There are references to the game of Pinners beginning around 1949 or earlier.

The batter would throw a rubber or tennis ball at the edge of the step or angled wall brick, and the fielder(s) would try to catch the ball as it bounces back.

|

| The Preferred Pinners Ball. A Spalding "Pinkie" |

The scoring rules are similar to baseball, but with runs being virtually determined by where the ball lands. A single, double, triple or home run would be predetermined landmarks (i.e. sidewalk, trees, cars, street, curb/sidewalk lines) from the batting area. A catch is an out, and a one-handed catch could be used for a "rushie."

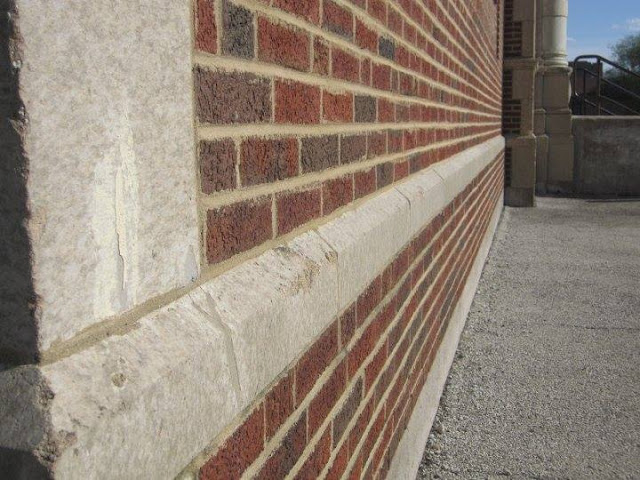

As with most neighborhood games, rules varied by the groups playing, and house rules would be determined at the start of the game, including the base locations. The game utilizes traditional Chicago neighborhood row house architecture (Chicago bungalows), with most houses having a front stoop or stairs that lead from the front door to the sidewalk that can be used. Many of the schools built in Chicago also have a "perfect" angled section of brick which can be used for the game, and often neighborhood kids would paint a box with an X marking the angled sections.

|

| Chicago Public School exterior wall with a ledge used to play Pinners. |

Terminology

Rush Hour; A play in which the ball is out of play, either by foul ball, home run, or a misplay by the fielder, the fielder must throw the ball to the batter from where he stands or the batter may call stalling if the fielder is walking before he has thrown it in.

Rushies: A one-handed catch, leading to an automatic three outs. The player catching the ball with one hand is allowed to run towards the batter's box and throw the ball while the opposing team is in transition from offense to defense.

Stalling; When called the batting team is awarded a single without the batter, who would be up, having to sacrifice their turn in the order.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.