Thursday, August 27, 2020

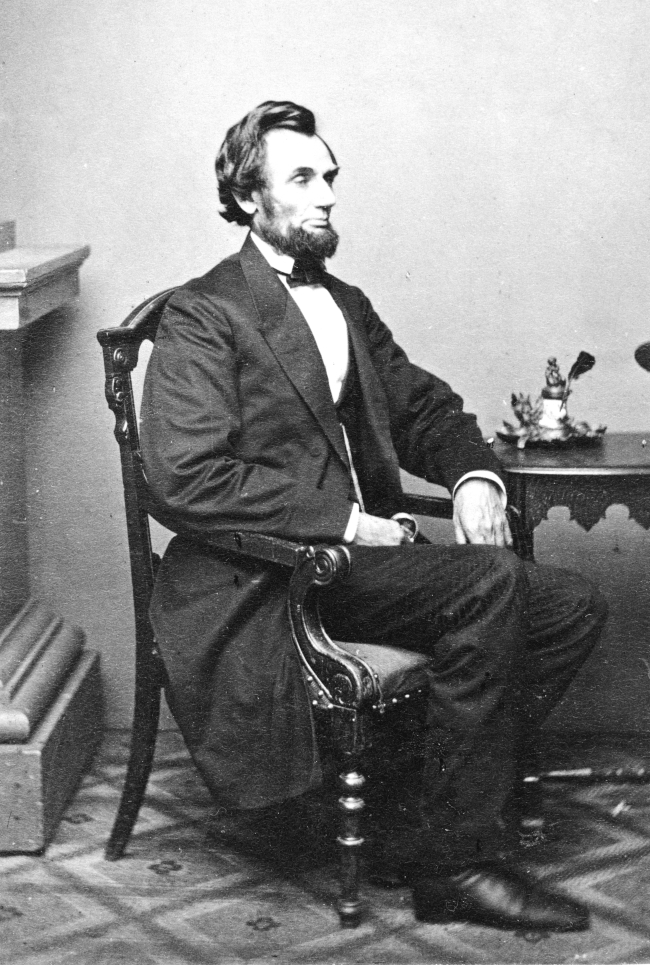

Portrait of Abraham Lincoln that was used as a campaign badge (buttons) during the 1860 presidential election.

Saturday, August 22, 2020

An Interesting Incident with President Lincoln Signing the Emancipation Proclamation.

"I have been shaking hands since nine o'clock this morning, and my right arm is almost paralyzed. If my name ever goes into history it will be for this act, and my whole soul is in it. If my hand trembles when I sign the Proclamation, all who examine the document hereafter will say, 'He hesitated.'"

Friday, August 21, 2020

A Humorous Speech — Lincoln in the Black Hawk War.

The friends of General Lewis Cass, when that gentleman was a candidate for the presidency[1], endeavored to endow Abraham with a military reputation. Mr. Lincoln, at that time a representative in Congress (1847-1849), delivered a speech before the House, which, in its allusions to General Cass, was exquisitely sarcastic and irresistibly humorous:

"By the way, Mr. Speaker," said Mr. Lincoln, "do you know I am a military hero? Yes, sir, in the days of the Black Hawk War [1832], I fought, bled, and came away. Speaking of General Cass's career reminds me of my own. I was not at Stillman's Defeat, but I was about as near it as Cass to Hull's surrender, and like him, I saw the place very soon afterward. It is quite certain I did not break my sword, for I had none to break; but I bent my musket pretty badly on one occasion. If General Cass went in advance of me in picking whortleberries, I guess I surpassed him in charges upon the wild onions. If he saw any live, fighting Indians, it was more than I did, but I had a good many bloody struggles with the mosquitoes; and although I never fainted from loss of blood, I can truly say I was often very hungry."

|

| 23 Year Old, Illinois Militia, Captain Abraham Lincoln. Black Hawk War, 1832. |

[1] In the 1848 presidential campaign, Lewis Cass was the Democratic nominee but was defeated by the Whig candidate, Zachary Taylor.

When and Why the Democratic and Republican Parties Switched Platforms. President Lincoln's Philosophies were Actually Democratic.

|

| The Democratic-Republican Party was the earliest political party in the United States. |

|

| Democratic-Republican Party |

The Whig Party was a political party formed in 1834 by opponents of President Andrew Jackson and his Jacksonian Democrats, launching the 'two-party system.' Led by Henry Clay, the name "Whigs" was derived from the English antimonarchist party and was an attempt to portray President Jackson as "King Andrew." Whigs tended to be wealthy and had an aristocratic background. Most Whigs were based in New England and in New York. While Jacksonian Democrats painted the Whigs as the party of the aristocracy, they managed to win support from diverse economic groups and elect two presidents: William Henry Harrison and Zachary Taylor. The other two Whig presidents, John Tyler and Millard Fillmore, gained office as Vice Presidents next in the line of succession.

|

| Early Whig Party Campaign Poster. |

Northern Democrats were in serious opposition to Southern Democrats on the issue of slavery. Northern Democrats, led by Stephen Douglas, believed in Popular Sovereignty—letting the people of the territories vote on slavery. The Southern Democrats (known as "Dixiecrats"), reflecting the views of the late John C. Calhoun, insisted slavery was national.

The Democrats controlled the national government from 1852 until 1860, and Presidents Pierce and Buchanan were friendly to Southern interests. In the North, the newly formed anti-slavery Republican Party came to power and dominated the electoral college. In the 1860 presidential election, the Republicans nominated Abraham Lincoln. Still, the divide among Democrats led to the nomination of two candidates: John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky represented Southern Democrats, and Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois represented Northern Democrats. Nevertheless, the Republicans had a majority of the electoral vote regardless of how the opposition split or joined together, and Abraham Lincoln was elected.

WHY DID THE DEMOCRATIC AND REPUBLICAN PARTIES SWITCH PHILOSOPHIESThe National Union Party (1864–1865), the temporary name used by the Republican Party, was created by the merger of the Republican Party, Unionist Party, and War Democrats.

Fast forward to 1936. Democratic president Franklin Roosevelt won reelection that year on the strength of the New Deal, a set of Depression-remedying reforms including regulation of financial institutions, the founding of welfare and pension programs, infrastructure development, and more. Roosevelt won in a landslide against Republican Alf Landon, who opposed these exercises of federal power.

So, sometime between the late 1860s and 1936, the Democratic party of small government became the party of big government, and the Republican party of big government became rhetorically committed to curbing federal power. How did this switch happen?

|

| William Jennings Bryan Legendary "Octopus Poster" from the 1900 Campaign. |

Republicans didn't immediately adopt the opposite position of favoring limited government. Instead, for a couple of decades, both parties have promised an augmented federal government devoted in various ways to the cause of social justice. Only gradually did Republican rhetoric drift to the counterarguments. The party's small-government platform was cemented in the 1930s with its heated opposition to the New Deal.

But why did William Jennings Bryan and other turn-of-the-century Democrats start advocating for big government? Democrats, like Republicans, were trying to win the West. The admission of new western states to the union in the post-Civil War era created a new voting bloc, and both parties vied for its attention.

Democrats seized upon a way of ingratiating themselves to western voters: Republican federal expansions in the 1860s and 1870s had turned out favorable to big businesses based in the northeast, such as banks, railroads, and manufacturers, while small-time farmers like those who had gone west received very little. Both parties tried to exploit the discontent generated by promising the little guy some of the federal largesse that had already gone to the business sector. From then on, Democrats stuck with this stance — favoring federally funded social programs and benefits — while Republicans were gradually driven to the counterposition of hands-off government.

From a business perspective, the loyalties of the parties did not really switch. Although the rhetoric and, to a degree, the policies of the parties do switch places, their core supporters don't — which is to say, the Republicans remain, throughout, the party of bigger businesses; it's just that in the earlier era bigger companies want bigger government and in the later era they don't.

In other words, earlier on, businesses needed things that only a bigger government could provide, such as infrastructure development, a currency, and tariffs. Once these things were in place, a small, hands-off government became better for business.

|

| Abraham Lincoln, photograph by Gardner, 1865. |

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Sunday, August 16, 2020

Unfounded Quotes Attributed to Abraham Lincoln.

|

| CLICK |

Saturday, August 15, 2020

Alexander Gardner's Finest 1863 Photograph of President Lincoln.

“Alone” in the White House, the President decided on Sunday, August 9th to pay a visit to the famed Civil War photographer Alexander Gardner, whose studio was located at the corner of 7th and D streets. Earlier that year Mr. Gardner had left the employ of Matthew Brady, who was considered one of the premier photographers in the country, to open his own photography studio.

|

| Signed carte-de-visite of Lincoln, as photographed by Alexander Gardner in 1863. |

“Four Score and Seven” Magazine Article

Edited by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

German Journalist, Henry Villard, and Abraham Lincoln's Relationship with Him.

|

| Henry Villard 13 Years Old |

|

| The failed German Revolutions of 1848-1849 led to a large exodus of refugees. |

|

| Immigrants arriving in New York in the 1850s typically disembarked at South Street. |

WHEN ABRAHAM LINCOLN AND STEPHEN DOUGLAS DEBATED HENRY VILLARD WAS THERE TO REPORT TO THE GERMAN COMMUNITY.

|

| There were seven debates between Abe Lincoln and Stephen Douglas in the race for the Senate seat from Illinois. |

When he saw the previously unknown Lincoln for the first time, Villard thought that by his appearance “there was nothing in favor of Lincoln.” Lincoln was a “lean, lank, indescribably gawky figure, [with] an odd-featured, wrinkled, inexpressive, and altogether uncomely face,” he wrote. The urbane Villard remarked that when speaking, Lincoln “used singularly awkward, almost absurd up-and-down and sidewise movements of his body to give emphasis to his arguments.” Villard remembered later that Lincoln’s “voice was naturally good,” but Lincoln “frequently raised it to an unnatural pitch.”

These deficits of physical presentation would be serious impediments in a campaign that hinged on a series of debates between Lincoln and Douglas on slavery and the future of the country. Lincoln stood against the spread of slavery beyond those states where it already existed. Douglas argued that each new state admitted to the Union should be permitted to decide for itself whether it would be slave or free, whether blacks were people or property.

|

| Lincoln followed Douglas from town to town in Illinois, challenging him at every stop to debate him. The better-known Douglas finally agreed to seven public debates. |

Villard met Lincoln at Freeport and would meet him “frequently afterward in the course of the campaign.” While put-off by Lincoln’s rural style, Villard wrote that Lincoln was “most approachable, good-natured, and full of wit and humor.” Some of Lincoln’s “humor” gave Villard doubts about the Illinois lawyer. “I could not take a real personal liking to the man,” Villard says, “owing to an inborn weakness for which he was even then notorious and so remained during his great public career. He was inordinately fond of jokes, anecdotes, and stories.”

|

| Huge crowds turned out for the debates. Held in the summer and fall of 1858, each debate opened with a one-hour argument from one candidate, followed by a ninety-minute response from the other. Then the first speaker would have another thirty minutes to reply. Unlike modern presidential “debates” there were no questions from journalists, although audiences frequently yelled questions, comments, and insults to Lincoln and Douglas. |

|

| Henry Villard, 1866 |

While Villard was traveling the countryside, he wrote later, Lincoln “and I met accidentally, about nine o’clock on a hot, sultry evening, at a flag railroad station about twenty miles west of Springfield.” Lincoln “had been driven to the station in a buggy and left there alone. I was already there. The train that we intended to take for Springfield was about due. After vainly waiting for half an hour for its arrival, a thunderstorm compelled us to take refuge in an empty freight car standing on a side track, there being no buildings of any sort at the station.”

Two refugees from the weather, Lincoln, and Villard had a frank discussion. Here is how Villard recalled their conversation:

“We squatted down on the floor of the car and fell to talking on all sorts of subjects. It was then and there he told me that, when he was clerking in a country store, his highest political ambition was to be a member of the state Legislature. ‘Since then, of course,’ he said laughingly, ‘I have grown some, but my friends got me into THIS business [meaning the canvass]. I did not consider myself qualified for the United States Senate, and it took me a long time to persuade myself that I was. Now, to be sure,’ he continued, with another of his peculiar laughs, ‘I am convinced that I am good enough for it; but, in spite of it all, I am saying to myself every day: “It is too big a thing for you; you will never get it.” Mary [his wife] insists, however, that I am going to be Senator and President of the United States, too.’ These last words he followed with a roar of laughter, with his arms around his knees, and shaking all over with mirth at his wife’s ambition. ‘Just think,’ he exclaimed, ‘of such a sucker as me as President!’”Lincoln would, of course, be elected president just two years later and Henry Villard would develop a close journalistic relationship with him. Villard, who had arrived penniless in the United States in 1853, would one day own both The New York Post and the Nation Magazine, and a good deal more besides. These are stories we will develop in the next installment of The Immigrants’ Civil War.

GERMAN IMMIGRANT HENRY VILLARD WAS BECOMING ONE OF THE MOST PROMINENT JOURNALISTS IN CIVIL WAR ERA AMERICA.

|

| Lincoln's Farewell Address to Springfield, Illinois. |

|

| Lincoln Outside his Springfield House October of 1860. Illustration by Rees Print & Lithograph Company. |

Villard remembered Lincoln as a careful listener at these public receptions. The journalist wrote that when he met with visitors, Lincoln “showed remarkable tact in dealing with each of them, whether they were rough-looking Sangamon County farmers still addressing him familiarly as “Abe,” sleek and pert commercial travelers, staid merchants, sharp politicians; or preachers, lawyers, or other professional men.” Lincoln “showed a very quick and shrewd perception of and adaptation to individual characteristics and peculiarities. He never evaded a proper question or failed to give a fit answer,” according to Villard.

In February 1861, Lincoln began his long trip to Washington. The trip would take weeks. Lincoln planned on stopping at cities throughout the North along the way to build support for his presidency and opposition to Southern secession. Henry Villard had become close to Lincoln in his months of covering the Springfield interregnum and he was the only journalist allowed to accompany the president-elect as part of his official party. Villard wrote that “The start on the memorable journey was made shortly after eight o’clock on the morning of Monday, February 11. It was a clear, crisp winter day. Only about one hundred people, mostly personal friends, were assembled at the station to shake hands for the last time with their distinguished townsman. It was not strange that he yielded to the sad feelings which must have moved him at the thought of what lay behind and what was before him, and gave them utterance in a pathetic formal farewell to the gathering crowd…”

|

| Photo of Lincoln’s inauguration on March 4, 1861. With Civil War just weeks away, Lincoln concluded his Inaugural Address: “The mystic chords of memory, stretching from every battlefield and patriot grave to every living heart and hearthstone all over this broad land, will yet swell the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature.” |

“My Friends,– No one not in my position can appreciate the sadness I feel at this parting. To these people, I owe all that I am. Here I have lived more than a quarter of a century; here my children were born, and here one of them lies buried. I know not how soon I shall see you again. A duty devolves upon me which is, perhaps, greater than that which has devolved upon any other man since the days of Washington. He never would have succeeded except for the aid of Divine Providence, upon which he at all times relied. I feel that I cannot succeed without the same Divine aid which sustained him, and in the same Almighty Being I place my reliance for support; and I hope you, my friends, will all pray that I may receive that Divine assistance, without which I cannot succeed, but with which success is certain. Again I bid you all an affectionate farewell.”Along the way, Lincoln’s train stopped at every major city and town. There the president-elect would speak and local officials would offer their support. At some stops, local Republicans would hold “serenades, torchlight processions, and gala theatrical performances,” according to Villard. In one week alone, Lincoln gave more than fifty speeches at train stations and city halls. This campaign by train “was a very great strain upon his physical and mental strength, and he was well-nigh worn out when he reached Buffalo” wrote Villard.

|

| This photo of Lincoln was taken during President-elect Lincoln's first sitting in Washington, D.C., the day after his arrival by train, on February 24, 1861. It was taken by Scottish immigrant Alexander Gardner. The immigrant photographer would go on to record iconic images of the Civil War. |

When Lincoln reached New York City on February 20th, he was aware that the city’s mayor was sympathetic to the South. Mayor Fernando Wood hoped that if the slave states proceeded to leave the Union that the Federal government would let them go without military conflict. Lincoln met with Wood and the city council at City Hall and told them that “there is nothing that can ever bring me willingly to consent to the destruction of this Union.” He was prepared to wage war against anyone who tried to break up the United States.

|

| When Lincoln reached Pennsylvania he received word that there was a plot to assassinate him in Baltimore. Instead of traveling with his inaugural party, he disguised himself and traveled with just one bodyguard making a secret night trip through Baltimore on February 23, 1861, on his way to the national capital for his inauguration. The cartoonist had a field day with his supposed disguise in a Scottish Kilt and Tam. |

Edited by Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Friday, August 14, 2020

Abraham Lincoln's Funeral Rail-Car Landed in Minnesota in 1911 Before Being Destroyed by Fire.

That grass fire on March 18, 1911, not only consumed 10 blocks of early Columbia Heights, it razed the funeral train car that had carried slain President Abraham Lincoln’s body home from Washington, D.C., to Illinois. More than 7 million people in 180 cities and seven states had solemnly watched the train chug halfway across the country in 1865.

First, some background on what historians describe as the Air Force One of its era. The special car christened the “United States,” was built in Alexandria, Virginia, in 1863 and 1864 at the U.S. Military Car Shops during the Civil War.

It was designed with 16 wheels to smooth out the ride for Lincoln and his advisers. Etched-glass windows, fancy upholstered interior walls, and a painted bald eagle national crest adorned the car, which had meeting rooms and parlors for relaxing.

|

| Coach Recreation from the 150th Anniversary of Lincoln's Assassination, in Springfield, Illinois, on April 15, 2015. |

Newspapers published the funeral train’s scheduled stops in the days leading up to Lincoln’s May 4, 1865, funeral in Springfield, Illinois. Puffing black smoke, the train would stop in town after town along its 1,600-mile route. His coffin would be placed behind an elaborate horse-drawn hearse and brought to public buildings for viewing.

After the funeral, the government sold Lincoln’s rail-car for $6,850 ($115,960 today) to the Union Pacific Railroad, whose executives used it for several years. They sold it for $2,000 to an entrepreneur named Franklyn Snow, who tried to cash in on the morbid artifact at commercial exhibits across the Midwest. Maybe it was too close to the Civil War because the shows flopped.

The Colorado Central Railroad bought the car for $3,000 and stripped it down for use as a day coach and a work car. After bouncing around for nearly 40 years, the car found its would-be savior in Minnesota.

His name was Thomas Lowry, a Minneapolis land developer, railroad honcho, civic booster, and streetcar magnate. Realizing the value of this neglected piece of history, Lowry purchased the car in 1905. He planned to completely restore and permanently display it somewhere people could witness the old train car’s historic splendor.

Lowry called his treasure “the most sacred relic in the United States.” But he died in 1909 from tuberculosis that had dogged him for the four years he owned the car. Perhaps he hoped his rescue of the Lincoln funeral car might become part of his legacy, right along with his beloved namesake — the Lowry Hill neighborhood of Minneapolis.

After his death, Lowry’s estate donated the train car to the Minnesota Federation of Women’s Clubs. That group planned to secure it in an exhibit space later that summer of 1911. In the meantime, it was idled and stored in Columbia Heights on 37th Avenue between Quincy and Jackson streets.

Columbia Heights, located just north of Minneapolis, was an unlucky 13 years old when the grass fires swept across Anoka County that mid-March Saturday in 1911. The fire department was just four years old, paying local men a couple of bucks to respond when the bell rang above the original headquarters on 40th Avenue and 7th Street. By the time the fire squad responded, it was too late to save the old funeral rail-car.

“Car That Carried Remains of Lincoln Is Burned in Spectacular Prairie Fire,” screamed the headlines in the Minneapolis Sunday Journal. “Relic of Martyred President Reduced to Blackened Framework of Wood and Iron.”

Historians reported that they could only save a metal coupling from the ashes. Photos after the fire showed the charred shell and framework.

Over the years, pieces of the train car have surfaced. In St Paul, renowned painter and illustrator Edward Brewer moved the old Meeker Dam lock master’s house a half-mile up from the Mississippi River to Pelham Boulevard. The artist’s father had acquired a piece of the metal rail from the Lincoln funeral car, and Brewer used it to suspend a kettle over his fireplace, according to old newspaper clippings.

Illinois history buffs, meanwhile, have constructed a replica of the funeral car that now tours the country in a semitrailer truck, because driving it down rail lines proved too costly.

During that 2013 replica project, organizers didn’t know the precise color to paint the window frames. Witnesses couldn’t agree if it was claret red or chocolate brown.

So they tracked down a Minnesota man who inherited a window frame from a relative who had secured it after the 1911 fire. The man with the window agreed to scrape off a paint sample in exchange for a piece of black bunting that once had been draped on the funeral car. He requested that his name be kept secret. Paint-chip tests showed that the window frames were dark maroon with four parts black to one part red.

The mystery of the exterior color of President Lincoln's funeral train car... Solved!

Here is one more eerie coincidence. The real, one-of-a-kind, Lincoln hearse, which carried the president’s body from the Springfield train station to the Illinois Capitol building and then to the Oak Ridge Cemetery, is long gone. The livery’s owners had lent it out for the funeral procession and kept it for 22 years until it was destroyed in an 1887 fire. Also lost were three men and 200 horses.

|

| Funeral Hearse Recreation from the 150th Anniversary of Lincoln's Assassination, in Springfield, Illinois, on April 15, 2015. |

|

| One of two Surviving Silver Medallions from the Funeral Hearse's Center Side Panels. |

Compiled by Neil Gale, Ph.D.