Mark Beaubien (1800-1881) was born in Detroit, younger brother of Jean Baptiste; married Monique Nadeau (1800-1847), with whom he had 16 children, 14 of whom survived their mother; then married Elizabeth Mathieu, with whom he had seven children.

|

Mark Beaubien, builder

Of Chicago's First Hotel. |

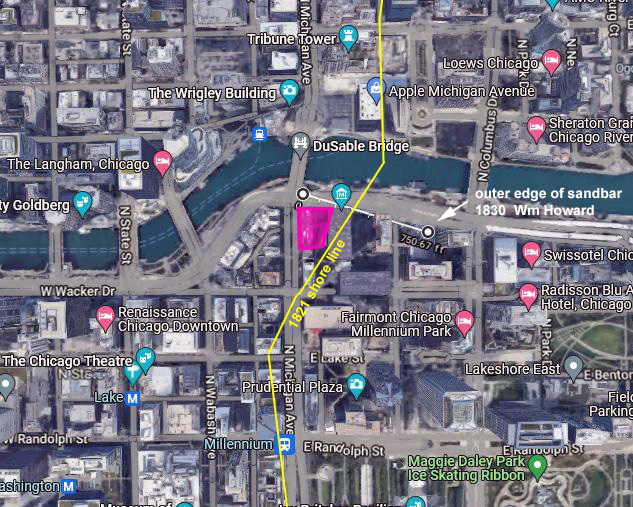

Mark came to Chicago in 1826 with Monique and their children and purchased a small log cabin on the south bank of the Chicago River near the Forks from James Kinzie. In 1829, he began to take in guests, calling his cabin the "Eagle Exchange Tavern." A fun-loving fiddle player, he loved to entertain his guests at night, tempting one to believe stories about his knack for boyish mischief. Mark was licensed to keep a tavern on June 9, 1830, and later voted on August 2. When the town plat was published that year, he found that his business was in the middle of a street and moved the structure to the southeast corner of Market Street (North Wacker Drive) and Lake Street.

He purchased from the government in 1830 lots 3 and 4 in block 31 on which his building stood, and the small block 30, later selling part of the land to Charles A. Ballard. He was listed on the Peoria County census of August 1830.

Mark Beaubien built the Eagle Exchange Tavern (later the Sauganash Hotel) in 1829 on the future site of the first Wigwam building and is regarded as the first tavern, hotel, and restaurant in Chicago. It was located at Wolf Point, the intersection of the Chicago River's north, south, and main branches, at Lake and Market Streets (North Wacker Drive). The Sauganash Tavern was one of the few grocers with billiard tables. He named the hotel in honor of his friend Billy Caldwell, whose Indian name was Sauganash.

The Green Tree Tavern wasn't built until 1833.

On June 6, 1831, at the new county seat (Chicago), he was granted a license to sell goods in Cook County, and his cabin sold Indian goods (arts & crafts). In the late summer of 1832, he rented his original log cabin, adjacent to his "Sauganash Tavern[1]," to the newly arrived Philo Carpenter for use as - Chicago's 1st - drugstore. An ardent enemy of alcohol, Carpenter soon moved out. Mark next rented the space to John S. Wright, and in 1833, the cabin became a school under Eliza Chappel's direction.

Mark and Mark, Jr. were listed among "500 Chicagoans" on the census Commissioner Thomas J.V. Owen took before the incorporation of Chicago as a town in early August 1833. Mark was one of the "Qualified Electors" who voted to incorporate the Town and, on August 10, voted in the first town election.

He received $500 in payment for a claim at the Chicago Treaty in September 1833. Mark became the first licensed ferry owner, and in 1834, he built his second hotel, the "Exchange Coffee House," at the northwest corner of Lake and Wells Streets. He placed an ad in the December 21, 1835, issue of the Chicago Democrat that read: "I, Mark Beaubien, do agree to pay 25 bushels of Oats if any man will agree to pay me the same number of bushels if I win against any man's horse or mare in the Town of Chicago, against Maj. R.A. Forsyth's bay mare, now in Town."

Listed in the 1839 City Directory as hotel-keeper, Lake Street. In 1840, Mark moved to Lisle, Illinois, with his family, where he acquired farmland from William Sweet south of Sweet's Grove and also a cabin located immediately west of the Beaubien Cemetery (a small cemetery on land set aside by Mark Beaubien on Ogden Avenue in Lisle). The cabin soon became Beaubien Tavern while it was still home to the residing family.

|

| The Beaubien Tavern, depicted by local painter Les Schrader, was the site of a toll station on the Southwest Plank Road that ran through Lisle to Chicago and later became Ogden Avenue. |

Mark was also listed as a U.S. lighthouse keeper in the 1843 Chicago City Directory. From 1851 to 1857 he used the Beaubien Tavern building as a toll station for the Southwest Plank Road (running from Lisle to Chicago), with his son collecting the toll.

Later, between 1859 and 1860, he was again the lighthouse keeper in Chicago. His address in 1878 was in Newark in Kendall County. During the last 10 years of his life, he was troubled by failing memory, much to his chagrin, because he loved to tell stories of the past; he was happiest in the company of old friends. Mark died on April 11, 1881, in his daughter Mary and son-in-law, Georges Mathieu's house, in Kankakee and was buried with his second wife in St. Rose Cemetery, in the oldest portion of Mound Grove.

His fiddle is preserved at the Chicago History Museum.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

[1] Sauganash Tavern: In the early days, while Mr. Beaubien kept a tavern, possibly the old Sauganash Tavern, when emigration from the east began to pour forth the stream which has not yet subsided, Mark's loft, capable of storing half a hundred men, for a night, if closely packed, was often filled to repletion. The furniture equipment, however, for a caravansary so well patronized, it is said, was exceedingly scant; that circumstance, however, only served to exhibit more clearly the eminent skill of the landlord. With the early shades of an autumn eve, the first men arriving were given a bed on the floor of the staging or loft, and, covering them with two blankets, Mark bade them a hearty goodnight. Fatigued with the day's travel, they would soon be sound asleep when two more would be placed by their side, and those "two blankets" would be drawn over these newcomers.

The first two were journeying too intently in the land of dreams to notice this sleight of hand feat of the jolly Mark, and as travelers, in those days, usually slept in their clothes, they generally passed the night without significant discomfort. As others arrived, the last going to bed always had the blankets. So it was that forty dusty, hopeful, tired, and generally uncomplaining emigrants or adventurous explorers who went up a ladder, two by two, to Mark Beaubien's sleeping loft were all covered with one pair of blankets. It is true, it was sometimes said, that on a frosty morning, there were frequent charges of blanket-stealing. Grumbling was heard, coupled with rough words similar to those formerly used by the army in Flanders, but the great heart of Mark was sufficient for the occasion, for, at such times, he would only charge half price for lodging to those who were disposed to complain.