The History of Gail Borden, Jr.

Gail Borden's story begins in Norwich, New York, where he was born in 1801.

|

| Gail Borden, Jr. 1801-1874 |

After a few years, the family moved to Kentucky and then to Indiana. In his early 20s, Gail followed his brothers south, eventually working as a surveyor in Mississippi. By 1835, Borden—now married—had settled in Texas, working first as a surveyor and then as a newspaper editor, which is interesting since his only formal education took place during his two years in Indiana, learning to be a surveyor.

"Telegraph and Texas Planter" Newspaper (1835-1837)

In February 1835, Gail and his brother John Borden partnered with Joseph Baker to publish one of the first newspapers in Texas. Although none of the three had any previous printing experience, Baker was considered "one of the best-informed men in the Texian colony on the Texas-Mexican situation." The men based their newspaper in San Felipe de Austin, centrally located among the colonies in eastern Texas. They ran the first issue under the "Telegraph and Texas Planter" banner on October 10, 1835, days after the Texas Revolution began. However, the later issues bore the name Telegraph and Texas Register. As the editor, Gail Borden worked to be objective.

Soon after the newspaper began publishing, his brother John Borden left to join the Texian Army, and their brother Thomas took his place as Borden's partner. Historian Eugene C. Barker describes the Borden newspaper as "an invaluable repository of public documents during this critical period of the state's history." The early format of the paper was three columns to a page with a total of eight pages. The Telegraph printed official documents and announcements, editorials, local news, reprints of articles from other newspapers, poetry, and advertisements.

As the Mexican Army moved east into the Texian colonies, the Telegraph was soon the only newspaper in Texas still operating. Their 21st issue was published on March 24. This contained the first Texans who died at the Battle of the Alamo. On March 27, the Texas Army reached San Felipe, carrying word that the Mexican advance guard was approaching. A later editorial in the Telegraph said the publishers were "the last to consent to move." The Bordens dismantled the printing press and brought it with them as they evacuated with the rear guard on March 30. The Bordens retreated to Harrisburg. On April 14, as they were in the process of printing a new issue, Mexican soldiers arrived and seized the press. The soldiers threw the type and press into Buffalo Bayou and arrested the Bordens. The Texas Revolution ended days later.

Lacking funds to replace his equipment, Borden mortgaged his land to buy a new printing press in Cincinnati. The 23rd issue of the Telegraph was published in Columbia on August 2, 1836. Although many had expected Columbia to be the new capital, the First Texas Congress chose the new city of Houston instead. Borden relocated to Houston and published the first Houston issue of his paper on May 2, 1837.

The newspaper was financially unstable, as the Bordens rarely paid their bills. In March, Thomas Borden sold his interest in the enterprise to Francis W. Moore Jr., who took over as chief editor. Three months later, Gail Borden transferred his shares to Jacob W. Cruger.

Borden was an inventor, although only sometimes successful. In the early 1840s, he experimented with disease cures and mechanics. His wife, Penelope, died of yellow fever on September 5, 1844. Frequent epidemics swept through the nation, and the disease had a high rate of fatalities during the 19th century. Borden began experimenting with finding a cure for the disease via refrigeration, and no one understood how it was transmitted.

The "Terraqueous Machine"

One of his inventions was the Terraqueous Machine (of land and water). Accounts of his first—and only—journey are not kind.

In the late 1840s, a crowd of curious onlookers and a few hardy volunteers gathered on a Galveston, Texas, beach to meet Gail Borden and witness the unveiling of his new amphibious machine.

The machine was rigged with a mast, a square sail, a rudder, and a steering device for the front wheels. This sail-powered wagon was designed to travel over land and sea but was designed more specifically for the western prairies. Borden enlisted some friends to ride with him on the machine's maiden voyage, but whether those people remained friends after the demonstration is still being determined. The machine's sail caught the wind and zipped along at a clip fast enough to terrify his fellow passengers. They panicked when Borden steered into the waves, and the Terraqueous Machine tumped over, spilling its inventor and his passengers into the surf. Anxious moments passed until some drenched and unlucky passengers emerged from the waves onto the shore. When asked where Borden was, one of the disillusioned riders said, "I sincerely hope he has drowned." Borden didn't drown. The Terraqueous Machine was his first invention, and though it never caught on, the idea lingered.

Meat Biscuit aka Soup-Bread

In 1849, Borden turned his attention to inventing a stable meat biscuit for travelers and folks in rural America. Specifically, he created a Meat Biscuit or "Portable Desiccated (having had all moisture removed) Soup-Bread," similar to Native American pemmican. The meat biscuits were immensely popular during the California Gold Rush because the 49ers needed compact, lightweight, non-perishable supplies, and Borden's meat biscuits fit the bill. The idea was to preserve the concentrated nutritional properties of flesh meat, combine it with flour, and bake it into biscuits. One pound of this bread contains the extract of more than five pounds of the best meat, and one ounce of it will make a pint of rich soup. The idea was to preserve the concentrated nutritional properties of flesh meat, combine it with flour, and bake it into biscuits. One pound of this bread contains the extract of more than five pounds of the best meat, and one ounce of it will make a pint of rich soup. Biscuits were made from beef, veal, fowl flesh, oysters, etc., and were not intended to be eaten.

In 1851, Borden traveled to the 1851 London World's Fair. The Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations, also known as the Great Exhibition or the Crystal Palace Exhibition, was an international exhibition in Hyde Park, London, from May 1 to October 15, 1851. His biscuits were well-received, winning a Gold Medal at the Great Council Exhibit. He also experimented with coffee, tea, and cocoa. Borden was able to make concentrates from apples, currants, and grapes.

|

| Meat Biscuit aka Soup-Bread. The recipe is at the end of this article. |

In a letter dated March 23, 1850, to Dr. Ashbel Smith, Borden relates the way he made this discovery and describes how to prepare the Soup-Bread and how it tastes:

"I was endeavoring to make some portable meat glue (the common kind known) for some friends who were going to California—I had set up a large kettle and evaporating pan, and after two days labor I reduced one hundred and twenty pounds of veal to ten pounds of extract, a consistency like melted glue and molasses; the weather was warm and rainy, it being the middle of July. I could not dry it either in or out of the house and unwilling to lose my labor, it occured to me, after various expedients, to mix the article with good flour and bake it. To my great satisfaction, the bread was found to contain all the primary principles of meat, and with a better flavor than simple veal soup, thickened with flour in the ordinary method.The nutritive portions of beef or other meat, immediately on its being slaughtered, are, by long boiling, separated from the bones and fibrous and cartilaginous matters: the water holding the nutritious matters in solution, is evaporated to a considerable degree of spissitude—this is then made into a dough with firm wheaten flour, the dough rolled and cut into a form of biscuits, is then desiccated, or baked in an oven at a moderate heat. The cooking, both of the flour and the animal food is thus complete. The meat biscuits were prepared to have the appearance and firmness of the nicest crackers or navy bread, being as dry, and breaking or pulverizing as readily as the most carefully made table crackers. It is preserved in the form of biscuit or reduced to coarse flour or meal. It is best kept in tin cases hermetically soldered up; the exclusion of air is not important, humidity alone is to be guarded against.For making soup from a meat biscuit, a batter is first made of the pulverized biscuit and cold water—this is stirred into boiling water—the boiling is continued some ten or twenty minutes—salt, pepper, and other condiments are added to suit the taste, and the soup is ready for the table.I have eaten the soup several times,—it has the fresh, lively, clean, and thoroughly done or cooked flavor that used to form the charm of the soups of the Rocher de Cancale. It is perfectly free from that vapid unctuous stale taste that characterizes all prepared soups I have heretofore tried at sea and elsewhere. Those chemical changes in food which, in common language, we denominate cooking, have been perfectly affected in Mr. Borden’s biscuit by the long-continued boiling at first, and the subsequent baking or roasting. The soup prepared of it is thus ready to be absorbed into the system without loss, and without tedious digestion in the alimentary canal, and is in the highest degree nutritious and invigorating."

The recipe for these biscuits is at the end of the article.

Sailing back from London's World Fair, The Great Exhibition in Hyde Park in 1851, Borden was horrified seeing several children and two cows die from drinking contaminated milk; the milk wasn't fresh... but had not soured yet. He wondered if there was a way to preserve milk indefinitely and found inspiration from the Shakers with whom he had spent some time, possibly in Kentucky. He recalled that the Shakers had developed a process of evaporating fruit juice by vacuum and making it "shelf-stable," in today's terms.

The invention of canned milk can be attributed to Gail Borden in the early 1850s. He is credited with inventing condensed milk, which has had some of the water removed, making it thicker and more shelf-stable. Borden was motivated by the need to find a way to preserve milk, as it spoiled quickly at the time and was often contaminated. Condensed milk was initially sweetened with sugar and marketed as a healthy and convenient food for infants and children. Borden's method involved heating milk to remove a significant portion of its water content, then sealing it in airtight cans. This process killed harmful bacteria and extended the shelf life of the milk to several years. Initially known as "Eagle Brand," his invention was initially met with skepticism, but it soon gained popularity and became widely used by soldiers during the American Civil War. In short order, he founded the New York Condensed Milk Company. Borden's invention of condensed milk was a major breakthrough in food preservation. It made it possible to transport and store milk safely, improving millions of lives.

sidebar

Al Capone and his Brother Ralph are responsible for milk expiration dating. Capone convinced the Chicago City Council to pass a law in 1933 that clearly stamped the date on milk bottles so that the consumer could read and understand it.

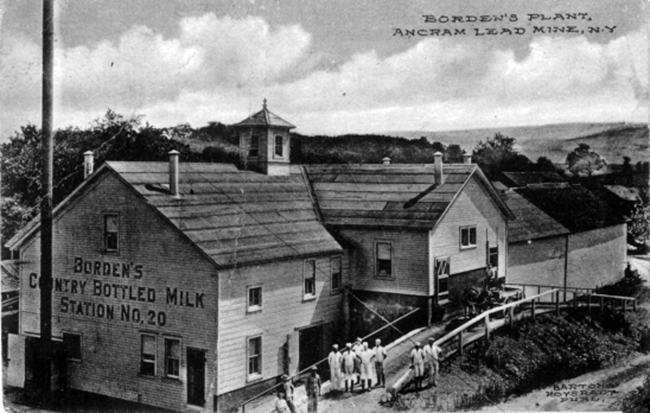

Borden opened factories across New York State, including Craryville, Copake, and Ancram.

|

| Borden's Country Bottled Milk Station No. 20, Ancram, New York, Plant. |

Borden was enshrined in the "Inventors Hall of Fame" in 2008 for inventing condensed milk, U.S. Patent No. 15,553, on August 19, 1856.

By 1858, Eagle Brand Condensed Milk was a trusted brand selling briskly. The Union Army supplied the troops with Eagle Brand during the Civil War, an enormous windfall for Borden.

|

| Advertisement for Gail Borden's Eagle Brand Condensed Milk from an 1898 guidebook for travelers in the Klondike Gold Rush. |

In later years, Borden returned to Texas, where he supported the poor, minorities, and teachers. He became a well-known philanthropist, and he helped organize a school for negroes. Borden also helped build six new churches. He died in Borden, Texas, 1874 and was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in New York.

|

| An amber Signature Quality Borden's Dairy Farm Milk Bottle with Gail Borden's signature (bottle age unknown). |

Borden's was once the largest U.S. producer of dairy and pasta products. He also sold snacks, processed cheese, jams, jellies, and ice cream. Borden's consumer products division sold wallpaper, adhesives, plastics, and resins. The company sold Elmer's Glue and Krazy Glue. The Borden Brand eventually became the Eagle Brand and sold such labels as Mott's and Cremora. Smucker's acquired Eagle Brands in 2007.

Gail Borden invented a lot of useful products. Throughout his life, he always respected science. He was a very reputable man.

The New York Condensed Milk Company lived on, and in 1899, the company renamed itself Borden Milk Company in his honor.

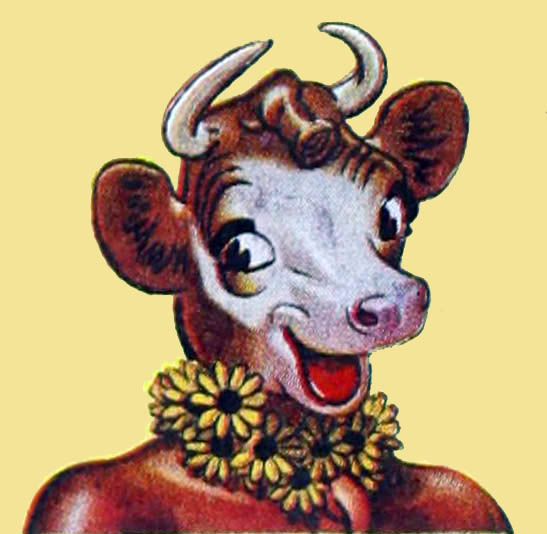

Elsie, the Cow, was the first Mascot of Borden Dairy Company, appearing in 1936 to symbolize the "perfect dairy product." Since the demise of Borden in the mid-1990s, the character has continued to be used in the same capacity for the company's partial successors, Eagle Family Foods (owned by J.M. Smucker) and Borden Dairy.

|

| Elsie the Cow in a 1948 ad. |

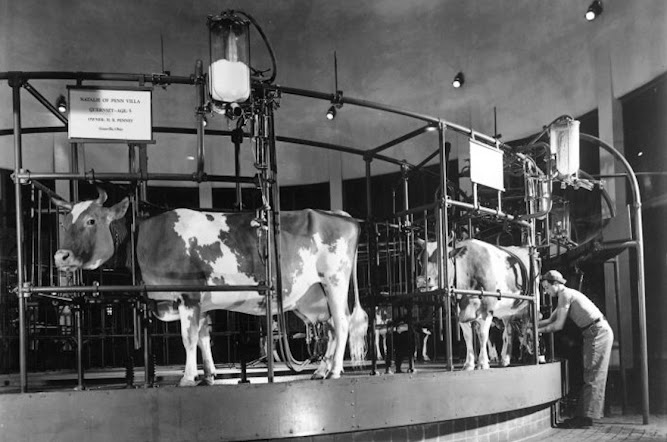

The first Elsie was a registered Jersey heifer selected while participating in Borden's 1939 New York World's Fair "Rotolactor" exhibit (a cow 'merry-go-round' that could milk cows much faster and more efficiently).

|

| The "Rotolactor" was displayed in the Futuristic Farming exhibit at the 1939 New York "World of Tomorrow" World's Fair. |

When the other cows were not being milked, Elsie would ride the Rotolactor alone, wearing her trademark chain of daisies around her neck and a blanket with her name on her back—waving her tail to the crowd.

Elsie was a smash, and the Borden display was a big success. Elsie gave a "Bovine Ball" for the press at the season's end, which proved so popular that other appearances followed.

At the height of her career, Elsie was noted as the most famous icon in America, not an easy feat when you are up against such formidable competitors as The Campbell Soup Kids, the Marlboro Man, and The Jolly Green Giant.

According to Ad Age magazine, Elsie became one of the top 10 advertising symbols of the twentieth century.

Sniff the spicy fragrance when it comes out of the oven! Roll the hearty, country-kitchen flavor over your tongue! A-s-h! It's Borden's None Such Mince Meat Pie!Borden's None Such Mince Meat is made of 20 choice ingredients—hand-picked apples, sun-wrinkled raisins, tart citrus peel, and spices from the far corners of the earth—aged and blended in a New England recipe 56 years old (from 1884). It's spicier, fruitier than "ordinary" mince meat—yet costs but a few cents more!So demand genuine Borden's None Such Mince Meat. Look for the None Such Girl on the bright Red package!

A new idea book from Borden. "The Touch of Taste from None Such Mince Meat: a New Idea Book from Borden" was published in 1977.

Borden's "HEMO" Chocolate Powder (1942-1946)

Here's HEMO—made for every man, woman, and child who needs more vitamins and minerals to get a new kick out of life!

Hemo has a deep, rich, malty flavor. Tastes like the slickest malted milk you ever drank—only better!

But HEMO is more—far more—than just a grand-tasting drink! HEMO is crammed with vitamins and minerals—enough to really do some good! One glass of Hemo daily—yes, just one—gives you one-half the total daily adult requirements of Vitamins A, B1, D, and G, plus iron! And extra needed calcium and phosphorus, too!Added to a usual diet, that makes up almost any shortage of all these vital food elements! Enough HEMO to make one drink costs only 2½¢!Start drinking HEMO today. Lean back and enjoy every sip. See if you don't start feeling better, looking better, and tackling each day with more pep! Get HEMO now! 24 delicious drinks at your grocer or druggists for 59¢.

Elsie had a fictional cartoon mate, Elmer the Bull, whose drawing is on every bottle of Elmer's Glue-All. Elmer was created in 1940 and lent to Borden's then-chemical division as the mascot for Elmer's Products.

The pair were given offspring Beulah and Beauregard in 1948 and twins Larabee and Lobelia in 1957.

Elsie has been bestowed honorary university degrees as "Doctor of Bovinity," "Doctor of Human Kindness," and "Doctor of Ecownomics." In Wisconsin, home of the Dairy Princess, Elsie was named "Queen of Dairyland."

sidebar

The Wisconsin "Queen of Dairyland" gave the dairy industry hundreds of thousands of dollars worth of free publicity.

The Seneca (Iroquois) Tribe named Elsie (Iroquois: awsғ:iyo jó:sgwa:ön = Beautiful Flowers Cow) an honorary Chief. She holds keys to over 200 cities.

But best of all, Elsie helped sell more than $10 million in U.S. War Bonds.

Tragically, on April 16, 1941, Elsie was traveling on a highway when her truck was slammed from behind, severely damaging her vertebrae. She was rushed back to Plainsboro, New Jersey, to a veterinarian. Various treatments were considered, including traction, but nothing was to be done. Elsie was euthanized on April 20 and buried at the Walker-Gordon Dairy behind the carpenter shop. A headstone was later created to mark her resting place.

Elsie the Cow TV Commercial, Circa 1950.

In 1997, Elsie and the Borden name were sold to the Dairy Farmers' Association of America. Her "i-cow-nic" image is still in use on various cheese products. People still love Elsie. She is definitely the Queen among cows, and that's no bull.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Borden's Homemade Meat Biscuits aka Soup-Bread Recipe

INGREDIENTS

- Bouillon: Beef, Chicken, Fish, Ham, Lobster, Turkey, Vegetable. (Bouillon Paste)

- Flour

- Water

INSTRUCTIONS

- Mix flour with bouillon. If the bouillon is a paste, mash it with a spoon until it is thoroughly mixed and looks like whole wheat flour. Do not use too much flour; you are not making bread. You are making a stabilizer for the bouillon.

- Add just enough cold water to make a very, very stiff dough. It should hold together but not be sticky.

- Roll out quite thinly and cut into pieces.

- Bake at 300° F. for 30 minutes or until completely dry and hard.

PREPARING THE BISCUITS

To make into soup, smash it up in cold water with something heavy, like a meat tenderizer, then boil in more water.

CRITICS COMMENTARY

It was okay! The broth was pretty weak in the end, but more biscuits would have helped that. I thought the flour would have thickened the soup, but instead, it made little crumbly sediment, which was expected. I can see how this would be a useful addition to a wagon headed west. These meat biscuits never became popular, but more than one wagon included a barrel of them amongst their supplies. (Anonymous)