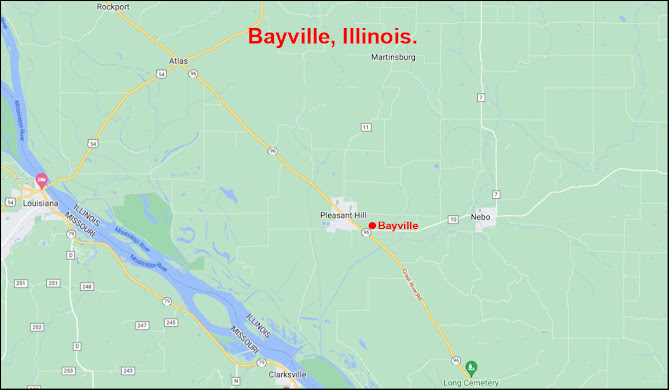

Indian Creek Village is within today's DeKalb County's Shabbona Lake State Park, located north of Ottawa and approximately 6 miles west of Illinois Route 23. The settlement was the site of the Indian Creek Massacre during the 1832 Black Hawk War. There are no residents.

During the Black Hawk War (1832), the Shabbona area, including Indian Creek Village, was in LaSalle County, Illinois. DeKalb County, Illinois, was founded on March 4, 1837.

|

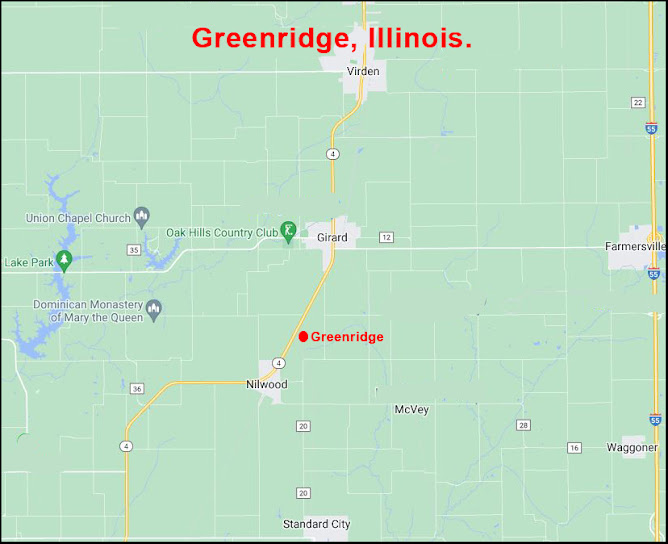

A cropped image from the 1836 "County Map of the States of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois,

and the Michigan Territory," showing the entire La Salle County area.

View the Library of Congress 1836 Map. |

The Indian Creek Massacre occurred on May 21, 1832, when a group of United States settlers in LaSalle County, Illinois, were attacked by a party of Indians. The massacre was sparked by the outbreak of the Black Hawk War, but it was not directly related to Sauk leader Black Hawk's conflict with the United States. Instead, the incident stemmed from a settler's refusal to remove a dam that jeopardized a food source for a nearby Potawatomi village. After the Black Hawk War began, between 40 and 80, Potawatomi and three Sauks attacked the settlement. Fifteen settlers, including women and children, were killed. Two young women kidnapped by the raiders were ransomed and released unharmed about two weeks later.

In the aftermath of the massacre, white settlers fled their homes for the safety of frontier forts and the protection of the militia. After the war ended, three Native men were arrested for the murders, but the charges were dropped after witnesses could not confirm that they had taken part in the massacre. Today, the site of the massacre is marked by memorials in Shabbona County Park in LaSalle County, about 14 miles north of Ottawa, Illinois.

The Indian Creek massacre stemmed from a dispute between U.S. settlers and a Potawatomi Native American village along Indian Creek in LaSalle County, Illinois. In the spring of 1832, a blacksmith named William Davis dammed the creek to provide power for his sawmill.

Meaueus, the principal chief of the small Potawatomi village, protested to Davis that the dam prevented fish from reaching the village. Davis ignored the protests and assaulted a Potawatomi man who tried dismantling the dam. The villagers wanted to retaliate, but Potawatomi chiefs Shabbona and Waubonsie managed to keep the peace, convincing the villagers to fish below the dam.

Meanwhile, in April 1832, the Sauk leader named Black Hawk (The "Life of Black Hawk" as dictated by himself.") led a group of Sauks, Meskwakis, and Kickapoos known as the "British Band" across the Mississippi River into the U.S. state of Illinois. Black Hawk's motives were ambiguous, but he hoped to avoid bloodshed while settling on land ceded to the United States in a disputed 1804 treaty.

Black Hawk hoped that the Potawatomi people in Illinois would support him. In February 1832, he invited the Potawatomi to join him in a coalition against the United States. Although Potawatomi had grievances stemming from the expansion of the United States into Indian land, Potawatomi leaders feared that the United States had become too powerful to oppose by force. Potawatomi chiefs urged their people to stay neutral in the coming conflict, but, as in other tribes, chiefs did not have the authority or power to compel compliance. Potawatomi leaders worried that the tribe would be punished by supporting Black Hawk. At a council outside Chicago on May 1, 1832, Potawatomi leaders, including Billy Caldwell, "passed a resolution declaring any Potawatomi who supported Black Hawk, a traitor to his tribe." In mid-May, Potawatomi leaders told Black Hawk they would not aid him.

Hostilities in the Black Hawk War began on May 14, 1832, when Black Hawk's warriors soundly defeated Illinois militiamen at the Battle of Stillman's Run. Potawatomi chief Shabbona worried that Black Hawk's success would encourage Native attacks on American settlements and that Potawatomi would be held responsible. Soon after the battle, Shabbona, his son, and his nephew rode out to warn nearby American settlers that they were in danger. Many people heeded the warnings and fled to Ottawa for safety, but William Davis, the settler who had built the controversial dam, decided to stay. Davis convinced some of his neighbors that danger was not imminent. Twenty-three people remained at the Davis settlement, including the Davis family, the Hall family, the Pettigrew family, and several other men.

On May 21, 1832, a party of about forty to eighty Potawatomi attacked the Davis house. Three Sauks from Black Hawk's Band accompanied the Potawatomi. It was late afternoon when the inhabitants at the settlement saw the group of Native American warriors approach the cabin, vault the fence and sprint forward to attack. Several men and boys worked in the fields and the blacksmith's shop when the attack began. Several men who rushed to the house during the attack were killed, but six young men escaped the slaughter by fleeing. In all, fifteen settlers were killed and scalped. "The men and children were chopped to pieces," writes historian Kerry Trask, "and the dead women were hung by their feet," and their bodies mutilated in ways too gruesome for contemporary observers to record in writing.

Most modern scholars do not name the leader of this attack. According to historian Patrick Jung, the attack was led by the Potawatomi man who had been assaulted at the dam by Davis. Still, Jung did not identify this Potawatomi by name. Historians Kerry Trask and John Hall identified the man who had been assaulted as Keewassee. Still, they did not specifically describe him as taking part in the attack, nor did they name a leader of the attack. Historian David Edmunds wrote that the attack was led by Toquame and Comee, two Potawatomi warriors. According to Jung, however, Keewasse, Toquame, and Comee were three Sauk warriors who accompanied the Potawatomi during the attack.

In 1872, amateur historian Nehemiah Matson wrote that the raid was led by a man named Mike Girty, supposedly a mixed-race son of Simon Girty. But a 1960 profile of Matson stated, "Because of his indiscriminate mixing of fact and legend, however, scholars generally discount his books as valid sources." In a 1903 book, Frank E. Stevens dismissed Matson's story, writing, "The statement by Matson that one Mike Girty was connected with the Indian Creek massacre is incorrect." Modern scholarly accounts of the Black Hawk War and the Indian Creek massacre were mentioned by Mike Girty.

Two young women from the settlement, Sylvia Hall (19) and Rachel Hall (17), were spared by the attackers and taken northwards. At one point, Sylvia fainted when she recognized that one of the warriors carried her mother's scalp. After an arduous journey of about 80 miles, they arrived at Black Hawk's camp. The Hall sisters were held for eleven days at Black Hawk's camp, where they were treated well. Black Hawk insisted that the three Sauks with the Potawatomi had saved the Hall sisters' lives in his memoirs dictated after the war. Black Hawk recounted:

They were brought to our encampment, and a messenger sent to the Winnebago, as they were friendly on both sides, to come and get them, and carry them to the whites. If these young men belonging to my Band had not gone with the Potawatomi, the two young squaws would have shared the same fate as their friends.

A Ho-Chunk chief named White Crow negotiated their release. Like some other area Ho-Chunks, White Crow was trying to placate the Americans while clandestinely aiding the British Band. U.S. Indian agent Henry Gratiot paid a ransom for the girls of ten horses, wampum, and corn. The Hall sisters were released on June 1, 1832.

The Indian Creek massacre was one of the Black Hawk War's most famous and well-publicized incidents. The killings triggered panic in the white population nearby, and people abandoned settlements and sought refuge inside frontier forts, such as Fort Dearborn in Chicago.

On May 21 or 22, the people in Chicago, including those who had fled, dispatched a company of militia scouts to ascertain the situation along the Chicago-Ottawa trail. The detachment, under the command of Captain Jesse B. Brown, came upon the mangled remains of the 15 victims at Indian Creek on May 22. They buried the dead and continued to Ottawa, where they reported their gruesome discovery. As a result, the Illinois militia used the event to draw more recruits from Illinois and Kentucky.

After the war, three Indians were charged with murder for the Indian Creek massacre and warrants were issued at the LaSalle County Courthouse for Keewasee, Toquame, and Comee. The charges were dropped when the Hall sisters could not identify the three men as part of the attacking party. In 1833, the Illinois General Assembly passed a law granting both Hall sisters 80 acres of land each along the Illinois and Michigan Canal as compensation and recognition for their hardships.

In 1877, William Munson, who had married Rachel Hall, erected a monument where the massacre's victims were buried. The memorial, located 14 miles north of Ottawa, Illinois, cost $700 to erect. In 1902, the area was designated as Shabbona Park, and $5,000 was appropriated by the Illinois legislature for the erection and maintenance of a new monument. On August 29, 1906, a 16-foot granite monument was dedicated in a ceremony attended by four thousand people. Shabbona County Park, separate from Shabbona Lake State Park in DeKalb County, is located in northern LaSalle County, west of Illinois Route 23.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.