In historical writing and analysis, PRESENTISM introduces present-day ideas and perspectives into depictions or interpretations of the past. Presentism is a form of cultural bias that creates a distorted understanding of the subject matter. Reading modern notions of morality into the past is committing the error of presentism. Historical accounts are written by people and can be slanted, so I try my hardest to present fact-based and well-researched articles.

Facts don't require one's approval or acceptance.

I present [PG-13] articles without regard to race, color, political party, or religious beliefs, including Atheism, national origin, citizenship status, gender, LGBTQ+ status, disability, military status, or educational level. What I present are facts — NOT Alternative Facts — about the subject. You won't find articles or readers' comments that spread rumors, lies, hateful statements, and people instigating arguments or fights.

FOR HISTORICAL CLARITY

When I write about the INDIGENOUS PEOPLE, I follow this historical terminology:

- The use of old commonly used terms, disrespectful today, i.e., REDMAN or REDMEN, SAVAGES, and HALF-BREED are explained in this article.

Writing about AFRICAN-AMERICAN history, I follow these race terms:

- "NEGRO" was the term used until the mid-1960s.

- "BLACK" started being used in the mid-1960s.

- "AFRICAN-AMERICAN" [Afro-American] began usage in the late 1980s.

— PLEASE PRACTICE HISTORICISM —

THE INTERPRETATION OF THE PAST IN ITS OWN CONTEXT.

EARLY WOOD RIVER SETTLERS

Thomas Rattan came from Ohio in 1804 to section 13 of Wood River Township, giving the name "Rattan's Prairie" to that neighborhood. He was one of, if not the first, to settle in this area of the Indiana Territory, named after 1800 until 1809 when the area was then in the Illinois Territory.

A pioneer named Tolliver Wright, from Virginia came to the western part of this township and settled near the mouth of Wood River in 1806 with his family. They later moved to the settlement between the forks of Wood River. Wright served as a captain in the Rangers in 1812. The Davidson brothers, natives of North Carolina, settled in 1806 near the Wanda comer. These men were the first settlers in the area.

In 1808, Abel, George, and William Moore came with their father, John, as far as Ford's Ferry on the Ohio River, where they separated from Abel and went on to Boone's Lick, Missouri.

Abel Moore was one of the pioneer settlers of Illinois in 1808, located in Madison County in the early days of its development. He and his family had come from North Carolina and had made arrangements to join an expedition organized in Kentucky to find a town in Missouri. The project was fostered by Daniel Boone, and the new town was to be called Boonville. Abel Moore and his family, on their way to join this colony, stopped in Illinois at a point opposite the mouth of the Missouri River, which had been agreed upon as a meeting place with others who were to join them, but after waiting for several months and vainly looking for his friends, Mr. Moore decided that he would locate in Madison County. Illinois was then a territory, and the government still possessed much of its land. Mr. Moore secured a claim between the forks of Wood River and developed a farm. He took an active and helpful part in the work of early improvement and progress there, and his name is indelibly inscribed on the pages of the pioneer history of Madison County.

After their father, John, died in 1809, the Moore brothers and their families came across the Mississippi River to Illinois and settled near their brother Abel in section 10. George and William were gunsmiths, and they manufactured rifle guns. One of them established a crude powder mill. They lived at the fork of Wood River. Philip Creamer manufactured locks and stocked guns. He was an expert workman who lived in the area. Other smiths manufactured plows, hoes, axes, mattocks, and other articles made of iron, as called for. It is a marvelous evolution that now the Equitable Powder Company and the Western Cartridge Company, two of the largest industries of their kind in the West, are located just two miles lower down on the banks of Wood River.

The settlements on Wood River were made, many of them, before the Altons attracted much notice. The Moore brothers, Abel, George, and William, each built a brick house for a residence, which probably was the first of that material used in that portion of the county.

One of the first grain mills in the area was a "hand" mill (wheels working together by the friction of rawhide instead of cogs), belonging to John Finley for grinding com. It was near the present site of Bethalto.

George Moore had a band mill on his farm two miles east of Upper Alton at an early date, which he had brought out from Kentucky. The map coordinates are the northwest quarter of section 10 T5N/R9W. Abel Moore operated his brother George's early grist mill. People came in their ox-carts from miles away in order to have their corn ground.

William Jones, a Virginian and a Baptist minister was a county resident as early as 1806 and was the head of a large family, many of the descendants being now scattered over the county. He was a member of the territorial and state legislature and captain of a company of rangers in 1813. He settled on the sandridge in Wood River Township and soon afterward moved to Fort Russell Township.

Rachel Thomas, Reason Reagan's wife, and Mary "Polly" Thomas, William Moore's wife, were sisters. They also had a brother named Samuel Thomas. Rachel married Reason Reagan on February 3, 1808, in Livingston County, Kentucky, and they moved to the Wood River area in 1810. It is unknown whether the Reagan family moved from Kentucky to Missouri and then back to Illinois, but it appears likely based on family ties.

Mary "Polly" Thomas Moore, sister of Rachel Thomas Reagan, was born May 9, 1788, in Pendleton, Anderson County, North Carolina, and was married December 15, 1803, in Pendleton Dist., South Carolina, to William Moore.

FAMILY GROUP'S BIRTHS AND DEATH

JOHN MOORE (father of Abel, George, and William)

Born: Approximately 1757 - Place: Surry, NC

Died: 1808 - Place: Boone's Lick, MO

NANCY ROBERTS (mother of Able, George, and William)

Born: Approximately 1761 - Place: Surry, NC

Died: 1808 - Place: Boone's Lick, MO

NANCY MOORE

Born: Approximately 1776 - Place: Surry, NC

Died: Before 1814 - Place: Somewhere in Illinois

Married: April 8, 1794, to James Beeman - Place: Surry, NC

ABEL MOORE

Born: January 3, 1783 - Place: Surry, NC

Died: February 10, 1846 - Place: Wood River, Madison, IL

Buried: ? - Place: Wood River, Madison, IL

GEORGE MOORE

Born: Approximately 1784 - Place: Surry, NC

WILLIAM MOORE

Born: September 11, 1785 - Place: NC

Died: February 15, 1834 - Place: Adams, IL

Married: December 15, 1803 - Place: Pendleton Dist., SC

MARY "POLLY" THOMAS (wife of William Moore)

Born: May 9, 1788 - Place: Pendleton, Anderson County, SC

Died: April 24, 1871 - Place: Dripping Springs, Hays, TX

Buried: ? - Place: Moore Cemetery, Dripping Springs, Hays, TX

Married: December 15, 1803 - Place: Pendleton Dist., SC

Father: Irwin Thomas

Mother: Elizabeth Hubbard Thomas

THE SIX CHILDREN BORN TO WILLIAM AND POLLY MOORE, BEFORE THE MASSACRE

1) JOHN MOORE

Born: 1804 - Place: Pendleton, Anderson County, SC

Died: July 10, 1814 - Place: Wood River, Madison County, IL

2) ABEL MOORE

Born: August 6, 1806 - Place: Livingston, KY

Died: August 6, 1806 - Place: Livingston, KY

3) GEORGE MOORE

Born: 1807 - Place: Livingston, KY

Died: July 10, 1814 - Place: Wood River, Madison County, IL

4) RACHEL MOORE

Born: October 5, 1808 - Place: Livingston, KY

Died: January 28, 1853 - Place: ?

5) ELIZABETH MOORE

Born: July 16, 1811 - Place: St. Clair, IL

Died: September 12, 1812 - Place: Wood River, Madison County, IL (Age 14 months)

6) JAMES MOORE

Born: July 22, 1813 - Place: Wood River, Madison County, IL

Died: July 22, 1813 - Place: Wood River, Madison County, IL

THE REAGAN FAMILY

RACHEL THOMAS (wife of Reason Reagan)

Born: 1790 - Place: Pendleton, Anderson County, SC

Died: July 10, 1814 - Place: Madison, IL

Married: February 3, 1808 - Place: Livingston County, Kentucky

ELIZABETH REAGAN (daughter of Reason and Rachel)

Died: July 10, 1814 - Place: Madison, IL (Age 7)

TIMOTHY REAGAN (son of Reason and Rachel)

Died: July 10, 1814 - Place: Madison, IL (Age 3)

UNBORN REAGAN CHILD Died: July 10, 1814

THE INDIANS AND THE WAR OF 1812

Although there were frequent tensions, only a few of the whites who began settling in the area around 1800 were killed by the Indians, whom they steadily displaced as they settled in and claimed, cleared, and fenced the land.

In the beginning, Indians were still roaming over this portion of the state, and a man who was cultivating a small farm close to where the glassworks company would be built (Alton, Illinois), was killed in 1811 by Indians.

Ellen Nore, an associate professor at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville and authority on local history, said, "The Kickapoo Indians, who had been in Illinois since the early 18th century, were being driven out by the American settlers. It was really a matter of people struggling against conquest." Indeed, the "Wood River Massacre" victims may have been casualties of war rather than a random act of violence. At the time, the United States and Great Britain were engaged in what we now call the War of 1812. Several Midwestern Indian tribes were allies of the British, who paid bounties for American scalps. She said the Kickapoos aligned themselves with the British in hopes of benefiting from a British victory. "Massacre" was a term applied to the incident by white historians, according to Nore.

"This was not an isolated Indian attack," said Alton Township Supervisor Don Huber, a local historian, "it was part of the War of 1812."

Thomas Rattan came from Ohio in 1804 to section 13 of Wood River Township, giving the name "Rattan's Prairie" to that neighborhood. He was one of, if not the first, to settle in this area of the Indiana Territory, named after 1800 until 1809 when the area was then in the Illinois Territory.

A pioneer named Tolliver Wright, from Virginia came to the western part of this township and settled near the mouth of Wood River in 1806 with his family. They later moved to the settlement between the forks of Wood River. Wright served as a captain in the Rangers in 1812. The Davidson brothers, natives of North Carolina, settled in 1806 near the Wanda comer. These men were the first settlers in the area.

In 1808, Abel, George, and William Moore came with their father, John, as far as Ford's Ferry on the Ohio River, where they separated from Abel and went on to Boone's Lick, Missouri.

Abel Moore was one of the pioneer settlers of Illinois in 1808, located in Madison County in the early days of its development. He and his family had come from North Carolina and had made arrangements to join an expedition organized in Kentucky to find a town in Missouri. The project was fostered by Daniel Boone, and the new town was to be called Boonville. Abel Moore and his family, on their way to join this colony, stopped in Illinois at a point opposite the mouth of the Missouri River, which had been agreed upon as a meeting place with others who were to join them, but after waiting for several months and vainly looking for his friends, Mr. Moore decided that he would locate in Madison County. Illinois was then a territory, and the government still possessed much of its land. Mr. Moore secured a claim between the forks of Wood River and developed a farm. He took an active and helpful part in the work of early improvement and progress there, and his name is indelibly inscribed on the pages of the pioneer history of Madison County.

After their father, John, died in 1809, the Moore brothers and their families came across the Mississippi River to Illinois and settled near their brother Abel in section 10. George and William were gunsmiths, and they manufactured rifle guns. One of them established a crude powder mill. They lived at the fork of Wood River. Philip Creamer manufactured locks and stocked guns. He was an expert workman who lived in the area. Other smiths manufactured plows, hoes, axes, mattocks, and other articles made of iron, as called for. It is a marvelous evolution that now the Equitable Powder Company and the Western Cartridge Company, two of the largest industries of their kind in the West, are located just two miles lower down on the banks of Wood River.

The settlements on Wood River were made, many of them, before the Altons attracted much notice. The Moore brothers, Abel, George, and William, each built a brick house for a residence, which probably was the first of that material used in that portion of the county.

One of the first grain mills in the area was a "hand" mill (wheels working together by the friction of rawhide instead of cogs), belonging to John Finley for grinding com. It was near the present site of Bethalto.

George Moore had a band mill on his farm two miles east of Upper Alton at an early date, which he had brought out from Kentucky. The map coordinates are the northwest quarter of section 10 T5N/R9W. Abel Moore operated his brother George's early grist mill. People came in their ox-carts from miles away in order to have their corn ground.

William Jones, a Virginian and a Baptist minister was a county resident as early as 1806 and was the head of a large family, many of the descendants being now scattered over the county. He was a member of the territorial and state legislature and captain of a company of rangers in 1813. He settled on the sandridge in Wood River Township and soon afterward moved to Fort Russell Township.

Rachel Thomas, Reason Reagan's wife, and Mary "Polly" Thomas, William Moore's wife, were sisters. They also had a brother named Samuel Thomas. Rachel married Reason Reagan on February 3, 1808, in Livingston County, Kentucky, and they moved to the Wood River area in 1810. It is unknown whether the Reagan family moved from Kentucky to Missouri and then back to Illinois, but it appears likely based on family ties.

Mary "Polly" Thomas Moore, sister of Rachel Thomas Reagan, was born May 9, 1788, in Pendleton, Anderson County, North Carolina, and was married December 15, 1803, in Pendleton Dist., South Carolina, to William Moore.

FAMILY GROUP'S BIRTHS AND DEATH

JOHN MOORE (father of Abel, George, and William)

Born: Approximately 1757 - Place: Surry, NC

Died: 1808 - Place: Boone's Lick, MO

NANCY ROBERTS (mother of Able, George, and William)

Born: Approximately 1761 - Place: Surry, NC

Died: 1808 - Place: Boone's Lick, MO

NANCY MOORE

Born: Approximately 1776 - Place: Surry, NC

Died: Before 1814 - Place: Somewhere in Illinois

Married: April 8, 1794, to James Beeman - Place: Surry, NC

ABEL MOORE

Born: January 3, 1783 - Place: Surry, NC

Died: February 10, 1846 - Place: Wood River, Madison, IL

Buried: ? - Place: Wood River, Madison, IL

GEORGE MOORE

Born: Approximately 1784 - Place: Surry, NC

WILLIAM MOORE

Born: September 11, 1785 - Place: NC

Died: February 15, 1834 - Place: Adams, IL

Married: December 15, 1803 - Place: Pendleton Dist., SC

MARY "POLLY" THOMAS (wife of William Moore)

Born: May 9, 1788 - Place: Pendleton, Anderson County, SC

Died: April 24, 1871 - Place: Dripping Springs, Hays, TX

Buried: ? - Place: Moore Cemetery, Dripping Springs, Hays, TX

Married: December 15, 1803 - Place: Pendleton Dist., SC

Father: Irwin Thomas

Mother: Elizabeth Hubbard Thomas

THE SIX CHILDREN BORN TO WILLIAM AND POLLY MOORE, BEFORE THE MASSACRE

1) JOHN MOORE

Born: 1804 - Place: Pendleton, Anderson County, SC

Died: July 10, 1814 - Place: Wood River, Madison County, IL

2) ABEL MOORE

Born: August 6, 1806 - Place: Livingston, KY

Died: August 6, 1806 - Place: Livingston, KY

3) GEORGE MOORE

Born: 1807 - Place: Livingston, KY

Died: July 10, 1814 - Place: Wood River, Madison County, IL

4) RACHEL MOORE

Born: October 5, 1808 - Place: Livingston, KY

Died: January 28, 1853 - Place: ?

5) ELIZABETH MOORE

Born: July 16, 1811 - Place: St. Clair, IL

Died: September 12, 1812 - Place: Wood River, Madison County, IL (Age 14 months)

6) JAMES MOORE

Born: July 22, 1813 - Place: Wood River, Madison County, IL

Died: July 22, 1813 - Place: Wood River, Madison County, IL

THE REAGAN FAMILY

RACHEL THOMAS (wife of Reason Reagan)

Born: 1790 - Place: Pendleton, Anderson County, SC

Died: July 10, 1814 - Place: Madison, IL

Married: February 3, 1808 - Place: Livingston County, Kentucky

ELIZABETH REAGAN (daughter of Reason and Rachel)

Died: July 10, 1814 - Place: Madison, IL (Age 7)

TIMOTHY REAGAN (son of Reason and Rachel)

Died: July 10, 1814 - Place: Madison, IL (Age 3)

UNBORN REAGAN CHILD Died: July 10, 1814

THE INDIANS AND THE WAR OF 1812

Although there were frequent tensions, only a few of the whites who began settling in the area around 1800 were killed by the Indians, whom they steadily displaced as they settled in and claimed, cleared, and fenced the land.

In the beginning, Indians were still roaming over this portion of the state, and a man who was cultivating a small farm close to where the glassworks company would be built (Alton, Illinois), was killed in 1811 by Indians.

Ellen Nore, an associate professor at Southern Illinois University Edwardsville and authority on local history, said, "The Kickapoo Indians, who had been in Illinois since the early 18th century, were being driven out by the American settlers. It was really a matter of people struggling against conquest." Indeed, the "Wood River Massacre" victims may have been casualties of war rather than a random act of violence. At the time, the United States and Great Britain were engaged in what we now call the War of 1812. Several Midwestern Indian tribes were allies of the British, who paid bounties for American scalps. She said the Kickapoos aligned themselves with the British in hopes of benefiting from a British victory. "Massacre" was a term applied to the incident by white historians, according to Nore.

"This was not an isolated Indian attack," said Alton Township Supervisor Don Huber, a local historian, "it was part of the War of 1812."

The war would end without a decisive victor, and the Kickapoos would eventually be driven west. The Potawatomi signed treaties in 1817, ending their opposition to the American settlement of Illinois. The Winnebago were moved westward with treaties after the War of 1812. The Sac (Sauk) and Meskwaki (Fox) finally left Illinois for the last time in 1832 at the end of the Black Hawk War.

SUNDAY MORNING AND AFTERNOON SOCIAL

July 10, 1814, was a Sunday, and it started out as a peaceful and pleasant day. The families in the area never knew the day would end in great tragedy. William Moore was on duty at Fort Butler near St. Jacob. Abel Moore had gone to Fort Russell for the day and was on duty there. Samuel Thomas, Rachel's brother, stated that he was accompanied by his sister, Catherine Reagan, who had recently come to the territory when they went to a church service which was probably held at the Baptist Church near Vaughn Cemetery.

That morning, they were probably accompanied partway by Rachel Reagan and her two children, who spent the day with her sister "Polly," Mrs. William Moore. As it was along the way, Polly and her children were there, as was Miss Hannah Bates (who was the sister of Abel Moore's wife). The time was spent peacefully while the women talked and the children played games. They were all going to Abel Moore's cabin for supper that night.

In the afternoon, all those present at William Moore's house, Polly Moore and her two sons and one daughter, Rachel Reagan and her son and daughter, and Hannah Bates went to Abel Moore's house to begin their preparation of the family group supper that they had planned for that evening. After arriving there, Rachel decided she would go home and pick some beans that would be added to their planned evening meal. Some of the children chose to go along with her. Altogether, Rachel's two children were Rachel's sons, William Moore's son and Abel Moore's son.

That was a total of seven, but they almost had eight. Hannah Bates decided to go along and visit a little more with them, but a short time later, Hannah returned to the Moore house. Some people thought she may have had a premonition that something terrible would happen. Others say her shoes did not fit well, and she was most uncomfortable. Whatever the reason, against the earnest entreaties of Mrs. Reagan, she retraced her steps to Moore's house, which was closer than Rachel's. It saved her life.

THE MASSACRE

Why were the Indians in the area? Had they been watching the families in the Moore settlement? The following information has been found in the 'Old Settlers of Green County' published in 1873. In the biography of Samuel Thomas, Reason Reagan's brother-in-law, it is stated that on July 8, 1814, two days before the massacre, Reason and Samuel had gone to a deerlick about ten miles west of the settlement and there encamped for the night. At the same time, it was later ascertained, that a company of eleven Indians had been three miles distant and the next morning found the abandoned camp of Thomas and Reagan. The Indians determined the group had been a small one and decided to follow them to their destination. This brought the Indians to the settlement.

Picture Rachel and Hannah, walking along talking, maybe about the day they were having to this point, or perhaps the task that was ahead of them, picking and cleaning the beans and returning to Abel's home. Rachel's two children were walking with her, and the four older boys were ahead of her, probably being boys and maybe throwing sticks and rocks and exploring as they made their way through the woods.

At the point where Hannah Bates turned back, she could not have been more than two or three hundred yards from where the dead body of Mrs. Reagan would be found. Mrs. Reagan and the six children were all tomahawked, scalped, and stripped of all their clothing. They remained all night on the ground where they were murdered.

Mrs. Reagan and her two children were killed nearest Capt. Abel Moore's place; the other children were found lying farther on, two at a place. One, the youngest child, Timothy Reagan, three years old, when found, was still alive. Timothy was found scalped and with a deep gash on each side of his face and so badly wounded that he could not live. The blood had clotted in the hair and staunched the wound. A messenger was sent for the nearest physician, who came and dressed the wounds of the little one. The doctor said that when the wound was washed, the child would bleed to death, and so it was. He did not survive the treatment.

In an interview with a St. Louis newspaper a few days after the massacre, Reason Reagan stated his wife, Rachel, had been with child, and he described her as being far advanced in pregnancy at the time of the massacre. This would raise the death total to eight.

The Indians may have reached the empty Reagan cabin first. Looking backward, they probably decided to follow the trail to the next site, whatever it might be. This put them on the trail towards Abel Moore's home as Rachel and the children approached from the other direction. Had the Indians arrived earlier, they probably would have attacked the Abel Moore home, where there would have been a much greater loss of life. If they were a little later, they would have found Rachel at home in the garden. Either way, the outcome would have been tragic.

Friday, July 8 - Reason Reagan and Samuel Thomas hunting at a site 10 miles from the settlement.

Saturday morning, July 9 - Reagan and Thomas return to the Reagan home.

Sunday morning, July 10 - Scouts from an Indian encampment find Reagan and Thomas' hunting site and elect the hunters' trail back to their destination, which turns out to be the Reagan cabin. There is no one home, so they follow the path and come upon Rachel Reagan and the six children.

THE GRUESOME DISCOVERY

William Moore, having returned that day to look after the women and children at home, from where he was on military duty at Fort Butler, near the present village of St. Jacobs, became alarmed as night approached and the children had not returned, and went in search of them, first going to his brother, Abel Moore's place to see if they were there. His wife, who was Mrs. Reagan's sister, also started on horseback to look for them, taking a different route from the one her husband took. His wife chose to go through the woods, and he walked along the wagon path. When Mrs. William Moore found the children lying by the road, she thought they had become tired and laid down to sleep. There was not sufficient light to tell the size or sex of the person, and she called over and over again the name of one and another of her children, supposing one of them to be asleep. She got down from her horse to pick up the youngest child, but just then, a crackling noise and flash of light from a burning hickory tree nearby alarmed her and, fearing Indians might be in ambush there, she grabbed the boy, Timothy, and sprang on her horse and reached home in advance of her husband. Although they did not meet until they both returned home, they both found the lifeless bodies in the darkness, lying by the wayside, and each placed a hand upon the bare shoulder of Mrs. Reagan.

The following has been taken from the '1882 Brink's History of Madison County': "What must have been her sensations as Mary 'Polly' Moore placed her hand upon the back of a naked corpse, and felt, on further examination, the quivering flesh from which the scalp had recently been torn? In the gloom of the night, she could indistinctly see the figure of the little child of Mrs. Reagan's sitting so near the body of its mother as to lean its head, first one side, then the other, on the insensible and mangled body, as she leaned over, the little one said - 'The black man raised his ax and cut them again.' She saw no further, but thrilled with horror and alarm, hastily remounted her frightened horse, and quickly hurried home where she heated water, intending by that means, to defend herself from the savage foe."

William Moore had not been long absent from his brother Abel before he returned, saying that someone had been killed by the Indians. He had discerned the body of a person lying on the ground, but whether wan or woman, it was too dark for him to see without a closer inspection than was deemed safe.

The habits of the Indians were too well known by these settlers to leave a man in Mr. Moore's situation free from the apprehension of an ambuscade still near. Thinking the Indians were having a general uprising, he wanted to warn the other people in the area and get them to safety.

From Abel's house, he took Abel's wife and her remaining children along with Hannah Bates; and they headed for William's house and his family, having no idea if his wife had returned from her search.

The first thought was to find refuge in the blockhouse. Mr. Moore desired his brother's family to go directly by the road to the blockhouse while he would pass by his own house and take his family to the fort with him. The night was dark, and the road passed through a heavy forest. Instead of going on alone without some protection, the women and children chose to accompany William Moore, though the distance to the Fort Wood River was thereby nearly doubled. The feelings of the party as they groped their way through the dark woods can be more easily imagined than described. Sorrow for the supposed loss of their relatives and children was mingled with horror at the manner of their death and fear for their own safety and pain at the dreadful idea that the remains of their dearest friends lay mangled on the cold ground near them while they were denied the privilege of seeing and preparing them for sepulture. Silently they passed on until they came to the home of William Moore, when he exclaimed, as if relieved from strained apprehension, "Thank God, Polly is not killed!" The horse which his wife had ridden was standing near the house. As they let down the bars and gained admission to the yard, his wife came running out, exclaiming, "They are killed by the Indians, I expect." The whole party then departed hastily for the blockhouse, to which place, all the neighbors, to whom warning had been communicated by signals, gathered by daybreak.

BURYING THE DEAD

At dawn, the scene of the tragedy was found, and the bodies of the children (scattered all along the path) indicated that they had tried to escape.

The sight of Rachel and the six children lying by the roadside, all stripped of clothing, must have been horrifying. The bodies all showed signs of being bludgeoned by tomahawk, and all seven were scalped.

The bodies were collected for burial. They were all buried with boards laid on the bottom and the sides and above the bodies. There were no men to make coffins. The graves were dug with coffin-shaped vaults at the bottom, which was lined with slabs split from trees nearby as nearly like planks as possible; and after the bodies were placed in the vaults, they were covered over with the same kind of split slabs.

The seven were buried in three graves; Mrs. Reagan and her two children, Elizabeth and Timothy, in one grave; Captain Moore's two children, William and Joel, in another, and William Moore's two children, John and George, in the third.

Mr. Solomon Pruitt, who was not in the pursuit, assisted in the burial of the victims. He hauled them on a small one-horse sled to the burying ground south of Bethalto. There were no wagons in those days. There, a stone slab marks their resting place.

The Vaughn cemetery, in section 24, where the victims of the Wood River massacre were buried, was the first regular place of interment in the area. It antedates the year 1809. Here the first Baptist church in the township was built. Rev. William Jones, eminent as a legislator as well as a minister, was the first preacher. His descendants, or some of them, still live in the county and are worthy of their distinguished ancestry.

In this primitive cemetery, the inscriptions on various tombstones can still be deciphered. Among others appear the names of members of the Ogle, Odell, and Rattan families.

The original sandstone marker with the inscription: "William & Joel Moore was killed by the Indians July 10, 1814" was taken from this cemetery many years ago but can now be seen at the Alton Museum of History & Art.

PURSUING THE PERPETRATORS

A young man named John Harris, living at Able Moore's home, was sent that night on horseback bearing the sad tidings to Fort Russell, located in the township of that name, Captain Samuel Whiteside (Whiteside County, Illinois was named for General Samuel Whiteside, an Illinois officer in the War of 1812 and Black Hawk War.) commanding, and to Fort Butler, Captain Moore commanding, to give the alarm. Leaving the latter place about one o'clock the same night, about seventy of the rangers from both forts, among whom were James and Solomon Preuitt, had arrived at Moore's Fort about sunrise and proceeded to the scene of the tragedy.

Seven were missing, and their bodies lay mangled and bleeding within a mile of the fort in the dark forest. There was little rest that night at the fort. The women and children of the neighborhood, with the few men who were not absent with the rangers, crowded together, not knowing but that at any minute, the Indians might begin their attack.

The news soon spread, and it was not long before Captain Whiteside, and nine others gave pursuit. Among them were James Pruitt, Abraham Pruitt, William and John Sample, James Starkden, William Montgomery, and Peter Waggoner, whose descendants still live in Wood River and Moro townships.

They were enabled to follow the track of the broken limbs on the bushes which the Indians did, as was supposed to tantalize the helpless women, thinking there were no men able enough to pursue them. Further on, by the way, they made through the tall prairie grass, and also by blood. The Indians, when they learned they were pursued, frequently bled themselves to facilitate their speed and give them greater endurance.

The weather was extremely hot, and some of the ranger's horses gave out entirely. Their order was to keep up the pursuit.

The rangers pressed upon the fleeing red men. It was on the evening of the second day between sunset and dark that they came in sight of the Indians at a small stream entering the Sangamon River on the dividing ridge, about seventy miles distant in Morgan County. This site was named Indian Creek to remember what had taken place there.

There stood on the ridge, at that time, a lone cottonwood tree. Several Indians climbed this tree to look back. They saw their pursuers from that tree. They separated and went in different directions, all making for the timber. When the whites came to the tree, they, too, divided and pursued the Indians separately.

James and Abraham Pruitt, taking the trail of an Indian, soon came in sight of him, and the former, having the fastest horse, soon came within range of him. He rode up to within thirty yards and shot him in the thigh. The Indian fell but managed to get to a fallen treetop. Abraham soon came up, and they concluded to ride in on the Indian and finish him, which Abraham did by shooting and killing him where he lay. In the Indian's shot-pouch was found the scalp of Mrs. Reagan. The Indian tried to raise his gun to shoot but was too weak to fire. The Indian had also lost his flint, or he might have killed one of his pursuers. His rifle is supposed to be in the Pruitt family yet. The place where the Indians were overtaken was near where Virden now stands. The remaining Indians hid in the timber and the drift of the creek. It was learned, afterward, at the treaty of Galena that only one Indian escaped, and that was the chief who led the party.

Where was Reason Reagan? Some new light has been shed on reason's whereabouts on the day of the massacre. Samuel Thomas, Rachel's brother, states that reason was accompanied by his younger sister, Cathy, when he went to church on Sunday morning. Cathy was a young single woman who had recently come to the area; and, if she were to visit with anyone after church, she would have to be accompanied. It was summertime on a Sunday with no evident reason for concern. Cathy would eventually marry David Carter, who lived in the area. She may have known him by this time, or perhaps she was visiting with others. This provides a likely scenario for Reason's Sunday away from the family. In that era, it was not unusual to be unaware of happenings just a few miles away. None of our research as of yet had revealed when reason returned home and learned of his family's fate.

THE SURVIVING FAMILIES, MOVING ON

"Of those who took refuge in the fort that night, there is probably but one now living, Mrs. Nancy Hedden, a daughter of Captain Abel Moore. She resides at San Diego, California and was then about a year and a half old," stated V. P. Richmond in 1882.

George Moore married Peggy McFarlin on December 27, 1814, in Madison County, Illinois. George Moore had two children: Margaret and Walter Moore, while living in Madison County, Illinois.

Years later, Mr. Thomas S. Pinckard, who at the time was a resident of Springfield, Illinois, had kindly sent the following: "I have a vivid recollection of several of the old settlers who were living when I was a boy. Abel Moore, in his Dearborn wagon, with his wooden leg..."

One of the members of the church, Mrs. Bates, the mother of the wife of Abel Moore, lived near Jersey Landing; another, Mrs. Askew, sister-in-law of Mrs. Abel Moore, also lived near Jersey Landing, and yet both came monthly, on horseback, exposed to imminent danger and yet with great regularity and delight, to attend the stated appointments of the church. Mrs. Askew was Hannah Bates Askew. She married Josiah Askew.

Another gallant officer of Wood River township was the son of Abel, Maj. Frank Moore, the famous Civil War cavalry raider and leader. It was said of him by a certain major general on one occasion: "Maj. Moore has captured more prisoners than my whole army corps."

In the sale of the old Abel Moore's homestead, the Moore children reserved this sacred spot where the cabin of Abel once stood as a lasting tribute to their departed parents. This is where the fenced gravesite in Gordon Moore Park can be seen today.

Abel Moore died in 1846 at the age of 63. Mary Moore died the day before her husband, aged 61. They lie side by side on the very spot of ground where their pioneer cabin was constructed.

Before the massacre, William's family consisted of his wife, daughter, and two sons, John and George, both of whom were victims at the Wood River massacre.

Six children were born to the family afterward. When they moved to Pike County, Illinois, in 1830, they took four children with them. Rachel had married five years earlier. Rachel, Lorenzo, Enoch, and Matthew lived to maturity and had families of their own. Louisa, aged 13, died in 1831 in Pike County.

George had no children when he came to Madison County, but two were born while residing there, Margaret and Walter. The family migrated to Independence, Missouri, in 1837.

A new monument was dedicated on September 24, 1980, in a more visible spot for public viewing. It is almost directly across the Highway 140 entrance to the Gordon Moore Alton Community Park. Gordon Moore was no relation to the other Moores; however, the park was built on the farm of the pioneer Abel and Mary Bates Moore. Abel Moore and Mary Bates Moore are buried where their house formerly stood, just a short distance from the new monument.

A new monument was dedicated on September 24, 1980, in a more visible spot for public viewing. It is almost directly across the Highway 140 entrance to the Gordon Moore Alton Community Park. Gordon Moore was no relation to the other Moores; however, the park was built on the farm of the pioneer Abel and Mary Bates Moore. Abel Moore and Mary Bates Moore are buried where their house formerly stood, just a short distance from the new monument.

Exclusive permission from author William Wilson.

Edited by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

SUNDAY MORNING AND AFTERNOON SOCIAL

July 10, 1814, was a Sunday, and it started out as a peaceful and pleasant day. The families in the area never knew the day would end in great tragedy. William Moore was on duty at Fort Butler near St. Jacob. Abel Moore had gone to Fort Russell for the day and was on duty there. Samuel Thomas, Rachel's brother, stated that he was accompanied by his sister, Catherine Reagan, who had recently come to the territory when they went to a church service which was probably held at the Baptist Church near Vaughn Cemetery.

That morning, they were probably accompanied partway by Rachel Reagan and her two children, who spent the day with her sister "Polly," Mrs. William Moore. As it was along the way, Polly and her children were there, as was Miss Hannah Bates (who was the sister of Abel Moore's wife). The time was spent peacefully while the women talked and the children played games. They were all going to Abel Moore's cabin for supper that night.

In the afternoon, all those present at William Moore's house, Polly Moore and her two sons and one daughter, Rachel Reagan and her son and daughter, and Hannah Bates went to Abel Moore's house to begin their preparation of the family group supper that they had planned for that evening. After arriving there, Rachel decided she would go home and pick some beans that would be added to their planned evening meal. Some of the children chose to go along with her. Altogether, Rachel's two children were Rachel's sons, William Moore's son and Abel Moore's son.

That was a total of seven, but they almost had eight. Hannah Bates decided to go along and visit a little more with them, but a short time later, Hannah returned to the Moore house. Some people thought she may have had a premonition that something terrible would happen. Others say her shoes did not fit well, and she was most uncomfortable. Whatever the reason, against the earnest entreaties of Mrs. Reagan, she retraced her steps to Moore's house, which was closer than Rachel's. It saved her life.

THE MASSACRE

Why were the Indians in the area? Had they been watching the families in the Moore settlement? The following information has been found in the 'Old Settlers of Green County' published in 1873. In the biography of Samuel Thomas, Reason Reagan's brother-in-law, it is stated that on July 8, 1814, two days before the massacre, Reason and Samuel had gone to a deerlick about ten miles west of the settlement and there encamped for the night. At the same time, it was later ascertained, that a company of eleven Indians had been three miles distant and the next morning found the abandoned camp of Thomas and Reagan. The Indians determined the group had been a small one and decided to follow them to their destination. This brought the Indians to the settlement.

Picture Rachel and Hannah, walking along talking, maybe about the day they were having to this point, or perhaps the task that was ahead of them, picking and cleaning the beans and returning to Abel's home. Rachel's two children were walking with her, and the four older boys were ahead of her, probably being boys and maybe throwing sticks and rocks and exploring as they made their way through the woods.

At the point where Hannah Bates turned back, she could not have been more than two or three hundred yards from where the dead body of Mrs. Reagan would be found. Mrs. Reagan and the six children were all tomahawked, scalped, and stripped of all their clothing. They remained all night on the ground where they were murdered.

Mrs. Reagan and her two children were killed nearest Capt. Abel Moore's place; the other children were found lying farther on, two at a place. One, the youngest child, Timothy Reagan, three years old, when found, was still alive. Timothy was found scalped and with a deep gash on each side of his face and so badly wounded that he could not live. The blood had clotted in the hair and staunched the wound. A messenger was sent for the nearest physician, who came and dressed the wounds of the little one. The doctor said that when the wound was washed, the child would bleed to death, and so it was. He did not survive the treatment.

In an interview with a St. Louis newspaper a few days after the massacre, Reason Reagan stated his wife, Rachel, had been with child, and he described her as being far advanced in pregnancy at the time of the massacre. This would raise the death total to eight.

The Indians may have reached the empty Reagan cabin first. Looking backward, they probably decided to follow the trail to the next site, whatever it might be. This put them on the trail towards Abel Moore's home as Rachel and the children approached from the other direction. Had the Indians arrived earlier, they probably would have attacked the Abel Moore home, where there would have been a much greater loss of life. If they were a little later, they would have found Rachel at home in the garden. Either way, the outcome would have been tragic.

Friday, July 8 - Reason Reagan and Samuel Thomas hunting at a site 10 miles from the settlement.

Saturday morning, July 9 - Reagan and Thomas return to the Reagan home.

Sunday morning, July 10 - Scouts from an Indian encampment find Reagan and Thomas' hunting site and elect the hunters' trail back to their destination, which turns out to be the Reagan cabin. There is no one home, so they follow the path and come upon Rachel Reagan and the six children.

THE GRUESOME DISCOVERY

William Moore, having returned that day to look after the women and children at home, from where he was on military duty at Fort Butler, near the present village of St. Jacobs, became alarmed as night approached and the children had not returned, and went in search of them, first going to his brother, Abel Moore's place to see if they were there. His wife, who was Mrs. Reagan's sister, also started on horseback to look for them, taking a different route from the one her husband took. His wife chose to go through the woods, and he walked along the wagon path. When Mrs. William Moore found the children lying by the road, she thought they had become tired and laid down to sleep. There was not sufficient light to tell the size or sex of the person, and she called over and over again the name of one and another of her children, supposing one of them to be asleep. She got down from her horse to pick up the youngest child, but just then, a crackling noise and flash of light from a burning hickory tree nearby alarmed her and, fearing Indians might be in ambush there, she grabbed the boy, Timothy, and sprang on her horse and reached home in advance of her husband. Although they did not meet until they both returned home, they both found the lifeless bodies in the darkness, lying by the wayside, and each placed a hand upon the bare shoulder of Mrs. Reagan.

The following has been taken from the '1882 Brink's History of Madison County': "What must have been her sensations as Mary 'Polly' Moore placed her hand upon the back of a naked corpse, and felt, on further examination, the quivering flesh from which the scalp had recently been torn? In the gloom of the night, she could indistinctly see the figure of the little child of Mrs. Reagan's sitting so near the body of its mother as to lean its head, first one side, then the other, on the insensible and mangled body, as she leaned over, the little one said - 'The black man raised his ax and cut them again.' She saw no further, but thrilled with horror and alarm, hastily remounted her frightened horse, and quickly hurried home where she heated water, intending by that means, to defend herself from the savage foe."

William Moore had not been long absent from his brother Abel before he returned, saying that someone had been killed by the Indians. He had discerned the body of a person lying on the ground, but whether wan or woman, it was too dark for him to see without a closer inspection than was deemed safe.

The habits of the Indians were too well known by these settlers to leave a man in Mr. Moore's situation free from the apprehension of an ambuscade still near. Thinking the Indians were having a general uprising, he wanted to warn the other people in the area and get them to safety.

From Abel's house, he took Abel's wife and her remaining children along with Hannah Bates; and they headed for William's house and his family, having no idea if his wife had returned from her search.

The first thought was to find refuge in the blockhouse. Mr. Moore desired his brother's family to go directly by the road to the blockhouse while he would pass by his own house and take his family to the fort with him. The night was dark, and the road passed through a heavy forest. Instead of going on alone without some protection, the women and children chose to accompany William Moore, though the distance to the Fort Wood River was thereby nearly doubled. The feelings of the party as they groped their way through the dark woods can be more easily imagined than described. Sorrow for the supposed loss of their relatives and children was mingled with horror at the manner of their death and fear for their own safety and pain at the dreadful idea that the remains of their dearest friends lay mangled on the cold ground near them while they were denied the privilege of seeing and preparing them for sepulture. Silently they passed on until they came to the home of William Moore, when he exclaimed, as if relieved from strained apprehension, "Thank God, Polly is not killed!" The horse which his wife had ridden was standing near the house. As they let down the bars and gained admission to the yard, his wife came running out, exclaiming, "They are killed by the Indians, I expect." The whole party then departed hastily for the blockhouse, to which place, all the neighbors, to whom warning had been communicated by signals, gathered by daybreak.

BURYING THE DEAD

The sight of Rachel and the six children lying by the roadside, all stripped of clothing, must have been horrifying. The bodies all showed signs of being bludgeoned by tomahawk, and all seven were scalped.

The bodies were collected for burial. They were all buried with boards laid on the bottom and the sides and above the bodies. There were no men to make coffins. The graves were dug with coffin-shaped vaults at the bottom, which was lined with slabs split from trees nearby as nearly like planks as possible; and after the bodies were placed in the vaults, they were covered over with the same kind of split slabs.

The seven were buried in three graves; Mrs. Reagan and her two children, Elizabeth and Timothy, in one grave; Captain Moore's two children, William and Joel, in another, and William Moore's two children, John and George, in the third.

Mr. Solomon Pruitt, who was not in the pursuit, assisted in the burial of the victims. He hauled them on a small one-horse sled to the burying ground south of Bethalto. There were no wagons in those days. There, a stone slab marks their resting place.

The Vaughn cemetery, in section 24, where the victims of the Wood River massacre were buried, was the first regular place of interment in the area. It antedates the year 1809. Here the first Baptist church in the township was built. Rev. William Jones, eminent as a legislator as well as a minister, was the first preacher. His descendants, or some of them, still live in the county and are worthy of their distinguished ancestry.

In this primitive cemetery, the inscriptions on various tombstones can still be deciphered. Among others appear the names of members of the Ogle, Odell, and Rattan families.

The original sandstone marker with the inscription: "William & Joel Moore was killed by the Indians July 10, 1814" was taken from this cemetery many years ago but can now be seen at the Alton Museum of History & Art.

PURSUING THE PERPETRATORS

A young man named John Harris, living at Able Moore's home, was sent that night on horseback bearing the sad tidings to Fort Russell, located in the township of that name, Captain Samuel Whiteside (Whiteside County, Illinois was named for General Samuel Whiteside, an Illinois officer in the War of 1812 and Black Hawk War.) commanding, and to Fort Butler, Captain Moore commanding, to give the alarm. Leaving the latter place about one o'clock the same night, about seventy of the rangers from both forts, among whom were James and Solomon Preuitt, had arrived at Moore's Fort about sunrise and proceeded to the scene of the tragedy.

Seven were missing, and their bodies lay mangled and bleeding within a mile of the fort in the dark forest. There was little rest that night at the fort. The women and children of the neighborhood, with the few men who were not absent with the rangers, crowded together, not knowing but that at any minute, the Indians might begin their attack.

The news soon spread, and it was not long before Captain Whiteside, and nine others gave pursuit. Among them were James Pruitt, Abraham Pruitt, William and John Sample, James Starkden, William Montgomery, and Peter Waggoner, whose descendants still live in Wood River and Moro townships.

They were enabled to follow the track of the broken limbs on the bushes which the Indians did, as was supposed to tantalize the helpless women, thinking there were no men able enough to pursue them. Further on, by the way, they made through the tall prairie grass, and also by blood. The Indians, when they learned they were pursued, frequently bled themselves to facilitate their speed and give them greater endurance.

The weather was extremely hot, and some of the ranger's horses gave out entirely. Their order was to keep up the pursuit.

The rangers pressed upon the fleeing red men. It was on the evening of the second day between sunset and dark that they came in sight of the Indians at a small stream entering the Sangamon River on the dividing ridge, about seventy miles distant in Morgan County. This site was named Indian Creek to remember what had taken place there.

There stood on the ridge, at that time, a lone cottonwood tree. Several Indians climbed this tree to look back. They saw their pursuers from that tree. They separated and went in different directions, all making for the timber. When the whites came to the tree, they, too, divided and pursued the Indians separately.

James and Abraham Pruitt, taking the trail of an Indian, soon came in sight of him, and the former, having the fastest horse, soon came within range of him. He rode up to within thirty yards and shot him in the thigh. The Indian fell but managed to get to a fallen treetop. Abraham soon came up, and they concluded to ride in on the Indian and finish him, which Abraham did by shooting and killing him where he lay. In the Indian's shot-pouch was found the scalp of Mrs. Reagan. The Indian tried to raise his gun to shoot but was too weak to fire. The Indian had also lost his flint, or he might have killed one of his pursuers. His rifle is supposed to be in the Pruitt family yet. The place where the Indians were overtaken was near where Virden now stands. The remaining Indians hid in the timber and the drift of the creek. It was learned, afterward, at the treaty of Galena that only one Indian escaped, and that was the chief who led the party.

Where was Reason Reagan? Some new light has been shed on reason's whereabouts on the day of the massacre. Samuel Thomas, Rachel's brother, states that reason was accompanied by his younger sister, Cathy, when he went to church on Sunday morning. Cathy was a young single woman who had recently come to the area; and, if she were to visit with anyone after church, she would have to be accompanied. It was summertime on a Sunday with no evident reason for concern. Cathy would eventually marry David Carter, who lived in the area. She may have known him by this time, or perhaps she was visiting with others. This provides a likely scenario for Reason's Sunday away from the family. In that era, it was not unusual to be unaware of happenings just a few miles away. None of our research as of yet had revealed when reason returned home and learned of his family's fate.

THE SURVIVING FAMILIES, MOVING ON

"Of those who took refuge in the fort that night, there is probably but one now living, Mrs. Nancy Hedden, a daughter of Captain Abel Moore. She resides at San Diego, California and was then about a year and a half old," stated V. P. Richmond in 1882.

George Moore married Peggy McFarlin on December 27, 1814, in Madison County, Illinois. George Moore had two children: Margaret and Walter Moore, while living in Madison County, Illinois.

Years later, Mr. Thomas S. Pinckard, who at the time was a resident of Springfield, Illinois, had kindly sent the following: "I have a vivid recollection of several of the old settlers who were living when I was a boy. Abel Moore, in his Dearborn wagon, with his wooden leg..."

One of the members of the church, Mrs. Bates, the mother of the wife of Abel Moore, lived near Jersey Landing; another, Mrs. Askew, sister-in-law of Mrs. Abel Moore, also lived near Jersey Landing, and yet both came monthly, on horseback, exposed to imminent danger and yet with great regularity and delight, to attend the stated appointments of the church. Mrs. Askew was Hannah Bates Askew. She married Josiah Askew.

Another gallant officer of Wood River township was the son of Abel, Maj. Frank Moore, the famous Civil War cavalry raider and leader. It was said of him by a certain major general on one occasion: "Maj. Moore has captured more prisoners than my whole army corps."

In the sale of the old Abel Moore's homestead, the Moore children reserved this sacred spot where the cabin of Abel once stood as a lasting tribute to their departed parents. This is where the fenced gravesite in Gordon Moore Park can be seen today.

Abel Moore died in 1846 at the age of 63. Mary Moore died the day before her husband, aged 61. They lie side by side on the very spot of ground where their pioneer cabin was constructed.

Before the massacre, William's family consisted of his wife, daughter, and two sons, John and George, both of whom were victims at the Wood River massacre.

Six children were born to the family afterward. When they moved to Pike County, Illinois, in 1830, they took four children with them. Rachel had married five years earlier. Rachel, Lorenzo, Enoch, and Matthew lived to maturity and had families of their own. Louisa, aged 13, died in 1831 in Pike County.

George had no children when he came to Madison County, but two were born while residing there, Margaret and Walter. The family migrated to Independence, Missouri, in 1837.

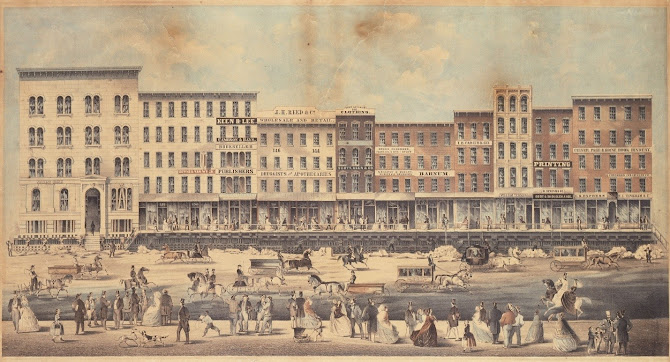

|

| A family visits the Wood River Massacre Monument, located off Fosterburg Road. 1910 |

Exclusive permission from author William Wilson.

Edited by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.