In historical writing and analysis, PRESENTISM introduces present-day ideas and perspectives into depictions or interpretations of the past. Presentism is a form of cultural bias that creates a distorted understanding of the subject matter. Reading modern notions of morality into the past is committing the error of presentism. Historical accounts are written by people and can be slanted, so I try my hardest to present fact-based and well-researched articles.

Facts don't require one's approval or acceptance.

I present [PG-13] articles without regard to race, color, political party, or religious beliefs, including Atheism, national origin, citizenship status, gender, LGBTQ+ status, disability, military status, or educational level. What I present are facts — NOT Alternative Facts — about the subject. You won't find articles or readers' comments that spread rumors, lies, hateful statements, and people instigating arguments or fights.

FOR HISTORICAL CLARITY

Fort Dearborn was built in 1803 at the mouth of the Chicago River in Chicago (Indian: Chicagoua / French: Chécagou / British: Chicago). It was constructed by troops under Captain John Whistler and named in honor of Henry Dearborn, then United States Secretary of War. The original Fort was destroyed following the Battle of Fort Dearborn during the War of 1812, and a new fort was constructed on the same site in 1816.

When I write about the INDIGENOUS PEOPLE, I follow this historical terminology:

- The use of old commonly used terms, disrespectful today, i.e., REDMAN or REDMEN, SAVAGES, and HALF-BREED are explained in this article.

Writing about AFRICAN-AMERICAN history, I follow these race terms:

- "NEGRO" was the term used until the mid-1960s.

- "BLACK" started being used in the mid-1960s.

- "AFRICAN-AMERICAN" [Afro-American] began usage in the late 1980s.

— PLEASE PRACTICE HISTORICISM —

THE INTERPRETATION OF THE PAST IN ITS OWN CONTEXT.

sidebar

"Fort Chécagou" is believed to be a French Fort built in 1685. I've done the research, so you decide if there was a French fort at the mouth of the Chicago River. Did Fort Chécagou, a French fort, exist at the mouth of the Chicago River at any time, or was it a myth?

THE FIRST FORT DEARBORN (1803-1812)

A Jesuit mission, the Mission of the Guardian Angel, was founded somewhere in the vicinity in 1696 but was abandoned around 1700. The Fox Wars effectively closed the area to Europeans in the first part of the 18th century. The first non-native to resettle in the area may have been a trader named Guillory, who might have had a trading post near Wolf Point on the Chicago River around 1778. Jean Baptiste Pointe de Sable (the "du" of Point du Sable is a misnomer. It is an American corruption of "de" as pronounced in French. "Jean Baptiste Pointe de Sable" first appears long after his death) and Choctaw (an Indian from the Great Lakes) built a cabin and trading post near the mouth of the Chicago River in the 1780s. Pointe du Sable is widely regarded as Chicago's first black and non-native settler.Antoine Ouilmette was the first permanent white settler of Chicago in July of 1790, building a cabin at the mouth of the Chicago River.

On March 9, 1803, Henry Dearborn, the Secretary of War, wrote to Colonel Jean Hamtramck, the commandant of Detroit, instructing him to have an officer and six men survey the route from Detroit to Chicago and to make a preliminary investigation of the situation at Chicago. Captain John Whistler was selected as commandant of the new post and set out with six men to complete the survey. The survey was conducted on July 14, 1803, a company of troops set out to make the overland journey from Detroit to Chicago.

|

| The American Flag reportedly was flown at Fort Dearborn. 1803-1812. |

|

| Plan of the First Fort Dearborn, drawn by Captain John Whistler in 1808. CLICK FOR A FULL-SIZED MAP |

|

| The location of Fort Dearborn is superimposed on today's street grid. |

|

| Illustration of Fort Dearborn - 1804 |

|

| The Chicago River before being straightened in 1855. |

|

| Model of the first Fort Dearborn (1803-1812) from a drawing made in 1808 by Captain John Whistler. Sculpted by A. L. Van Den Berghen, 1898. |

Kinzie rapidly became the civilian leader of the small settlement that grew around the Fort. Still, Kinzie was said to be an "aggressive" trader and was described as a "volatile and violent character" who clashed with some American soldiers stationed at Fort Dearborn.

sidebar

The Chronology of the Kinzie House, Chicago.

In the spring of 1782, possibly earlier, Jean Baptiste Pointe de Sable settled at Chicago to farm and trade with the Indians. He built a crude log cabin in 1784 on the west bank of the north branch of the Chicago River (the north branch was then named the Guarie River), just north of where the river turned east to meet the lake. Pointe de Sable farmed and traded with the Indians.

Jean Baptiste Pointe de Sable's 1784 farm is recognized as the first settlement he called “Eschikagou ►" on the north branch of the Chicago River, known as the Guarie River.

Pointe de Sable's second house became known as the Kinzie Mansion. Antoine Ouilmette's house is seen in the background. Illustration from 1827. Pointe de Sable built a second trading post/cabin on the north side of the Chicago River, very close to the river's mouth. By the time he sold the second cabin (illustration) in 1800 for 6,000 Livres ($1,200), he had developed the property into a commodious, well-furnished French-style house with numerous outbuildings.The Wayne County Register of Deeds in Detroit—Chicago was part of that county during Northwest Territory days—debunks many of the Kinzies’ claims. Their records show Jean Lalime, not Joseph Le Mai, bought Ponte de Sable’s trading post in 1800, bankrolled by Lalime and Kinzie’s mutual boss, fur trader William Burnett. There COULD NOT have been confusion because Kinzie signed the deed as a witness.Successive owners and occupants include:

- Jean Lalime & William Burnett: 1800-1803, owner. (A careful reading of the Pointe de Sable-Lalime sales contract indicates that William Burnett was not just signing as a witness, but also financing the transaction, therefore he had controlling ownership.)

- John Kinzie's Family: 1804-1828 (except during 1812-1816).

- Widow Leigh & Mr. Des Pins: 1812-1816.

- John Kinzie's Family: 1817-1829.

- Anson Taylor: 1829-1831 (residence and store).

- Dr. E.D. Harmon: 1831 (resident & medical practice).

- Jonathan N. Bailey: 1831 (resident and post office).

- Mark Noble, Sr.: 1831-1832.

- Judge Richard Young: 1832 (circuit court).

- Unoccupied and decaying by 1832.

- Nonexistent by 1835.

In 1810 Kinzie and Whistler became embroiled in a dispute over Kinzie supplying alcohol to the Indians. In April, Whistler and other senior officers at the Fort were removed; Whistler was replaced as commandant of the Fort by Captain Nathan Heald.

One of the buildings Pointe de Sable had built was the area's first bakery that supplied Fort Dearborn with fresh bread.

The Fort Dearborn Massacre was partially due to the attack by Indians at Charles Lee's Place. On April 6, 1812, a party of ten or twelve Winnebagoes, dressed and painted, arrived at the Lee house and, according to the custom among savages [1], entered and seated themselves without ceremony. What happened next was horrific; this incident was the precursor to the Fort Dearborn Massacre later that summer.

Jean B. La Lime, John Kinzie's neighbor, was Chicago's first murder victim. Tensions between Kinzie and La Lime came to a head on June 17, 1812, when the two men met outside Fort Dearborn. La Lime was armed with a pistol and Kinzie with a butcher's knife. There was a witness account.

|

| Civilian Residence Around Fort Dearborn Before the Massacre. |

THE FORT DEARBORN MASSACRE

Among the many significant blunders made by the Madison administration in 1812 was its failure to tell the frontier that it was about to declare war on Great Britain. As a result, the British and Indians knew several days before the Americans that hostilities had broken out.

At the beginning of the War of 1812, Captain Wells was in command at Fort Wayne. When he heard of General Hull's orders for the evacuation of Fort Dearborn, he made a rapid march with several friendly Indians to assist in defending the Fort or to prevent its exposure to certain destruction or by an attempt to reach Fort Wayne in safety at the head of the Maumee with the men, women, and children of old Fort Dearborn.

Toward the evening of August 7, 1812, the Wen-ne-meg or the "Catfish," friendly Potawatomi Chief, who was intimate with John Kinzie, came to Fort Dearborn from Fort Wayne as the bearer of a dispatch from General Hull to Captain Nathan Heald, in which the former announced his arrival at Detroit with an army, the declaration of war, the invasion of Canada, and the loss of Mackinack. It also conveyed an order to Captain Heald to evacuate Fort Dearborn, if practicable, and to distribute in that event all the United States property contained in the Fort and in the government factory or agency in the neighborhood. This was doubtless intended to be a peace offering to the savages [1] to prevent them from joining the British then menacing Detroit.

Wenemeg, who knew the purport of the order, begged Mr. Kinzie to advise Captain Heald not to evacuate the Fort, for the movement would be difficult and dangerous.

The Indians had already received information from Tecumseh of the disasters to the American arms and the withdrawal of Hull's army from Canada. They were becoming more restless and insolent daily.

Heald had ample ammunition and provisions for six months; why not hold out until relief could come from the southward? Winemeg further urged that if Captain Heald should resolve to evacuate, it should be done immediately before the Indians should be informed of the order or could prepare for formidable resistance. "Leave the fort and stores as they are," he said, "and let them make the distributions for themselves, and while the Indians are engaged in that business, the white people may make their way safely to Fort Wayne." Mr. Kinzie readily perceived the wisdom of Winemeg's advice, and so did Captain Heald's officers—but the Commander blindly resolved to obey Hull's order strictly as to evacuation and the distribution of the public property. He caused that order to be read to the troops on the morning of the 8th and then assumed responsibility.

His officers expected to be summoned to a council but were disappointed. Toward evening they called upon the Commander, and they remonstrated with him when informed of his determination. They said the march must be slow on account of the women, children, and infirm persons and, therefore, under the circumstances, extremely perilous. Hull's orders, they said, left it to the discretion of the Commander to go or stay, and they thought it much better to strengthen the Fort, defy the savages and endure a siege until relief should reach them.

Heald argued in reply that special orders had been issued by the war department, that no post should be surrendered without battle having been given by the assailed, and that his force was totally inadequate for an engagement with the Indians. He said he should expect the censure of his government if he remained, and having complete confidence in the professions of the friendship of many of the Chiefs about him, he should call them together, make the required distributions and take up his march for Fort Wayne. After that, his officers had no more communication with him on the subject.

With fatal procrastination, the Indians became more unruly every hour, yet Heald postponed assembling the savages for two or three days. They finally met near the Fort on the afternoon of the 12th, and the Commander held a farewell council with them there. Heald invited the officers to join him in the council, but they refused. They had received intimations that treachery was designed, that the Indians intended to murder them in the council circle and then destroy the inmates of the Fort. The officers remained within the pickets and opened the port of one of the blockhouses to expose the cannon pointed directly upon the group in the council. They secured the safety of Captain Heald. The Indians were intimidated by the menacing monster and accepted Heald's offers with many protestations of friendship.

He agreed to distribute among them not only the goods in the general store, blankets, broadcloths, calicoes, paints, etc., but also the arms, ammunition, and provisions not necessary for the use of the garrison on its march. It was stipulated that the distribution should occur the next day, after which the garrison and white inhabitants would leave the works. The Pottawattomies agreed on their part to furnish a proper escort for them through the wilderness to Fort Wayne on the condition of being liberally rewarded on their arrival there.

When the result of the council was made known, John Kinzie warmly remonstrated with Captain Heald. He knew the Indians well and their weakness, in the presence of great temptations, to do wrong. Kinzie begged the Commander not to confide in their promises at the moment so inauspicious for faithfulness to treaties. He especially entreated him not to place in their hands firearms and ammunition, for it would fearfully increase their power to carry on those murderous raids, which for months had spread terror throughout the frontier settlements.

Heald perceived his folly and resolved to violate the treaty so far as arms and ammunition were concerned. On that very evening, when the Chief of the council seemed most friendly, a circumstance that should have made Captain Heald shut the gate to his dusky neighbors and resolve not to leave the Fort.

Black Partridge, a hitherto friendly Potawatomi Chief and a man of much influence, came quietly to the Commander and said: "Father, I came to deliver to you the medal I wear. It was given to me by the Americans, and I have long worn it as a token of our mutual friendship. But our young men are resolved to imbrue their hands in the blood of the white people. I cannot restrain them and will not wear a token of peace while I am compelled to act as an enemy." This solemn and authentic warning was strangely unheeded.

The morning of the 13th was bright and cool. The Indians assembled in great numbers to receive their presents, but nothing save the goods in the store were distributed that day. In the evening, Black Partridge said to Mr. Griffith, the interpreter, "Linden birds have been singing in my ears today; be careful on the march you are going to take." This was another solemn warning which was communicated to Captain Heald. It, too, was unheeded; and at midnight, when the sentinels were all posted, and the Indians were in their camps, a portion of the powder and liquor in the Fort was cast into a well near the sally port, and the remainder into a canal that came up from the river far under the covered way. The muskets not reserved for the garrison were broken up, and these, with shots, bullets, flints, gun screws, and everything else pertaining to firearms, were also thrown into the well.

A large quantity of alcohol belonging to John Kinzie was poured into the river, and before morning the destruction was complete. But the work had not been done in secret. The night was dark, and vigilant Indians had crept to the Fort as noiselessly as serpents, and their quick senses had perceived the destruction of what they claimed as their own under the treaty.

In the morning, the work of the night was made more manifest. The powder was seen floating upon the surface of the river, and the sluggish water had been converted by whiskey and the alcohol into strong grog, as an eyewitness remarked.

Complaints and threats were loud among the savages because of this breach of faith. The dwellers in the Fort were impressed with the dreadful sense of impending destruction when the brave Captain Wells, Mrs. Heald's uncle and adopted son of the Chief Little Turtle, was discovered upon the Indian trail near the sandhills on the border of the lake not far distant, with a band of mounted Miamis of whose tribe he was considered a Chief.

He had heard at Fort Wayne of the orders of Hull to evacuate Fort Dearborn, and being fully aware of the hostilities of the Potawatomi, he had made a rapid march across the country to reinforce Captain Heald, assist in defending the Fort or prevent its exposure to certain destruction by an attempt to reach the head of the Maumee, but he was too late. All means for maintaining a siege had been destroyed a few hours before, and every preparation had been made for leaving the post the next day.

When the morning of the 15th arrived, there were positive indications that the Indians intended to massacre all the white people. They were overwhelming in numbers and held the fate of the devoted band in their grasp. When at nine o'clock, the appointed hour, the march commenced. It was like a funeral procession.

|

| The Fort Dearborn Massacre was on August 15, 1812. Painting by Samuel Page. The painting represents Mrs. Helms being rescued from her would-be slayer Naunongee by Black Partridge. To her left is Surgeon Van Voorhes falling mortally wounded. Other characters depicted are Capt. William Wells, Mrs. Heald on horseback, Ensign Ronan, Mrs. Ronan, Mrs. Holt, Mr. John Kinzie, and Chief Waubonsie. In the background are Indians, the wagons containing children, and the boat on the lake bearing Kinzie's family to safety. |

The treacherous and cowardly Potawatomi had made those hillocks their cover for a murderous attack. The troops hastily brought into line charged up the bank when one of their number, a white-haired man of seventy years, fell dead from his horse, the first victim. The Indians were driven back, and the battle was waged on the open prairie between fifty-four soldiers, twelve civilians, and three or four women against about five hundred Indian warriors. Of course, the conflict was hopeless on the part of the white people, but they resolved to make the butchers pay dearly for every life they destroyed.

The cowardly Miamis fled at the first onset. Their Chief rode up to the Potawatomi, charged them with perfidy, and, brandishing his glittering tomahawk, declared that he would be the first to lead Americans to punish them. He then wheeled and dashed after his fugitive companions, who were scurrying over the prairies as if the evil Spirit were at their heels. The conflict was short, desperate, and bloody. Two-thirds of the white people were slain or wounded, all the horses, provisions, and baggage were lost, and only twenty strong men remained to brave the fury of about five hundred Indians, who had lost but fifteen in the conflict. The devoted band had succeeded in breaking through the ranks of the assassins who gave way in front, rallied on the flank, and gained a slight eminence on the prairie near a grove called the oak woods.

The savages did not pursue it. They gathered upon the sandhills in consultation and gave signs of willingness to parley.

Further conflict with them would be rashness, so Captain Heald, accompanied by Parish, the Clerk, a half-breed [1] boy in John Kinzie's service, went forward, met Blackbird on the open prairie, and arranged terms for a surrender. It was agreed that all the arms should be given up to Blackbird and that the survivors should become prisoners of war, to be exchanged for ransoms as soon as practicable; with this understanding, captured and captors all started for the Indian encampment near the Fort. So overwhelming was the savage force at the sandhills was so overwhelming that the conflict after the first desperate charge became an exhibition of individual prowess, a life-and-death struggle in which no one could assist his neighbor, for all were principles. In this conflict, women bore a conspicuous part. All fought gallantly so long as strength permitted them. The brave ensign, Ronan, wielded his weapon even when falling to his knees because of blood loss.

Captain Wells displayed the greatest coolness and gallantry. He was by the side of his niece when the conflict began. "We have not the slightest chance for life," he said. "We must part to meet no more in this world. God bless you, my child." With these words, he dashed forward with the rest. Amid the fight, he saw a young warrior, painted like a demon, climb into a wagon where twelve children of the white people were and tomahawked them all. Forgetting his immediate danger, Wells exclaimed, "If that is your game, butchering women and children, I'll kill too." He instantly dashed toward the Indian camp where they had left their squaws and little ones, hotly pursued by swift-footed young warriors, who sent many rifle balls after him. He lay close to his horse's neck and turned and occasionally fired upon his pursuers; when he had got almost beyond the range of their rifles, a ball killed his horse and wounded him severely on the leg. The young savages rushed forward with a demoniac yell to make him a prisoner and reserve him for torture, for he was to them an arch offender.

His friends, Winnemeg and Wanbansee, vainly attempted to save him from his fate. He knew the temper and practices of the savages well and resolved not to be made captive. He taunted them with the most insulting epithets to provoke them to kill him instantly. At length, he called one of the fiery young warriors (Persotum) a Squaw, which so enraged him that he killed Wells instantly with a tomahawk, jumped upon his body, cut out his heart, and ate a portion of the warm and half palpitating morsel with savage delight.

sidebar

Alexander Robinson (aka Che-che-pin-quay or 'The Squinter'), was a British-Ottawa chief born on Mackinac Island who became a fur trader and ultimately settled near what later became Chicago. Multilingual in Odawa, Potawatomi, Ojibwa (Chippewa), English and French, Robinson helped evacuate survivors.Captain William Wells, taken captive by Miami & Delaware Indians at 13 years old, was an Indian warrior but fought for the U.S.Believe it or not, most of Billy Caldwell's history was fabricated. Caldwell claimed to have arrived on the scene just after the battle and saved the lives of John Kinzie and his family, but historians have been unable to verify it.

The wife of Captain Heald, who was an expert with the rifle and an excellent equestrian, deported herself bravely. She received severe wounds, but faint and bleeding, she managed to keep the saddle. A savage raised his tomahawk to kill her when she looked him full in the face and, with a sweet, melancholy smile, said in the Indian tongue, "Surely you will not kill a squaw." The appeal was effective. The arm of the savage fell, and the life of the heroic woman was saved. Mrs. Helm, the stepdaughter of Mr. Kinzie, had a severe personal encounter with a stalwart young Indian who attempted to tomahawk her. She sprang to one side and received the blow intended for her head upon her shoulder, and at the same instant, she seized the savage around the neck and endeavored to get hold of his scalping knife, which hung in a sheath upon his breast. While thus struggling, she was dragged from her antagonist by another Indian, who bore her, despite her desperate resistance, to the margin of the lake and plunged in at the same time, to her astonishment, holding her so that she would not drown. She soon perceived she was held by a friendly hand. It was Black Partridge who had saved her. When the firing ceased and capitulation was concluded, he conducted her to the prairie where she met her father and heard her husband was safe. Bleeding and suffering, she was led to the Indian camp by Black Partridge and Persotum, the latter carrying in his hand a scalp which she knew to be that of Captain Wells by the black ribbon that bound the queue. The wife of a soldier named Gorford, believing that all prisoners were reserved for torture, fought desperately and suffered herself to be literally cut in pieces rather than surrender.

The wife of Sergeant Holt, who was severely wounded in his neck at the beginning of the engagement, received from him his sword and behaved as bravely as any Amazon. She was a large and powerful woman and rode a fine, high-spirited horse, which the Indians coveted. Several of them attacked her with the butt of their guns to dismount her, but she used her sword so skillfully that she foiled them. She suddenly wheeled her horse and dashed over the prairie, followed by a large number who shouted, "The brave woman! Brave woman! Don't hurt her!" They finally overtook her, and while two or three were engaging her in front, a powerful savage seized her by the neck and dragged her back to the ground. The horse and woman became prizes. The latter was afterward ransomed.

When the captives were taken to the Indian camp, a new scene of horrors was opened; the wounded, according to the Indian's interpretation of the capitulation, were not included in terms of surrender.

Proctor had offered a liberal sum for scalps delivered at Maiden. So nearly all the wounded men were killed, and the value of British bounties, sometimes offered for wolves' destruction, was taken from each head.

In this tragedy, Mrs. Heald played a part but fortunately escaped scalping. To save her fine horse, the Indians had aimed at the rider. Seven bullets took effect upon her person. Her captor, who was about to slay her upon the battlefield, as we have seen, left her in the saddle and led her horse toward the camp. When insight of the Fort, his inquisitiveness overpowered his gallantry, and he was taking her bonnet off her head to scalp her when she was discovered by Mrs. Kinzie, who was yet sitting in the boat, and who had heard the tumult of the conflict; but without any intimation of the result, until she saw the wounded woman in the hands of her savage captive. "Run! Run! Chandonnai!" exclaimed Mrs. Kinzie to one of her husband's clerks, standing on the beach. "That is Mrs. Heald. He is going to kill her! Take that mule and offer it as a ransom." Chandonnai promptly obeyed and increased the bribe by offering two bottles of whiskey. These were worth more than Proctor's bounty, and Mrs. Heald was released. She was placed in Mrs. Kinzie's boat and concealed from the prying eyes of other scalp hunters. Toward evening the family of Mr. Kinzie was allowed to return to their own house, where they were greeted by the friendly Black Partridge. Mrs. Helm was placed in the house of Antoine Louis Ouilmette, a Frenchman, by the same friendly hand.

But these and all the other prisoners were exposed to great jeopardy by the arrival of a band of fierce Potawatomi from the Wabash, who yearned for blood and plunder. They searched the houses for prisoners with keen vision. When no further concealment and safety seemed possible, some friendly Indians arrived and so turned the tide of affairs that the Wabash savages were ashamed to own their bloodthirsty intentions.

In this terrible tragedy in the wilderness, twelve children, all the masculine civilians but John Kinzie and his sons, Captain Wells, Surgeon Van Vorhees, Ensign Ronan, and twenty-six private soldiers, were murdered. Wells was shot and killed by the Potawatomi, who decapitated him and ate his heart. Despite considering him a traitor to their cause, his opponents nonetheless sought to gain some of his courage by consuming his heart.

The prisoners were divided among the captors and were finally reunited or restored to their friends and families. Of all the sad tragedies to which human life is susceptible, none surpassed that of the death of Captain William Wells. In its rich vocabulary, the English language fails to adequately express the courage and heroism this little band of men and women manifested on that fateful Saturday morning of August 15, 1812. The day dawned clear and warm, and as Seymour Curry tells us in his "Story of Old Fort Dearborn," scarcely a breath of air was stirring. The lake, unruffled, stretched away in a sheet of burnished gold. But the gold which shown most brilliant on that fateful day was that of this immortal band, which towered to the hall of fame.

The names and fate of the regular soldiers of the Fort Dearborn garrison on the morning of August 15, 1812:

1. Nathan Heald · Captain - returned to civilization

2. Lina T. Helm · 2nd Lieutenant - returned to civilization

3. George Ronan · Ensign - killed in battle near the baggage wagons

4. Isaac Van Voorhis · Surgeon's mate - killed in battle near the baggage wagons

1. Isaac Holt · Sergeant - killed in battle

2. Otho Hays · Sergeant - killed in battle in an individual duel with Indian

3. John Crozier · Sergeant - returned to civilization

4. William Griffith · Sergeant - returned to civilization

1. Thomas Forth · Corporal - killed in battle

2. Joseph Bowen · Corporal - returned to civilization

1. George Burnett · Fifer - killed in battle

2. John Smith · Fifer - returned to civilization

3. Hugh McPherson · Drummer - killed in battle

4. John Hamilton · Drummer - killed in battle

1. John Allin · Private - killed in battle

2. George Adams · Private - killed in battle

3. Prestly Andrews · Private - killed in battle

4. James Corbin · Private - returned to civilization

5. Fielding Corbin · Private - returned to civilization

6. Asa Campbell · Private - killed in battle

7. Dyson Dyer · Private - returned to civilization

8. Stephen Draper · Private - killed in battle

9. Daniel Daugherty · Private - returned to civilization

10. Micajah Denison · Private - badly wounded in battle; tortured to death the ensuing night

11. Nathan Edson · Private - returned to civilization

12. John Fury · Private - badly wounded in battle; tortured to death the ensuing night

13. Paul Grummo · Private - returned to civilization

14. Richard Garner · Private - tortured to death the night after the massacre

15. William N. Hunt · Private - frozen to death in captivity

16. Nathan A. Hurtt · Private - killed in battle

17. Rhodias Jones · Private - killed in battle

18. David Kennison · Private - returned to civilization; died in Chicago, 1852

19. Samuel Kilpatrick · Private - killed in battle

20. John Kelso · Private - killed in battle

21. Jacob Landon · Private - killed in battle

22. James Latta · Private - tortured to death the night after the massacre

23. Michael Lynch · Private - badly wounded; killed by the Indians en route to the Illinois River

24. Hugh Logan · Private - tomahawked in captivity because unable to walk from fatigue

25. Frederick Locker · Private - killed in battle

26. August Mortt · Private - tomahawked in captivity

27. Peter Miller · Private - killed in battle

28, Duncan McCarty · Private - returned to civilization

29. William Moffett · Private - killed in battle

30. Elias Mills · Private - returned to civilization

31. John Needs · Private - died in captivity

32. Joseph Noles · Private - returned to civilization

33. Thomas Poindexter · Private - tortured to death the night after the massacre

34. William Prickett · Private - killed in battle

35. Frederick Peterson · Private - killed in battle

36. David Sherror · Private - killed in battle

37. John Suttenfield · Private - badly wounded; killed by the Indians while en route to Illinois River

38. John Smith · Private - returned to civilization

39. James Starr · Private - killed in battle

40. John Sunmons · Private - killed in battle

41. James Van Horn · Private - returned to civilization

Believe it or not, most of Billy Caldwell's history was fabricated. Caldwell claimed to have arrived on the scene just after the battle and saved the lives of John Kinzie and his family, but historians have been unable to verify it.

The Potawatomi burned the Fort to the ground the next day.

NOTE: The account by Susan Simmons Winans (1812-1900), the last known survivor of the Chicago Fort Dearborn massacre as told to her by her mother. (Printed in the Sunday, December 27, 1896 Chicago Tribune.)

|

| Remaining Civilian Residence After the Fort Dearborn Massacre. |

THE FORT DEARBORN CEMETERY (Circa 1805-1835)

"Common Burial Ground at Fort Dearborn and Garrison Cemetery."

The dead from the surprise Indian attack was not buried, and their bones lay in the sand where they were killed until four years later, in 1816, when Fort Dearborn was reopened. They were reburied at the Common Burial Ground at Fort Dearborn, also referred to as Fort Cemetery or Garrison Cemetery.

One account says that victims were left as they laid near what would now be 18th Street and Calumet Avenue on Chicago’s near south side. The site was described as being on 18th Street, between Prairie (300 east) and Lake Michigan.

A second possible location was by Mrs. George W. Pullman’s house (1729 South Prairie) or the Northeast corner of 18th Street and Prairie Avenue in the South Township Section: SW 1/4 22 Township 39 Range: 14. This is about where the massacre took place and where victims were buried. Another source states that the site was just behind the Pullman mansion. The Pullman three-story mansion was built in 1873 and was valued at $500,000 in 1880 ($13.3 million today), but was razed in 1922.Another report suggests that the massacre burials were at what would now be 18th street and Calumet Avenue (325 east). Still another source states that the massacre was centered just east of what is now Prairie Avenue between 16th and 17th Streets.Still another account statesin 18th street, near Fernando Jones house (1834 South Prairie), is a spot supposed to contain the bodies of some two score (40 souls), while for several blocks along the lakeshore, it is said, graves were scraped into the land.

Historical accounts state that his first task was to carefully gather and bury the bones in what would later be called the Fort Dearborn Cemetery.

Fort Dearborn Cemetery can well be considered Chicago's first cemetery. Minimal physical descriptions of Fort Cemetery are known, but we know the site was not much more than sand, which shifted with the winds off Lake Michigan. It was difficult, if not impossible, to maintain the graves against the elements. Markers, at best, were probably simple wooden boards or crosses. Many other graves probably went unmarked.

Cutting through the sandbar for the harbor caused the lake to encroach and wash away the earth, exposing coffins and their contents, which were afterward cared for and reinterred by the civil authorities.

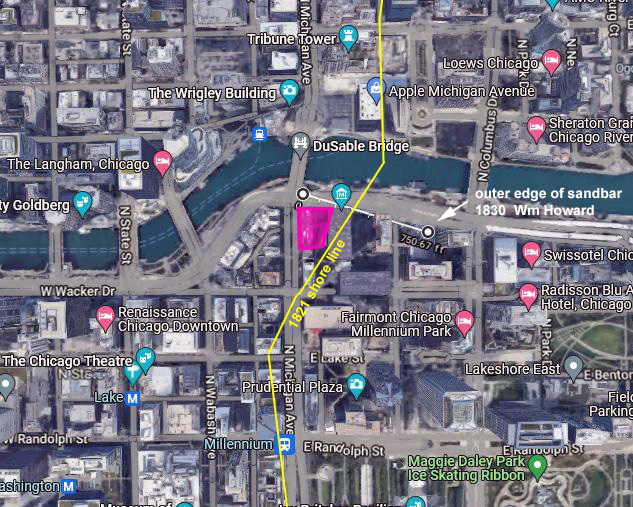

Located southeast of Fort Dearborn, the Common Burial Grounds at Fort Dearborn was found between the road leading to the Fort and the west bank of the Chicago River as it flowed southward to the lake, and it was before the channel was cut. According to modern street grids, the cemetery would have been south and east of the intersection of Lake Street (200 north) and Wabash Avenue (50 east). It was located on what today would be the south end of the Michigan Avenue bridge at the Chicago River (Approx. 300 N. Michigan by today's street numbering system).

Although there might have been an earlier burial, the first grave at the Fort other than Indian burials is that of Eliza Dodemead Jouett in 1805, wife of Charles Jouett (1772-1834), the first Indian agent and government factor at Chicago. Her grave was placed at the entrance to the garden of the Fort. Eliza of Detroit married Charles on January 22, 1803, and had one daughter. After Eliza's death, Charles remarried in 1809 and had one son and three daughters with his second wife.

On modern-day street grids, Eliza's grave would be in the middle of South Water Street (Wacker Place – 300 north) between Wabash Avenue (50 east) and Michigan Avenue (100 east). Although the special significance of her grave, by its location and identification on the Harrison map (marked in yellow), is not well explained, her death probably occurred before the formal beginning of the cemetery at the Fort.

|

| 1830 map drawn by F. Harrison Jr., U.S. Civil Engineer and approved by William Howard, U.S. Civil Engineer. The Fort Dearborn Cemetery is highlighted in green. |

The Fort Dearborn cemetery probably closed in 1835 when two regular cemeteries were established near Lake Michigan, at the edges of town. One was located on Chicago Avenue, and the other on Twelfth Street.

THE SECOND FORT DEARBORN (1816-1836)

Following the war, a second Fort Dearborn was built in 1816. This Fort consisted of a double wall of wooden palisades, officer and enlisted barracks, a garden, and other buildings. |

| Fort Dearborn was Rebuilt in 1816. |

This temporary abandonment lasted until 1828, when it was re-garrisoned following the outbreak of war with the Winnebago Indians. In her 1856 memoir Wau Bun, Juliette Kinzie described the Fort as it appeared on her arrival in Chicago in 1831:

The fort was inclosed by high pickets, with bastions at the alternate angles. Large gates opened to the north and south, and there were small portions here and there for the accommodation of the inmates. Beyond the parade-ground which extended south of the pickets, were the company gardens, well filled with currant-bushes and young fruit-trees. The fort stood at what might naturally be supposed to be the mouth of the river, yet it was not so, for in these days the latter took a turn, sweeping round the promontory on which the fort was built, towards the south, and joined the lake about half a mile below.

FORT DEARBORN LIGHTHOUSES

An Act of Congress established a lighthouse at Fort Dearborn on March 3, 1831. Samuel C. Lasby was the first keeper. It toppled over in October 1831, 10 months after the lighthouse was completed. A new conical stone lighthouse tower was swiftly constructed. |

| The original lighthouse at Fort Dearborn lighthouse collapsed in 1831, and it was replaced by this conical stone lighthouse in 1832. Description circa 1838. |

The Fort was closed briefly before the Black Hawk War of 1832, and by 1837, the Fort was being used by the Superintendent of Harbor Works. In 1837, the Fort and its reserve, including part of the land that became Grant Park, were deeded to Chicago by the Federal Government.

The First Presbyterian Church of Chicago was formed on June 26,1838, inside the walls of Fort Dearborn. Twenty-six members made up the first congregation, and 16 soldiers were stationed at the garrison.

In 1855 part of the Fort was demolished so that the south bank of the Chicago River could be dredged, straightening the bend in the river and widening it by about 150 feet.

The Chicago Fire of 1857 destroyed nearly all the remaining buildings in the Fort.

By the Civil War (1861-1865), Fort Dearborn's remaining blockhouse and few surviving outbuildings were being used by the Harbor Master of Chicago.

Everything that was left was destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

The site of Fort Dearborn is a Chicago Landmark by the Michigan–Wacker Historic District.

•••1803 April - Captain John Whistler, First Infantry, arrives at the mouth of the Chicago River from Detroit with six soldiers to survey the site and predetermine the construction of a fort on orders from General Henry Dearborn, Secretary of War.

•••1803 August 17 to 1810 - Captain Whistler returns in the company of his wife, three children, and 68 military personnel. He designed and built Fort Dearborn, becoming the first commandant; when cold weather arrived late in 1803, the troops were modestly sheltered.

•••1810 to 1812 August 15 - Captain Nathan Heald is named commandant.

•••1810 November to 1811 June - Lieutenant Philip Ostrander serves as acting commandant during Captain Heald's nine-month furlough.

•••1812 August 9 - Captain Heald receives orders from General Hull to evacuate the post and to remove its occupants to Detroit.

•••1812 August 15 - The Fort Dearborn Massacre occurs one and one-half miles south of the Fort as the garrison moves out. Four to five hundred Potawatomi attacked, killing 52 soldiers and civilians. Fifteen Indians are slain in action. Captain Heald survives.

•••1812 August 16 - Indians burn the Fort.

•••1816 July 4 to 1817 May - Captain Hezekiah Bradley, Third Infantry, arrives from Detroit with a garrison of 112 men; he designs and builds the second Fort Dearborn and becomes its first commandant.

•••1817 May to 1820 June - Brevet Major Daniel Baker, Third Infantry, Commandant

•••1820 June to 1821 January - Captain Hezekiah Bradley, Third Infantry, Commandant

•••1821 January to 1821 October - Major Alexander Cummings, Third Infantry, Commandant

•••1821 October to 1823 July - Lieutenant Colonel John McNeil, Third Infantry, Commandant

•••1823 July to 1823 October - Captain John Greene, Third Infantry, Commandant

•••1823 October to 1828 October 3 - Fort Dearborn remains unoccupied and is left in the care of Indian agent, Dr. Alexander Wolcott.

•••1828 October 3 to 1830 December 14 - Brevet Major John Fowle, Fifth Infantry, Commandant

•••1830 December 14 to 1831 May 20 - First Lieutenant David S. Hunter, Fifth Infantry, Commandant

•••1831 May 20 to 1832 June 17 - Fort Dearborn remains unoccupied and is left in the care of Indian agent Thomas J.V. Owen. A portion of the structure serves as a general hospital after July 11, 1831.

•••1831 - The U.S. Congress appropriates $5000 for the construction of a lighthouse which is built within the year near the N.W. corner of the stockade. The lighthouse collapsed soon after completion, and a new, sturdier one was erected in 1832.

•••1832 June 17 to 1833 May 14 - Major William Whistler, Second Infantry, Commandant [son of Captain John Whistler]

•••1833 May 14 to 1833 June 19 - Captain and Brevet Major John Fowle, Fifth Infantry, Commandant

•••1833 June 19 to 1833 October 31 - Major George Bender, Fifth Infantry, Commandant

•••1833 October 31 to 1833 December 18 - Captain DeLafayette Wilcox, Fifth Infantry, Commandant

•••1833 December 18 to 1835 September 16 - Major John Greene, Fifth Infantry, Commandant

•••1835 September 16 to 1836 August 1 - Captain DeLafayette Wilcox, Fifth Infantry, Commandant

•••1836 May 28 - Jean Baptiste Beaubien, a colonel in the Militia of Cook County, purchases land that contains the Fort Dearborn Reservation, including the Fort, for $94.61 from the U.S. Land Office in Chicago and receives a certificate. The U.S. Government later contests the sale.

•••1836 July - Colonel Beaubien's lawyer, Murray McConnell, brings legal action of ejection from the Fort against the commandant, Captain DeLafayette Wilcox.

•••1836 August 1 - Captain and Brevet Major Joseph Plympton, Fifth Infantry, replaces Captain Wilcox as Commandant.

•••1836 December 29 - Troops are permanently withdrawn from Fort Dearborn. Only Ordinance-Sergeant Joseph Adams and Captain Plympton remain responsible for Government property.

•••1837 May - Captain Plympton, last commandant, leaves the Fort; Captain Louis T. Jamison remains until late autumn, detailed on recruiting service.

•••1839 March - U.S. Supreme Court vacates Colonel Beaubien's purchase of Fort Dearborn.

•••1839 June 20 - Fort Dearborn Reservation, divided into blocks and lots by order of the Secretary of War, is sold to multiple private parties for the highest bids; receipts total $106,042.00.

•••1840 December 18 - Colonel Beaubien surrenders his certificate of purchase for Fort Dearborn, and the purchase price of $94.61 is returned to him.

•••1856 - Alexander Hesler photographs the abandoned Fort that has become a historical landmark.

•••1857 - A.J. Cross, a city employee, tears down the lighthouse and Fort, excluding the officers` quarters.

•••1871 October 8 - The last portion of Fort Dearborn is destroyed in the great fire of Chicago.

In 1824, at a time when the Fort was not garrisoned, Alexander Wolcott, Indian agent at Fort Dearborn, suggested to J.C. Calhoun, secretary of war, that the land on which the Fort stood - bordered by the lakeshore, Madison Street, State Street, and the main river - be declared a military reservation; the secretary agreed and made the necessary arrangements.

In April 1839, the significant portion of the reservation was released by the secretary of war, J.R. Poinsett, and became the Fort Dearborn Addition to Chicago; a war office agent, Matthew Birchard, surveyed the addition, laying in lots and streets and filed the map with Cook County; all lots were sold except the portion where the lighthouse stood.

The two following letters, later published in the Chicago Tribune on February 2, 1884, one by Dr. Wolcott, the other by George Graham of the U.S. General Land Office:

Fort Dearborn, September 2, 1824.

The Hon. J.C. Calhoun, Secretary of War

The Hon. J.C. Calhoun, Secretary of War

The site of the Fort Dearborn Massacre is claimed to be on the corner of 18th street and Prairie Avenue in modern-day Chicago.

For over a century, the massacre site was marked by a large cottonwood tree. After the tree died, it was replaced by a bronze statue, "Black Partridge Saving Mrs. Helm," commissioned by George Pullman in 1893 at the cost of $30,000, created by the artist Carl Rohl-Smith (1848-1900).

George Pullman wrote:

George Pullman wrote:

Chicago's relief on Michigan Avenue Bridgehouse (renamed the 'DuSable Bridge' in 2010) commemorates the Fort Dearborn Massacre. (built 1918-1920)

On Saturday, August 15, 2009, the Chicago Park District dedicated the site as "Battle of Fort Dearborn Park," in some misguided attempt to be politically correct, somewhat sanitizing history, they renamed the event from "massacre" to "battle" naming it the "Site of Battle of Fort Dearborn."

On Saturday, August 15, 2009, the Chicago Park District dedicated the site as "Battle of Fort Dearborn Park," in some misguided attempt to be politically correct, somewhat sanitizing history, they renamed the event from "massacre" to "battle" naming it the "Site of Battle of Fort Dearborn."

The plaque, somewhat historically suspect, reads:

The plaque, somewhat historically suspect, reads:

[1] "SAVAGE" is a word defined in U.S. dictionaries as a Noun, Verb, Adjective, and Adverb. Definitions include:

The term Red Men is often used in historical books, biographies, letters, and articles written in the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries.

I change this derogatory term to "INDIANS" to keep with the terminology of the time period I'm writing about.

|

| Fort Dearborn in 1850. |

The Chicago Fire of 1857 destroyed nearly all the remaining buildings in the Fort.

By the Civil War (1861-1865), Fort Dearborn's remaining blockhouse and few surviving outbuildings were being used by the Harbor Master of Chicago.

|

| Woodcut from a photo taken in 1855 by Alexander Hesler, from the U. S. Marine Hospital, looking north-west, correctly represents two of the principal buildings of the Fort — the Commandant's Quarters, A (brick, about 25×50 ft.), and the Officers' Quarters, B (wood, about 30×60 ft,), occupying the north-west corner of the enclosure. C is the parade ground (80×200 ft.); D is the Sutler's; E is the north gate. The figure in the foreground is J. D. Graham, U. S. Engineer, in charge of Govt. Works, and residing in the Fort, and to his right, Mr. and Mrs. John H. Kinzie. The vessel in the river on the right is Maria Hillard's brig. The Rush Street Ferry was used crossing the river here and landed on the South-side at a point, indicated in this view, under the west chimney of the Commandant's quarters; the direction of the ferry from this point to the North-side was nearly north-west; width of the channel, 225 feet. |

|

| Fort Dearborn in 1856. An Alexander Hesler photograph. |

|

| Fort Dearborn Blockhouse and Light House in 1857. |

The site of Fort Dearborn is a Chicago Landmark by the Michigan–Wacker Historic District.

|

| These are the brass markers indicating the Fort's footprint. |

FORT DEARBORN; WHEN CHRISTENED.

It has been often stated, that only after the re-building of the Fort (completed in 1817,) it first received the name Fort Dearborn. This was incorrect, for in 1812, the name seems to have been generally known, as the Eastern newspapers mostly referred to the garrison on learning the news of the abandonment of the Fort by the troops, and the immediate treachery of the Indians.

A letter from the War Department admits this, though their records fail to impart anything definite of an earlier date. Yet evidence from other sources has not been wanting, to confirm the statement, that this post was called "Fort Dearborn" in the year it was first finished, in 1804. The fact appeared in the accounts and papers of the elder John Kinzie, who was there that year. Those documents, at the time of the Great Chicago Fire in 1871, were in the library of the Chicago Historical Society. But a living witness is here today, October 30, 1875, who was here when the Fort was built in 1803-04, and she has assured us of the fact above stated; we allude of course to Mrs. Whistler.Excerpt from: Chicago Antiquities; comprising original items and relations, letters, extracts, and notes, about early Chicago. By Henry H. Hurlbut, Member of the Chicago Historical Society, 1881

FORT DEARBORN COMMANDANTS:

•••1803 August 17 to 1810 - Captain Whistler returns in the company of his wife, three children, and 68 military personnel. He designed and built Fort Dearborn, becoming the first commandant; when cold weather arrived late in 1803, the troops were modestly sheltered.

•••1810 to 1812 August 15 - Captain Nathan Heald is named commandant.

•••1810 November to 1811 June - Lieutenant Philip Ostrander serves as acting commandant during Captain Heald's nine-month furlough.

•••1812 August 9 - Captain Heald receives orders from General Hull to evacuate the post and to remove its occupants to Detroit.

•••1812 August 15 - The Fort Dearborn Massacre occurs one and one-half miles south of the Fort as the garrison moves out. Four to five hundred Potawatomi attacked, killing 52 soldiers and civilians. Fifteen Indians are slain in action. Captain Heald survives.

•••1812 August 16 - Indians burn the Fort.

•••1816 July 4 to 1817 May - Captain Hezekiah Bradley, Third Infantry, arrives from Detroit with a garrison of 112 men; he designs and builds the second Fort Dearborn and becomes its first commandant.

•••1817 May to 1820 June - Brevet Major Daniel Baker, Third Infantry, Commandant

•••1820 June to 1821 January - Captain Hezekiah Bradley, Third Infantry, Commandant

•••1821 January to 1821 October - Major Alexander Cummings, Third Infantry, Commandant

•••1821 October to 1823 July - Lieutenant Colonel John McNeil, Third Infantry, Commandant

•••1823 July to 1823 October - Captain John Greene, Third Infantry, Commandant

•••1823 October to 1828 October 3 - Fort Dearborn remains unoccupied and is left in the care of Indian agent, Dr. Alexander Wolcott.

•••1828 October 3 to 1830 December 14 - Brevet Major John Fowle, Fifth Infantry, Commandant

•••1830 December 14 to 1831 May 20 - First Lieutenant David S. Hunter, Fifth Infantry, Commandant

•••1831 May 20 to 1832 June 17 - Fort Dearborn remains unoccupied and is left in the care of Indian agent Thomas J.V. Owen. A portion of the structure serves as a general hospital after July 11, 1831.

•••1831 - The U.S. Congress appropriates $5000 for the construction of a lighthouse which is built within the year near the N.W. corner of the stockade. The lighthouse collapsed soon after completion, and a new, sturdier one was erected in 1832.

•••1832 June 17 to 1833 May 14 - Major William Whistler, Second Infantry, Commandant [son of Captain John Whistler]

•••1833 May 14 to 1833 June 19 - Captain and Brevet Major John Fowle, Fifth Infantry, Commandant

•••1833 June 19 to 1833 October 31 - Major George Bender, Fifth Infantry, Commandant

•••1833 October 31 to 1833 December 18 - Captain DeLafayette Wilcox, Fifth Infantry, Commandant

•••1833 December 18 to 1835 September 16 - Major John Greene, Fifth Infantry, Commandant

•••1835 September 16 to 1836 August 1 - Captain DeLafayette Wilcox, Fifth Infantry, Commandant

•••1836 May 28 - Jean Baptiste Beaubien, a colonel in the Militia of Cook County, purchases land that contains the Fort Dearborn Reservation, including the Fort, for $94.61 from the U.S. Land Office in Chicago and receives a certificate. The U.S. Government later contests the sale.

•••1836 July - Colonel Beaubien's lawyer, Murray McConnell, brings legal action of ejection from the Fort against the commandant, Captain DeLafayette Wilcox.

•••1836 August 1 - Captain and Brevet Major Joseph Plympton, Fifth Infantry, replaces Captain Wilcox as Commandant.

•••1836 December 29 - Troops are permanently withdrawn from Fort Dearborn. Only Ordinance-Sergeant Joseph Adams and Captain Plympton remain responsible for Government property.

•••1837 May - Captain Plympton, last commandant, leaves the Fort; Captain Louis T. Jamison remains until late autumn, detailed on recruiting service.

•••1839 March - U.S. Supreme Court vacates Colonel Beaubien's purchase of Fort Dearborn.

•••1839 June 20 - Fort Dearborn Reservation, divided into blocks and lots by order of the Secretary of War, is sold to multiple private parties for the highest bids; receipts total $106,042.00.

•••1840 December 18 - Colonel Beaubien surrenders his certificate of purchase for Fort Dearborn, and the purchase price of $94.61 is returned to him.

•••1856 - Alexander Hesler photographs the abandoned Fort that has become a historical landmark.

•••1857 - A.J. Cross, a city employee, tears down the lighthouse and Fort, excluding the officers` quarters.

•••1871 October 8 - The last portion of Fort Dearborn is destroyed in the great fire of Chicago.

THE FORT DEARBORN RESERVATION.

In April 1839, the significant portion of the reservation was released by the secretary of war, J.R. Poinsett, and became the Fort Dearborn Addition to Chicago; a war office agent, Matthew Birchard, surveyed the addition, laying in lots and streets and filed the map with Cook County; all lots were sold except the portion where the lighthouse stood.

|

| Fort Dearborn Reservation is listed as belonging to the United States Treasury Department. You can see the Marine Hospital and the Illinois Central Railroad. |

Fort Dearborn, September 2, 1824.

The Hon. J.C. Calhoun, Secretary of War

Sir, I have the honor to suggest to your consideration the propriety of making a reservation of this post and the fraction on which it is situated for use of this agency. It is very convenient for that purpose, as the quarters afford sufficient accommodations for all the persons in the employ of the agency, and the storehouses are safe and commodious places for the provisions and other property that may be in charge of the agent. The buildings and other property, by being in possession of a public officer, will be preserved for public use, should it ever again be necessary to occupy them again with a military force. - As to the size of the fraction, I am not certain, but I think it contains about sixty acres. A considerably greater tract than that is under the fence, but that would be abundantly sufficient for the use of the agency, and contains all the buildings attached to the fort - such as a mill, barn, stable, etc. - which it would be desirable to preserve. I have the honor to be Alexander Wolcott, an Indian Agent.General Land Office, October 21, 1824.

The Hon. J.C. Calhoun, Secretary of War

Sir, In compliance with your request, I have directed that the Fractional Section 10, Township 39 North, Range 14 East, containing 57.50 acres, and within which Fort Dearborn is situated, should be reserved from sale for military purposes. I am, George Graham.

MEMORIALS OF THE FORT DEARBORN MASSACRE.

For over a century, the massacre site was marked by a large cottonwood tree. After the tree died, it was replaced by a bronze statue, "Black Partridge Saving Mrs. Helm," commissioned by George Pullman in 1893 at the cost of $30,000, created by the artist Carl Rohl-Smith (1848-1900).

”An enduring monument, which should serve not only to perpetuate and honor the memory of the brave man and women and innocent children — the pioneer settlers who suffered here — but should also stimulate a desire among us and those who are to come after us to know more of the struggles and sacrifices of those who laid the foundation of the greatness of this city.”The monument, to the dismay of many, was removed in 1931. It was last seen stored in a City of Chicago garage below the overpass near Roosevelt Road and Wells Street.

Chicago's relief on Michigan Avenue Bridgehouse (renamed the 'DuSable Bridge' in 2010) commemorates the Fort Dearborn Massacre. (built 1918-1920)

|

| "Defense Relief" - Fort Dearborn stood almost on this spot. After a heroic defense in eighteen hundred and twelve, the garrison, women, and children were forced to evacuate the Fort. Led forth by Captain Wells, they were brutally massacred by the Indians. They will be cherished as martyrs in our early history. By Henry Hering. 1928 |

Battle of Fort Dearborn - August 15, 1812

From roughly 1620 to 1820 the territory of the Potawatomi extended from what is now Green Bay, Wisconsin, to Detroit, Michigan and included the Chicago area. In 1803, the United States Government built Fort Dearborn at what is today Michigan Avenue and Wacker Drive, as a part of lucrative trading in the area from the British. During the War of 1812, between the United States and Great Britain, some Indian tribes allied with the British to stop the westward expansion of the United States and to regain lost Indian lands. On August 15, 1812, more than 50 US soldiers and 41 civilians, including 9 women and 18 children were ordered to evacuate Fort Dearborn. This group, almost the entire population of U.S. citizens in the Chicago area, marched south from Fort Dearborn, along Lake Michigan until they reached this approximate site, where they were attacked by about 500 Potawatomi. In the battle and aftermath, more than 60 of the evacuees and 15 native Americans were killed. The dead included Army Captain William Wells, who has come from Fort Wayne, with Miami Indians to assist in the evacuation, and Naunongee, Chief of the Village of Potawatomi, Ojibwe and Ottawa Indians known as the Three Fires Confederacy. In the 1830s the Potawatomi of Illinois were forcibly removed to lands west of Mississippi. Potawatomi Indian Nations continue to thrive in Michigan, Indiana, Wisconsin, Kansas, Oklahoma, and Canada, and more than 36,000 American Indians, from a variety of tribes, live in Chicago today.”Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

[1] "SAVAGE" is a word defined in U.S. dictionaries as a Noun, Verb, Adjective, and Adverb. Definitions include:

- a person belonging to a primitive society

- malicious, lacking complex or advanced culture

- a brutal person

- a rude, boorish, or unmannerly person

- to attack or treat brutally

- lacking the restraints normal to civilized human beings

The term Red Men is often used in historical books, biographies, letters, and articles written in the 18th, 19th, and early 20th centuries.

I change this derogatory term to "INDIANS" to keep with the terminology of the time period I'm writing about.

"HALF-BREED" is a disrespectful term used to refer to the offspring of parents of different racial origins, especially the offspring of an American Indian and a white person of European descent.