could be herded, in separate droves, waiting to get into the stockyards at 12th Street.The wild animals had not wholly disappeared, yet were greatly reduced in numbers. At night the howl of the wolf filled the air, but this occasioned no alarms. The game, such as prairie chickens, pigeons, quail, rabbits, squirrels, etc., were abundant and with guns and traps, the tables were well supplied. The only large game was the deer, the hunting of which afforded the most exciting sport. Preparatory to these hunts in the fall of the year it was the habit to burn off the prairie grass beyond the timbered ridges to the west. These fires were started and spread by a man mounted on horseback dragging a long burning rope saturated with turpentine through the dry grass. This left the prairie clear for the horses and hounds. The 'Morgan Boys,' as they were always called by my uncles, kept a pack of 25 or more greyhounds for deer hunting. Taking advantage of the fact that the deer would come to water then always found in the slough in this valley, the hunters would gather well-mounted on horseback, with their dogs and start the game to the west in a wild chase across the prairies. The strife among the hunters was to reach the game first and claim the horns as a trophy.Stagnant water and the breaking up of the new soil made prevalent the fever and ague. Many families still talk of all being sick at one time and of retiring to bed with a pitcher of water to quench the thirst which was sure to come and to which no one would be able to administer. Chills every day for a whole year were not infrequent experiences.Prairie fires were very frequent and much dreaded. I feel no account of the early days of Tracy would be complete without a prairie fire. In the afternoon of an autumn day of 1845, our family had their first experience with a prairie fire. Grandfather had died within the first few months of their residence here. The oldest son was sick in bed with the ague. Grandmother with her four younger sons and 14-year-old daughter went out to fight the flames, but Mary who was too small to help, remained at home, carrying water to her brother watching the fire. As she looked to the west and south she heard loud roaring and saw the flames running to 10 to 12 feet high where they reached the tall weeds and extending as far as she could see. Eagerly she watched the family who was fighting the flames. They had nothing with which to plow and they could only set backfires and whip it with wet bags and brush. They fought heroically but were continually obliged to retreat. Nearer and nearer the house it came, but at last, when it came to the low grass only a few rods from the door the fighters conquered. It was the custom to plow around the houses and stacks for protection against these fires. Sometimes two circles were plowed and the grass between them burned off, thus an effective barrier was made. Dr. Egan, one of the early doctors of Chicago, asked one of the farmers the best way to protect his stacks from fire and was told to plow around them and burn between. He followed the instructions by plowing several times around the stacks and then burning between them and the stacks, which resulted in his burning up his own hay.Someone has asked me to add a few words about the price of real estate. In 1836 Mr. Lane sold his pre-emption rights to 160 acres for $1000. As long ago as that real estate had its ebb and flow in prices. Soon after this real estate went down. The land around here was sold for $1.25 an acre and many said it was not worth that."

"In 1852 the Rock Island railroad was completed. A stagecoach route that had been passing through Blue Island since the late 1830s was discontinued. Trains stopped at Blue Island Village and at times a certain train stopped on signal at 95th Street. All produce was still hauled to Chicago in wagons. The line of the Vincennes road was altered and travel followed the new railroad. The drainage of the land by the railroad made this possible. In time the name followed the travelers, the road Commission formally gave the name Vincennes road to the new route.I can learn of not more than ten or twelve houses in 1852, about twice as many as bought in 1844. My father bought land and in 1851 built upon it. John Lynch had a home here. Reuben Smith lived on Western Avenue near 109th Street. Probably the first resident on the site of Morgan Park, William Betts, had a good house on 103rd Street on the West Side of the Island. I have not been able to learn the date when the town line roads were first used. Part of them—certainly 95th Street and Western Avenue—were used in 1852 or '53. A notice in the Chicago Democrat in July 1853, called for subscriptions to the stock for the new Plank road. This road was built beginning near 87th or 9lst Street on Western Avenue where the toll gate stood. It ran into the present Blue Island Avenue at 26th Street. This was the most direct route from Blue Island to Madison Street. It became a free road in the early 1860s.Timothy W. Lackore, fresh from the California goldfields, where he met with very moderate success, settled here in 1853, having bought the land on both sides of Western Avenue, extending some distance along the north side of 95th Street. The coming of the Lackore 1s was a notable event—there were so many of them who followed their leader, either that year or very soon. There were the three brothers, Timothy, Lemuel, and William, their three cousins, Luke Lackore and the Brightenballs, and Mullens, a cousin of Mrs. William Lackore and parents of Mrs. Timothy—eight families. Then they started things. Nat Mullen taught the first public school in the old spring house. Luke Lackore, a Methodist exhorter, led the first gathering for public worship in the Peck House, then owned and occupied by T. H. Lackore, built a blacksmith shop on the northwest corner of Western Avenue and 95th Street which he and Lemuel ran. Here you might see groups of men talking at a corner grocery (meaning of the word; grocery). The district school was discontinued and it was soon moved to a temporary structure about one-half mile west on 95th Street. On the north side of 95th Street, about two blocks east of Western Avenue there stood a row of poplar trees which were on the edge of the ground of the district school which was completed in 1856—the North Blue Island School. Luke Lackore continued to hold religious meetings, class meetings, etc., after the first one mentioned above and when the schoolhouse was finished, North Blue Island became a regular preaching station where a Methodist circuit rider held services once every two weeks.''

"By 1860 most of the land in this vicinity was fenced and tilled as farms. But considerable tracts, notably hundreds of acres owned by the Morgans, were neither tilled nor fenced, and the cattle of the community pastured in it freely. It is owing to these untilled acres that those of you who came in the 1870s and 1880s found so great an abundance and variety of wildflowers, especially the prairie flowers, as most of the farmers owning groves—the habitat of the wood flower, spared a part at least of the tract.The 1860s—the decade of the Civil War! When I was a very little girl, standing by my mother, her brother in a tense whisper said something in her ear. With a look of surprise, she said 'Another?' It was many years after before I learned what this might mean. A few times my uncle, going in the morning to the barn, found a fugitive slave lying in the hay of the manger where he could feel the warm breath of the cattle. I asked the aunt who told me this: Did the farmers have similar experiences? She replied 'I don't know, we never told—you didn't know which side they were on.'When Lincoln was a candidate for president there was held in the North Blue Island schoolhouse what was probably the first political meeting of the neighborhood. The torch-light procession came down the road giving invitation in song to 'Come and join the Wide Awakes, the Wide Awakes of Illinois,' feelings at the meeting ran high. Mr. Welch, a school teacher, and a democrat were asked to speak. But when he expressed views contrary to republican sentiments he was attacked and had no personal friends and men of fairer minds protected him, he might have been roughly handled. The attackers and defenders, struggling together, produced quite a melee.The call came for three months enlistments. In the Wilcox family were five sons. The two youngest enlisted. Returning at the end of this term they told the story of the reenlistment. Their company stood in line! The sign of reenlistment was a step forward—one after the other took the step—many hesitated. But finally all but one had taken the decisive step and when he finally came forward, wild cheering rent the air. The war went on, the two oldest sons enlisted, leaving the brother incapacitated for military service to care for the farm and their aging mother. One of these boys never returned and the other spent ten months in Andersonville Confederate army prison camp (aka Camp Sumter), in Georgia. This account of the Wilcox boys explains that the 'Wilcox Post' was the name of the local G.A.R. post. (The Grand Army of the Republic was a fraternal organization composed of veterans of the Union Army). Of the seven Morgan boys, several enlisted, and all returned. Erastus A. Barnard marched with Sherman to the Sea.

NOTE: The Rock Island R.R. (Chicago, Rock Island, and Pacific Railroad) and Panhandle (Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and St. Louis Railroad) lines intersected at what became known as “the crossing."

Several of the returning soldiers came home on the Panhandle; (Pittsburgh, Cincinnati and St. Louis railroad) line at 103rd and Vincennes, became known as ''The Crossing," which was completed in 1865 just before the close of the Civil War. This road ran an accommodation train stopping near its crossing with the Rock Island, and at Upwood, the name of the Morgan place. Commuter tickets were sold and it became possible to go to Chicago and back the same day for a day's shopping, visiting, or business, without the long tedious ride with horses.

Around the crossing of the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad and the Panhandle or "The Crossing" grew the nucleus of a settlement of the telegraph operator, station master, freight handlers, section hands, and a few others that were not railroad men, as a blacksmith, carpenter, mason, etc. In the early 1860s, three new schoolhouses were built which affected the North Blue Island school by taking part of the pupils. One was on the site of the Mount Greenwood School; one was down on Plank Road where now is the school at the corner of 79th Street and Western Avenue, a third near where the Washington Heights substation of the Chicago post office now stands. The North Blue Island school was still the meeting place on Sundays. For some years service had been held there on alternate Sundays by a Methodist circuit rider.

ln 1866 a revival came. For many evenings in the summer under the leadership of our pastor, Brother Close, meetings were held, farmers came after their day's work—two at least, from six or seven miles away. In the small schoolroom, dimly illuminated by candles brought for that purpose, the interest was intense. These meetings resulted in the formation of the North Blue Island Methodist Church. This church never had a resident pastor during its independent existence. Most of the preachers were Evanston students. They came down near the end of the week staying over Sunday with one of their parishioners, frequently calling on others, thus entering into real pastoral relations with their charges. The circuit, as I remember it, was North Blue Island, Lanes Island, and Black Oak. They preached in the morning at N.B.I. and on alternate Sunday afternoons at the other charges. Occasionally, when the presiding Elder came, three charges united in what was called a quarterly meeting.It is hard for you to realize how much the hearing of this Elder, who came from elsewhere, was anticipated by people who seldom heard any public speaker on any subject, except their own minister. The people of the visiting charges were entertained at dinner by the people of the neighborhood where the meeting was held. And this social intercourse was also highly valued. Sunday school was held in the summer in pleasant weather. There were no Christmas festivals, for there was no Sunday school held during the winter, but we had a few picnics, though not annually. One long remembered one which was called the 'Four horse picnic' because each wagon was drawn by four horses. We owed to a gift of used books from the First Presbyterian Church of Chicago that we had a really interesting library. A small case of books owned by the school district constituted the first circulating library of this vicinity.We had certain customs of our own. A few years ago the name of a man who used to attend that church was mentioned in my presence. I thought there was something odd about that man—what was it? Soon memory answered, he used to sit with his wife in church. We were strictly segregated in church, The men sat on one side, the women on the other. Occasionally a bride and groom sat together on their first appearance in church. In each of these instances the man did not embarrass himself by sitting on the women's side; she sat on the men's side.Persons going to The Crossing in the spring and summer of 1869 saw unwanted activities, new whitewashed fences, men clearing the underbrush from the grove, graders making streets. The explanation of all this was that the Blue Island Land Company had purchased a tract of land bounded, as nearly as our old maps show, on the west by Wood Street, between 99th and 107th Streets, extending east, north of 101st Street to Prospect and south of 101st Street the main Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific Railroad tracks at Prospect Avenue following the Grove was their principal street. There were miles of land vacant between here and Chicago, but this company had seen the beauty of these groves and ridges and was platting their ground for suburban lots. The Rock Island R.R. was making suburban life here possible by building the branch road to Blue Island. This branch left the mainline a little north of 99th Street, paralleled that street through part of its course, joining the track as it now is, a little south of 99th Street. The road was completed as far as the Panhandle; Pittsburgh, Cincinnati and St. Louis railroad tracks by the Fourth of July, 1869. On that day a great advertising picnic was held on the Ridge, east of the Panhandle between 95th and 99th, then unoccupied. Many trains ran out on the Panhandle; the Pittsburgh, Cincinnati and St. Louis Railroad and the Rock Island R.R. brought hundreds of people. There was picnicking in the grove—and military maneuvers given on the prairie just east of the grove."

NOTE: The abbreviation HR in the Christian clergy means 'His Reverence.'

NOTE: There is some argument about whether Beverly/Beverly Hills neighborhood is named after Beverly, Massachusetts, or Beverly Hills, California which was incorporated on January 28, 1914. It was named for Beverly Farms. It's often referred to as "Beverly Hills" because it sits on a glacial ridge that, at 672 feet, is the tallest natural point in Chicago.

No comments:

Post a Comment

The Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal™ is RATED PG-13. Please comment accordingly. Advertisements, spammers and scammers will be removed.