The World's Columbian Exposition tried to show the world — and the rest of America — the best Chicago had to offer. But many Chicagoans lived a much darker existence outside the fair's gates.

Much of Chicago's industry centered on the Union Stock Yards and meat-processing plants. The smoke, stench, and filth surrounding the packing operations drove many well-off residences to other Chicago communities and some to the cleaner suburbs. Those who labored in the yards continued to live nearby in what was known as Packingtown.

Thousands of immigrants lived in crowded tenement buildings and worked long hours, six days a week; the average wage for a meat packer was less than 20¢ an hour ($7.60/hr today), and many laborers made far less.

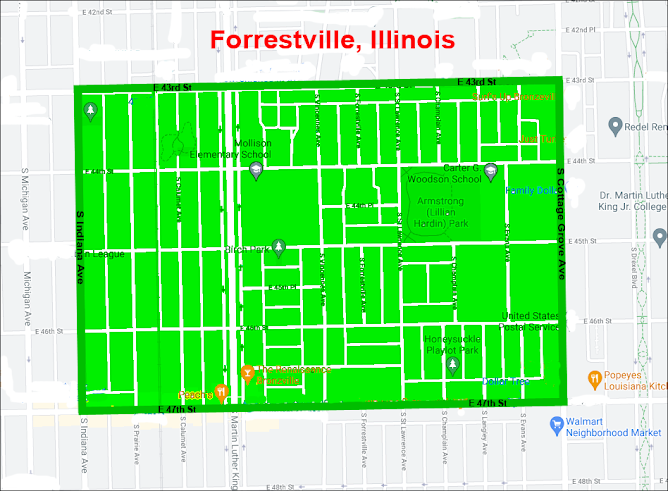

|

| Packingtown is just outside of the Union Stock Yards. |

Many Chicago neighborhoods not directly affected by the stockyards were also dirty, smelly, and unsafe. Garbage was dumped in the streets, and corpses of animals were left to rot. The water supply was notoriously unhealthy; hundreds of people, particularly children, died of cholera and other preventable diseases every year.

Bubbly Creek was originally a wetland; during the 19th century, channels were dredged to increase the flow rate into the Chicago River and dry out the area to increase the amount of habitable land in the fast-growing city. The South Fork of the South Branch of the Chicago River became an open sewer for the local stockyards, especially the Union Stock Yards and the packing houses. Meatpackers dumped waste, such as blood and entrails, into the river. The creek received so much blood and offal (decomposing animal flesh) that it began to bubble methane and hydrogen sulfide gas from decomposition products.

|

| Bubbly Creek in 1915. |

In 1906, author Upton Sinclair wrote "The Jungle," an unflattering portrait of America's meatpacking industry. In it, he reported on the state of Bubbly Creek, writing that:

"Bubbly Creek is an arm of the Chicago River, and forms the southern boundary of the Union Stock Yards; ALL the drainage of the square mile of packing houses empties into it so that it is really a great open sewer a hundred or two feet wide. One long arm of it is blind, and the filth stays there forever and a day. The grease and chemicals that are poured into it undergo all sorts of strange transformations, which are the cause of its name; it is constantly in motion as if huge fish were feeding in it, or great leviathans disporting themselves in its depths. Bubbles of carbonic gas will rise to the surface and burst, and make rings two or three feet wide. Here and there the grease and filth have caked solid, and the creek looks like a bed of lava; chickens walk about on it, feeding, and many times an unwary stranger has started to stroll across and vanished temporarily. The packers used to leave the creek that way, till every now and then the surface would catch on fire and burn furiously, and the fire department would have to come and put it out. Once, however, an ingenious stranger came and started to gather this filth in scows (a large flat-bottomed boat for transporting bulk material and dredging), to make lard out of; then the packers took the cue, and got out an injunction to stop him, and afterward gathered it themselves. The banks of Bubbly Creek are plastered thick with hairs, and this also the packers gather and clean."

|

| Bubbly Creek Today. |

The World's Fair organizers were so afraid of a cholera outbreak among fair visitors that they built a pipeline to bring clean water from Waukesha, Wisconsin, about 115 miles to the north. The city was characterized by overcrowded schools, filth, rampant crime, and hundreds of brothels in several red-light districts.

English politician John Burns, who visited Chicago in 1895, called Chicago a "pocket edition of hell." Later, he added, "On second thought, I think hell is a pocket edition of Chicago."

How dirty was Chicago? In the late 1890s, Chicago had about 83,000 horses living and working in the city. On average, one horse creates between 40 and 50 pounds of manure daily at 40 pounds, which equals 3,320,000 pounds, or 1,660 tons of horse manure to dispose of daily. "Manure Mongers" (street sweepers) would sweep up the horse manure. By 1900, there were only 377 automobiles registered with the Board of Examiners of Operators of Automobiles. What happens to all that manure?  |

| 1890s Chicago Traffic |

Many of the poor probably didn't see the White City except from a distance. Although the fair's organizers were pressed to provide a "Waif's Day." (Waif: a homeless, neglected, or abandoned child)." But Harlow Niles Higinbotham, World's Fair President, said peremptorily (subject to no further debate or dispute), "NO!"

The United States as a whole was struggling during the year of the fair. The Panic of 1893 was a severe depression that bankrupted railroads and triggered runs on banks. Even the wealthy struggled, and many middle-class families who might have traveled to the fair stayed home. The poor were even less likely to experience the wonders of the exposition.

Fair revenues from gate admission, concessions, and exhibitors reached $35 million ($1.1 billion today). After all the expenses were paid, the net profit was about $2 million ($61 million today), split amongst shareholders.

SIDEBAR

The Observation 'Ferris' Wheel, opened 52 days late on June 21, 1893, earning $733,086 ($22,237,000 today) at 50¢ ($15 today; same as the cost to enter the fair) per a 2-rotation ride (one rotation to load/unload passengers, six cars at a time, and one complete rotation). Receipts were second to the "Street in Cairo" exhibit at $787,826 ($23,898,000 today).

Amazing one-minute film footage of the Ferris Wheel

Wrightwood in Chicago's Lincoln Park.

The vantage point looks from the southwest

corner of Wrightwood towards the northeast across Clark Street.

Filmed by the Lumiere Brothers © 1893.

This is one of the first films ever shot in Chicago.

ADDITIONAL READING: Racism at Chicago's 1893 World's Columbian Exposition.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.