In historical writing and analysis, PRESENTISM introduces present-day ideas and perspectives into depictions or interpretations of the past. Presentism is a form of cultural bias that creates a distorted understanding of the subject matter. Reading modern notions of morality into the past is committing the error of presentism. Historical accounts are written by people and can be slanted, so I try my hardest to present fact-based and well-researched articles.

Facts don't require one's approval or acceptance.

I present [PG-13] articles without regard to race, color, political party, or religious beliefs, including Atheism, national origin, citizenship status, gender, LGBTQ+ status, disability, military status, or educational level. What I present are facts — NOT Alternative Facts — about the subject. You won't find articles or readers' comments that spread rumors, lies, hateful statements, and people instigating arguments or fights.

FOR HISTORICAL CLARITY

When I write about the INDIGENOUS PEOPLE, I follow this historical terminology:

- The use of old commonly used terms, disrespectful today, i.e., REDMAN or REDMEN, SAVAGES, and HALF-BREED are explained in this article.

Writing about AFRICAN-AMERICAN history, I follow these race terms:

- "NEGRO" was the term used until the mid-1960s.

- "BLACK" started being used in the mid-1960s.

- "AFRICAN-AMERICAN" [Afro-American] began usage in the late 1980s.

— PLEASE PRACTICE HISTORICISM —

THE INTERPRETATION OF THE PAST IN ITS OWN CONTEXT.

THE OLD TOWN TRIANGLE HISTORY

First settled by German immigrants in 1850, the area was known as the "Cabbage Patch" from the German immigrants who grew cabbages, potatoes, and celery on the marshy land. The area was called "North Town" (not Nortown) as it straddled North Avenue, then the northern boundary of Chicago proper.On October 14, 1948, about 25 neighborhood residents met to discuss improving what was referred to as Old Town (the attribution of which is generally credited to Charles Collins of the Chicago Tribune in 1944). At that time, the "founders" referred to the area as "The Clark, Ogden, North Triangle," later shortened to "The Triangle" until September 20, 1951, when members voted to officially change the name to the "Old Town Triangle Association," (OTTA) which was initially sponsored by the Chicago city agency, the North Side Planning Council.

During World War II, the triangular area bordered North Avenue, Clark Street, and Ogden Avenue, which ran up to Lincoln Park until the 1960s. It was designated a "neighborhood defense unit" by the Chicago Civil Defense Corps.

The Great Depression was hard on Old Town, and it fell into a state of . . . well, depression. Disheveled and dirty, the once-lovely neighborhood was in jeopardy of losing its unique identity. In the 1940s, the residents rose to reclaim and make the neighborhood shine again. They banded together and formed the Old Town Triangle Association, a super-active community organization headquartered in the Triangle today.

One of the Association's first initiatives was the establishment of a small Art Fair. This event catalyzed Old Town's revival, attracting visitors to discover the neighborhood's hidden gems and reawaken its dormant spirit. With each passing year, the Art Fair grew in size and popularity, transforming Old Town into a vibrant hub of creativity and cultural exchange.

Helen Guilbert and Sara Jane Wells were two movers and shakers regarding trees in the Triangle, planting flowering "Hopa" crabapple trees in 1959. They watered the trees with the help of area residents loaning their garden hoses to water the trees by their houses for the months it took them to stabilize and then let Mother Nature take over.

When Bob Switzer passed away, he endowed the Old Town Triangle Association with funds to improve the parkways in the late 1970s.

THE MENOMONEE BOYS CLUB

The Menomonee Boys Club was founded in 1946 by a group of concerned Old Town neighbors to "provide wholesome recreation as a means of keeping children off the streets." Menomonee funding has always been tied closely to the neighborhood.

In 1950, the Club's director, Joe Vitale, discovered a two-lane bowling alley on Willow, and The Club could buy it for $13,000. Its founding members scraped a down payment and spent the next four years raising the remaining money for the Menomonee Clubhouse. When it was finally paid for, a celebration was held – a mortgage-burning party!

This building is called the Willow Clubhouse, opened in 1950, and is the oldest of four Menomonee Club buildings.

With the help of the North Side Boys Club, the group rented an Old Town storefront and began offering ping pong, shuffleboard, boxing, baseball, woodworking, and choral singing. Membership was 50 cents, and more than 100 children joined during the first few weeks. It started out being a boys' Club, with girls allowed in once per week. That didn't last long. Soon, girls regularly came, and The Menomonee Club for Boys and Girls was born. Kids gathered to take lessons, play checkers, and just hang out.In 1950, the Club's director, Joe Vitale, discovered a two-lane bowling alley on Willow, and The Club could buy it for $13,000. Its founding members scraped a down payment and spent the next four years raising the remaining money for the Menomonee Clubhouse. When it was finally paid for, a celebration was held – a mortgage-burning party!

THE OLD TOWN ART FAIR

The Crilly Court Apartments held a Jamboree (block party) that predated the Old Town Art Fair to raise money for a playground. The event was so successful that the Crilly residents expanded its mission to include The Menomonee Club and other neighborhood activities. Folklore says the Jamboree inspired the Art Fair.

The Old Town Triangle Association decided to hold an art fair they named "Old Town Holiday" in June 1950 to raise funds for the Menomonee Club. Shortly after, the name of the art fair was changed to the Old Town Art Fair, which evolved into a nationally known event.

The Old Town Triangle Association decided to hold an art fair they named "Old Town Holiday" in June 1950 to raise funds for the Menomonee Club. Shortly after, the name of the art fair was changed to the Old Town Art Fair, which evolved into a nationally known event.

|

| Old Town, Chicago, Art Fair, 1950. |

THE HISTORY OF OLD TOWN

Wells Street, before the 1909 Chicago street renaming and renumbering, was 5th Avenue. Soon, Wells Street, which runs vertically through the neighborhood, became the place to see and be seen, shop, eat, and be entertained.

Old Town was an old town, a sleepy neighborhood on Chicago's North Side. The Old Town School of Folk Music opened in December 1957 with its first home in the Old Town neighborhood of the Lincoln Park Community at 333 West North Avenue, sparking a cultural revolution. The school attracted musicians and artists from all over the country, and soon, Old Town was transformed into a vibrant center for counterculture.

sidebar

sidebar

The School purchased and moved into a 13,000-square-foot building at 909 West Armitage Avenue in the Ranch Triangle neighborhood in the Lincoln Park Community. The School was able to renovate the Armitage Avenue facility by 1987, a renovation that contributed to a surge in the School's popularity. The School won the prestigious Beatrice Foundation Award for Excellence that same year.

The school attracted musicians and artists from all over the country, and soon, Old Town was transformed into a vibrant center for counterculture.

North Wells Street became the heart of Old Town. The street was lined with shops, cafes, music venues, and museums enjoyed by residents and tourists alike. It was a place where people could come to people watch, express themselves freely, be entertained, and experience new things.

Old Town Triangle (North of North Avenue) is a neighborhood in the Lincoln Park community, which is one of the 77 communities of Chicago.

Old Town (South of North Avenue) is a neighborhood in the Near North Side community, which is one of the 77 communities of Chicago.

sidebar

St. Michael's Catholic Church at 234 Hurl-but Street (1633 North Cleveland Avenue today) stands as a testament to resilience. Built in 1869, the church was one of only six structures to withstand the devastating Great Chicago Fire of 1871. While the flames engulfed the surrounding neighborhood, St. Michael's, constructed of sturdy Chicago brick, remained standing, albeit heavily damaged. The fire's intense heat had warped the church's steel beams and shattered its windows. The interior was reduced to rubble, and the roof was in tatters. Yet, the brick walls held firm, providing a beacon of hope amidst the ruins.With remarkable determination, the congregation rallied to rebuild their beloved church. The fire had laid waste to the neighborhood, destroying nearly every building (Two houses at 632 and 650 Hurl-but Street {2323 and 2339 North Cleveland Avenue today} claimed to be survivors. I'm having difficulty verifying this). The once vibrant community was reduced to a smoldering landscape.Within two years, St. Michael's had risen from the ashes, its exterior restored and its interior adorned with new furnishings. The church's bell, which had miraculously survived the fire, once again pealed its call to prayer, signaling a new chapter for St. Michael's and the Old Town neighborhood.

The residents changed the direction of streets (St. Paul and Eugenie) to one way going east to spare themselves the horrendously large volume of auto traffic on Wells Street. In the 1960s, there was so much Friday and Saturday night traffic that it could take 2 hours to drive both ways from North Avenue to Division Street.

Wells Street became Old Town's main street sometime in the early 1960s. Rumor has it that the Old Town School of Folk Music, founded in 1957, was the catalyst for the retail development of Wells Street as musicians flooded into the area to eat, drink, and enjoy the flourishing entertainment establishments. Retailers quickly followed.

Helen Guilbert ran a short-lived newspaper called "The Old Town News" in 1957.

In an age when people were fleeing the city for the suburbs, and then urban renewal was leveling nearby areas, local small business owners dug in, and Old Town became a medley of bohemian artists, trendy shops, flashy tourist spots, bars and taverns, museums, and lots of restaurants.

sidebar

Old Town is a pretty small area, even using Google’s generous borders, measuring one mile north to south and just shy of a mile east to west. Run the perimeter, and you’ll have a 5k under your belt.

sidebar

The Second City Theatre opened on December 16, 1959, at 1842 N. Wells, the former site of Wong Cleaners & Dyers. In the 1960s, The Second City expanded, becoming a hangout for celebrities like Anthony Quinn and Hugh Hefner. The Second City makes its first (but not last move), swapping addresses with their new, larger theater next door.

In 1967, the Second City moved south to 1616 N. Wells Street. Today, The Second City (Theatre) is in Pipers Alley Mall, 230 West North Avenue, Chicago, Illinois.

Old Town sales peaked in 1965. In the late 1960s, Old Town became Chicago's hippie haven. Old Town's heyday was in the 1960s and 1970s. The neighborhood has never lost its bohemian spirit.

All Time Businesses in Old Town:

PLEASE COMMENT BELOW IF YOU CAN ADD TO THIS LIST

- Barbara's Bookstore

- Beans

- Bizzare Bazaar (Hippy & Head Shops)

- A Marijuana Paraphernalia Vendor (1960s-70s)

- A Silver Jewelry Vendor

- Indoor Bumper Car Ride

- T-Shirt Shop (Tie Dye & Heat Transferred Decals)

- Bootleg Records

- Caravan

- Climax Art Gallery

- Crate and Barrel

- Dabstract ($1 Spin Painting)

- Dave Menza - Old Town Photography

- Davis-Congress Men's Wear

- Fly by Night Antiques

- Footworks, 1700 N Wells

- Head Quarters (Head Shop)

- Horse of a Different Color

- Horsefeathers

- Horse of a Different Color (Clothing)

- House of Glunz (liquor sales since 1888)

- John Brown's Sandal Shop

- Kandy Barrel

- Leather Fetish (Clothing)

- Madge Women's Clothing

- Maiden Lane [Indoor] Shopping Center (1525 North Wells Street)

- Granny's Good Fox Toy Store

- The Smugglers Gifts (Head Shop)

- The Tye Shop

- The Wiggery

- Old Town Aquarium

- Old Town Gate (Antiques)

- Parlor Jewelry

- That Paper Place

- The Apartment Store

- The Emporium

- The Fig Leaf

- The Fudge Shop

- The Man at Ease

- The Old Town Auction House

- The Old Town Shop

- The Old Treasure Chest

- The Oriental Gift Shop

- The Paper Dress Store

- The Peace Pipe (Head Shop)

- The Scratching Post

- The Town Shop

- The Toy Gallery

- The What Not Shop

- The Wick-ed Shoppe (Candles)

- Toptown Clothing

- Up Down Cigar Shop

- Wecord Woom

- Zanies Comedy Night Club, 1548 N Wells

SHOPPING CENTERS ON WELLS STREET

MAIDEN LANE at 1525 North Wells Street, a shopping center that fits almost none of the conventional ideas of what a shopping center should look like, opened in May of 1966 with space for 20 shops. Maiden Lane was once a garage owned by Henry Susk of Susk Pontiac.Henry Susk found the garage was surrounded by gift shops, antique stores, restaurants, and bistros that have changed the character of North Wells Street. He decided the building could be remodeled to create the atmosphere of London's Old Maiden Lane shopping area.

The "Lane" ran through the center of the building, lined with small shops reminiscent of London, and old English gaslights add to the illusion. Near the rear of the building, the lane widens into a square with a fountain.

Frank C. Wells, Senior Vice President of L.J. Sheridan & Company, Maiden Lane's leasing agent, said this may be one of the smallest shopping centers the firm has ever assisted in developing and leasing. It is also one of the most interesting. Wells pointed out that Maiden Lane follows the latest concepts of shopping center design, including a heated covered mall, outstanding shopper circulation, and distinctive architecture.

Frank C. Wells, Senior Vice President of L.J. Sheridan & Company, Maiden Lane's leasing agent, said this may be one of the smallest shopping centers the firm has ever assisted in developing and leasing. It is also one of the most interesting. Wells pointed out that Maiden Lane follows the latest concepts of shopping center design, including a heated covered mall, outstanding shopper circulation, and distinctive architecture.

MAIDEN LANE SHOPPING CENTER. THERE WERE MORE THAN SIX SHOPS INSIDE:

- Granny Goodfox Toy Boutique

- One Octave Lower (Record Store)

- The Smugglers Gift Shop

- The Tye Shop

- The Wiggery

- Watch the Birdie (Souvenir Photo Studio)

|

| A giant Tiffany lamp hung outside the entrance to the maze of unusual retail shops. |

Pipers Alley, 1608 North Wells Street, was opened in November of 1965 by Rudolph Schwartz and Jack Solomon, owners of the five buildings making up the 15 shops that once made up Piper's Bakery and stables.

Shoppers, diners, and the curious walked up and down an original turn-of-the-century alley paved with Chicago Street Paver Bricks and lined with time-period street lamps.

WITHIN PIPER'S ALLEY: Businesses & Restaurants (throughout time)

PLEASE COMMENT BELOW IF YOU CAN ADD TO THIS LIST

- Aardvark Cinematheque (Movie Theatre)

- Arts International Gallery

- Baskin-Robbins Ice Cream

- Bijou Theater, 1349 N Wells (77-seat art films house)

- Bustopher Jones Women's Boutique

- Caravan

- Charlie's General Store

- Design India (Furniture and Imported Items)

- Flypped Disc Record Shop

- Grin N Bare It

- In Sanity (Party Goods Store)

- Jack B. Nimble Candle Shop

- John Brown's Leather Works

- La Piazza Restaurant

- Off the Hook (Decorator Items)

- One Octave Lower

- Peace Pipe (Smoking Paraphernalia)

- Personal Posters (Instant Immortality - photo to poster in 15 minutes)

- Poor Richards

- Second Hand Rose

- The Sweet Tooth

- That Steak Joynt Restaurant [Entrance on Wells Street ] (Claimed Haunted as customers and staff reported.)

- That Hair Shoppe

- The Bratskellar Restaurant

- The Caravan (Handcrafts Store)

- The Flypped Disc (Record Store)

- The Glass Unicorne

- The Hungry Eye

- The Jewelry Shop

- The Male M1 Men's Shop

- The Sweet Tooth (Old Fashioned Candy)

- Tiffany Light Store

- Two Brothers

- Volume 1 Bookstore

- Willoughby's Restaurant

- Ye Olde Farm House Restaurant [Entrance on Wells Street ]

|

| A 1960s Advertisement |

|

| Note the original "Chicago Street Paver Bricks" in Piper's Alley. |

|

| Charlies General Store |

|

| La Piazza in Pipers Alley, 1967 |

Now Leaving Pipers Alley

Entertainment & Pubs (all-time) in Old Town:

PLEASE COMMENT BELOW IF YOU CAN ADD TO THIS LIST

- Big John's Blues Club, 1638 North Wells Street

- Bikini A Go-Go (Adult Entertainment)

- Encore Theater

- House of Horror

- Jamie's (Adult Entertainment)

- John Barleycorn Bar & Eatery

- Judy's Juniors- 'Teenage Halabalu'

- Le Bison Discotheque

- Like Young (Teen) Nightclub

- Marge's Still (since 1955), in Old Town Triangle (A Pub since 1885)

- Midas Touch (Adult Entertainment)

- Moody's Pub

- Mother Blues (Folk-Rock)

- My Sister's Place (For the Younger Set)

- Philrowe Club (Adult Entertainment)

- Quiet Knight

- Ripley's Believe It or Not! (Oddity Museum)

- Second City Theater

- Tap Root Pub

- The Crystal Pistol (Adult Entertainment)

- The Earl of Old Town Cafe & Pub

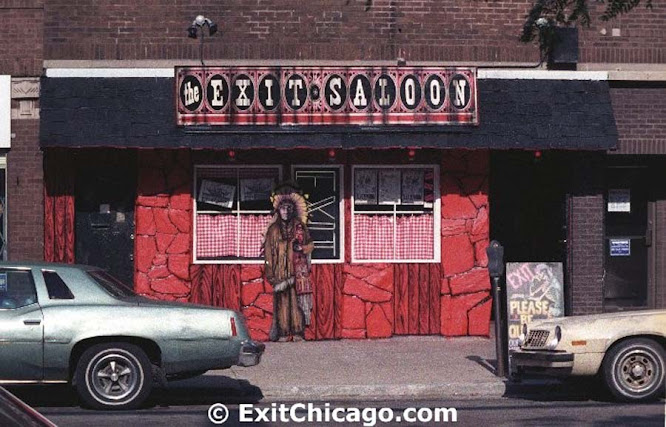

- The Exit Saloon

- The Old Town Ale House, 219 W North Avenue

- The Old Town School of Folk Music

- The Outhaus (Adult Entertainment)

- The Plugged Nickle (Jazz)

- The Purple Cow

- The Royal London Wax Museum

- The Sewer Discotheque

- The Snug (Piano Bar decorated like a medieval torture chamber)

- Window A Go-Go (Adult Entertainment)

Restaurants & Foods (all-time) in Old Town:

PLEASE COMMENT BELOW IF YOU CAN ADD TO THIS LIST

- Antonio's Steak House

- Beef & Bourbon Restaurant

- Bistró Margot

- Cafe Azteca

- Chances R Restaurant

- China Doll Restaurant

- Cow Palace Restaurant

- Dinottos

- Franksville Hot Dogs (Maden Lane)

- Grotto Pizza

- La Piazza Restaurant (Pipers Alley)

- La Strada Restaurant (Continental)

- Little Pleasures Cafe & Ice Cream Parlor

- Lum's Restaurant (SW corner North & Wells)

- My Л (Pi) Pizza Restaurant (1119 N Wells) 1964-1972

- O'Briens Restaurant, 1528 N Wells

- Old Farm House Restaurant (Pipers Alley)

- Old Fashioned Fudge

- Old Town Ale House

- Old Town's Boss Coffee House

- Old Town Pump Restaurant/Pub

- Old Town Rib Shack

- Orsos Restaurant

- Piper's Bakery (Pipers Alley)

- Paul Bunyan Restaurant (Family)

- "Hot Biscuit Slim's" Paul Bunyan Bakery

- That Steak Joynt (Pipers Alley) [claimed to be haunted as customers and staff members reported bizarre supernatural experiences.]

- The Bowery

- The Bowl and Roll

- The Cave Restaurant

- The Donut Whole

- The Fireplace Inn (Upscale)

- The Fudge Pot

- The Golden Dragon Cantonese Restaurant

- The Pickle Barrel Restaurant (Jewish Delicatessen)

- The Pup Room (Red Hots & Hamburgers)

- Three Brother's Pizza

- Stagecoach Restaurant (SE corner North & Wells)

- Soup's On Restaurant

- Tea for Two

- Topo Gigio

- Topper's Beef & Bourbon, 1560 N Wells

- Twin Anchors (in Old Town Triangle)

- Uno's Pizza (Deep-Dish)

- Ye Olde Farm House Restaurant (Family)

The Cave Restaurant, served Japanese food at 1339 North Wells, then the Bowl and Roll, opened at 1339 North Wells. In November 1974, the Chicago Tribune raved about the Bowl and Roll's delicious soup and the choice of three sandwiches.

|

| La Strada Restaurant Entrance at 1531 N. Wells Street, 1965 |

|

| La Strada, 1531 N. Wells Street, Old Town, Chicago, 1965 postcard. A Continental Restaurant with an authentic European atmosphere provided by the owner, Buona Fortuna. |

|

| La Strada, 1531 N. Wells Street, Old Town, Chicago, 1965 postcard. A Continental Restaurant with an authentic European atmosphere provided by the owner, Buona Fortuna. |

Besides the restaurants in Piper's Alley, other Old Town restaurant choices included the Chances R Restaurants, famous for burgers and for allowing you to throw peanut shells on the floor. The restaurant's name reflected the uncertainty of this first location in Old Town. "Chances are we could go broke," the owners reportedly said among themselves.

|

| Chances R, c.1965 |

|

| Chances R |

|

| Chances R Interior |

|

| The Pickle Barrel Restaurant, 1423 North Well, Old Town, 1971. |

There was the Paul Bunyan restaurant with "Hot Biscuit Slim's" Bakery (home of the 12" cookie), and the Buzz Saw Bar with drinks named the Big Onion, the Blue Ox, Axman's Revenge, Tall Timber, the Log Pond, and the Ax Handle. Paul Bunyan's motto was, "We have an oversized desire to serve the best food at the most sensible prices to the greatest number of people."

Restaurants included the Golden Dragon Cantonese Restaurant, the Stage Coach Restaurant, and the Beef & Bourbon Restaurant, and at least we forget Lum's Restaurant, which was on the southwest corner of North Avenue and Wells Street.

It was home to the famed Second City Theater, Uno's, Bizzare Bazaar (Head Shop), The Fudge Pot, the Town Shop, Madge women's clothing store, Parlor Jewelry, a penny candy shop, the Wick-ed Shoppe (a candle store), the House of Lewis, and The Man at Ease (a hip men's clothing store).

It was home to the famed Second City Theater, Uno's, Bizzare Bazaar (Head Shop), The Fudge Pot, the Town Shop, Madge women's clothing store, Parlor Jewelry, a penny candy shop, the Wick-ed Shoppe (a candle store), the House of Lewis, and The Man at Ease (a hip men's clothing store).

sidebar

Snatch and grab of merchandise was heavy in the 1960s. "And shop-lifting! I have a rate of loss that would curl your hair,” said a merchant.

|

| Adult Entertainment |

|

| View from 1500 North Wells Street in Old Town neighborhood; Chicago, Illinois, July 3, 1970. The west side of the street includes the Fireplace Inn, the 'Wecord Woom,' Crystal Pistol, and the Ripley's Believe It or Not! Museum. |

|

| The Fig Leaf and Paper Dress Store. |

That Paper Place was owned by Cherly Siegel, the wife of Bill Siegel, who was part-owner of Bizarre Bazaar. They sold giant paper flowers, decorations, cards, paper lanterns, shades, and light fixtures.

The Great Old Town Movie Poster & Comic Book Company was located at 1444 North Wells Street.

The House of Horror was a spooky, creepy place for kids to see. I had nightmares.

|

| House of Horrors was close to Lum's, across the street from the Emporium. |

The Royal London Wax Museum (figures by Josephine Tussaud) was at 1419 N. Wells Street. It included lifelike figures of Chicagoans Ernie Banks, Hugh Hefner, Al Capone, St. Valentine's Day Massacre, and figures from the Civil War. The Chamber of Horrors featured replicas of Dracula, the Wolf Man, and Frankenstein, while the fantasy room contained Pinocchio, Cinderella, Rip Van Winkle, and Alice in Wonderland. It closed in 1991.

|

| This photo is not from the Chicago Ripley's Believe it or Not! |

THE MUSIC SCENE

The Earl of Old Town Cafe & Pub at 1615 N. Wells Street was the fabled Club that epitomized the Chicago folk scene and honed such home-grown talent as Steve Goodman, John Prine, and Bonnie Koloc opened in 1962. |

| Earl J.J. Pionke, 1982 |

Chicago's famed Old Town neighborhood had become the epicenter of Chicago's emerging music scene, and Earl knew there was an opportunity to join the movement and make something special. When Pionke opened "The Earl of Old Town" in 1962, he was confident he could get people in the door. He didn't know how yet.

Earl, a colorful and boisterous man, had an infectious personality that helped to build his club's reputation. As longtime Chicago folk-music mainstay Eddie Holstein recalled during Earl's 80th Birthday Celebration, "You don't meet Earl Pionke, you hear him coming." After inviting a few local folk singers to play at the Club, the unexpected success of their performances set Pionke and The Earl of Old Town to showcase the emerging talent and their songs of the times.

Once the spark was lit, it didn't take long before The Earl of Old Town quickly became the hottest Club in the city for emerging folk music. Famed Chicago singers and songwriters, including John Prine, Bonnie Koloc, Jim Post, Steve Goodman, Fred & Eddie Holstein, and many others, all started playing to the warm audiences and bare brick walls of The Earl. For Eddie Holstein, The Earl was the perfect venue for new emerging artists. The Earl of Old Town featured live music nightly, and the crowds piled in consistently. It was a welcoming place. The Earl was refined enough to catch your eye while holding enough charm to make you feel at home. The room's intimacy created an unmistakable and vital sense of presence for the audience and the performers.

"It was a listening room," says Chicago folk veteran Chris Farrell, "you came to hear the music." The music at The Earl thrived for years, and the relationship between Earl and his performers became atypical. They were more family than hired talent. He is more a fan than a benefactor. As quoted in the liner notes of 1970's "Gathering at the Earl of Old Town," Pionke insists, "They're my kids, my pals, I love 'em.'"

The Earl of Old Town closed its doors in 1982. Earl J.J. Pionke died Friday, April 26, 2013, at 80 years old.

sidebar

The Treasure Island Grocery Store (1963-2018) at 1639 North Wells Street, in Chicago's Old Town Triangle, was a beloved neighborhood institution for 54 years. The store was known for its imported foods. They sold high-quality produce, meats, cheeses, and wines and employed friendly and knowledgeable staff. Chef Julia Child once referred to Treasure Island as "America's most European supermarket." The Wells Street store sold for almost $15 million in 2019.

Old Town was a mecca for the music scene. The Old Town School of Folk Music, Mother Blues, the Purple Cow, the Crystal Pistol, Quiet Knight, and the Plugged Nickel were trendy music venues.

Not many people remember The Outhaus at 1311 North Wells Street, which closed in 1968.

Old Town also catered to the under-21 crowds with dance clubs: Judy's Juniors, Like Young, and My Sister's Place.

|

| Lincoln Park Pirates |

The Rising Moon Club at 1305 North Wells Street featured the house band, The New Wine Singers (folk/traditional jazz). Arson destroyed the building in November 1962. Later, Lorraine Blue opened Mother Blues on that site, and the New Wine Singers played as a house band.

The popularity of Chicago's Old Town has waxed and waned over time. This is the time-cycle of the most noticeable change.

HIP—Early 1900s into the 1920s:Resurgence in the 1940s until the mid-1960s, particularly associated with jazz culture and the Beat Generation. Old Town prospered from the working class German immigrant families and blossomed into . . . well, you decide.COOL—1930s thru 1960s:One of the most enduring slang terms. The area becomes a haven for artists, bohemians, and the counterculture movement. The Old Town Art Fair is established, and folk music experiences a revival with venues like the Earl of Old Town and the Old Town School of Folk Music.FAB; [fabulous]—Late 1950s to early 1980s:Old Town gained popularity due to its association with the hippie counterculture and the British pop culture and bands. Wells Street attracts a mix of young professionals, hippies, and teens. The Second City comedy theater thrives. This era sees a surge in popularity and some tensions due to gentrification, weekend crowds, and snatch-and-grab thefts. Teenagers were not forgotten. Clothing Stores, Accessories, Shoes, and plenty of cool stuff you just have to have!

The 1980s— Continued popularity brought gentrification:The neighborhood became less bohemian and more upscale as redevelopment occurred. While some artistic characters are lost, Old Town remains a desirable place to live and visit, with its historic architecture and many shops, upscale boutiques, restaurants and home decor stores.

The Piper's Alley Fire on March 1, 1971.

Fire at the Second City Comedy Club, August 26, 2015.

On Wednesday, August 26, a fire ignited inside a grease chute above the kitchen in Adobo Grill at 1610 N Wells Street. The fire spread to the building housing The Second City, a comedy club and school of improvisation, destroying offices and memorabilia from alumni. Months after the accident, the community was still cleaning up the mess.

Firemen said all the shops on the first floor suffered smoke and water damage. The buildings were estimated to be worth $1½ to $2 million.

On top of repairing fire damage, Second City is undergoing construction as part of an expansion. Building onto what used to be the Aardvark Cinematheque movie theatre in Piper's Alley, they have gutted all that and put in new stages. The expansion of Second City was massive.

On top of repairing fire damage, Second City is undergoing construction as part of an expansion. Building onto what used to be the Aardvark Cinematheque movie theatre in Piper's Alley, they have gutted all that and put in new stages. The expansion of Second City was massive.

A comprehensive list of the 160 businesses and restaurants listed in this article is arranged alphabetically. Comment below if you can add to this list.

- A Headshop & Paraphernalia Vendor (in Bizzare Bazaar 1960s-70s)

- A Silver Jewelry Vendor (in Bizzare Bazaar)

- Aardvark Cinematheque (Movie Theatre in Pipers Alley)

- Antonio's Steak House

- Arts International Gallery

- Barbara's Bookstore

- Baskin-Robbins Ice Cream

- Beans

- Beef & Bourbon Restaurant

- Big John's Blues Club, 1638 North Wells Street

- Bijou Theater, 1349 N Wells (77-seat art films house)

- Bikini A Go-Go (Adult Entertainment)

- Bistró Margot

- Bizzare Bazaar (Hippy & Head Shops)

- Bootleg Records

- Bustopher Jones Women's Boutique

- Cafe Azteca

- Caravan

- Caravan

- Chances R Restaurant

- Charlie's General Store

- China Doll Restaurant

- Climax Art Gallery

- Cow Palace Restaurant

- Crate and Barrel

- Dabstract ($1 Spin Painting)

- Dave Menza - Old Town Photography

- Davis-Congress Men's Wear

- Design India (Furniture and Imported Items)

- Dinottos

- Encore Theater

- Fly by Night Antiques

- Flypped Disc Record Shop

- Footworks, 1700 N Wells

- Franksville Hot Dogs (Maden Lane)

- Granny Goodfox Toy Boutique

- Granny's Good Fox Toy Store

- Grin N Bare It

- Grotto Pizza

- Head Quarters (Head Shop)

- Horse of a Different Color (Clothing)

- Horsefeathers

- "Hot Biscuit Slim's" Paul Bunyan Bakery

- House of Glunz (liquor sales since 1888)

- House of Horror

- In Sanity (Party Goods Store)

- Indoor Bumper Car Ride (Pipers Alley)

- Jack B. Nimble Candle Shop

- Jamie's (Adult Entertainment)

- John Barleycorn Bar & Eatery

- John Brown's Leather Works & Sandal Shop

- Judy's Juniors- 'Teenage Halabalu'

- Kandy Barrel

- La Piazza Restaurant (Pipers Alley)

- La Strada Restaurant (Continental)

- Le Bison Discotheque

- Leather Fetish (Clothing)

- Like Young (Teen) Nightclub

- Little Pleasures Cafe & Ice Cream Parlor

- Lum's Restaurant (SW corner North & Wells)

- Madge Women's Clothing

- Maiden Lane [Indoor] Shopping Center (1525 North Wells Street)

- Marge's Still (since 1955), in Old Town Triangle (A Pub since 1885)

- Midas Touch (Adult Entertainment)

- Moody's Pub

- Mother Blues (Folk-Rock)

- My Sister's Place (For the Younger Set)

- My Л (Pi) Pizza Restaurant (1119 N Wells) 1964-1972

- O'Briens Restaurant, 1528 N Wells

- Off the Hook (Decorator Items)

- Old Farm House Restaurant (Pipers Alley)

- Old Fashioned Fudge

- Old Town Ale House

- Old Town Aquarium

- Old Town Gate (Antiques)

- Old Town Pump Restaurant/Pub

- Old Town Rib Shack

- Old Town's Boss Coffee House

- One Octave Lower (Record Store)

- Orsos Restaurant

- Parlor Jewelry

- Paul Bunyan Restaurant (Family)

- Peace Pipe (Smoking Paraphernalia)

- Personal Posters (Instant Immortality - photo to poster in 15 minutes)

- Philrowe Club (Adult Entertainment)

- Piper's Bakery (Pipers Alley)

- Poor Richards

- Quiet Knight

- Ripley's Believe It or Not! (Oddity Museum)

- Second City Theater

- Second Hand Rose

- Soup's On Restaurant

- Stagecoach Restaurant (SE corner North & Wells)

- T-Shirt Shop (Tie Dye & Heat Transferred Decals)

- Tap Root Pub

- Tea for Two

- That Hair Shoppe

- That Steak Joynt (Pipers Alley) [Entrance on Wells Street ] (Haunted as customers and staff reported.)

- The Apartment Store

- The Bowery

- The Bowl and Roll

- The Bratskellar Restaurant

- The Caravan (Handcrafts Store)

- The Cave Restaurant

- The Crystal Pistol (Adult Entertainment)

- The Donut Whole

- The Earl of Old Town Cafe & Pub

- The Emporium

- The Exit Saloon

- The Fig Leaf

- The Fireplace Inn (Upscale)

- The Flypped Disc (Record Store)

- The Fudge Pot

- The Glass Unicorne

- The Golden Dragon Cantonese Restaurant

- The Hungry Eye

- The Jewelry Shop

- The Male M1 Men's Shop

- The Man at Ease

- The Old Town Ale House, 219 W North Avenue

- The Old Town Auction House

- The Old Town School of Folk Music

- The Old Town Shop

- The Old Treasure Chest

- The Oriental Gift Shop

- The Outhaus (Adult Entertainment)

- The Paper Dress Store

- The Peace Pipe (Head Shop)

- The Pickle Barrel Restaurant (Jewish Delicatessen)

- The Plugged Nickle (Jazz)

- The Pup Room (Red Hots & Hamburgers)

- The Purple Cow

- The Royal London Wax Museum

- The Scratching Post

- The Sewer Discotheque

- The Smugglers Gifts (Head Shop)

- The Snug: A Medieval Torture Chamber Piano Bar

- The Sweet Tooth (Old Fashioned Candy)

- The Town Shop

- The Toy Gallery

- The Tye Shop

- The What Not Shop

- The Wick-ed Shoppe (Candles)

- The Wiggery

- Three Brother's Pizza

- Tiffany Light Store

- Topo Gigio

- Topper's Beef & Bourbon, 1560 N Wells

- Toptown Clothing

- Twin Anchors (in Old Town Triangle)

- Two Brothers

- Uno's Pizza (Deep-Dish)

- Up Down Cigar Shop

- Volume 1 Bookstore

- Watch the Birdie (Souvenir Photo Studio)

- Wecord Woom

- Willoughby's Restaurant

- Window A Go-Go (Adult Entertainment)

- Ye Olde Farm House Restaurant [Entrance on Wells Street ]

- Zanies Comedy Night Club, 1548 N Wells

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Thank you, David Pfendler, Archivist for the Old Town Triangle Association, for the early history of the Old Town Triangle area.