Walgreens began in 1901, with a small food front store on the corner of Bowen and Cottage Grove Avenues in Chicago, owned by Dixon, Illinois native Charles R. Walgreen. By 1913, Walgreens had grown to four stores on Chicago's South Side. It opened its fifth in 1915 and four more in 1916.

It would be impossible to tell the story of Walgreens drugstores without telling the story of Charles R. Walgreen, Sr., who started it all. Walgreen was born near Galesburg, Illinois, before his family relocated to Dixon, Illinois — a town 60 miles north of his birthplace — when his father, a farmer turned businessman, saw the tremendous commercial potential of the Rock River Valley. It was here that Walgreen, at the age of 16, had his first experience working in a drugstore, though it was far from a positive one.

It would be impossible to tell the story of Walgreens drugstores without telling the story of Charles R. Walgreen, Sr., who started it all. Walgreen was born near Galesburg, Illinois, before his family relocated to Dixon, Illinois — a town 60 miles north of his birthplace — when his father, a farmer turned businessman, saw the tremendous commercial potential of the Rock River Valley. It was here that Walgreen, at the age of 16, had his first experience working in a drugstore, though it was far from a positive one.

Working at Horton's Drugstore (for $4 a week) was a job he took only because of an accident that left him unable to participate in sports. While working in a local shoe factory, Walgreen accidentally cut off the top joint of his middle finger, ending his athletic competition. If not for the accident, Walgreen might never have become a pharmacist, business owner, and phenomenally successful entrepreneur. Ironically, his initial experience working at Horton's was a failure, and Walgreen left after just a year and a half on the job.

Still, Walgreen realized that his future lay not in Dixon but in Chicago, a far larger city. Yet in 1893, the year of Walgreen's arrival, Chicago was far from promising for a future drugstore entrepreneur. More than 1,500 drugstores already competed for business (many exceedingly successful), and customers needed more choice. Given this stiff competition, Walgreen's ultimate achievements are remarkable.

Determined not to rely on his family's resources to sustain himself, Walgreen resolved to succeed independently. In fact, faced with the prospect of being completely broke shortly after he arrived in Chicago, Walgreen defiantly tossed his few remaining pennies into the Chicago River, forcing himself to commit to his profession and a lifetime of perseverance and hard work. A lesson well learned — and never forgotten by Walgreen.

In a series of jobs with Chicago's leading pharmacists — Samuel Rosenfeld, Max Grieben, William G. Valentine, and, most importantly, Isaac W. Blood, Walgreen grew increasingly knowledgeable and dissatisfied with what he saw as old-fashioned, complacent methods of running a drugstore. Where was the desire to provide superb customer service? Where were the innovations in merchandising and store displays? Where was the selection of goods that customers really wanted and could afford? Where was the sense of trying to understand, please, and serve the many needs of drugstore customers? And, most of all, where was the commitment to providing genuine value to the customer? The answer was obvious: Walgreens had to open a new pharmacy.

Working at Horton's Drugstore (for $4 a week) was a job he took only because of an accident that left him unable to participate in sports. While working in a local shoe factory, Walgreen accidentally cut off the top joint of his middle finger, ending his athletic competition. If not for the accident, Walgreen might never have become a pharmacist, business owner, and phenomenally successful entrepreneur. Ironically, his initial experience working at Horton's was a failure, and Walgreen left after just a year and a half on the job.

Still, Walgreen realized that his future lay not in Dixon but in Chicago, a far larger city. Yet in 1893, the year of Walgreen's arrival, Chicago was far from promising for a future drugstore entrepreneur. More than 1,500 drugstores already competed for business (many exceedingly successful), and customers needed more choice. Given this stiff competition, Walgreen's ultimate achievements are remarkable.

Determined not to rely on his family's resources to sustain himself, Walgreen resolved to succeed independently. In fact, faced with the prospect of being completely broke shortly after he arrived in Chicago, Walgreen defiantly tossed his few remaining pennies into the Chicago River, forcing himself to commit to his profession and a lifetime of perseverance and hard work. A lesson well learned — and never forgotten by Walgreen.

In a series of jobs with Chicago's leading pharmacists — Samuel Rosenfeld, Max Grieben, William G. Valentine, and, most importantly, Isaac W. Blood, Walgreen grew increasingly knowledgeable and dissatisfied with what he saw as old-fashioned, complacent methods of running a drugstore. Where was the desire to provide superb customer service? Where were the innovations in merchandising and store displays? Where was the selection of goods that customers really wanted and could afford? Where was the sense of trying to understand, please, and serve the many needs of drugstore customers? And, most of all, where was the commitment to providing genuine value to the customer? The answer was obvious: Walgreens had to open a new pharmacy.

|

| Charles Walgreen's first store in Barrett's Hotel at Cottage Grove and Bowen Avenue on Chicago's South Side. |

|

| Interior of the first Walgreens store. |

However, it was not until 1901 that Walgreen put together enough money for the down payment on his pharmacy. He wanted to buy the store where he was working, owned by Isaac Blood. Walgreen had been not only a trusted employee but a valuable business advisor as well. Yet even given Walgreen's outstanding business counsel on Blood's behalf, Blood was unyielding in selling to Walgreen, raising his asking price from $4,000 to $6,000. Though it would take years for Walgreen to pay off the loan he signed for the purchase, he went ahead. He was now his own man and well on his way to building one of the most remarkable businesses in America.

Walgreen's drugstore was located in Barrett's Hotel at Cottage Grove and Bowen Avenue on Chicago's South Side. Initially built in anticipation of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition, this was a thriving neighborhood. The store, however, was struggling. Dim and poorly merchandised, Walgreen's first real challenge was his ideas on store layout, selection, service, and pricing.

Walgreen's drugstore was located in Barrett's Hotel at Cottage Grove and Bowen Avenue on Chicago's South Side. Initially built in anticipation of the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition, this was a thriving neighborhood. The store, however, was struggling. Dim and poorly merchandised, Walgreen's first real challenge was his ideas on store layout, selection, service, and pricing.

By every account, Walgreen succeeded brilliantly by practicing what he preached and instituting what he felt were clearly needed innovations. New, bright lights were installed to create a cheerful, warm ambiance in the store. Walgreen or his colleague, Arthur C. Thorsen, personally greeted each customer. Aisles were widened, creating a spacious, airy, welcoming feeling - a far cry from the cramped interiors of other drugstores. The selection of merchandise was improved and broadened, including pots and pans (unheard of in a drugstore!) at the bargain price of 15¢ a piece! Prices were kept fair and reasonable. The quality of Walgreen's pharmaceutical compounds (he became a registered pharmacist in 1897) met the highest standards for purity and freshness. Efficiency was increased. But Walgreens most dramatic change was a level of service and personal attention unequaled by virtually any other pharmacy in Chicago. And this was exemplified by Walgreen's famous...

Whenever a customer in the immediate area telephoned with an order for non-prescription items, Walgreens constantly repeated — loudly and slowly — the caller's name, address and items ordered. That way, assistant and handyman Caleb Danner could quickly prepare the order. Then Walgreen would prolong the conversation by discussing everything from the weather to current events. Invariably, Caleb would be at the caller's door before she was ready to hang up. She would then excuse herself and return to the phone, amazed at how fast her order had been delivered.

While Walgreens couldn't do this for customers living farther away, those who did benefit from it were thrilled and delighted to tell their friends about Charles Walgreen and his incredible service.

The second Walgreen store opened in 1909 on Chicago's South Side and would remain for many years Walgreen's base of operations and the locale for the first wave of stores he was to eventually open. By transforming one quiet, average drugstore, Charles Walgreen had shaken up the entire drugstore business.

By every account, Walgreen succeeded brilliantly by practicing what he preached and instituting what he felt were clearly needed innovations. New, bright lights were installed to create a cheerful, warm ambiance in the store. Walgreen or his colleague, Arthur C. Thorsen, personally greeted each customer. Aisles were widened, creating a spacious, airy, welcoming feeling - a far cry from the cramped interiors of other drugstores. The selection of merchandise was improved and broadened, including pots and pans (unheard of in a drugstore!) at the bargain price of 15¢ a piece! Prices were kept fair and reasonable. The quality of Walgreen's pharmaceutical compounds (he became a registered pharmacist in 1897) met the highest standards for purity and freshness. Efficiency was increased. But Walgreens most dramatic change was a level of service and personal attention unequaled by virtually any other pharmacy in Chicago. And this was exemplified by Walgreen's famous...

Whenever a customer in the immediate area telephoned with an order for non-prescription items, Walgreens constantly repeated — loudly and slowly — the caller's name, address and items ordered. That way, assistant and handyman Caleb Danner could quickly prepare the order. Then Walgreen would prolong the conversation by discussing everything from the weather to current events. Invariably, Caleb would be at the caller's door before she was ready to hang up. She would then excuse herself and return to the phone, amazed at how fast her order had been delivered.

While Walgreens couldn't do this for customers living farther away, those who did benefit from it were thrilled and delighted to tell their friends about Charles Walgreen and his incredible service.

The second Walgreen store opened in 1909 on Chicago's South Side and would remain for many years Walgreen's base of operations and the locale for the first wave of stores he was to eventually open. By transforming one quiet, average drugstore, Charles Walgreen had shaken up the entire drugstore business.

|

| Street Level Soda Fountain — Walgreen Co. State and Randolph Streets, Chicago, Illinois. |

|

| The Oak Room Cafeteria was a basement-level cafeteria at the Walgreen Co. State and Randolph Streets, Chicago. There was a lower-level entrance from the CTA Howard-Englewood (North-South) subway. |

And Walgreen's next innovations took place in the soda fountain — where milkshakes had long been a staple of American drugstores.

The year was 1910. Walgreens now had two stores. His challenge is finding ever-new ways of satisfying a growing customer base while outshining his competitors.

Over the preceding 100 years, the soda fountain had become vital to virtually every American drugstore. In the early 19th century, bottled soda and later charged soda water were considered necessary health aids, making it a natural fixture in drugstores. A tin pipe and spigot were attached to dispense the icy-cold charged water. Soon, flavored syrups were added to the fizzy water, then ice cream was added later. As sodas grew in popularity, the "soda fountain" grew in beauty, ornamentation, and importance as a revenue source for the drugstore. Manufacturers vied in creating ornate fountains, with onyx countertops and fixtures of silver and bronze and lighting by Tiffany.

Walgreens was no exception to such a popular trend. Indeed, its soda fountains were among Chicago's most beautiful. Yet, the items the soda fountains served — ice cream and fountain creations — were invariably cold. And cold items are only sold in hot weather. That meant drugstore owners everywhere were resigned to mothballing their soda fountains each fall until the warm weather returned. Thus, the drugstores lost a critical revenue stream, not to mention the valuable store space that could have been used for other profitable purposes.

However, accepting the status quo was not one of Charles Walgreen's strong points. His response to this dilemma was typically double-barreled: an idea that benefited his customers as much as his company. "Why not serve hot food during cold weather?" Beginning with simple sandwiches, soups, and desserts, Walgreen kept his fountain open during the winter and provided his customers with affordable, nutritious, home-cooked meals. And the food was home-cooked, thanks to Charle's wife, Myrtle Walgreen. All menu items — from her chicken, tongue, and egg salad sandwiches to bean or cream of tomato soup to the cakes and pies — were prepared by Myrtle Walgreen in their home kitchen. She rose at dawn and finished cooking by 11 AM, and the food was then delivered fresh to Walgreen's two stores.

As a result of this common-sense innovation, Walgreen again demonstrated his knack for helping his company better serve the public. From then on, through the 1980s, food service was an integral part of Walgreen's story. Every Walgreens was outfitted with comfortable, versatile soda fountain facilities serving breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Just as Walgreens had reasoned, customers who eat at Walgreens usually stayed to purchase other necessary items. And loyalty to Walgreens increased exponentially with its friendly waitresses, wholesome food, and fair prices.

By 1913, Walgreens had grown to four stores, all on Chicago's South Side. The fifth Walgreens opened in 1915, and the ninth opened in 1916. By 1919, there were 20 stores in the rapidly growing chain.

As impressive as this growth was, even more remarkable was the superb management team that Walgreen had begun to assemble since his second store opened. Walgreen would often say — without any show of false modesty — that one of his most incredible talents was his ability to recognize, hire and promote people he considered smarter than he was. Among these early managers and executives were people who would guide Walgreens into national prominence for decades to come: William Scallion, A.L. Starshak, Willis Kuecks, Arthur C. Thorsen, James Tyson, Arthur Lundecker, John F. Grady, Roland G. Schmitt, Harry Goldstine, and later, the invaluable Robert Greenwell Knight, whom Walgreen hired from McKinsey and Company after Knight completed a visionary strategic study of Walgreen's entire operation and future.

In his ability to spot talent, Walgreen was rarely wrong. In fact, his uncanny ability to hire extended even as far as the people who manned his soda fountain, including the man who created Walgreen's next sensation.

By 1920, 20 stores strong and proliferating, Walgreens was a regular fixture on Chicago's retail scene. Throughout this decade, Walgreens underwent phenomenal growth.

The year was 1910. Walgreens now had two stores. His challenge is finding ever-new ways of satisfying a growing customer base while outshining his competitors.

|

| Walgreen Co. State and Randolph Streets, Chicago, Illinois. |

|

| Walgreen Co. State and Madison Streets, Chicago, Illinois. |

However, accepting the status quo was not one of Charles Walgreen's strong points. His response to this dilemma was typically double-barreled: an idea that benefited his customers as much as his company. "Why not serve hot food during cold weather?" Beginning with simple sandwiches, soups, and desserts, Walgreen kept his fountain open during the winter and provided his customers with affordable, nutritious, home-cooked meals. And the food was home-cooked, thanks to Charle's wife, Myrtle Walgreen. All menu items — from her chicken, tongue, and egg salad sandwiches to bean or cream of tomato soup to the cakes and pies — were prepared by Myrtle Walgreen in their home kitchen. She rose at dawn and finished cooking by 11 AM, and the food was then delivered fresh to Walgreen's two stores.

As a result of this common-sense innovation, Walgreen again demonstrated his knack for helping his company better serve the public. From then on, through the 1980s, food service was an integral part of Walgreen's story. Every Walgreens was outfitted with comfortable, versatile soda fountain facilities serving breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Just as Walgreens had reasoned, customers who eat at Walgreens usually stayed to purchase other necessary items. And loyalty to Walgreens increased exponentially with its friendly waitresses, wholesome food, and fair prices.

By 1913, Walgreens had grown to four stores, all on Chicago's South Side. The fifth Walgreens opened in 1915, and the ninth opened in 1916. By 1919, there were 20 stores in the rapidly growing chain.

As impressive as this growth was, even more remarkable was the superb management team that Walgreen had begun to assemble since his second store opened. Walgreen would often say — without any show of false modesty — that one of his most incredible talents was his ability to recognize, hire and promote people he considered smarter than he was. Among these early managers and executives were people who would guide Walgreens into national prominence for decades to come: William Scallion, A.L. Starshak, Willis Kuecks, Arthur C. Thorsen, James Tyson, Arthur Lundecker, John F. Grady, Roland G. Schmitt, Harry Goldstine, and later, the invaluable Robert Greenwell Knight, whom Walgreen hired from McKinsey and Company after Knight completed a visionary strategic study of Walgreen's entire operation and future.

In his ability to spot talent, Walgreen was rarely wrong. In fact, his uncanny ability to hire extended even as far as the people who manned his soda fountain, including the man who created Walgreen's next sensation.

|

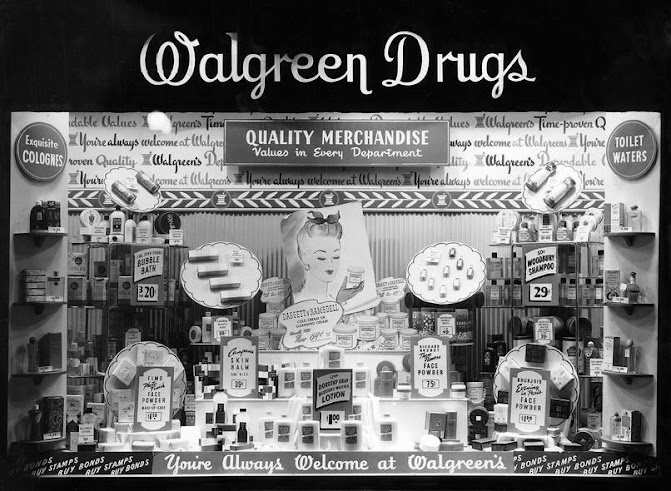

| Walgreen's Window Display. Circa 1920 |

By 1920, 20 stores strong and proliferating, Walgreens was a regular fixture on Chicago's retail scene. Throughout this decade, Walgreens underwent phenomenal growth.

By 1929, Walgreens stores reached 525, including locations in New York City, Florida, and other major markets. Many factors contributed to this unprecedented growth: a superb management team, modern merchandising, innovative store design, fair pricing, outstanding customer service, and exceedingly high pharmacy quality and service.

Yet, one can't overlook something that may have seemed a minor innovation at the time. The invention of Walgreens immortal malted milkshake in 1922, an instant classic, by Ivar "Pop" Coulson, the backbone of the Walgreens soda fountain since 1914. Coulson had always been eager to improve on whatever he and his fountain clerks had to offer, and he made generous use of Walgreens extra-rich ice cream, manufactured in Walgreen's own plant on East 40th Street in Chicago. Until then, malted milk drinks were made by mixing milk, chocolate syrup, and a spoonful of malt powder in a metal Walgreens employees working at soda fountain container, then pouring the mixture into a glass. One sweltering summer day, Coulson set off his revolution. He added a generous scoop of vanilla ice cream to the basic mix, then added another scoop. Coulson's new malted milkshake came with a glassine bag containing two complimentary vanilla cookies from the company bakery.

Walgreens Customers at the Soda Fountain Response could not have been more substantial if Coulson had found a cure for the common cold! His luscious creation was adopted by fountain managers in every Walgreens store. It was written in newspapers and talked about in every city with a Walgreens. But most of all, it was the object of much adoration. It was common to see long lines outside Walgreens stores, and customers stood three or four feet deep at the fountain waiting for the new drink. Suddenly, "Meet me at Walgreens for a shake and a sandwich" became bywords as popular as "Meet me under the Marshall Fields clock" at State and Randolph in Chicago.

Walgreens Customers at the Soda Fountain Response could not have been more substantial if Coulson had found a cure for the common cold! His luscious creation was adopted by fountain managers in every Walgreens store. It was written in newspapers and talked about in every city with a Walgreens. But most of all, it was the object of much adoration. It was common to see long lines outside Walgreens stores, and customers stood three or four feet deep at the fountain waiting for the new drink. Suddenly, "Meet me at Walgreens for a shake and a sandwich" became bywords as popular as "Meet me under the Marshall Fields clock" at State and Randolph in Chicago.

So, once again, Charles Walgreen's prediction that his soda fountain would be essential to his stores as a source of revenue, company growth, and increased customer satisfaction (which translated into even higher levels of customer loyalty and patronage) came true. In its own way, Coulson's malted fueled Walgreen's dramatic growth.

sidebar

During prohibition (1920-1933), drug stores could legally sell alcohol. It was one of many ways that people could get legal alcohol.

Over the years, he worked at various drugstores while studying pharmacy at night. At one point, he had only 5¢ to his name. So he bought a newspaper for 2¢ and threw the other 3 into the Chicago River for good luck. It worked (eventually).

|

| On July 1, 1927, Walgreens opened a new store at the Montgomery Ward Tower Building. |

Surviving and Conquering the Great Depression.

By 1930, Walgreens had over 500 stores and quickly became the nation's most prominent drugstore chain. And while Walgreens was no more immune to the dire effects of a shrinking economy than other American businesses, it persevered. Walgreens continued to develop new, meaningful ways to serve customers and — just as importantly — employ thousands of people during this period of extreme economic distress. As a testament to Walgreens continuing quality and stability, its stock (having become a publicly traded corporation in 1927) continued to increase in price.

Throughout this period, Walgreens continued to innovate. It had already become convinced of the value of advertising and remained one of the biggest newspaper advertisers in Chicago and other parts of the country. In fact, Walgreens ran the most extensive promotion campaign in its history — costing more than $75,000 — during 1931. Perhaps even more significant was Walgreen's entry into broadcast advertising. Also, in 1931, Walgreens became the first drugstore chain in the country to advertise on the radio, with legendary Chicago Cubs announcer Bob Elson as the "voice" of Walgreens.

|

| Walgreen Drugs, SE corner of Devon and Western, Chicago, Illinois. (circa 1931) |

Major philanthropy also became an essential corporate mission during this time. In 1937, Charles Walgreen began his association with the University of Chicago by donating $550,000 in company stock to establish the Charles R. Walgreen Foundation for the Study of American Institutions.

Yet in 1939, just as the company emerged victorious during the great Charles Walgreen challenge, Charles Walgreen died at 66 years old. He was always the planner and visionary, leaving his company in superb condition and prepared for the future. In addition to a robust and disciplined management team, he had groomed his son, Charles Walgreen Jr., to lead Walgreens into the next decade and beyond.

Walgreens is the story of a company that has never rested on its laurels. They found new ways to satisfy their customers and stay ahead of the curve in operating their business.

During World War II, Walgreens established a not-for-profit pharmacy in the Pentagon, a service for which it was formally recognized by President Eisenhower. The Pentagon Walgreens was a significant marketer of War Bonds during the war effort.

Walgreens was among the first American companies to establish profit-sharing and pension plans to assure employee security. The initial funds for the pension — $500,000 in cash — were contributed by the personal estate of Charles R. Walgreen Sr. in a plan called "a landmark in American industrial relations" by The Chicago Daily News.

Following the war, Walgreens was among the first drugstore chains to see the importance of a new wave in retailing — the "self-service" concept — and implement it across all its stores.

|

| Walgreens. Lincoln Avenue and Oakton Street, Skokie, Illinois. |

By this time, a third Walgreen was at the helm: Charles R. "Cork" Walgreen III. He realized continued prosperity could only come through steady progress like his predecessors.

By 1984, Walgreens opened its 1,000th store. As Illinois Governor James Thompson said to mark that occasion, "Walgreens has been a pioneer, not just in pharmaceuticals, but in retail service as well, since 1901. It's not just that Walgreens is an old and famous name in Chicago, Illinois, and nationwide. "Walgreens is still thriving, and I think that's because of their quality and leadership in innovation." People depend upon them because their service and products are consistent, from store to store, year to year, customer to customer.

"In this life of uncertainty, people from my generation like to reach back and cling to the 'good old days.' Sometimes, the good old days never really existed except in our imaginations. Walgreen's good old days always existed, and the very comforting thing is that they're still here!"

|

| Walgreens New Stand-Alone Store Style. |

Walgreens Chronology

In 1922, a Walgreens employee, Ivan "Pop" Coulson, sought to improve the company's chocolate malt beverage. Coulson was always mixing concoctions as a wizard at the soda fountain. The original recipe was milk, chocolate syrup, and a spoonful of malt powder. However, with one added ingredient, Coulson would create a magnificently delicious beverage that would stand the test of time. Using 'generous' scoops of vanilla ice cream manufactured in Walgreen's plant gave the malt beverage a thick consistency and a richer taste. Customers stood three and four deep around the soda fountain to buy the "double-rich chocolate malted milk."

The 100th store opened in Chicago in 1926.

In 1927, Walgreen Co. stock went public.

Walgreens helped celebrate Chicago's Century of Progress World's Fair in 1933/34. The company opened four stores on the Century of Progress fairgrounds. These stores experimented with advanced fixture design, new lighting techniques, and colors - ideas that helped modernize drugstore layout and design.

|

| Chicago's Century of Progress World's Fair in 1933/34. |

Charles Walgreen Sr. died, and Charles Walgreen Jr. became the company's President in 1939.

In 1943, Walgreens opened a nonprofit 6,000-square-foot drugstore in the Pentagon in Washington, D.C. All the profits from the store went to the Pentagon Post Restaurant Council, which supervised food service in the complex. The store operated into the 1980s.

In 1950 Walgreens began to build self-service instead of clerk service stores in the Midwest. By 1953, Walgreens was the largest self-service retailer in the country.

Walgreens filled its 100 millionth prescription in 1960, far more than any drug chain then.

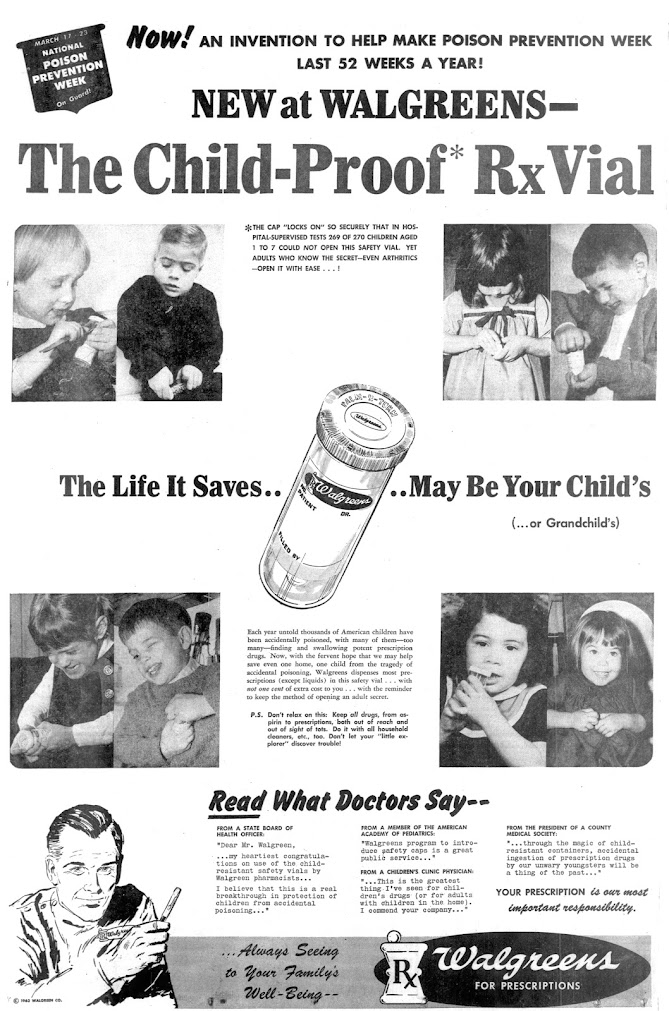

Walgreens became the first major drug chain in 1968 to put its prescriptions into child-resistant containers long before the law required it.

Charles Walgreen III became the company's President in 1969.

Wag's was a chain of casual "family" dining restaurants owned and operated by Walgreens beginning in 1974 and closed in 1991. They were modeled after restaurants like Big Boy and Denny's in that they were mostly 24-hour establishments specializing in inexpensive fare such as hamburgers and breakfast. Wag's baked, on-site, pies, cakes, and pastries. The chain was based on smaller restaurants that existed in some of the larger Walgreens stores.

Walgreens sold all 91 freestanding stores to Marriott Corporation in 1988, retaining only a few locations that were situated in malls. Soon after this, Marriott began selling off its assets. Unable to find a buyer for most of the restaurants, the Wag's chain was completely out of business by 1991. However, the 30 Wag's restaurants in the Chicago Metropolitan area were sold to Lunan Corporation (a large Arby's franchisee in Chicago) and run by Lunan Family Restaurants. Over the course of 2 years, each Wag's restaurant continued to do business as Wag's until converted to a Shoney's restaurant. Lunan Family Restaurants went out of business in 1994, and the Shoney's locations were sold to various chains or individuals. Some locations continue to this day as IHOP restaurants. Marriott itself ceased operations in 1993 when it split into two new entities.

Walgreens reached $1 billion in sales in 1975. Walgreen Co. moved into a new corporate headquarters in Deerfield, a suburb of Chicago.

In 1981, The first Intercom computers were installed in five Walgreens pharmacies in Des Moines, Iowa. This was the initial step toward making Walgreens the first drugstore chain to connect all its pharmacy departments via satellite.

Next-day photofinishing became available chainwide in 1982.

In 1984, Walgreens opened its 1,000th store at 1200 N. Dearborn in Chicago.

In November 1991, the chain installed point-of-sale scanning to speed checkouts. Walgreens opened its first drugstore with a drive-thru pharmacy.

The 2,000th store opened in 1994 in Cleveland, Ohio.

In 1997, Intercom Plus, Walgreen's advanced computer system, completed its rollout to all stores. Intercom Plus speeds the prescription-filling process, permits better patient counseling, and is the leading pharmacy system in the industry.

Walgreens.com launched a comprehensive online pharmacy, offering customers a convenient and secure way to care for many pharmaceutical and healthcare needs online 1999. Charles Walgreen III retired as chairman of the company.

Walgreens reached the 4,000-store mark when Coldwater Canyon Avenue and Magnolia Boulevard in Van Nuys, California, opened in March 2003.

Walgreens opened its 5,000th store in Richmond, Virginia, in October 2005

In July 2006, Walgreens acquired Happy Harry's drugstore chain, adding 76 stores, primarily in Delaware. In the fall, Walgreens began offering in-store health clinics, today called Healthcare Clinics, with nurse practitioners treating walk-in patients for common ailments. During 2006, clinics opened in St. Louis, Kansas City, Chicago, and Atlanta.

In 2007, Walgreens acquired Take Care Health Systems. In the summer of 2007, Walgreens acquired Option Care, a network of over 100 pharmacies (including more than 60 company-owned) in 34 states, providing a full spectrum of specialty pharmacy and home infusion services. In the fall of 2007, Walgreens opened its first store in Honolulu, Hawaii, and celebrated the opening of its 6,000th store in New Orleans.

Walgreens opened its first store in Alaska in 2009, marking its presence in all 50 states. The company celebrated the opening of its 7,000th store nationwide with a grand opening in Brooklyn, N.Y. Walgreens offered H1N1 vaccinations nationwide at all of its pharmacies and clinics to fight the flu pandemic.

Charles R. Walgreen III retired from the company's board of directors after 46 years of service in 2010. Walgreens completed its acquisition of the Duane Reade drugstore chain from New York and opened its first "Well Experience" format stores in Oak Park and Wheeling, Illinois.

In 2012, Walgreens debuted its Chicago flagship store, returning to the iconic shopping corner of State and Randolph in Chicago's Loop, where it operated a store from 1926 to 2005. Walgreens acquired Bioscrip's community specialty pharmacies and centralized specialty and mail-service pharmacy businesses. Walgreens launched a new online "Find Your Pharmacist" tool that allows customers to select a pharmacist by matching their health care needs with the areas of expertise, specialties, languages, and clinical backgrounds of Walgreens pharmacists. Walgreens and Alliance Boots announced they have entered a strategic transaction to create the first global pharmacy-led health and wellbeing enterprise. Also, Walgreens opened its 8,000th store in Los Angeles.

On December 31, 2014, Walgreens took its products and services to the world's four corners after its merger with Alliance Boots, a leading international pharmacy-led health and beauty group. With the completion of the merger came the formation of a new global company, "Walgreens Boots Alliance, Inc." which combined the two leading companies with iconic brands, complementary geographic footprints, shared values, and a heritage of trusted healthcare services through pharmaceutical wholesaling and community pharmacy care. Both Walgreens and Boots date back more than 100 years.

Walgreens Boots Alliance, Inc., was formed on December 31, 2014, after Walgreens purchased a 55% stake in Alliance Boots that it did not already own. It also engages in the pharmaceutical wholesaling and distribution business in Germany. As of August 31, 2021, this segment operated 4,031 retail stores under the Boots, Benavides, and Ahumada in the United Kingdom, Thailand, Norway, the Republic of Ireland, the Netherlands, Mexico, and Chile; and 548 optical practices, including 160 on a franchise basis. Walgreens Boots Alliance, Inc. was founded in 1901, is based in Deerfield, Illinois, United States, and boasts 277,000 employees worldwide.

Walgreens Boots Alliance, Inc. is an American holding company based in Deerfield, Illinois, United States.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.