In historical writing and analysis, PRESENTISM introduces present-day ideas and perspectives into depictions or interpretations of the past. Presentism is a form of cultural bias that creates a distorted understanding of the subject matter. Reading modern notions of morality into the past is committing the error of presentism. Historical accounts are written by people and can be slanted, so I try my hardest to present fact-based and well-researched articles.

Facts don't require one's approval or acceptance.

I present [PG-13] articles without regard to race, color, political party, or religious beliefs, including Atheism, national origin, citizenship status, gender, LGBTQ+ status, disability, military status, or educational level. What I present are facts — NOT Alternative Facts — about the subject. You won't find articles or readers' comments that spread rumors, lies, hateful statements, and people instigating arguments or fights.

FOR HISTORICAL CLARITY

It’s a history that has been largely forgotten, even though some monumental physical traces remain. The 8th Illinois National Guard Regiment, which during the great war (WWI 1914-1918) came to be known as the 370th U.S. Infantry, was the only regiment in the entire United States Army that was called into service with almost a complete complement of Negro officers from the highest rank of Colonel to the lowest rank of Corporal. Yet few people know about this unit of young Negro men from Illinois who fought for a country that beat, lynched, and discriminated against them and people who looked like them.

The regiment reported at the various Illinois rendezvous on July 25, 1917, as follows:

The regiment reported at the various Illinois rendezvous on July 25, 1917, as follows:

“The American army didn’t want to have anything to do with them,” says Mario Tharpe, the director, writer, and producer of Fighting on Both Fronts: The Story of the 370th. Many Negro soldiers never saw combat, instead of being assigned positions as laborers. “Anthony Powell, a historian from San Jose, puts it well,” says Tharpe. “He says that for the Negro soldiers that came from down South, to join the army was leaving one hell to go to another form of hell, but one in which they wouldn’t be beaten or lynched.”

“The American army didn’t want to have anything to do with them,” says Mario Tharpe, the director, writer, and producer of Fighting on Both Fronts: The Story of the 370th. Many Negro soldiers never saw combat, instead of being assigned positions as laborers. “Anthony Powell, a historian from San Jose, puts it well,” says Tharpe. “He says that for the Negro soldiers that came from down South, to join the army was leaving one hell to go to another form of hell, but one in which they wouldn’t be beaten or lynched.”

In the face of such discrimination, both at home and at war, some of the soldiers in the 370th and other regiments that did fight in combat decided to stay in the more tolerant France after the war ended. During the war, Tharpe says, “The 369th and 370th brought jazz to Europe – they were known for having amazing jazz bands.” Some of the soldiers that made their home in France continued to share that American art form with Europeans, working as jazz musicians in the postwar period. France was not only more accepting but also more thankful than America: it awarded 71 Croix de Guerre medals to Negro soldiers before the United States offered any recognition of the honor.

Negro soldiers that returned to America found a country just as racist as before. In fact, the situation was in many ways worse. Many soldiers in the 370th were from the cultural hotbed Bronzeville neighborhood in the Douglas community of Chicago, which had swelled in population from the Great Migration. More people meant less economic opportunities for the returning soldiers, and also helped bring simmering racial tension in the city to a boil.

Soon after the 370th came home, the 1919 Chicago Race Riots broke out, resulting in the deaths of 38 people and the injury of hundreds more. Having fought to defend their country in Europe, Chicago Negro soldiers now fought to defend their community from hatred in their country. “These soldiers went off to war, where they knew they wouldn’t be respected, and represented Bronzeville,” Tharpe says. “They fought for rights and democracy by going to war, and then didn’t get justice or their due when they came home.”

Tharpe says that they therefore became the first wave of the Civil Rights movement, albeit a forgotten one. They advocated for recognition of their service in the war and eventually achieved it with the construction of the Victory Monument at 35th Street and King Drive.

Tharpe says that they therefore became the first wave of the Civil Rights movement, albeit a forgotten one. They advocated for recognition of their service in the war and eventually achieved it with the construction of the Victory Monument at 35th Street and King Drive.

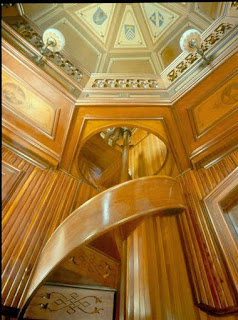

He did know that the nearby Eighth Regiment Armory, at 3533 S. Giles Avenue, had housed a Negro regiment, but that was about it. Before the war, the 370th had been the 8th Infantry Regiment of the Illinois National Guard, and the Armory was built for them in 1914. It now houses the Chicago Military Academy, a high school, and is listed both as a Chicago Landmark and on the National Register of Historic Places.

The Victory Monument and the Armory are the main physical remnants of the 370th. Few oral histories or photos survive. “People didn’t hold on to the memories of it because they didn’t realize the value,” says Tharpe. “Many people knew only that their father fought in the war, and that was it.” But the 370th’s significance and legacy live on.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

When I write about the INDIGENOUS PEOPLE, I follow this historical terminology:

- The use of old commonly used terms, disrespectful today, i.e., REDMAN or REDMEN, SAVAGES, and HALF-BREED are explained in this article.

Writing about AFRICAN-AMERICAN history, I follow these race terms:

- "NEGRO" was the term used until the mid-1960s.

- "BLACK" started being used in the mid-1960s.

- "AFRICAN-AMERICAN" [Afro-American] began usage in the late 1980s.

— PLEASE PRACTICE HISTORICISM —

THE INTERPRETATION OF THE PAST IN ITS OWN CONTEXT.

- At Chicago, Illinois-Headquarters, Headquarters Company, Machine Gun Company, Supply Company, Detachment Medical Department, and Companies A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and H.

- At Springfield, Illinois---Company I.

- At Peoria, Illinois---Company K.

- At Danville, Illinois---Company L.

- At Metropolis, Illinois---Company M.

|

| The French Croix de Guerre Medal |

Negro soldiers that returned to America found a country just as racist as before. In fact, the situation was in many ways worse. Many soldiers in the 370th were from the cultural hotbed Bronzeville neighborhood in the Douglas community of Chicago, which had swelled in population from the Great Migration. More people meant less economic opportunities for the returning soldiers, and also helped bring simmering racial tension in the city to a boil.

Soon after the 370th came home, the 1919 Chicago Race Riots broke out, resulting in the deaths of 38 people and the injury of hundreds more. Having fought to defend their country in Europe, Chicago Negro soldiers now fought to defend their community from hatred in their country. “These soldiers went off to war, where they knew they wouldn’t be respected, and represented Bronzeville,” Tharpe says. “They fought for rights and democracy by going to war, and then didn’t get justice or their due when they came home.”

sidebar

The 370th also fought in World War II (1939-1945).

But even that symbol has lost much of its significance. “Even though I lived in Bronzeville and drove past the Victory Monument nearly every day, I was absolutely not familiar with the 370th,” Tharpe says.

|

| Victory Monument at 35th Street and Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, Chicago. |

sidebar

The General Richard L. Jones Armory at 52nd Street and Cottage Grove Avenue is named for an officer of the 370th, General Jones, who managed both the Chicago Defender and the Chicago Bee Newspapers, and later was appointed U.S. Ambassador to Liberia.

|

| The General Richard L. Jones Armory at 52nd Street and Cottage Grove Avenue, Chicago |

VIDEO