|

| The New Fire-Proof Hotel LaSalle, Chicago, Illinois. (1910) |

The building is designed in the style of the French Renaissance, with a mansard roof, which gives the great structure a striking appearance. Large windows and balconies relieve what would otherwise be a plain front and provide an artistic and unique effect.

|

| Hotel LaSalle Main Dining Room, October 30, 1909. |

Main Dining Hall—500Palm Room—350Henry II—500German Room—350Cafe—175Banquet Hall (Large)—1,000Banquet Hall (Medium)—600Banquet Hall (Small)—200=======================Total Seating Capacity—3,675

In addition, several smaller private dining halls seat from 50 to 100 each that may be called into use.

Per hotel advertising, the famous Pabst Blue Ribbon beer was served in the buffets and restaurants of the new Hotel LaSalle. "Edelweiss" beer from the Peter Schoenhofen Brewing Company of Chicago was also served.

FIRE AT THE HOTEL LASALLE

Chicago Tribune, June 5, 1946.

The Hotel LaSalle in Chicago was booked solid on June 5, 1946, and its guests were mostly asleep, when a sprinkling of night owls in the Silver Grill Cocktail Lounge noticed the smell of burning wood. A patron and several employees squirted seltzer water and poured sand on the flames that emerged from beneath the bar's wood paneling, but it was in vain.

Arriving in the lobby about 12:30 a.m., night manager W.H. Bradfield saw fire shooting out of the bar and asked if the Fire Department had been called. "'We called them,' they told me, 'but we'll call them again,'" Bradfield recalled afterward to a Tribune reporter from a bed in Illinois Masonic Hospital.

Sixty-one died with approximately 60 injured, needing assistance out of the building, with another 150 patrons that reported a variety of injuries, but made it out of the hotel on their own in the disaster that was thought to be impossible. All the other guests, in the fully booked hotel, escaped without incident.

When it opened in 1909, the 22-story building at LaSalle and Madison streets was touted as "the most comfortable, modern and safest hotel west of New York City."

In fact, it was a tragedy waiting to happen, and made of chance and dereliction, compounded by mendacity.

Whatever Bradfield was told, the Fire Department got its first phone call at 12:35 a.m., about 15 minutes after the fire started — a delay that firefighters dread, knowing it can be deadly. A guest from Des Moines, Iowa, William Poorman, returned to the hotel a few minutes before that phone call and heard what sounded "like a gas explosion" as the lobby ceiling "lighted up almost immediately."

Arriving a few minutes later, Battalion Chief Eugene Freemon saw a wall of flames in the hotel lobby and knew he needed reinforcements. Today a firefighter would call in an extra alarm, but in 1946 radios were almost nonexistent in the Chicago Fire Department. Freemon's driver had to run to the nearest fire-alarm box and tap out 2-11 on the telegraph key inside.

Freemon led firefighters from Engine 40, Squad 1 and Hook and Ladder 6 on a search for victims. As they passed through the lobby, part of a mezzanine collapsed on them. They were rescued by arriving firefighters — eventually there would be 300 on the scene — but Freemon died of smoke inhalation.

By now the inferno, having fed on the two-story lobby's highly varnished woodwork, was moving up through the hotel's two staircases. Doors planned for each floor had never been installed, turning the stairwells from escape routes into chimneys, sucking smoke up into the corridors.

Subsequent investigations raised, but didn't answer, the question of how the hotel got away with such elementary safety violations. A police order had interrupted a 1935 remodeling of the Silver Lounge because combustible materials were being used. But the record showed the work had been resumed "by agreement."

As the inferno grew, Bradfield, the night manager, came across the hotel's operator at the switchboard, alerting guests. He urged her to get out. "No. I'm going to stay at my station," replied Julia C. Berry. There she died, having saved hundreds of lives, officials later said.

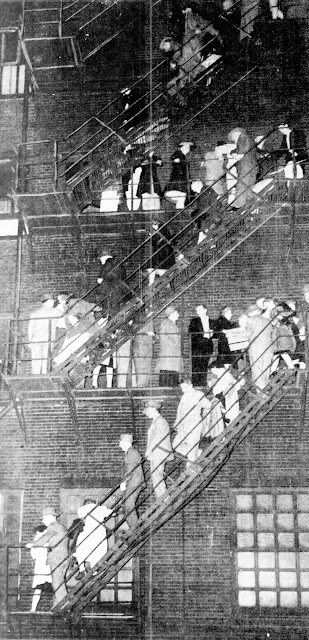

With the staircases unusable, firefighters saved guests by raising ladders to the windows of lower-floor windows. Those on upper floors had to be brought down via fire escapes, which luckily were in working order.

Tribune war correspondent Joseph Hearst and his wife had just returned from China and were in a room on the 19th floor. "Someone in the hall yelled for everyone to get out," he said. "We wrapped wet towels around our faces, felt our way down the corridor to the fire escape and descended safely."

A number of newly discharged servicemen staying at the hotel joined the rescue effort.

Seaman 1st Class Joseph O'Keefe, aided by three civilians, dragged 27 guests from fifth-floor rooms after discovering the hotel's fire hose was useless. "It just went drip, drip," he said. His buddy, Seaman 1st Class Robert Might, helped people down a fire escape before being overcome by smoke and taken to Henrotin Hospital. Two more sailors, Bernard Traska and Robert Higdon, dragged hose lines into the hotel and helped raise ladders.

Hotel LaSalle's Exterior Fire Escape

Fawn, a seeing-eye dog, guided her owner down a fire escape. "I can't see and I can't smell, but I tasted the smoke and nudged Fawn," said Anita Blair of El Paso, Texas. "We followed the crowd around a corner, and then a man helped me and my dog over the windowsill and onto a fire escape landing."

The Anti-Cruelty Society gave Fawn and Blair an award: "For exceptional kindness done by a human being to an animal, and the other way around," the Tribune reported.

The Chicago Telephone Traffic Union established a college fund for John Joseph Berry, the 16-year-old son of the operator who died while alerting others.

Merritt Penticoff and his wife spent an agonizing 45 minutes in their 18th-floor room before a knock on the door suggested it was safe to leave. "We got dressed after that pounding," Mrs. Penticoff said, as the Tribune reported, without using the woman's full name. "Then my husband laughed for the first time — I had automatically put on lip rouge, despite my haste, acting absolutely subconsciously."

Not everyone maintained his dignity or acted heroically. A fire marshal saw a firefighter looting rooms. A judge dismissed charges brought against him — a denouement that seemed fishy as he was a stepbrother of a Democratic ward committeewoman. Nonetheless, he resigned upon the discovery that he had lied about his age on his application to join the Fire Department.

Still, even thieves can have a guilty conscience. Jewelry worth $1,500 ($19,500 today) was taken during the fire from the 10th-floor room of Gertrude Cummings. Eleven days later, the jewelry was mailed to the hotel with a note saying: "Please return to owner."

Shortly, seven separate investigations were launched, some in hopes of preventing future disasters. Other inquiries were inspired, a Tribune editorial observed, by "the natural desire of politicians to get their names in the paper."

Blue-ribbon panels recommended reforms varying from stricter building codes to equipping all emergency vehicles with radios. But even the experts had to be reminded of perhaps the number-one rule of fire safety. During one hearing, the coroner agreed with the Hotel LaSalle's president that it wasn't necessary to call the Fire Department for every whiff of smoke or a few flames.

That was too much for Capt. Frank Thielman, a fire prevention investigator, who jumped up. "Delayed alarms cause loss of life," he shouted. "We have been preaching this for years and have fought a losing battle."

|

| People stick their heads out of the windows at the Hotel LaSalle during a June 5, 1946 fire. The Tribune wrote, "As flames shot as high as the seventh-floor level from the street, the loop echoed to the screams and cries of men and women standing at open windows." |

|

| Firefighters are on the scene. |

|

| Firefighters help a man in his bed during a fire at the Hotel LaSalle on June 5, 1946. |

|

| Policemen carry a victim out of the Hotel LaSalle on June 5, 1946, after a fire broke out at the Loop Hotel. |

|

| Crowds gather outside the Hotel LaSalle at Madison and LaSalle streets on the morning of June 5, 1946, after a significant fire at the hotel the night before. |

|

| The inside of the Hotel LaSalle on June 14, 1946, after a significant fire. The Tribune wrote, "Firemen rushed into the smoke-filled lobby and braved fierce flames that made the mezzanine, in the words of one witness, 'a hellish ball of fire.' Soon, firemen were carrying out unconscious guests, picked up in the smoke-filled corridors." |

|

| The lobby of the Hotel LaSalle on June 14, 1946, after the central fire. The Tribune wrote, "The conflagration left the ornate, walnut paneled lobby, and the mezzanine floor a charred and blackened wreck. Fire damage was severe as high as the fifth floor, particularly in corridors and areas adjacent to the stairways, which served as pathways for the flames and smoke." |

|

| The interior of the Hotel LaSalle after the central fire. |

|

| The interior of the Hotel LaSalle after the major fire. |

|

| The interior of the Hotel LaSalle after the major fire. |

Some Interesting Figures Presented In Chicago Fire Department's Consolidated Report.

When Fire Engineering's July account of the fatal Hotel LaSalle fire in Chicago on June 5, 1946, was written, many details of the fire department's operation needed to be included.

In as much as the actual working data of the Chicago Fire Department are, to the advanced firefighter, the most interesting, the editors secured the permission of Chief Fire Marshal Anthony Mullaney of the Chicago Fire Department to bring its readers that statistical story which was not available when the July account was prepared.

The fire was in the Hotel LaSalle, owned by Roanoke Realty Co. (LaSalle Madison Hotel Co.). The building was twenty-two stories in height with two basements. It was constructed of reinforced concrete and occupied an area of 178 x 162 feet.

The duration of the fire (fire department operations) was three hours and thirty-two minutes.

The number of persons killed (at the time of the report) was 61, with approximately 60 injured and 150 rescued.

The total number of alarms was seven.

The first notification of the fire department was a still alarm at 12:35 AM on June 5, 1946. This was followed by a box alarm from street firebox 1028. From that time on, the warnings and assignments were as follows:

Commissioner Corrigan was in charge of all operations. In command at the start of the fire: Division Marshal Gibbons. Upon his arrival, he ordered the 5-11 alarm struck and put companies to work on the Madison Street side of the hotel. He supervised companies' work until the arrival of 2nd Deputy Chief Haherkorn. Afterward, he went inside and proceeded up the stairs, overseeing the operations of various companies on various floors.

- 1st Alarm 12:38 A.M. (15 40 responded on the still alarm)

- 2nd Alarm 12:40 A.M.

- 3rd Alarm 12:45 A.M.

- 4th Alarm 12:45 A.M.

- 5th Alarm 12:45 A.M.

- SPECIAL CALLS

- (Special Duty) 1:08 A.M.

- (1st Special) 1:16 A.M.

- (2nd Special) 1:18 A.M.

- (Special Duty) 1:45 A.M.

- (Special Duty) 2:10 A.M.

The Chief officers present were 2nd Deputy Chief Haherkorn, 2nd Deputy Chief Dahl, Drillmaster Sheehan, 1st Deputy Chief Cody and Marshal Fenn, head of the Fire Prevention Bureau.

Operations of the four battalion chiefs at the fire are briefed as follows: Chief Freemon, 1st Battalion. (who died later in the hospital). Ordered a box, and 2-11 struck. Put companies to work on the east side of the building. Went inside on 4th, 5th, and 6th floors to evacuate occupants.

Chief Walsh, 25th Battalion: Supervised the working of hose streams on the LaSalle Street side. Also, the removal of bodies from various floors.

Chief Powers: Supervised the working of hose streams inside the 1st and 2nd floors. Also checked all the floors. Removed bodies from the 3rd floor.

Chief Bieze: Supervised the working of hose streams on the 2nd floor. Madison Street side; later directed streams on elevator shaft on all floors; led removal of bodies on all floors.

Forty Lines Stretched

The report indicated that 38 hose lines were stretched and charged during the period of operations, while two more were laid in but not charged. Four lines were Siamese. Five pumpers operated two lines; one worked three, and one (F 40) operated four. Approximately 4100 ft. of 3-in. hose and 15,700 ft. of 2 1/2-in Hose was stretched. Lengths of stretches varied from 100-ft. to 950 ft. The hydrants used were all the "Chicago" type. The distance of pumpers from the fire varied from 50 ft. (E 40 and 13) to 950 ft. (E 114),

The report indicates that first-in companies immediately hooked up to standpipes and stretched into the lobby. Hand lines were taken into the building over the hotel canopies and up ladders, including the department's most extended all-metal types. Other companies operated lines into elevator shafts, some using the building standpipes.

Running throughout the account of company operations is the phrase "Assisted in the removal of bodies" and "applied artificial respiration." After stretching in and hitting the fire, many engine company personnel applied artificial respiration to victims whom they encountered.

A few companies operated streams briefly, then worked to revive victims. Two engine companies stretched but did not charge lines.

With the ladder companies, as might be expected, the objectives were to save lives—to get the victims and the uninjured guests out of the building.

The structure was laddered on every side except the north, and some ladders were raised to corners. Every type and length of ladder in the department was used.

The accounts relate how companies rescued persons on floors up to and including the seventh and how firemen assisted guests down the fire escapes, opened up and searched rooms, located casualties and applied artificial respiration where a possible spark of life remained.

Likewise, the squads and special service forces' work primarily concerns rescue and resuscitation. Such terse company reports abound: "Evacuated Floors 4-5-6; Laddered North East Corner building."

"Rescued 6. Removed dead. Laddered West side of the building."

"Hand-line to the 3rd floor, and H & H on victims."

"Used body bags and stretchers to remove victims."

"Inhalator on the 3rd floor."

"E & J—H & H on victims 6th and 7th floors."

"Removed bodies from floors 3 to 11." "Inhalator on victims floors 5-7-8-21" (Indicating height to which people were overcome).

"Inhalator on victims floors 9-10-11."

One tragic item in the report catches the eye: "Used resuscitator on Chief Freemon—Removed to hospital."

The records indicate that most companies performed more than three hours of duty at the scene. One engine company operated for 4 hours, while a ladder company put in 28 hours and 40 minutes of work. A unique service unit (searchlight) reported 12 hours and 20 minutes worked.

The total period of operation by the fire department personnel reaches an impressive total of over 270 company hours.

The report attributes the discovery of the fire to an employee and indicates there was a delay in reporting the fire.

The fire communicated throughout part of the hotel using stairways and elevator shafts.

Weather data shows that the wind was "mild," the temperature was 60 deg., and it was a clear night.

Reporting on the condition of the building after the fire, the record says: "safe on upper floors. Lobby and stairways from 1st to 3rd full of debris and broken stair treads and frames."

Under the subject "lessons suggested by the fire," the report emphasizes that "open stairways cause the fire to spread." And it recommends: "enclosure of all stairways in this building occupancy."

The total number of fire department equipment of all types employed at the fire is given as follows: 33 engines (pumpers); 8 trucks (ladder units); 10 squads; 2 pressure wagons (Hand Pump. trucks); 2 water towers; 2 ambulances and 2 light wagons (searchlights).

Hotel Urged to Inspect

Discussing fire preventive measures in hotels notably, Fire Commissioner Frank B. Quayle of New York, speaking before the Eastern Association of Fire Chiefs, advocated cooperation between hotel management and fire departments and prompt transmitting of alarms when a fire is discovered. Smoke and panic were the most general causes of loss of life at such fires, he said, and he recommended the organization of hotel staff for systematic inspection of possible fire hazards and for the supervision of guests in case of an alarm for fire.

Following the fatal Hotel LaSalle fire in Chicago, Mayor O'Dwyer instructed Commissioner Quayle and heads of other responsible city agencies to intensify inspections of hotels and multiple dwellings in all city communities. Commissioner Quayle went on the air to urge closer cooperation between hotel management and the fire department to ensure excellent fire safety.

|

| Two North LaSalle Street, Chicago, Illinois. |