Hatfield Honored by Abe Lincoln. President Introduced Him to Both Houses of Congress—Story of the Famous Escape of 131 Men.

While eloquent members of the Nebraska state senate was eulogizing Abraham Lincoln on the 100th birthday of the martyred president, there sat silent, but attentive to the proceeding one member of that body who had the honor of having been introduced by Lincoln to both branches of congress.

That man was Senator John D. "J.D." Hatfield [D] (1909-1911) of Antelope county. Few persons on the occasion of the speechmaking in the senate knew that Senator Hatfield had been thus honored or was aware of the reasons why President Lincoln had paid him this tribute.

|

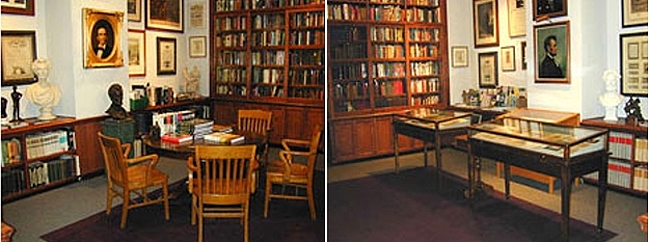

| Captain John D. Hatfield of Neligh, Nebraska. Escaped from Libby Prison and was Honored by President Lincoln. |

Some may have noticed a little bronze button on the lapel of the senator's coat, but he had been among his fellow senators only a short time and had been so quiet that it was not even known that he claimed the honor of having met the Lincoln who is now the ideal of the American people and of the world Senator Hatfield is like four of the other members of the senate.

He had the fortune to serve in the war of the rebellion in defense of the union. He was one of the 131 brave Union prisoners-of-war to escape from captivity by planning and digging a tunnel from Libby prison to the open air of freedom. Captain Hatfield was one of the men who escaped and made their way to the Union lines. A few days later, Hatfield was personally invited to the White House by President Abraham Lincoln to be shown every honor.

Libby Prison

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Luther Libby was running a ship supply shop from the corner of a large warehouse in Richmond, Virginia. In need of a new prison for captured Union officers, Confederate soldiers gave Libby 48 hours to evacuate his property. The sign over the north-west corner reading "L. Libby & Son, Ship Chandlers" was never removed, and consequently, the building and prison bore his name. Since the Confederates believed the building inescapable, the staff considered their job relatively easy.

Death Lottery

It was also his fortune while in Libby Prison at Richmond, Virginia to be one of the prisoners of the rank of captain who drew lots one of the most gruesome of prizes, the privilege of being hanged by the neck till dead, a fate which the rebel authorities proposed in retaliation for the hanging of two southern spies found within the union lines Neither of the two little black beans in the lottery fell to him.

Captured In a Charge

How Senator Hatfield came to meet President Lincoln dates back to Jackson, Mississippi, when by the blunder of some superior officer his troops were ordered to charge strong breastworks of the confederates.- He obeyed, as captain of Company H, 53rd Illinois, and while many of the soldiers remained on the battlefield, dead or wounded, he and about 200 others went over the breastworks. It is needless to say he stayed there as a prisoner of war. While in the hands of the southern men who commanded troops in the field he was well treated but his transfer to Libby prison at Richmond, Virginia. was a different story. Immediately after his capture, he asked permission to go back over the field. Under a guard, he was allowed this privilege. What he saw there was the most distressing sight of his life. His colonel and the lieutenant colonel were among the dead.

He remained seven months in Libby before the historical escape occurred. The life there was not to be compared to that at Andersonville, but it was bad enough. The open windows [of the large tobacco warehouse let in cold and one night the temperature fell to 4° below zero. The prisoners had nothing but one blanket and a bare floor to sleep upon and they had to run about the prison all night to keep from freezing to death.

Plan to Escape.

"I never knew who dug the tunnel," said Captain Hatfield, "for the reason that we worked at night and never were able to recognize each other in the day time.

By removing a stove on the first floor and chipping their way into the adjoining chimney, the officers constructed a cramped but effective passage for access to the eastern basement. Once access between the two floors was established, the officers set about plans to tunnel their way out. There were fifteen men on the work and it required fifty-one days and nights.

Among the number was one civil engineer who did some calculating for us, but after all, we started to come out of the ground with the tunnel too soon before we had got past a high board fence in a vacant lot where we desired to have the exit.

History gives the credit to Colonel Rose for planning the escape, but it belongs to others as I understand it. The men who started it found the Work too slow and called in others to help. I was confided in after the work started. The basement below where we were imprisoned was used as a storeroom and we dared not use it, so a sloping tunnel was started through the brick wall to a basement opposite our quarters. This second basement was over 100 feet long and was lighted only by one door with dirty glass. The farthest end where it was dark and where some hogsheads and barrels were piled, was the place chosen for the entrance to the main tunnel. It was planned to go under the street and come out in a vacant lot behind a store, the proposed exit being behind a high board fence.

"You can imagine it was slow work. Two men labored in the day time and two at night. We had nothing to work with except a case knife and a chisel. To haul the dirt out of the place we had to use a wooden spittoon. To this, we tied a strip of a blanket to haul it out and to haul it into the tunnel. Every time the work stopped the hole in the wall had to be stopped up and ashes were used to make the wall look solid. Then we had to prevent the guards from missing the two men who were constantly on the work. The count taken in the morning and at night was not by actual count, but by squares of men lined up four abreast. To make the square look full one prisoner would playfully jostle another to one side and sometimes a hat would be held up to represent a man in the squad.

We started to throw the earth taken from the tunnel into a sewer that emptied into a canal near the prison, but this was abandoned because the dirt discolored the water and made us afraid our plans would be discovered. The dirt was piled in the dark end of a large basement room behind hogsheads and barrels.

The Tunnel Finished

"The supreme moment came on the evening of February 9, 1864. At eight o'clock prisoners began to enter the tunnel to make their strike for liberty. The hole was so narrow that a big man had difficulty in worming his way through. There was danger that men would smother to death in the hole and stop our way to the open air. I entered the tunnel at 11 o'clock at night. I did not care to start earlier for fear of the patrol through the city. A large man in front of me puffed and groaned in his efforts to wiggle through the hole. One big man had to be assisted. Others crept up behind him and he put his feet on the shoulders of the man next to him and pushed, while the man in front of him pulled with all his might on his arms.

"One hundred and nine passed through the tunnel by daylight. Before I wont out I loosened and pulled out of position two bars to a window. This was planned in the hope that the rebels would not find our exit, but would think we got out of the window and that the guards would be blamed. Then it was hoped other prisoners might use the tunne! the next night. It turned out as we supposed. When the prisoners were missed in the morning the guards were placed under arrest for negligence. Diligent search was made all day for the means of escape, but nothing except the disarranged bars of the window were found till some one saw the hole in the vacant lot. Then a negro was put into it and he worked his way back into the prison through the tunnel we had used.

"It was never accurately known how many of the 109 got into the union lines. The number was between 37 and 56. The escaped men went in twos or singly, i was alone and was five days traveling ninety miles to the union lines at Williamsburg, Va., where the Seventh New York cavalry took me in charge. I was bareheaded and barefooted and badly frozen and had only one meal of victuals in five days.

"It is no easy job to hide in the winter in the daytime. By traveling at night and hiding by day I managed to get through. The open fields, especially if they were overgrown I found the best places to hide in. The ground was frozen and made a nice place to lie in. As what clothing I had was already frozen I did not mind the frozen ground. A strong constitution was probably all that enabled me to endure the hardship of the trip. Frequently I could see the rebels searching in skirmish lines through the timber and fields for the escaped men. This kept me alert and I had little chance to forget the seriousness of the situation.

Negro Furnishes Aid

"The rebels had destroyed all of the boats on the Chickahominy River that I had to cross and I was looking for cordwood or some other means of floating across because I knew I would die if I attempted to swim. Just then I heard someone coming through the brush. I hid under the boards of a little boat landing and when I thought the person approaching was near me I jumped out and grasped him by the neck and told him I would kill him if he tried to getaway. The only weapons I had were a butcher knife and a cane.

"Good Lord, Massey spare my life," said the man. Then I knew he was a negro, and I did not harm him. I told him who I was and what I wanted and he said he had a boat hidden in the brush. We carried it to the river and he rowed me over and said he would go back and get something for me to eat. True to his word he came back with a nice supper of cornbread and bacon, which he had had his wife cook in their cabin. That was the only meal I had on the way.

For two days I remained at Williamsburg and then went to Fortress Monroe, where I remained one day. General Ben Butler was in command there. I had never seen him but was able to recognize him from ' descriptions of his peculiar countenance. He gave me a pass to Washington, where I arrived at 7 o'clock in the evening. The return of one of the Libby prison men appeared to create some commotion. At 8 o'clock in the evening, President Lincoln sent an orderly and invited me to come to the White House and stay overnight. I was poorly clad and felt unfit physically to appear before him and asked the orderly to present my excuse. The next morning while passing up Pennsylvania avenue a Jewish merchant came out and asked me if I was the man who came in yesterday. He wanted to sell me a uniform, but I told him I was poor and had no money. He took me in the store and insisted on giving me a uniform of my rank with the understanding that if I did not get my pay he would let me keep it for free.

I visited a barbershop and got my hair cut and with the new uniform on my back, I felt better and must have looked somewhat like a human being.

Interview With Lincoln

A brother of Governor Morton of Indiana introduced himself to me and offered to go with me to the white house. He said he was personally acquainted with the president. I accepted his offer. I can never forget how Lincoln looked. He sat down in a chair and wrapped his long loose looking legs in a peculiar way, one behind the other under the chair rungs.

"Captain," he said, "I always said if I found a man homelier than myself I would kill him. I believe I have found him."

"All right," I said, "I am not much good; I am about played out anyway."

"I'll give you one chance," he said, "I'll leave it to Mrs. Lincoln."

"If you do, my life will be spared," I replied.

He called for Mrs. Lincoln and when she entered the room, he introduced me and said, "Now, haven't I found him?"

"No," she replied, "If he were well he would be a better-looking man than you."

Lincoln then asked me questions about the escape of the prisoners and about myself. This took up the time till noon and he had me remain for dinner. He asked me if I had ever seen Washington and when I told him I had not, he offered to take me about the city. He first took me to congress, which was then in session, and introduced me to both houses. We visited all the places of interest. He took me to the paymaster general and there I drew pay amounting to $1,015 ($16,850 today). He took me to Secretary of War Stanton and told him to give me a leave of absence for thirty days and a free pass to Illinois. I suggested that I would not be in condition for service in thirty days, but Lincoln said under general orders a leave could not be granted for a longer period. He told me to report my condition and he would leave it to my honor and if necessary extend the leave of absence. I got one extension signed by President Lincoln and then went back to the service and marched with Sherman to the sea.

Butler's Famous Threat

"While with General Butler I asked about his threat to hang General Fitzhugh Lee and Captain Winder, confederate prisoners in his charge, if the rebels carried out their threat to hang Captain Sawyer and Captain Flynn of Libby prison. He said he surely would have done it. I suggested that he would not because Lincoln would not have let him.

"I would have had them shot first," said General Butler, "and then reported to Lincoln what I had done." "I never knew why Captain Sawyer and Captain Flynn were not hanged by the rebels, but I understood that the threat of General Butler saved their lives. Before I left Libby prison I heard the rebels say of General Butler, "The old brute will do it."

Letters from Libby Prison [Runtime 16:11]

The Libby Prison Break was the largest and most successful of the Civil War.

Nebraska State Journal, February 14, 1909

Edited by Neil Gale, Ph.D.