In the winter months of 1903 there was a severe coal shortage in Chicago, Illinois.

It all began on May 12, 1902 when John Mitchell, who in 1898, at the age of 28, had become president of the United Mine Workers of America, pulled the miners in the anthracite fields of eastern Pennsylvania off the job. Firemen, engineers, and pump men followed on June 2nd, and within two weeks 147,000 workers had left the mines. Of these 30,000 abandoned the fields for good with 8,000 to 10,000 returning to Europe.

The strike finally ended on October 23, 1902 in a precedent-setting agreement, it being the first significant labor dispute in which the United States government intervened. It was such a significant event that toward the end of his career Samuel Gompers wrote, “Several times I have been asked what in my opinion was the most important single incident in the labor movement in the United States and I have invariably replied: the strike of the anthracite miners in Pennsylvania...from then on the miners became not merely human machines to produce coal but men and citizens.”

All that is significant today, but back in late 1902 all that mattered was that no hard coal was being mined for nearly a half-year at the time when cities should have been building up stockpiles in preparation for the long winter. Conditions deteriorated quickly once cold weather set in.

In Detroit on December 31st Mrs. W. T. Richardson, a boarding house keeper, entered the office of Stanley B. Smith & Co., a coal dealer, and pointed a revolver at the clerk on duty along with $7.50 and demanded a ton of coal after her son had failed to get the order earlier in the day. According to the Chicago Tribune the clerk “gazed down the blue barrel of the weapon and promptly produced the order.”

In early January the combination of a shortage of coal and a local teamsters’ strike forced officials at the Lincoln Park zoo to reduce heat in the animal and plant houses to save precious fuel. By January 4th less than a day’s supply remained. “After that,” The Tribune reported, “it is either coal or chills for the elephant, lions and other captives from the tropics.” The next day park workers were put to work cutting down dead trees in the park and stacking up the wood next to the zoo’s power house in case it became necessary to move from coal to wood.

By January 6th the Western Steel Car and Foundry Company in Hegewisch shut down, throwing 3,700 men out of work, because there was not enough coal to keep the machinery running.

On that same day Mrs. Margaret Perry and her three daughters died in a fire at the Hotel Somerset at Wabash and Twelfth Street. The Tribune began its coverage of the tragedy, “Had it not been for the high price and scarcity of fuel, Mrs. Margaret Perry and her three children, whose lives were sacrificed, would not have been in the hotel, as they left their home at 2535 Indiana avenue some time ago because they thought it would be cheaper to board than to attempt to heat their own apartments during the winter.”

On January 8th the Salvation Army began offering coal to the poor of the city at the rate of five cents for a 20-pound basket. The next day the situation in Toledo, Ohio had reached the point where a physician’s certificate authenticating the fact that there was illness in a home and that coal was necessary to safeguard the patient was required in order to buy a ton of coal.

As the middle of January approached the head of the Dunning Institution, home of the Cook County Insane Asylum, said that he would not be able to keep the buildings warm after 2 am on January 12th.

Even though a coal relief fund established by Mayor Carter Harrison had reached $2,976, casualties began to mount. Mrs. Esther Everett, 65, was found frozen to death in her bed at 3232 LaSalle Street. A six-month old baby died from exposure in an unheated home at 1341 S. Western Avenue. An unidentified man, between 65 and 70, was killed by a Lake Shore train while he was picking up coal on the tracks at Wood Street.

On January 10, 1903, Three hundred citizens of Arcola, Illinois stopped an Illinois Central train carrying 16 cars of coal to Chicago. An offer was made to buy the coal, but officials refused to sell it. At that point the mob, led by the pastor of the Presbyterian and Free Methodist churches, the presidents of both of the town’s banks, and a town policeman, confiscated the cars and the coal.

By January 19th things in Chicago had reached the point where the city council appropriated $25,000 to be used to distribute coal to the needy, asking the corporation counsel to investigate the legality of establishing a municipal coal yard.

Three days later 16-year-old William Stohmeyer went to the Chicago and Northwestern Railroad’s freight yard, carrying a sack to pick up coal that had fallen on the tracks. Martin J. Ward, a railway employee, fired at the boy, wounding him mortally. A crowd of 500 people soon gathered, and Ward ran to the yard office where he locked himself in the building. Police dispersed the crowd and freed Ward, who was then booked on suspicion of murder.

On February 2nd the Chicago began to sell coal from city yards in half-ton lots with orders being taken at the city’s pumping stations. A disgruntled coal dealer observed, “Amateurish mistakes have confused the mayor’s coal committee in its administration of the municipal coal yards... Instead of using simple methods the authorities started the most complex tactics imaginable, and now they are surprised to find themselves in a muddle.”

Less than two weeks later the city got out of the coal business. “The contractors have refused to send us any more coal to sell,” a Central Park station engineer explained.

Finally, a combination of warmer weather, an increasing supply, and more expeditious transportation ended the “coal famine” of 1903. Wherever the blame was placed, it did not hide the fact that real human beings suffered during that long winter of 1903.

In a February 3rd editorial, the Tribune observed philosophically that one day everyone would be short of coal because there would be no more left to mine. “Then nature will step in,” the opinion piece observed, “Nature is always ready for contingencies, and, supplemented by man’s ingenuity and skill, life probably will be as easy without coal or wood as it is with them, and certainly cleaner and healthier. ‘Star eyed science’ will not ‘waft us home the message of despair.’ It will find agencies in the sun, in the sea, and in the winds; and in the earth and in the atmosphere it will find unending supplies of that marvelous electric fluid of whose properties as a power in nature we still know but little.”

Chicago Tribune Article, January 12, 1903. - DEATHS CHARGED TO COAL FAMINE

Tuesday, March 14, 2017

The Chicago Coal Famine of 1903.

Living History of Illinois and Chicago®

Chicago,

Disasters,

Environmental,

Government

Sunday, March 12, 2017

Madison [County] Coal Corporation, Mine № 4, Glen Carbon, Illinois.

A strike went into effect on March of 1906. It was reported that over half a million workmen and their families were affected by a cessation of work. Locally it meant that 10 or 15 foreign-born citizens who worked in the mines made extended visits back to their homelands.

Since the strike appeared to be lengthy, the Madison Coal Corporation took 52 mules out of № 2 and № 4 mines. Since the mules had not been out of the mines for several years, citizens were amused to see the antics of the animals as they kicked up their heels in the enjoyment of the warm sunlight. Mining operations were abandoned at № 1 Mine around the turn of the century because of water seepage problems and Mine № 4 ceased operating in 1913.

Mine № 4 produced 3,577,993 tons of coal from 1893-1913.

Compiled by Neil Gale, Ph.D.

|

| Madison Coal Corporation, Mine № 4, Glen Carbon, Illinois. |

Mine № 4 produced 3,577,993 tons of coal from 1893-1913.

Compiled by Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Living History of Illinois and Chicago®

Civil Unrest,

IL West Central,

Illinois Business

The History of Lustron homes - many are still standing in Illinois. (1947-1950)

America won World War II, only to be confronted by a battle on the home front—the fight for housing. Soldiers and their stateside sweethearts had endured the war by dreaming idyllic dreams of postwar life, with happy families in new houses in a newly built suburb. Instead of white picket fences and handsome new homes, they had a profound housing crisis—the demand for housing outstripped the supply.

Their feeling of betrayal clouded the country's future. At the same time, the government had another problem: giant factories stood vacant, no longer needed for military production. How about retooling the factories to manufacture housing?

Their feeling of betrayal clouded the country's future. At the same time, the government had another problem: giant factories stood vacant, no longer needed for military production. How about retooling the factories to manufacture housing?

Lustron to the Rescue.

A factory-built house? The Lustron Corporation, a Chicago Vitreous Enamel Corporation division, was among the first to make this connection. The grand scale of the company's plans was awe-inspiring, and its product innovative: a thoroughly modern house with walls and a roof of porcelain-enamel steel panels.

But First, a Brief History of Prefabrication.

While a steel house was novel, the idea of mass-producing buildings was not. In 1801, British manufacturers began prefabricating cast-iron structural systems for industrial buildings. Within a few decades, factory-produced cast-iron storefronts became popular in American cities. By the early twentieth century, Sears, Roebuck and Company, Aladdin Homes, Harris Brothers Homes, and other merchants were selling kits for wood-frame houses out of catalogs.

As the century progressed, prefab entrepreneurs pushed the design envelope. By the mid-1930s, homebuyers could choose from nearly three dozen manufacturers featuring a dizzying array of materials: steel, precast concrete, asbestos cement, gypsum, and plywood. By the end of the decade, though, steel had fallen from favor because of problems with corrosion, condensation, insulation, and, most of all, the cost of the machines and facilities to fabricate the metal. The Lustron Corporation was to tackle these hurdles head-on.

First, though, World War II erupted, and the steel surpluses of the 1930s quickly became shortages as steel and other materials were dedicated to the war effort. Domestic housing construction virtually stopped, but the military forged ahead on the prefabrication frontier, developing structures that could be erected quickly without skilled tradesmen. While this effort led to technological advances, prefabrication emerged from the war with an image problem. "Whereas the prewar prefabricated house may have been suspect as an interesting freak," a Bemis Foundation study noted, "the postwar product was often stereotyped in the public mind as a dreary shack." Lustron's snappy porcelain-enamel panels helped dispel that image.

As well as a Brief History of Porcelain Enamel.

As well as a Brief History of Porcelain Enamel.

The use of this material, rather than the material itself, was innovative. The process of enameling metal sheets had been developed in Germany and Austria in the mid-1800s. Because porcelain enamel was tough, did not fade, and was easy to clean, it was quickly adopted by manufacturers of signs, appliances, and bathroom and kitchen fixtures. By the end of the nineteenth century, metal enameling was being done on an industrial scale in the United States. Iron was initially used for the base metal; sheets of low-carbon steel became available in the early twentieth century. A technological breakthrough during World War II used lower heat for the enameling process, which allowed manufacturers to use lighter-gage metal, lowering the price of the panels.

Chicago Vitreous Enamel Company.

Chicago Vitreous Enamel Company.

Porcelain enamel became famous for its style and substance. It perfectly suited the design sensibilities of the era, giving gas stations, hamburger stands (most famously White Castle), and other utilitarian structures a sleek, streamlined look.

The Porcelain Products Company, a subsidiary of the Chicago Vitreous Enamel Products Company, was a leading manufacturer of coated panels. Founded in 1919, Chicago Vit contributed to World War II by producing tank armor for turrets and commander domes.

The company hired Carl Strandlund, a Swedish-born engineer, inventor, and entrepreneur, to retool and run the plant for the war effort. His innovations dramatically sped up production, raising the company's and himself's national profile. He was soon promoted to executive vice President and general manager.

A Panel is Born.

A Panel is Born.

Towards the end of the war, Strandlund devised an architectural panel that was awarded patent number 2,416,240: "The present invention relates generally to architectural porcelain enamel panels, but more particularly to a novel and improved construction and an arrangement of interlocking and sealing adjacent porcelain enamel panels, units, or adjoining connecting parts of the exterior or interior walls of a building or structure of any type or design." Strandlund's seemingly unsexy panel was to be the building block of the Lustron house.

And then Lustron.

And then Lustron.

Right after the war, though, his first priority was manufacturing porcelain-enameled panels for gas stations until the bureaucracy in Washington denied him an allocation of steel. He informed us that housing was a higher priority, and he soon returned with a concept for an all-metal house, capturing the imagination of federal housing policy-makers. Lustron Houses were the idea of Illinois' businessman and inventor Carl Strandlund. In 1947, Strandlund established the Lustron Corporation and accepted the first of several multimillion-dollar loans from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) to get the production of Lustron houses underway.

"We believe that our technology has advanced to the point where a basic commodity as necessary as a home no longer should be handmade," Strandlund said. "We think it has advanced to the rank of the automobile-that it can be mass-produced, handled by local dealers, transported to a new locality if desired, even traded in on a larger model." He added: "The Lustron home isn't a cheap house by any means. It isn't a substitute for a house similar to those we are used to now. What Lustron offered was a new way of life."

A Home for Lustron.

Strandlund was allocated a former warplane manufacturing plant in Columbus, Ohio, for the Lustron factory. The massive plant contained over 1 million square feet of floor space and 22 football fields. It held some $15 million worth of special machinery and other industrial equipment, including 163 presses; the most colossal one could punch a bathtub from a sheet of steel in a single operation. The enormous scale required huge capital investment, including $37.5 million loaned by the RFC.

The first Lustron house was built in Columbus, Ohio, and it was unveiled to the public on October 16, 1948.

Demonstration Houses.

By April 1949, Lustron had over 100 "demonstration" houses strategically positioned in almost every major city east of the Rockies. Lustrons were sold through a network of builder dealers who covered a specific geographical area. In addition to erecting the house, builder-dealers were responsible for site preparation and the foundation slab, which were not included in the factory purchase price.

The erection process for the first Lustrons took up to 1,500 man-hours; later, the average was reduced to 350 hours, taking two weeks from start to finish. There were around 230 dealers in 35 states in Lustron's heyday, and the houses even made it as far as the Territory of Alaska and Venezuela.

You can usually spot a Lustron house by its distinctive roofs — which resemble the ones that came in Lincoln Log sets — and their luminous pastel exteriors: pink, surf blue, maize yellow, dove gray, and desert tan.

A Model Corporation.

Lustron ultimately offered eight commercial models, which varied in the number of bedrooms (two or three), size, and amenities. Color options for the semi-matte-finish exterior panels were surf blue, maize yellow, desert tan, and dove gray. Lustron "accessories" included screen doors, a storm-door insert, a combination storm-screen door, and storm windows, all in aluminum; steel Venetian blinds in ivory; a picture hanger kit; and an attic fan. The company encouraged homeowners to personalize their homes by screening in porches and adding breezeways. By 1949, Lustron was also selling garage panel packages. Unlike the house panels, which were part of a self-supporting structure, the garage panels had to be attached to a traditional wood-frame structure.

Lustron to the Rescue.

A factory-built house? The Lustron Corporation, a Chicago Vitreous Enamel Corporation division, was among the first to make this connection. The grand scale of the company's plans was awe-inspiring, and its product innovative: a thoroughly modern house with walls and a roof of porcelain-enamel steel panels.

But First, a Brief History of Prefabrication.

While a steel house was novel, the idea of mass-producing buildings was not. In 1801, British manufacturers began prefabricating cast-iron structural systems for industrial buildings. Within a few decades, factory-produced cast-iron storefronts became popular in American cities. By the early twentieth century, Sears, Roebuck and Company, Aladdin Homes, Harris Brothers Homes, and other merchants were selling kits for wood-frame houses out of catalogs.

As the century progressed, prefab entrepreneurs pushed the design envelope. By the mid-1930s, homebuyers could choose from nearly three dozen manufacturers featuring a dizzying array of materials: steel, precast concrete, asbestos cement, gypsum, and plywood. By the end of the decade, though, steel had fallen from favor because of problems with corrosion, condensation, insulation, and, most of all, the cost of the machines and facilities to fabricate the metal. The Lustron Corporation was to tackle these hurdles head-on.

First, though, World War II erupted, and the steel surpluses of the 1930s quickly became shortages as steel and other materials were dedicated to the war effort. Domestic housing construction virtually stopped, but the military forged ahead on the prefabrication frontier, developing structures that could be erected quickly without skilled tradesmen. While this effort led to technological advances, prefabrication emerged from the war with an image problem. "Whereas the prewar prefabricated house may have been suspect as an interesting freak," a Bemis Foundation study noted, "the postwar product was often stereotyped in the public mind as a dreary shack." Lustron's snappy porcelain-enamel panels helped dispel that image.

The use of this material, rather than the material itself, was innovative. The process of enameling metal sheets had been developed in Germany and Austria in the mid-1800s. Because porcelain enamel was tough, did not fade, and was easy to clean, it was quickly adopted by manufacturers of signs, appliances, and bathroom and kitchen fixtures. By the end of the nineteenth century, metal enameling was being done on an industrial scale in the United States. Iron was initially used for the base metal; sheets of low-carbon steel became available in the early twentieth century. A technological breakthrough during World War II used lower heat for the enameling process, which allowed manufacturers to use lighter-gage metal, lowering the price of the panels.

Porcelain enamel became famous for its style and substance. It perfectly suited the design sensibilities of the era, giving gas stations, hamburger stands (most famously White Castle), and other utilitarian structures a sleek, streamlined look.

The Porcelain Products Company, a subsidiary of the Chicago Vitreous Enamel Products Company, was a leading manufacturer of coated panels. Founded in 1919, Chicago Vit contributed to World War II by producing tank armor for turrets and commander domes.

The company hired Carl Strandlund, a Swedish-born engineer, inventor, and entrepreneur, to retool and run the plant for the war effort. His innovations dramatically sped up production, raising the company's and himself's national profile. He was soon promoted to executive vice President and general manager.

Towards the end of the war, Strandlund devised an architectural panel that was awarded patent number 2,416,240: "The present invention relates generally to architectural porcelain enamel panels, but more particularly to a novel and improved construction and an arrangement of interlocking and sealing adjacent porcelain enamel panels, units, or adjoining connecting parts of the exterior or interior walls of a building or structure of any type or design." Strandlund's seemingly unsexy panel was to be the building block of the Lustron house.

Right after the war, though, his first priority was manufacturing porcelain-enameled panels for gas stations until the bureaucracy in Washington denied him an allocation of steel. He informed us that housing was a higher priority, and he soon returned with a concept for an all-metal house, capturing the imagination of federal housing policy-makers. Lustron Houses were the idea of Illinois' businessman and inventor Carl Strandlund. In 1947, Strandlund established the Lustron Corporation and accepted the first of several multimillion-dollar loans from the Reconstruction Finance Corporation (RFC) to get the production of Lustron houses underway.

"We believe that our technology has advanced to the point where a basic commodity as necessary as a home no longer should be handmade," Strandlund said. "We think it has advanced to the rank of the automobile-that it can be mass-produced, handled by local dealers, transported to a new locality if desired, even traded in on a larger model." He added: "The Lustron home isn't a cheap house by any means. It isn't a substitute for a house similar to those we are used to now. What Lustron offered was a new way of life."

A Home for Lustron.

Strandlund was allocated a former warplane manufacturing plant in Columbus, Ohio, for the Lustron factory. The massive plant contained over 1 million square feet of floor space and 22 football fields. It held some $15 million worth of special machinery and other industrial equipment, including 163 presses; the most colossal one could punch a bathtub from a sheet of steel in a single operation. The enormous scale required huge capital investment, including $37.5 million loaned by the RFC.

The first Lustron house was built in Columbus, Ohio, and it was unveiled to the public on October 16, 1948.

Demonstration Houses.

By April 1949, Lustron had over 100 "demonstration" houses strategically positioned in almost every major city east of the Rockies. Lustrons were sold through a network of builder dealers who covered a specific geographical area. In addition to erecting the house, builder-dealers were responsible for site preparation and the foundation slab, which were not included in the factory purchase price.

The erection process for the first Lustrons took up to 1,500 man-hours; later, the average was reduced to 350 hours, taking two weeks from start to finish. There were around 230 dealers in 35 states in Lustron's heyday, and the houses even made it as far as the Territory of Alaska and Venezuela.

You can usually spot a Lustron house by its distinctive roofs — which resemble the ones that came in Lincoln Log sets — and their luminous pastel exteriors: pink, surf blue, maize yellow, dove gray, and desert tan.

|

| 600 North 74th Street, Belleville, Illinois. Photo: September 9, 2013. |

Lustron ultimately offered eight commercial models, which varied in the number of bedrooms (two or three), size, and amenities. Color options for the semi-matte-finish exterior panels were surf blue, maize yellow, desert tan, and dove gray. Lustron "accessories" included screen doors, a storm-door insert, a combination storm-screen door, and storm windows, all in aluminum; steel Venetian blinds in ivory; a picture hanger kit; and an attic fan. The company encouraged homeowners to personalize their homes by screening in porches and adding breezeways. By 1949, Lustron was also selling garage panel packages. Unlike the house panels, which were part of a self-supporting structure, the garage panels had to be attached to a traditional wood-frame structure.

sidebar

White Castles, incorporated in 1924, earliest restaurants were built using white brick and had nothing to do with Chicago's Water Tower. They were just supposed to look like a castle, but after the chain came to Chicago in 1928, Walter Anderson and Billy Ingram based the design of their first Chicago store on Chicago’s Water Tower, mimicking its crenellations and turrets in steel panels covered in white porcelain enamel tiles making it easy to clean and maintain.They designed a small, prefabricated steel building so that the chain could pack up and move a building after a property lease was up. The first White Castle in Chicago, № 35, was a steel castle built at 2501 East 79th Street. Anderson & Ingram's design built more than 300 White Castle restaurants throughout the 1920s. Only a few of the steel buildings are still standing, and none are White Castles anymore.

The Dream's Demise.

Overly optimistic promises, poor decision-making, and political chicanery brought on Lustron's demise. Strandlund's estimates of the plant's production levels proved far higher than was initially feasible. Not all of the factory's marvels turned out to be so marvelous: to be economical, for example, Lustron needed to sell about two-thirds of the output of the bathtub press to other companies. The tub, however, was a nonstandard size, making it virtually unmarketable.

The biggest problems, though, came from politics on both local and national levels. Building inspectors did not embrace the unfamiliar structural system and, with the encouragement of unions fearful of losing jobs, forbade the erection of Lustrons in some cities, including Chicago. Even more troublesome was an investigation by a U.S. Senate banking subcommittee into the RFC loans. This led, in 1950, to the loans being recalled, forcing the Lustron Corporation into bankruptcy and bringing the production line to a permanent halt by May.

Architect and MIT professor Carl Koch, who had worked briefly for Lustron on a deluxe model that was never produced, later reflected: "When I leaf back through the records, brochures, contracts, the transcript of Congressional autopsies-I admit to the confusion of feelings between the way we regarded it then... and the way it turned out to be. Seldom has there occurred a like mixture of idealism, greed, efficiency, stupidity, potential social good, and political evil. Seldom, surely, has a good idea come so close to realization and been so decisively slugged."

Strandlund's dream ended, but the Lustron legacy lives on. Although some of the approximately 2,680 Lustrons manufactured have succumbed to environmental and economic forces, perhaps as many as 2,000 survive and are being embraced by a new generation of homeowners who appreciate the special qualities of these unique houses.

Overly optimistic promises, poor decision-making, and political chicanery brought on Lustron's demise. Strandlund's estimates of the plant's production levels proved far higher than was initially feasible. Not all of the factory's marvels turned out to be so marvelous: to be economical, for example, Lustron needed to sell about two-thirds of the output of the bathtub press to other companies. The tub, however, was a nonstandard size, making it virtually unmarketable.

The biggest problems, though, came from politics on both local and national levels. Building inspectors did not embrace the unfamiliar structural system and, with the encouragement of unions fearful of losing jobs, forbade the erection of Lustrons in some cities, including Chicago. Even more troublesome was an investigation by a U.S. Senate banking subcommittee into the RFC loans. This led, in 1950, to the loans being recalled, forcing the Lustron Corporation into bankruptcy and bringing the production line to a permanent halt by May.

Architect and MIT professor Carl Koch, who had worked briefly for Lustron on a deluxe model that was never produced, later reflected: "When I leaf back through the records, brochures, contracts, the transcript of Congressional autopsies-I admit to the confusion of feelings between the way we regarded it then... and the way it turned out to be. Seldom has there occurred a like mixture of idealism, greed, efficiency, stupidity, potential social good, and political evil. Seldom, surely, has a good idea come so close to realization and been so decisively slugged."

Strandlund's dream ended, but the Lustron legacy lives on. Although some of the approximately 2,680 Lustrons manufactured have succumbed to environmental and economic forces, perhaps as many as 2,000 survive and are being embraced by a new generation of homeowners who appreciate the special qualities of these unique houses.

VIDEOS

Historic Lustron Home

The Thor washing machine/dishwasher combo!

BROCHURES

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Living History of Illinois and Chicago®

Famous,

Historic Buildings,

Inventors and Inventions,

Technology

Lake Park, Chicago, Illinois, later renamed to Grant Park.

Chicago's Lake Park was officially designated as a park on April 29, 1844. When the Illinois Central Railroad was built in Chicago in 1852, they were permitted to build a breakwater allowing the trains to enter along the lakefront on a causeway built offshore, just west of the breakwater.

The resulting lagoon between the man-made breakwater and the shoreline became a stagnant pool with unruly garbage and waste. The stench was so bad that the lagoon was filled in 1871 with rubbish and debris from the Great Chicago Fire.

In 1896 the city began extending Lake Park into the lake with additional landfill.

On October 9, 1901, Lake Park was renamed Grant Park in honor of Galena, Illinois resident, American Civil War General and United States President, Ulysses S. Grant.

|

| Click to view a full-size image. |

|

| Lake Park (now Grant Park), Chicago, 1885 |

|

| An 1868 Chicago Map showing the Illinois Central Railroad causeway. |

On October 9, 1901, Lake Park was renamed Grant Park in honor of Galena, Illinois resident, American Civil War General and United States President, Ulysses S. Grant.

Compiled by Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Living History of Illinois and Chicago®

Chicago,

Transportation

Saturday, March 11, 2017

The History of Chicago's President Street Names.

Anyone familiar with downtown Chicago knows the "President Street" names. This naming scheme is an old Chicago tradition, as with numerous other towns and cities around the country.

Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, Adams, Jackson, Van Buren, Harrison, Tyler, Polk, Taylor, Fillmore. Those are the first 13 presidents, in order, and 12 of them have streets in or near downtown named after them.

After Fillmore left office in 1853, the city seems to have abandoned the custom of automatically giving a president his own street. Then, Presidents had to earn this honor.

What about Pierce, Hayes, Arthur, Cleveland, and Harding? Those are Chicago Street names but not named for a former president.

When President Woodrow Wilson died in 1924, the city council decided he deserved a street. Chicago already had a Wilson Avenue, so the city council decided to change Western Avenue to "Woodrow Wilson Road." That lasted about a month until pressure from business owners brought back the old name in a hurry.

Since the Woodrow Wilson fiasco, Chicago has avoided the hassle of renaming streets to honor presidents. Eisenhower and Kennedy got expressways named after them. No address changes to worry about there! Except for the displaced residents and businesses.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, Adams, Jackson, Van Buren, Harrison, Tyler, Polk, Taylor, Fillmore. Those are the first 13 presidents, in order, and 12 of them have streets in or near downtown named after them.

Because there were two presidents named Adams, Quincy Street honors John Quincy Adams, president № 6.

Of course, I've saved the story of why a president was shunned from this time-tested honor for later in the article.

|

| Jackson Boulevard is named after Andrew Jackson, the 7th President of the United States. Franklin Street is named after Benjamin Franklin. |

From 1853 to 1909, out of eleven men who served as President, only four made the cut; Lincoln Avenue, Grant Place, Garfield Boulevard, and Roosevelt Road.

What about Pierce, Hayes, Arthur, Cleveland, and Harding? Those are Chicago Street names but not named for a former president.

When President Woodrow Wilson died in 1924, the city council decided he deserved a street. Chicago already had a Wilson Avenue, so the city council decided to change Western Avenue to "Woodrow Wilson Road." That lasted about a month until pressure from business owners brought back the old name in a hurry.

Since the Woodrow Wilson fiasco, Chicago has avoided the hassle of renaming streets to honor presidents. Eisenhower and Kennedy got expressways named after them. No address changes to worry about there! Except for the displaced residents and businesses.

William Howard Taft got an Avenue (access road) named after him in Franklin Park that goes into O'Hare Airport at the southernmost point (11600W-4200N-4400N). There are no buildings or structures on Taft Avenue.

The one President whose named street was quickly stripped from him is President № 10, John Tyler. When the first southern states seceded in 1861, Tyler led a compromise movement; failing, he worked to create the Southern Confederacy. He died in 1862 a member of the Confederate House of Representatives.

Tyler street was renamed later to Congress Street (Congress Parkway today).

The honorary street name program (brown signs) has been in place since 1964, when a stretch of LaSalle Street was designated "The Golden Mile" to honor the city's financial district.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Living History of Illinois and Chicago®

Chicago,

Government

Chicago's Western Avenue name was changed to Woodrow Wilson Road in 1924.

As any true Chicagoan knows, Western Avenue is the longest street in the city. Would you believe it was once named Woodrow Wilson Road?

Woodrow Wilson, 28th President of the United States, died on February 3, 1924. He’d been an icon of the Progressive movement and led the country through the First World War. The Chicago City Council wanted a suitable way to honor him.

It is not unusual for the City of Chicago to have streets named after U.S. Presidents, as the Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal™ article reports "The History of Chicago's President Street Names."

A few years after Theodore Roosevelt died, the aldermen changed 12th Street to Roosevelt Road. What was good for a dead Republican president should be good for a dead Democratic one.

Since the city already had Wilson Avenue (named after John P. Wilson, lawyer, and donator to Children's Memorial Hospital), it was decided to use President Wilson’s full name on his street.

It’s not clear why the lawmakers chose Western Avenue for renaming. On April 25, 1924, they voted to re-designated the street as Woodrow Wilson Road.

It’s not clear why the lawmakers chose Western Avenue for renaming. On April 25, 1924, they voted to re-designated the street as Woodrow Wilson Road.

On April 26, 1924, the Tribune dropped a bombshell on the people of Chicago, though the newspaper didn't play it as the 8-column banner lead nor even above the fold. In fact, the seven-line, one-paragraph item was hanging on to the bottom of the front page.

Back in 1924, Chicagoans were just angry about the change. They protested the change, petitioning their aldermen with hundreds of signatures. The Tribune seemed to wage its own silent protest by not using the new name in articles: automobiles still crashed, banks were still robbed and famous people still interacted with the public on a roadway called Western Avenue.

Aldermen appeared to have repealed the Wilson name sometime in June, about the same time Wilson supporters offered the alternative solution of renaming Municipal Pier after the recently deceased 28th president. That didn't fly either, of course; that honor went to the Navy.

The 12th street-to-Roosevelt Road change had caused little controversy. But now the property owners along Western Avenue objected to the expense involved in renaming their street. Within a few weeks, they’d gathered over 10,000 signatures asking that the old name be restored.

The Tribune sent its inquiring reporter to the corner of “Washington Boulevard and Woodrow Wilson Road” to gauge public opinion. Most people said the change didn’t make any difference to them. One young lady did say she favored the new name because “it sounds lots nicer, and we see enough old things around here.”

The property owners prevailed. Less than a month after its original action, the council ordered the street to change back to Western Avenue. A proposal to rename Navy Pier after Wilson went nowhere.

In 1927 the council changed Robey Street to Damen Avenue, despite resident protests. When Crawford Avenue was renamed Pulaski Road in 1933, that set off a battle that lasted 19 years before Pulaski was legally accepted. More recently, a proposal to change part of Evergreen Avenue to Algren Street was abandoned in the face of local resistance.

In the 1930s, the Chicago City College system came to the rescue with Woodrow Wilson Junior College. Even that didn't last: In 1969, the school was renamed Kennedy-King College after Robert F. Kennedy and Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Wilson Avenue on the North and Northwest sides is named after a different Wilson.

The lesson seems to be that changing a street name will always rub some people the wrong way and is a high cost for changes to maps and for businesses. That’s why the city came up with the idea of honorary streets in 1964.

Chicago designated its first honorary street name in 1964, declaring the section of LaSalle Street between Wacker Drive and Jackson Boulevard the "Golden Mile" to honor the city's financial clout. Over the next nearly two decades, only two more signs were designated, according to the Chicago Department of Transportation.

Compiled by Neil Gale, Ph.D.

|

| Northeast Corner of Devon Avenue and Woodrow Wilson Road, Chicago, Illinois. circa 1925. |

It is not unusual for the City of Chicago to have streets named after U.S. Presidents, as the Digital Research Library of Illinois History Journal™ article reports "The History of Chicago's President Street Names."

A few years after Theodore Roosevelt died, the aldermen changed 12th Street to Roosevelt Road. What was good for a dead Republican president should be good for a dead Democratic one.

Since the city already had Wilson Avenue (named after John P. Wilson, lawyer, and donator to Children's Memorial Hospital), it was decided to use President Wilson’s full name on his street.

On April 26, 1924, the Tribune dropped a bombshell on the people of Chicago, though the newspaper didn't play it as the 8-column banner lead nor even above the fold. In fact, the seven-line, one-paragraph item was hanging on to the bottom of the front page.

Back in 1924, Chicagoans were just angry about the change. They protested the change, petitioning their aldermen with hundreds of signatures. The Tribune seemed to wage its own silent protest by not using the new name in articles: automobiles still crashed, banks were still robbed and famous people still interacted with the public on a roadway called Western Avenue.

Aldermen appeared to have repealed the Wilson name sometime in June, about the same time Wilson supporters offered the alternative solution of renaming Municipal Pier after the recently deceased 28th president. That didn't fly either, of course; that honor went to the Navy.

The 12th street-to-Roosevelt Road change had caused little controversy. But now the property owners along Western Avenue objected to the expense involved in renaming their street. Within a few weeks, they’d gathered over 10,000 signatures asking that the old name be restored.

The Tribune sent its inquiring reporter to the corner of “Washington Boulevard and Woodrow Wilson Road” to gauge public opinion. Most people said the change didn’t make any difference to them. One young lady did say she favored the new name because “it sounds lots nicer, and we see enough old things around here.”

The property owners prevailed. Less than a month after its original action, the council ordered the street to change back to Western Avenue. A proposal to rename Navy Pier after Wilson went nowhere.

In 1927 the council changed Robey Street to Damen Avenue, despite resident protests. When Crawford Avenue was renamed Pulaski Road in 1933, that set off a battle that lasted 19 years before Pulaski was legally accepted. More recently, a proposal to change part of Evergreen Avenue to Algren Street was abandoned in the face of local resistance.

In the 1930s, the Chicago City College system came to the rescue with Woodrow Wilson Junior College. Even that didn't last: In 1969, the school was renamed Kennedy-King College after Robert F. Kennedy and Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. Wilson Avenue on the North and Northwest sides is named after a different Wilson.

The lesson seems to be that changing a street name will always rub some people the wrong way and is a high cost for changes to maps and for businesses. That’s why the city came up with the idea of honorary streets in 1964.

Chicago designated its first honorary street name in 1964, declaring the section of LaSalle Street between Wacker Drive and Jackson Boulevard the "Golden Mile" to honor the city's financial clout. Over the next nearly two decades, only two more signs were designated, according to the Chicago Department of Transportation.

Compiled by Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Living History of Illinois and Chicago®

Chicago,

Government

Looking West from the Top of the Willis (Sears) Tower, Chicago, Illinois.

Living History of Illinois and Chicago®

Animated Image(s),

Chicago

Friday, March 10, 2017

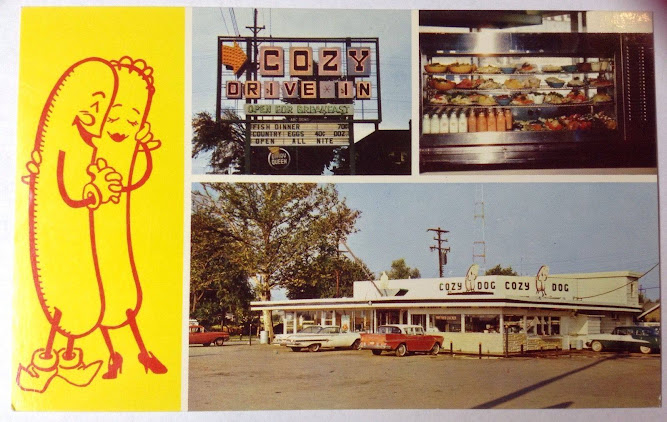

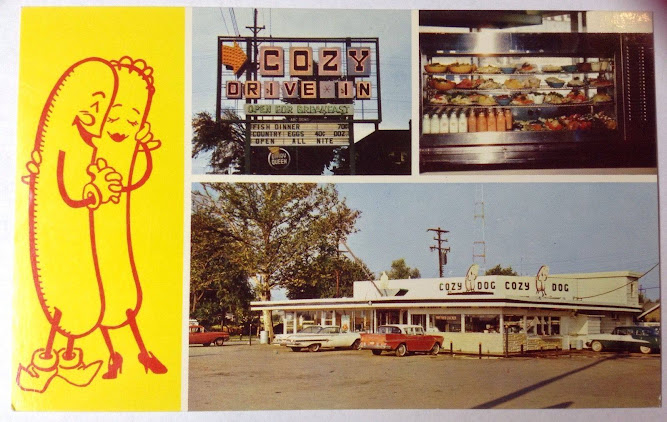

The History of Cozy Dog Drive-In on old Route 66, Springfield, Illinois.

sidebar

It's doubtful that Buzz Waldmire invented the corndog but renamed it the Cozy Dog as a marketing ploy.

- 1941: Pronto Pup in Oregon claims to have invented the corn dog on a stick.

- 1942: Neil and Carl Fletcher start selling "Corny Dogs" at the Texas State Fair.

- 1946: Cozy Dog in Illinois claims to be the first to serve corn dogs on sticks.

The Cozy Dog was invented by Buzz Waldmire. "You'd just better not call it a corndog" because employees are trained to loudly correct you, even if you say corndog a few times.

|

| A Cozy Dog is usually eaten with mustard. The hand-cut french fries are fantastic. |

The first Cozy Dog House was located on South Grand between Fifth and Sixth Street in Springfield, Illinois.

A second Cozy Dog House was located at Ash & MacArthur. The Cozy Dog Drive-In was born; built on the old Route 66, South Sixth Street today, in Springfield, in 1949.

In 1996, Cozy Dog moved to its current location, where Sue (Ed's daughter-in-law), Josh, Eddie, Tony & Nick (Ed's grandsons) continue on with the business right next door to the original location.

In 1996, Cozy Dog moved to its current location, where Sue (Ed's daughter-in-law), Josh, Eddie, Tony & Nick (Ed's grandsons) continue on with the business right next door to the original location.

There is artwork by one of the sons of the late Buzz Waldmire, Bob Waldmire. The famous "Wall Dog" artist, Bob Waldmire, has painted images on the sides of buildings along Route 66. As an artist, he also did postcards, posters, and maps with many pictures of Route 66.

There is artwork by one of the sons of the late Buzz Waldmire, Bob Waldmire. The famous "Wall Dog" artist, Bob Waldmire, has painted images on the sides of buildings along Route 66. As an artist, he also did postcards, posters, and maps with many pictures of Route 66.

Sadly, Bob Waldmire passed away from abdominal cancer on December 16, 2009. There is also some Buzz Waldmire memorabilia inside Cozy Dog, such as family photos and his book collection. Cozy Dog features a gift shop selling Route 66 merchandise.

|

| A 1950s photograph of the first Cozy Dog with a Manager and Ed Waldmire standing in the parking lot. |

|

| Cozy Dog Drive-In, 2935 South Sixth Street, Springfield, Illinois. Route 66. Pen and Ink drawing by William Crook, Jr. ©2010 |

|

| Cozy Dog uses Oscar Mayer Weiners to make their Cozy Dogs. I witnessed an employee open a retail package of Oscar Meyer hot dogs and place them in the steamer. I was personally disappointed. |

|

| An example of Bob Waldmire's artwork. |

|

| Another example of Bob Waldmire's artwork. |

VIDEO

"To the end of Route 66"

by Bob Waldmire

by Bob Waldmire

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Living History of Illinois and Chicago®

Films - Movies - Videos,

Food & Restaurants,

IL West Central,

Illinois Business,

Postcard(s)

The History of Chicago's Famous Bell Maker, Heinrich "Henry" Wilhelm (H.W.) Rincker.

Beginning in Germany.

H.W. (Heinrich Wilhelm) Rincker was born in Herborn, Germany, on June 25, 1818. He was the oldest son of Philipp (1795-1868) and Elizabeth Treupel Rincker (1791-1862), who were wed in 1817. As a young man, H.W. Graduated from the University of Carlsruhe in Germany and married Johannette W. Kunz. H.W.'s father owned & operated the Rincker Bell Foundry (still in existence and now the oldest such foundry in Germany). Mathilde "Tillie" Hemman wrote (H.W.'s granddaughter), "The oldest son traditionally got the business, but H.W. wanted to be a minister. So Philipp disowned his son."

Crossing the ocean to America with 75¢ in his pocket.

Having lost the support of his family, H.W. moved with his wife and children to the United States around 1846. Tillie wrote: "H.W. landed in Chicago penniless. When he and his family arrived in America, he only had 75¢ to his name."

Tillie described how H.W. met an elderly gentleman with a small bell foundry in Chicago. Since H.W. was young and had worked at his father's foundry, the old man was happy to hire him as help. Eventually, the old man sold his bell foundry to H.W., who paid him back a little at a time. H.W. cast many bells for the railroads.

H.W. Rincker owned the first bell foundry on Canal Street near Adams Street, Chicago. Rincker cast the bell for St. Peter's Church, Chicago's largest.

H.W. (Heinrich Wilhelm) Rincker was born in Herborn, Germany, on June 25, 1818. He was the oldest son of Philipp (1795-1868) and Elizabeth Treupel Rincker (1791-1862), who were wed in 1817. As a young man, H.W. Graduated from the University of Carlsruhe in Germany and married Johannette W. Kunz. H.W.'s father owned & operated the Rincker Bell Foundry (still in existence and now the oldest such foundry in Germany). Mathilde "Tillie" Hemman wrote (H.W.'s granddaughter), "The oldest son traditionally got the business, but H.W. wanted to be a minister. So Philipp disowned his son."

Crossing the ocean to America with 75¢ in his pocket.

Having lost the support of his family, H.W. moved with his wife and children to the United States around 1846. Tillie wrote: "H.W. landed in Chicago penniless. When he and his family arrived in America, he only had 75¢ to his name."

Tillie described how H.W. met an elderly gentleman with a small bell foundry in Chicago. Since H.W. was young and had worked at his father's foundry, the old man was happy to hire him as help. Eventually, the old man sold his bell foundry to H.W., who paid him back a little at a time. H.W. cast many bells for the railroads.

H.W. Rincker owned the first bell foundry on Canal Street near Adams Street, Chicago. Rincker cast the bell for St. Peter's Church, Chicago's largest.

1848, H.W. cast the bell for St. Peter's, Chicago's largest church. In 1854, he cast the bell for the Court House, which was used as a public alarm. The Court House bell was destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

Tillie noted that one part of the bell was saved with H.W.'s name on it. When she visited the Chicago Historical Society on "Lincoln Day," she saw it. It's probably still at the Chicago History Museum, though it could be in storage.

Tragedy strikes – twice.

In 1849, Chicago was plagued with its first major cholera epidemic. Sadly, H.W.'s wife, Johannette, and one of their two young sons, Frederick, died. They were buried in Lincoln Park, as were many other victims of the epidemic.

H.W. married a second time in 1851. His new wife, Anna Margareta Ganz (1821-1896), immigrated from Bavaria, Germany.

Of the four children Johannette bore, the last was Mathilde, born in 1848. Tragedy struck again when Mathilde died in 1856 at the age of eight. H.W. was heartbroken. Then he decided to give up his business (through which he'd acquired quite a bit of wealth) and become an Evangelical Lutheran minister as he'd always wished. He and his family moved to Fort Wayne, Indiana, where H.W. continued his religious studies, which had begun in Germany. He was ordained in 1858 and served as minister of Emmanuel Lutheran Church in Fort Wayne for six years.

Life goes on - H.W. as a landowner and minister.

H.W. and second wife Anna went on to have six children, the youngest being Odilie Christina Rincker (1856-1940).

In 1864, H.W. was called to do missionary work in Prairie Township, Shelby County, Illinois, so he and his family returned to Illinois. He bought 600 acres of land in Section 23, which was entirely unbroken. He named it Herborn after his place of birth. Tillie described it as a tough pioneer living: "Prairie weeds so high you could not see a man on horseback, the nearest transportation, mail, and food supplies was 12 miles away in Sigel." She wrote that there were no roads there back then, and in the springtime, when the Wabash River overflowed, the creek they needed to cross to get to Sigel became dangerously swollen. A friend and his son tried to cross the creek one such time. When their wagon was overcome with water, the father managed to grab his son by the hair. They both survived. But the horses drowned, and the wagon was gone.

As a circuit preacher, H.W. eventually organized and led several parishes in Shelby County, Illinois. As Robert Hemman, a great-grandson of H.W., wrote of H.W. in a high school family history project: "He spread the gospel with Bible and rifle." Tillie noted: "H.W. did all his traveling by horseback. One night, when he was coming home, his horse stopped and would not move, so he got off the horse, lit a match and found he was in front of a deep embankment."

In 1865, he was called to become the first pastor of a newly formed Lutheran church in the small town of Sigel in Shelby County. Rev. H.W. Rincker organized the St. Paul's Evangelical Lutheran congregation in Strasburg, Illinois, on April 15, 1866.

Continuing to use his skills as a bellmaker, H.W. established a bell foundry in Sigel, Illinois. In 1866-67, he was called to St.Louis, Missouri, to make (or re-make) bells for some Lutheran churches in that area. At least nine are known to have been made then.

H.W. made a bell for the Sigel church in 1875, although he was no longer the pastor there by then.

H.W. accumulated wealth over the years he was in business and bought a large tract of land in Niles, Illinois.

Daughter Odilie is obedient.

When his youngest daughter, Odilie, was 18, H.W. asked her to marry his good friend, Johann Hemmann (1828-1891), who was 28 years her senior. Johann was recently widowed and the father of four children aged 15 to 21. Although Odilie wanted to be a nurse, she married Johann to please her father. They had two children: Mathilda "Tillie" (1877-1971) and John Emil Hemmann (1890-1954). Johann died when Emil was an infant.

H.W.'s last years.

After living in a small four-room house for many years, H.W. built a large nine-room home and later added a large kitchen and a belfry where he hung his farm bell in Niles Township, Illinois.

Tillie wrote: "Grandfather had the most beautiful large premises. With the choicest pines, trees, and fruit trees. It was just like a park."

H.W. Rincker had a stroke and died in Herborn in 1889. He was 71. In 1896, H.W.'s wife, Anna, died in Herborn at age 75.

Tillie never tired of talking and writing about her Grandfather H.W. I believe she held him in very high esteem.

None of his eight children followed in the bell founding trade.

The passing of H.W. Rincker.

Mr. Rincker, an old and respected citizen of the prairie, was stricken with paralysis Sunday morning and died in his home Wednesday night at 8 o'clock p.m. on November 27, 1889, at the age of 71 years. He was unconscious from the moment of the attack until he died. He was buried in the Rincker cemetery on Saturday, November 30. Mr. Rincker was more than an ordinary man; he was well-educated in the German language and, at the time of his death, had a fine, extensive library. The family and sorrowing friends have the sympathy of all with whom they are acquainted.

Just a year after it was designated a Chicago landmark, the city's second-oldest house, the 129-year-old Heinrich Wilhelm (H.W.) Rincker House at 6384 North Milwaukee Avenue, Chicago, was "accidentally" demolished by the Cirro Wrecking Company on August 25, 1980.

Biography of Heinrich Wilheim (H.W.) Rincker (1818-1889) complied by Patti Hemman Koelle (the Great Great Granddaughter of H.W. Rincker)

Edited by: Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Sources:

|

| The Chicago Courthouse had a Henry W. Rincker bell. The building was destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire. |

|

| The Chicago Courthouse (the center structure) after the Great Chicago Fire in 1871. |

Tragedy strikes – twice.

In 1849, Chicago was plagued with its first major cholera epidemic. Sadly, H.W.'s wife, Johannette, and one of their two young sons, Frederick, died. They were buried in Lincoln Park, as were many other victims of the epidemic.

H.W. married a second time in 1851. His new wife, Anna Margareta Ganz (1821-1896), immigrated from Bavaria, Germany.

|

| H.W. built his new home at 6384 N. Milwaukee Avenue near Devon and Nagel Avenues in 1851, now the site of Walgreens. |

Life goes on - H.W. as a landowner and minister.

H.W. and second wife Anna went on to have six children, the youngest being Odilie Christina Rincker (1856-1940).

|

| Rev. Heinrich Wilhelm Rincker in his robes (date unknown). |

As a circuit preacher, H.W. eventually organized and led several parishes in Shelby County, Illinois. As Robert Hemman, a great-grandson of H.W., wrote of H.W. in a high school family history project: "He spread the gospel with Bible and rifle." Tillie noted: "H.W. did all his traveling by horseback. One night, when he was coming home, his horse stopped and would not move, so he got off the horse, lit a match and found he was in front of a deep embankment."

In 1865, he was called to become the first pastor of a newly formed Lutheran church in the small town of Sigel in Shelby County. Rev. H.W. Rincker organized the St. Paul's Evangelical Lutheran congregation in Strasburg, Illinois, on April 15, 1866.

Continuing to use his skills as a bellmaker, H.W. established a bell foundry in Sigel, Illinois. In 1866-67, he was called to St.Louis, Missouri, to make (or re-make) bells for some Lutheran churches in that area. At least nine are known to have been made then.

H.W. made a bell for the Sigel church in 1875, although he was no longer the pastor there by then.

H.W. accumulated wealth over the years he was in business and bought a large tract of land in Niles, Illinois.

|

| Grain Farm & Residence of W.H. RINCKER - Sec 23, Prairie Tp.(10) P.5, Shelby County, Illinois (1881) |

When his youngest daughter, Odilie, was 18, H.W. asked her to marry his good friend, Johann Hemmann (1828-1891), who was 28 years her senior. Johann was recently widowed and the father of four children aged 15 to 21. Although Odilie wanted to be a nurse, she married Johann to please her father. They had two children: Mathilda "Tillie" (1877-1971) and John Emil Hemmann (1890-1954). Johann died when Emil was an infant.

H.W.'s last years.

After living in a small four-room house for many years, H.W. built a large nine-room home and later added a large kitchen and a belfry where he hung his farm bell in Niles Township, Illinois.

|

| The Henry Rincker House, Niles Township, Illinois |

H.W. Rincker had a stroke and died in Herborn in 1889. He was 71. In 1896, H.W.'s wife, Anna, died in Herborn at age 75.

Tillie never tired of talking and writing about her Grandfather H.W. I believe she held him in very high esteem.

None of his eight children followed in the bell founding trade.

The passing of H.W. Rincker.

Mr. Rincker, an old and respected citizen of the prairie, was stricken with paralysis Sunday morning and died in his home Wednesday night at 8 o'clock p.m. on November 27, 1889, at the age of 71 years. He was unconscious from the moment of the attack until he died. He was buried in the Rincker cemetery on Saturday, November 30. Mr. Rincker was more than an ordinary man; he was well-educated in the German language and, at the time of his death, had a fine, extensive library. The family and sorrowing friends have the sympathy of all with whom they are acquainted.

|

| Before being destroyed by a fire and razed in 1980, the house was the second-oldest in the city and the only remaining example of German Gothic Revival architecture in Chicago. |

Biography of Heinrich Wilheim (H.W.) Rincker (1818-1889) complied by Patti Hemman Koelle (the Great Great Granddaughter of H.W. Rincker)

Edited by: Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Sources:

- Anna Wilhelmine Mathilde "Tillie" Hemmann (1877-1971) through her recollections and writings during the 1950s and the 1960s.

- Rincker Family History (1795-1962).

- "The History of Chicago" by Hon: John Moses and Joseph Kirkland, Volume 2, Published by Munsell & Co. 1895, Page 407, Ch. 9 - Part 4.

- Autobiography of Robert J. E. Hemman (mid 1930s), Great Grandson of H.W. Rincker.

- Rosadelle Hemman Schultz (Robert Hemman's sister) in a taped interview in the 1980s.

- Robert J. E. Hemman's genealogy research.

- Biographical Record of Shelby County.

- Family history research by Patricia Hemman Koelle.

Living History of Illinois and Chicago®

Chicago,

Famous,

Illinois Business

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)