|

| Carriage traffic on Michigan Avenue. 1895 |

Friday, July 14, 2017

Christopher Columbus statue from the 1893 World's Fair in Lake Park, Chicago. 1895

Living History of Illinois and Chicago®

1893 World's Columbian Exposition,

Chicago,

Entertainment,

Memorials,

Photograph(s) Only,

Transportation

Monday, July 3, 2017

Chicago's United Airlines introduced the world's first stewardess service on flights between Chicago and San Francisco.

|

| This Boeing 80, is flying over the Streeterville neighborhood in the Near North Side community of Chicago. (circa 1928) |

The pilot and co-pilot sat in a separate forward cabin and were kept informed of changing weather conditions by two-way radio. The Model 80, which accommodated 12 passengers in a heated cabin had hot and cold running water, individual passenger reading lamps and leather upholstered seats, was soon redesigned to carry 18 passengers and designated the Model 80A. The 80A was powered with three 525 hp Pratt & Whitney “Hornet” engines with a cruising speed of 125 mph and a range of 460 miles. The gross weight was 17,500 pounds.

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, airline passenger travel was primarily the realm of Business people, the Rich and the Adventurous. The average person preferred to travel by train, boat or by private automobile.

An airline passenger paid up to $900 (one-way) to fly across the United States and upon arrival often found it necessary to transfer to a train or automobile to reach their final destination. There were few airports and were often located in relatively remote areas. Worst of all, the airplane cabins lacked sound-proofing. In addition to the unsettling noise, vibration was also a problem, one passenger stated that his glasses kept sliding down his nose the entire flight.

|

| Interior of the Boeing 80. (circa 1928) |

Compiled by Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Living History of Illinois and Chicago®

Chicago,

Illinois Business,

Transportation

Sunday, July 2, 2017

Chicago Photographer, Kenneth Heilbron, Chicago Ringling Brothers Barnum Bailey Circus Portfolio.

|

| Kenneth Heilbron |

In 1938 he became the first instructor of photography at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago where he taught until 1942. From the late 1930s through the 1940s, Heilbron became fascinated with photographing the Ringling Brothers Circus whenever they came to Chicago, even occasionally traveling with the circus and its performers. His photographs of circus life and the performers are some of the most intimate and penetrating ever taken.

Heilbron died in 1997 in Galena, Illinois and is buried in the Greenwood Cemetery in Galena. His archive is housed at the Art Institute of Chicago.

|

| Ringling Brothers Barnum Bailey Circus - Sideshow Barker - Chicago, 1939 |

|

| Ringling Brothers Barnum Bailey Circus - Clown "Pierre" - Chicago, 1941 |

|

| Ringling Brothers Barnum Bailey Circus - Clown "Honkalu" - Chicago, 1946 |

|

| Ringling Brothers Barnum Bailey Circus - Charlie Bell dog Trixie - Back Yard - Chicago, 1940 |

|

| Ringling Brothers Barnum Bailey Circus - Clown "Charlie Bell and Trixie" - Chicago, 1940 |

|

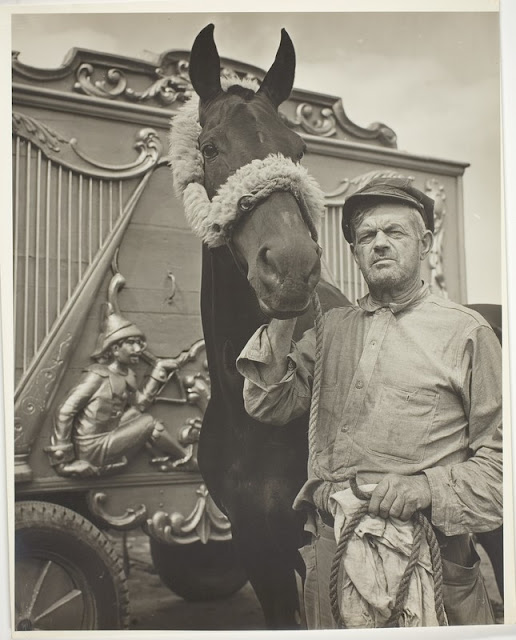

| Ringling Brothers Barnum Bailey Circus - Horse "Starlen Night" and Groom - Chicago, 1942 |

|

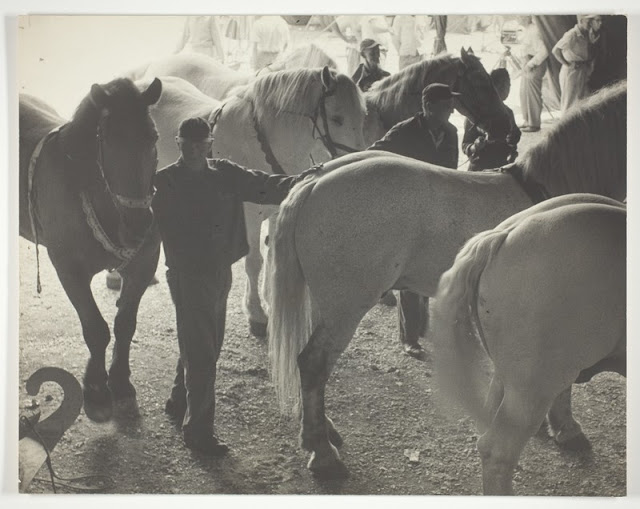

| Ringling Brothers Barnum Bailey Circus - Bareback Horses - Back Yard - Chicago, 1942 |

|

| Ringling Brothers Barnum Bailey Circus - Back Yard - Chicago, 1946 |

|

| Ringling Brothers Barnum Bailey Circus - Steam Cahize - Chicago, 1937 |

|

| Ringling Brothers Barnum Bailey Circus - Sideshow Visitors - Chicago, 1941 |

Ringling Brothers Barnum Bailey Circus - Chicago

Living History of Illinois and Chicago®

Art,

Chicago,

Education,

Famous,

Illinois Business

Stearns Limestone Quarry, now known as Palmisano Park in Chicago.

Stearns Limestone Quarry, stretching from 27th to 29th Street along Halsted and from 29th Street to Poplar in Bridgeport.

The quarry opened in 1836 by the Illinois Stone and Lime Company. A few years later one of the partners in the company, Marcus Cicero Stearns, took over operations and named the rapidly growing hole in the ground his company was digging after himself.

Stearns quarry provided much of the stone for downtown and the nearby Illinois and Michigan Canal. Stearns died in 1890 but the quarry continued to operate for another 80 years. By then enough limestone had been excavated that, at its lowest point, the hole reached 380 feet below street level and covered 27 acres.

After 1970, Stearns Quarry was used as a dumping ground for clean construction waste - wood, brick and other stone materials and ash. This continued until 1999, when the city decided they should probably make something worthwhile of the giant hole. Proposals were submitted by various city departments and the Chicago Park District's plan to fill the quarry and transform it into a nature park was approved.

According to Claudine Malick, who was a project manager for the plan, Palmisano Park is a "closed landfill" project approved by the Illinois EPA. Because the quarry was used as a landfill, the city retains ownership of the park for a fifteen-year period, at which point it transfers to the Park District.

The City approved the Park District's plan in 2004 and the District selected Site Design Group to enact the plan.

The park opened in 2009 as Site 39 (Stearns Quarry) Park and was rededicated in November of 2010 after Henry C. Palmisano (1951-2006), a Bridgeport resident who served as a member of Mayor Richard M. Daley’s fishing advisory committee and was an advocate and supporter of urban fishing. Palmisano's family ran an outdoor shop in the eastern edge of the neighborhood.

Over 40,000 square feet of topsoil was trucked in to cover the debris and be sculpted into what you see at the park today. "Because the Illinois EPA declared the quarry a closed landfill, nothing could be removed," said Malick. At its highest point, the park rises 33 feet above street level, giving visitors a beautiful view of the downtown skyline and surrounding neighborhoods.

The walkway runs 1.7 miles, including catwalks and a quarter-mile running track surrounding a soccer field at the southwest corner of the park, give visitors some incline for exercise.

At the northwest corner of the park the limestone walls serve as a backdrop for a retention pond stocked with goldfish, bluegill, large mouth bass and green sunfish. Fishing in the retention pond is catch and release only.

The pond itself is fed by rain and ground water via an underground piping system isolated from the rest of the neighborhood's storm drain system. The water from the pond is pumped to the northeast corner of the park and cascades back to the retention pond, providing aeration. Vegetation for the cascading system was chosen for its nativity to the area and for their ability to filter out urban pollutants. The deepest area of the retention pond is 14 feet and the elevator shafts that hauled miners down to the quarry were left untouched, to give the park a sense of history.

Part of the catwalks were constructed from reclaimed wood found in the quarry. Rocks peppered along the park were also found in the quarry and repurposed for usage in the park. As part of the process to turn the park into a nature preserve, the Park District has conducted controlled plantings of more native vegetation and burns of areas along the hill, to help foster its growth.

The hill has become popular among locals for sledding in winter, but the landscape architects incorporated the concrete barriers from the quarry's years as a landfill as barriers, so sledding is discouraged.

Visitors who walk in the park find themselves becoming disconnected from the street bustle along Halsted the deeper they go. By the time they reach the retention pond 40 feet below street level, the noise from Halsted Street can hardly be heard. It truly is an oasis in the middle of the city.

Compiled by Neil Gale, Ph.D.

The quarry opened in 1836 by the Illinois Stone and Lime Company. A few years later one of the partners in the company, Marcus Cicero Stearns, took over operations and named the rapidly growing hole in the ground his company was digging after himself.

Stearns quarry provided much of the stone for downtown and the nearby Illinois and Michigan Canal. Stearns died in 1890 but the quarry continued to operate for another 80 years. By then enough limestone had been excavated that, at its lowest point, the hole reached 380 feet below street level and covered 27 acres.

After 1970, Stearns Quarry was used as a dumping ground for clean construction waste - wood, brick and other stone materials and ash. This continued until 1999, when the city decided they should probably make something worthwhile of the giant hole. Proposals were submitted by various city departments and the Chicago Park District's plan to fill the quarry and transform it into a nature park was approved.

The City approved the Park District's plan in 2004 and the District selected Site Design Group to enact the plan.

The park opened in 2009 as Site 39 (Stearns Quarry) Park and was rededicated in November of 2010 after Henry C. Palmisano (1951-2006), a Bridgeport resident who served as a member of Mayor Richard M. Daley’s fishing advisory committee and was an advocate and supporter of urban fishing. Palmisano's family ran an outdoor shop in the eastern edge of the neighborhood.

Over 40,000 square feet of topsoil was trucked in to cover the debris and be sculpted into what you see at the park today. "Because the Illinois EPA declared the quarry a closed landfill, nothing could be removed," said Malick. At its highest point, the park rises 33 feet above street level, giving visitors a beautiful view of the downtown skyline and surrounding neighborhoods.

The walkway runs 1.7 miles, including catwalks and a quarter-mile running track surrounding a soccer field at the southwest corner of the park, give visitors some incline for exercise.

At the northwest corner of the park the limestone walls serve as a backdrop for a retention pond stocked with goldfish, bluegill, large mouth bass and green sunfish. Fishing in the retention pond is catch and release only.

|

| The Stearns Quarry Fountain was installed in 2009. |

The hill has become popular among locals for sledding in winter, but the landscape architects incorporated the concrete barriers from the quarry's years as a landfill as barriers, so sledding is discouraged.

Visitors who walk in the park find themselves becoming disconnected from the street bustle along Halsted the deeper they go. By the time they reach the retention pond 40 feet below street level, the noise from Halsted Street can hardly be heard. It truly is an oasis in the middle of the city.

Compiled by Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Living History of Illinois and Chicago®

Chicago,

Chicago Pre-1871 Fire,

Environmental,

Government,

Illinois Business

Saturday, July 1, 2017

Abraham Lincoln Life Masks.

One of the myths surrounding Abraham Lincoln is that a death mask was made after his assassination. In fact, Lincoln had two life masks done, five years apart. The first was produced by Leonard Volk in Chicago, Illinois, in April 1860. Clark Mills completed the second in February 1865 in Washington, D.C.

Abraham Lincoln Life Mask by Leonard Volk

In 1881, sculptor Leonard Volk explained how he made the first Lincoln mask. He met Lincoln in 1858 during Lincoln's campaign for the U.S. Senate and invited him to sit for a bust. Lincoln agreed, but it took Volk's insistence two years later before Lincoln came to his studio. By this time it was the spring of 1860, shortly before Lincoln received the Republican nomination for president.

Volk said, "My studio was in the fifth story, and there were no elevators in those days, and I soon learned to distinguish his steps on the stairs, and am sure he frequently came up two, if not three, steps at a stride." Volk took measurements of his head and shoulders and made a plaster cast of his face to reduce the number of sittings.

Of the plaster casting process, Volk said, "It was about an hour before the mold was ready to be removed, and being all in one piece, with both ears perfectly taken, it clung pretty hard, as the cheek-bones were higher than the jaws at the lobe of the ear. He bent his head low and took hold of the mold, and gradually worked it off without breaking or injury; it hurt a little, as a few hairs of the tender temples pulled out with the plaster and made his eyes water." Lincoln said he found the process "anything but agreeable."

Volk said that during the sittings, "he would talk almost unceasingly, telling some of the funniest and most laughable of stories, but he talked little of politics or religion during those sittings. He said: 'I am bored nearly every time I sit down to a public dining-table by someone pitching into me, on politics.'"

Volk left a priceless legacy for future sculptors, as attested by Avard Fairbanks, who said, "Virtually every sculptor and artist used the Volk mask for Lincoln. it is the most reliable document of the Lincoln face, and far more valuable than photographs, for it is the actual form."

Volk Casts the Hands in Springfield

Volk arrived in Lincoln's hometown of Springfield, Illinois, on May 18, 1860, the day Lincoln was nominated for president. He said, "I went straight to Mr. Lincoln's unpretentious little two-story house. He saw me from his door or window coming down the street, and as I entered the gate, he was on the platform in front of the door, and quite alone. His face looked radiant. I exclaimed: 'I am the first man from Chicago, I believe, who has the honor of congratulating you on your nomination for President.' Then those two great hands took both of mine with a grasp never to be forgotten." Volk told Lincoln he would be the next president and he wanted to make a statue of him. Once invited inside, Volk said he gave Mrs. Lincoln "a cabinet-size bust of her husband, which I had modeled from a large one, and happened to have with me."

Volk returned another day to cast Lincoln's hands. He wanted Lincoln to hold something in his right hand, so Lincoln produced a broom handle from his woodshed and began whittling the end of it. "I remarked to him that he need not whittle off the edges. 'Oh, well,' said he, 'I thought I would like to have it nice.' Volk did the casting in the dining room, and noticed "The right hand appeared swollen as compared with the left, on account of excessive hand-shaking the evening before; this difference is distinctly shown in the cast."

Volk visited the Lincoln home in January 1861, just weeks before Lincoln left for Washington. He said Lincoln "announced in a general way that I had made a bust of him before his nomination, and that he was then giving daily sittings at the St. Nicholas Hotel to another sculptor; that he had sat for him for a week or more, but could not see the likeness, though he might yet bring it out. 'But,' continued Mr. Lincoln, 'in two or three days after Mr. Volk commenced my bust, there was the animal himself.'"

Abraham Lincoln Life Mask by Clark Mills

On February 11, 1865, about two months before his death, Abraham Lincoln permitted sculptor Clark Mills to make this life mask of his face. This was the second and last life mask made of Lincoln. The strain of the presidency was written on Abraham Lincoln’s face.

Masks Show Changes in Lincoln's Life

John Hay, who served as one of Lincoln's White House secretaries, noticed that Lincoln "aged with great rapidity" during the Civil War. He said, "Under this frightful ordeal his demeanor and disposition changed -- so gradually that it would be impossible to say when the change began; but he was in mind, body, and nerves a very different man at the second inauguration from the one who had taken the oath in 1861."

Hay had seen both of Lincoln's life masks and remarked, "This change is shown with startling distinctness by two life-masks. The first is a man of fifty-one, and young for his years. The face has a clean, firm outline; it is free from fat, but the muscles are hard and full; the large mobile mouth is ready to speak, to shout, or laugh; the bold, curved nose is broad and substantial, with spreading nostrils; it is a face full of life, of energy, of vivid aspiration. The other is so sad and peaceful in its infinite repose that the famous sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens insisted, when he first saw it, that it was a death mask. The lines are set, as if the living face, like the copy, had been in bronze; the nose is thin, and lengthened by the emaciation of the cheeks; the mouth is fixed like that of an archaic statue; a look as of one on whom sorrow and care had done their worst without victory is on all the features; the whole expression is of unspeakable sadness and all-sufficing strength. Yet the peace is not the dreadful peace of death; it is the peace that passeth understanding."

Life Mask Inspires Poem

After Stuart Sterne saw a Lincoln life mask in a Washington museum he published this poem in the February 1890 edition of the Century magazine:

Abraham Lincoln Life Mask by Leonard Volk

In 1881, sculptor Leonard Volk explained how he made the first Lincoln mask. He met Lincoln in 1858 during Lincoln's campaign for the U.S. Senate and invited him to sit for a bust. Lincoln agreed, but it took Volk's insistence two years later before Lincoln came to his studio. By this time it was the spring of 1860, shortly before Lincoln received the Republican nomination for president.

|

| Leonard Volk completed the first mask in Chicago, Illinois, in April 1860 |

Of the plaster casting process, Volk said, "It was about an hour before the mold was ready to be removed, and being all in one piece, with both ears perfectly taken, it clung pretty hard, as the cheek-bones were higher than the jaws at the lobe of the ear. He bent his head low and took hold of the mold, and gradually worked it off without breaking or injury; it hurt a little, as a few hairs of the tender temples pulled out with the plaster and made his eyes water." Lincoln said he found the process "anything but agreeable."

Volk said that during the sittings, "he would talk almost unceasingly, telling some of the funniest and most laughable of stories, but he talked little of politics or religion during those sittings. He said: 'I am bored nearly every time I sit down to a public dining-table by someone pitching into me, on politics.'"

Volk left a priceless legacy for future sculptors, as attested by Avard Fairbanks, who said, "Virtually every sculptor and artist used the Volk mask for Lincoln. it is the most reliable document of the Lincoln face, and far more valuable than photographs, for it is the actual form."

Volk Casts the Hands in Springfield

Volk arrived in Lincoln's hometown of Springfield, Illinois, on May 18, 1860, the day Lincoln was nominated for president. He said, "I went straight to Mr. Lincoln's unpretentious little two-story house. He saw me from his door or window coming down the street, and as I entered the gate, he was on the platform in front of the door, and quite alone. His face looked radiant. I exclaimed: 'I am the first man from Chicago, I believe, who has the honor of congratulating you on your nomination for President.' Then those two great hands took both of mine with a grasp never to be forgotten." Volk told Lincoln he would be the next president and he wanted to make a statue of him. Once invited inside, Volk said he gave Mrs. Lincoln "a cabinet-size bust of her husband, which I had modeled from a large one, and happened to have with me."

|

| Volk's Cabinet-size Bust of Abraham Lincoln. |

Volk visited the Lincoln home in January 1861, just weeks before Lincoln left for Washington. He said Lincoln "announced in a general way that I had made a bust of him before his nomination, and that he was then giving daily sittings at the St. Nicholas Hotel to another sculptor; that he had sat for him for a week or more, but could not see the likeness, though he might yet bring it out. 'But,' continued Mr. Lincoln, 'in two or three days after Mr. Volk commenced my bust, there was the animal himself.'"

Abraham Lincoln Life Mask by Clark Mills

On February 11, 1865, about two months before his death, Abraham Lincoln permitted sculptor Clark Mills to make this life mask of his face. This was the second and last life mask made of Lincoln. The strain of the presidency was written on Abraham Lincoln’s face.

|

| Clark Mills completed the second mask in February 1865 in Washington, D.C. |

John Hay, who served as one of Lincoln's White House secretaries, noticed that Lincoln "aged with great rapidity" during the Civil War. He said, "Under this frightful ordeal his demeanor and disposition changed -- so gradually that it would be impossible to say when the change began; but he was in mind, body, and nerves a very different man at the second inauguration from the one who had taken the oath in 1861."

Hay had seen both of Lincoln's life masks and remarked, "This change is shown with startling distinctness by two life-masks. The first is a man of fifty-one, and young for his years. The face has a clean, firm outline; it is free from fat, but the muscles are hard and full; the large mobile mouth is ready to speak, to shout, or laugh; the bold, curved nose is broad and substantial, with spreading nostrils; it is a face full of life, of energy, of vivid aspiration. The other is so sad and peaceful in its infinite repose that the famous sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens insisted, when he first saw it, that it was a death mask. The lines are set, as if the living face, like the copy, had been in bronze; the nose is thin, and lengthened by the emaciation of the cheeks; the mouth is fixed like that of an archaic statue; a look as of one on whom sorrow and care had done their worst without victory is on all the features; the whole expression is of unspeakable sadness and all-sufficing strength. Yet the peace is not the dreadful peace of death; it is the peace that passeth understanding."

Life Mask Inspires Poem

After Stuart Sterne saw a Lincoln life mask in a Washington museum he published this poem in the February 1890 edition of the Century magazine:

Ah, countless wonders, brought from every zone, Not all your wealth could turn the heart away F from that one semblance of our common clay, The brow where on the precious life long flown, Leaving a homely glory all its own, Seems still to linger, with a mournful play Of light and shadow! — His, who held a swayAnd power of magic to himself unknown,Through what is granted but God's chosen few, Earth's crownless, yet anointed kings, — a soul Divinely simply and sublimely true In that unconscious greatness that shall blessThis petty world while stars their courses roll, Whose finest flower is self-forgetfulness.Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Living History of Illinois and Chicago®

Abraham Lincoln,

Government

Tuesday, June 27, 2017

Looking south on Broadway from Wilson Avenue, Chicago. 1910

Living History of Illinois and Chicago®

Chicago,

Photograph(s) Only

The History of Millstadt, Illinois.

Millstadt is a village in St. Clair County, Illinois, at the crossing of Illinois Route 163 (locally known as "Jefferson Avenue") and Illinois Route 158 (locally known as "Washington Avenue").

The village is known for its German heritage, with more than half its people of German descent. The population was 3,924 at the 2014 census, an increase of 40% since the 2000 census.

THE EARLY SETTLERS

The earliest settlers of the Millstadt area were of English ancestry and had come from the 13 original states. The first land entries in Millstadt Township were first claimed in payment for military services rendered in the late 1700s. These first claims were made to George Lunceford, Thomas Marrs, and Mary Groot, the widow of Sergeant Jacob Groot, who died about 1788. The land was issued to Thomas Marrs and was surveyed in 1782 in Millstadt Township.

George Lunceford is usually considered the first white settler to have lived near present-day Millstadt. He was a native of Virginia and had been a soldier under George Rogers Clark during the capture of Kaskaskia and Prairie du Rocher in 1778. His land was surveys 429 and 430 in Sugar Loaf Heights. In 1796, Lunceford and Samuel Judy started a farm near Sugar Loaf, which in 1800 became the sole property of Mr. Lunceford.

The following year in 1801, a group of settlers arrived from Hardy County, Virginia. This group was led by the Baptist preacher David Badgley and included the families of Abraham Eyman, born in Lancaster, PA, William Miller from Virginia, and John Teter. They came by flatboat down the Ohio River to Shawneetown and then overland by horse to this area of St. Clair County, Illinois. In 1802 they were joined by the families of Martin Randleman from Lincoln County, North Carolina and Daniel Stookey from Hagerstown, Maryland.

The following year in 1801, a group of settlers arrived from Hardy County, Virginia. This group was led by the Baptist preacher David Badgley and included the families of Abraham Eyman, born in Lancaster, PA, William Miller from Virginia, and John Teter. They came by flatboat down the Ohio River to Shawneetown and then overland by horse to this area of St. Clair County, Illinois. In 1802 they were joined by the families of Martin Randleman from Lincoln County, North Carolina and Daniel Stookey from Hagerstown, Maryland.

In 1813, Thomas Harrison is supposed to have erected here one of the first cotton gins in Illinois. It was propelled by horsepower but was soon abandoned. Joshua W. Hughes {ancestor of billionaire Howard Hughes} came from Virginia and was the first blacksmith (1829) and coal operator (1830) in Millstadt Township. His mine was about a half mile southeast of Millstadt. The Hughes family left the Millstadt area around 1851 and settled in Scotland County, Missouri, where Joshua died in 1901.

The first church in Millstadt Township was built in 1819 on five acres of land donated by Phillemon Askins {another ancestor of the late Howard Hughes}. The church was called the Union Meeting House (Methodist Protestant), and it was located about a mile east of Millstadt on Route 158. The church burned on March 31, 1881. Adjoining this church was Union Hill Cemetery, the first cemetery in Millstadt Township. The first burials there were John Ross on October 1, 1823, and Thomas Jarrott on October 16, 1823.

GERMAN SETTLEMENT, 1828-1840

Prior to 1834, the following German settlers, who were mostly farmers, had settled in what is now Millstadt Township: Johannes Briesacher (1828); Anton Wagner, Johann Adam Krick, Carl Grossmann, Johannes Hax, Peter Vollmer, Johannes Eckert, and J. Christian Lindenstruth (1832); Adam Haas, Nicolaus Hertel, Johannes Freivogel Sr., and John Weible (1833).

The first large group of German settlers to arrive in the Millstadt area came from villages near Kaiserslautern in the Rhineland-Pfalz area of Germany. According to existing records at the Zion Evangelical Church (a German Church), this first group left Germany on September 4, 1834, and traveled to America on the Ship Ruthelin, which arrived in New Orleans, Louisiana, on November 17, 1834. The group then traveled by boat up the Mississippi River to St. Louis, where they disembarked for St. Clair County, Illinois. It is recorded that they settled in the Millstadt area on November 30, 1834.

This first group of settlers included the families of Daniel Mueller from Konken; Daniel Wagner from Doerrenbach; Jacob Dewald from Schellweiler; Jacob Weingardt and Jacob Weber from Rehweiler; Henry Jacob Gerlach from Mittelbach; Jacob Schuff and Johann Nicolaus Schmalenberger from Schrollbach; and Theobald Mueller from Quirnbach. Other settlers that came that same year (1834) were the families of Leonhard Baltz from Gross-Bieberau; Valentine Gruenewald from Rossdorf; George Mittelstetter from Reinheim; William Probst from Koelleda; Heinrich Mueller from Harpertshausen; Leonhard Kropp from Crumbach; and George Kuntz from Alzey. This early group of settlers then attracted large numbers of additional German families.

Many of these early settlers attended the German church of Zion Evangelical Church, which was first located in Section 21 of Millstadt Township. Zion was founded on Jan. 17, 1836, at the log cabin home of Johannes Freivogel. The first minister was Rev. Johann Jacob Riess, who served at Zion from 1836 to October 1846. He arrived in St. Clair County in November 1835. Rev. Riess was sent by the Basel Missionary Society in Switzerland because of letters sent to that society by the German settlers in the county who wanted a German-speaking minister.

Rev. Riess preached throughout St. Clair County, and services were first held at Zion only once a month. At the same time, he was also serving congregations at Dutch Hill, Turkey Hill, and Prairie du Long. In nice weather, the members met in the forest and in bad weather in the Freivogel cabin. The first log church of Zion was dedicated on June 26, 1837, and was built along very simple lines. Freivogel Cemetery, consisting of 40 acres, was deeded to the Zion congregation in April 1838 by Johann Nicolaus Schmahlenberger and his wife, Mary Katherine.

The early German Catholic settlers in the area worshipped at a log church that was built about two miles southwest of Millstadt. It was called St. Thomas the Apostle Chapel and was dedicated on November 26, 1837, by Bishop Joseph Rosati of St. Louis, who on that same day opened the parish register. The present-day location would be in Section 20 of Millstadt Township, near the intersection of Illinois Route 158 and Bohleysville Road. The 1958 dedication program for St. James' new school states the log church was on the farm of Edward Roenicke. The place was also called Johnson Settlement. It is also reported that a few parishioners were buried around this first log church. It is recorded by Rev. J. F. R. Loisel of Cahokia that he said the first mass for the new congregation of St. Thomas in the home of James Powers on Nov. 17, 1836. The first 3 trustees of St. Thomas were elected on Jan. 24, 1837, and were John O'Brien, James Powers & Bernard Slocy. St. Thomas was a mission church and did not have a resident priest but was served by priests from the surrounding area. The first baptism was recorded on December 10, 1837, by R. Loisel. St. Thomas gradually declined after a new brick church was built in Millstadt in 1851. The new congregation was called St. James.

Additional German immigrants continued to settle here in the 1840s, with a second large wave beginning in 1848 after political turmoil in Germany. There were also numerous families who settled in this area that came from the Alsace-Lorraine area. The ownership of that area in Europe varied between France and Germany. Still, the residents usually spoke German and fit in with other Germans who had settled previously in the Millstadt area.

Many of these early German settlers were farmers who came here seeking better farmland and better economic conditions. Many of the settlers were also escaping the political, social, and economic turmoil that the German states were experiencing at that time. Most wanted a better life for themselves and more opportunities for their children. This German immigration was so large in the Millstadt area that the 1881 History of St. Clair County reported that “only seven families of English descent” were still residing there.

Most of the first Germans who settled in this area did not know the English language, and few had the time or opportunity to learn it. Many preferred to use their native German in almost everything that concerned their life, including business, social organizations, church services and records, public notices, tombstone inscriptions, letters, and wills. Some of the earlier English-speaking settlers did not always get along well with their newly arrived German neighbors; some called the Germans clanish and unfriendly.

THE FOUNDING OF CENTREVILLE

The founding of the town of Millstadt dates back to 1836 when Simon Stookey was having a barn built a short distance north of present-day Millstadt. Joseph Abend and Henry Randleman were helping him, and it was proposed to Randleman that another piece of his land in Section 9 would make a most eligible town site. Abend proposed the name “Centerville” for the new town since it would be seven miles from Belleville, seven miles from Columbia, and seven miles from Pittsburg Lake. Henry agreed, and the town of Centerville was platted and surveyed on March 13, 1837. It originally consisted of only 40 lots. That part of town was bounded roughly by Washington, Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe streets. Some of the earliest purchasers of lots were: John & George Briesacher on September 4, 1837; George Heckler on August 28, 1838; and Evan Baird on November 26, 1839. Later additions to the town were made as the existing lots were sold out.

HOW MILLSTADT GOT ITS NAME

Although the village name was officially spelled as “Centerville” in the records of the Recorder of Deeds of St. Clair County, the German settlers usually used the European spelling of “Centreville.” George Kuntz was appointed the town’s first postmaster on June 7, 1843. When the application was first made for a post office at “Centreville,” that name was rejected in Washington, DC, since there was already a post office in Centreville in Wabash County, Illinois.

It is reported that the petitioners then translated the name “Centreville” into German and came up with the name 'Mittlestadt' or 'Middlestadt.' Either the writing was not clear, or the officials in Washington could not read the German writing because the name that was approved was “Millstadt."

Thus from 1843-1878, the people in town lived in Centreville but got their mail at the Millstadt Post Office. On September 14, 1878, the Board of Trustees of the Village of Centreville passed a revised ordinance to change the village's name to the ‘Village of Millstadt,” so the village name and the post office name were the same.

FAMOUS MILLSTADT RESIDENCES

The village is known for its German heritage, with more than half its people of German descent. The population was 3,924 at the 2014 census, an increase of 40% since the 2000 census.

THE EARLY SETTLERS

The earliest settlers of the Millstadt area were of English ancestry and had come from the 13 original states. The first land entries in Millstadt Township were first claimed in payment for military services rendered in the late 1700s. These first claims were made to George Lunceford, Thomas Marrs, and Mary Groot, the widow of Sergeant Jacob Groot, who died about 1788. The land was issued to Thomas Marrs and was surveyed in 1782 in Millstadt Township.

George Lunceford is usually considered the first white settler to have lived near present-day Millstadt. He was a native of Virginia and had been a soldier under George Rogers Clark during the capture of Kaskaskia and Prairie du Rocher in 1778. His land was surveys 429 and 430 in Sugar Loaf Heights. In 1796, Lunceford and Samuel Judy started a farm near Sugar Loaf, which in 1800 became the sole property of Mr. Lunceford.

In 1813, Thomas Harrison is supposed to have erected here one of the first cotton gins in Illinois. It was propelled by horsepower but was soon abandoned. Joshua W. Hughes {ancestor of billionaire Howard Hughes} came from Virginia and was the first blacksmith (1829) and coal operator (1830) in Millstadt Township. His mine was about a half mile southeast of Millstadt. The Hughes family left the Millstadt area around 1851 and settled in Scotland County, Missouri, where Joshua died in 1901.

The first church in Millstadt Township was built in 1819 on five acres of land donated by Phillemon Askins {another ancestor of the late Howard Hughes}. The church was called the Union Meeting House (Methodist Protestant), and it was located about a mile east of Millstadt on Route 158. The church burned on March 31, 1881. Adjoining this church was Union Hill Cemetery, the first cemetery in Millstadt Township. The first burials there were John Ross on October 1, 1823, and Thomas Jarrott on October 16, 1823.

GERMAN SETTLEMENT, 1828-1840

Prior to 1834, the following German settlers, who were mostly farmers, had settled in what is now Millstadt Township: Johannes Briesacher (1828); Anton Wagner, Johann Adam Krick, Carl Grossmann, Johannes Hax, Peter Vollmer, Johannes Eckert, and J. Christian Lindenstruth (1832); Adam Haas, Nicolaus Hertel, Johannes Freivogel Sr., and John Weible (1833).

The first large group of German settlers to arrive in the Millstadt area came from villages near Kaiserslautern in the Rhineland-Pfalz area of Germany. According to existing records at the Zion Evangelical Church (a German Church), this first group left Germany on September 4, 1834, and traveled to America on the Ship Ruthelin, which arrived in New Orleans, Louisiana, on November 17, 1834. The group then traveled by boat up the Mississippi River to St. Louis, where they disembarked for St. Clair County, Illinois. It is recorded that they settled in the Millstadt area on November 30, 1834.

This first group of settlers included the families of Daniel Mueller from Konken; Daniel Wagner from Doerrenbach; Jacob Dewald from Schellweiler; Jacob Weingardt and Jacob Weber from Rehweiler; Henry Jacob Gerlach from Mittelbach; Jacob Schuff and Johann Nicolaus Schmalenberger from Schrollbach; and Theobald Mueller from Quirnbach. Other settlers that came that same year (1834) were the families of Leonhard Baltz from Gross-Bieberau; Valentine Gruenewald from Rossdorf; George Mittelstetter from Reinheim; William Probst from Koelleda; Heinrich Mueller from Harpertshausen; Leonhard Kropp from Crumbach; and George Kuntz from Alzey. This early group of settlers then attracted large numbers of additional German families.

Many of these early settlers attended the German church of Zion Evangelical Church, which was first located in Section 21 of Millstadt Township. Zion was founded on Jan. 17, 1836, at the log cabin home of Johannes Freivogel. The first minister was Rev. Johann Jacob Riess, who served at Zion from 1836 to October 1846. He arrived in St. Clair County in November 1835. Rev. Riess was sent by the Basel Missionary Society in Switzerland because of letters sent to that society by the German settlers in the county who wanted a German-speaking minister.

Rev. Riess preached throughout St. Clair County, and services were first held at Zion only once a month. At the same time, he was also serving congregations at Dutch Hill, Turkey Hill, and Prairie du Long. In nice weather, the members met in the forest and in bad weather in the Freivogel cabin. The first log church of Zion was dedicated on June 26, 1837, and was built along very simple lines. Freivogel Cemetery, consisting of 40 acres, was deeded to the Zion congregation in April 1838 by Johann Nicolaus Schmahlenberger and his wife, Mary Katherine.

The early German Catholic settlers in the area worshipped at a log church that was built about two miles southwest of Millstadt. It was called St. Thomas the Apostle Chapel and was dedicated on November 26, 1837, by Bishop Joseph Rosati of St. Louis, who on that same day opened the parish register. The present-day location would be in Section 20 of Millstadt Township, near the intersection of Illinois Route 158 and Bohleysville Road. The 1958 dedication program for St. James' new school states the log church was on the farm of Edward Roenicke. The place was also called Johnson Settlement. It is also reported that a few parishioners were buried around this first log church. It is recorded by Rev. J. F. R. Loisel of Cahokia that he said the first mass for the new congregation of St. Thomas in the home of James Powers on Nov. 17, 1836. The first 3 trustees of St. Thomas were elected on Jan. 24, 1837, and were John O'Brien, James Powers & Bernard Slocy. St. Thomas was a mission church and did not have a resident priest but was served by priests from the surrounding area. The first baptism was recorded on December 10, 1837, by R. Loisel. St. Thomas gradually declined after a new brick church was built in Millstadt in 1851. The new congregation was called St. James.

Additional German immigrants continued to settle here in the 1840s, with a second large wave beginning in 1848 after political turmoil in Germany. There were also numerous families who settled in this area that came from the Alsace-Lorraine area. The ownership of that area in Europe varied between France and Germany. Still, the residents usually spoke German and fit in with other Germans who had settled previously in the Millstadt area.

Many of these early German settlers were farmers who came here seeking better farmland and better economic conditions. Many of the settlers were also escaping the political, social, and economic turmoil that the German states were experiencing at that time. Most wanted a better life for themselves and more opportunities for their children. This German immigration was so large in the Millstadt area that the 1881 History of St. Clair County reported that “only seven families of English descent” were still residing there.

Most of the first Germans who settled in this area did not know the English language, and few had the time or opportunity to learn it. Many preferred to use their native German in almost everything that concerned their life, including business, social organizations, church services and records, public notices, tombstone inscriptions, letters, and wills. Some of the earlier English-speaking settlers did not always get along well with their newly arrived German neighbors; some called the Germans clanish and unfriendly.

THE FOUNDING OF CENTREVILLE

The founding of the town of Millstadt dates back to 1836 when Simon Stookey was having a barn built a short distance north of present-day Millstadt. Joseph Abend and Henry Randleman were helping him, and it was proposed to Randleman that another piece of his land in Section 9 would make a most eligible town site. Abend proposed the name “Centerville” for the new town since it would be seven miles from Belleville, seven miles from Columbia, and seven miles from Pittsburg Lake. Henry agreed, and the town of Centerville was platted and surveyed on March 13, 1837. It originally consisted of only 40 lots. That part of town was bounded roughly by Washington, Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe streets. Some of the earliest purchasers of lots were: John & George Briesacher on September 4, 1837; George Heckler on August 28, 1838; and Evan Baird on November 26, 1839. Later additions to the town were made as the existing lots were sold out.

HOW MILLSTADT GOT ITS NAME

Although the village name was officially spelled as “Centerville” in the records of the Recorder of Deeds of St. Clair County, the German settlers usually used the European spelling of “Centreville.” George Kuntz was appointed the town’s first postmaster on June 7, 1843. When the application was first made for a post office at “Centreville,” that name was rejected in Washington, DC, since there was already a post office in Centreville in Wabash County, Illinois.

It is reported that the petitioners then translated the name “Centreville” into German and came up with the name 'Mittlestadt' or 'Middlestadt.' Either the writing was not clear, or the officials in Washington could not read the German writing because the name that was approved was “Millstadt."

Thus from 1843-1878, the people in town lived in Centreville but got their mail at the Millstadt Post Office. On September 14, 1878, the Board of Trustees of the Village of Centreville passed a revised ordinance to change the village's name to the ‘Village of Millstadt,” so the village name and the post office name were the same.

FAMOUS MILLSTADT RESIDENCES

- Miles Henry Davis - Father of jazz trumpeter Miles Davis, he owned a 160-acre estate in Millstadt.

- John Kasper - Member of the 1998 USA Olympic Bobsled Team.

- Garrett Schlecht - Baseball player, an outfielder for the Chicago Cubs.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Living History of Illinois and Chicago®

Government,

IL West Central

The History of the City of Chicago Municipal Tuberculosis Sanitarium.

Tuberculosis is an infectious disease of the lungs and other organs. Once considered incurable, the disease caused its victims to slowly waste away, so it was called "consumption." With a mortality rate of approximately 18 per 10,000 people, tuberculosis was a leading cause of death within the city of Chicago at the turn of the twentieth century.

In 1911, Chicago bought 158 acres to establish the Sanitarium in today's North Park Village Nature Center on Bryn Mawr at Pulaski. It operated from 1915 through the 1970s.

In 1914, there were 10,000 registered cases of Tuberculosis (TB). The number of deaths due to TB in Chicago that year was 3,384. Yet there were only 300 public beds available in the city for patients who could not afford to pay for treatment. In March 1915, the Municipal Tuberculosis Sanitarium opened its doors to the citizens of Chicago suffering from tuberculosis, and treatment was free to residents of Chicago.

At its opening, MTS was the largest Sanitarium of its kind and the first to have a Maternity Ward and Nursery. There were 32 buildings completed when it opened, and the main ones were connected by an underground tunnel. More buildings were added in later years. The TB Sanitarium was located on Chicago's North Side, on the grounds of what is now Peterson Park and North Park Village.

Some buildings are still standing, looking the same on the outside as in 1915. The Sanitarium was designed as a place for quiet and rest on the city's outskirts, and significant consideration was given to the exterior of the buildings and beautiful grounds.

By the 1950s and 1960s, the disease incidence was drastically reduced through improved public hygiene, vaccines and antimicrobial drugs. When the Sanitarium became under-used by the 1970s, Chicago redeveloped the property as North Park Village to include senior citizen housing, a school for the developmentally disabled, a nature preserve, and parkland. In 1977, the Chicago Park District began leasing and redeveloping the site.

Read the 1915 "Municipal control of tuberculosis in Chicago. City of Chicago Municipal Tuberculosis Sanitarium, its history and provisions." Report to the Mayor.

Early attempts at controlling tuberculosis in Chicago focused on home sanitation, public health education, and patient isolation. Private hospitals took a few tuberculosis patients, but public consumptive facilities were unavailable.

To raise public awareness, the Visiting Nurses Association and physician Theodore Sachs spearheaded an antituberculosis movement in the early 1900s. This eventually resulted in the passage of state legislation, the Glackin Tuberculosis Law, in 1909, giving the city of Chicago the ability to raise funds for treating and controlling tuberculosis through a special property tax.

In 1911, Chicago bought 158 acres to establish the Sanitarium in today's North Park Village Nature Center on Bryn Mawr at Pulaski. It operated from 1915 through the 1970s.

In 1914, there were 10,000 registered cases of Tuberculosis (TB). The number of deaths due to TB in Chicago that year was 3,384. Yet there were only 300 public beds available in the city for patients who could not afford to pay for treatment. In March 1915, the Municipal Tuberculosis Sanitarium opened its doors to the citizens of Chicago suffering from tuberculosis, and treatment was free to residents of Chicago.

Some buildings are still standing, looking the same on the outside as in 1915. The Sanitarium was designed as a place for quiet and rest on the city's outskirts, and significant consideration was given to the exterior of the buildings and beautiful grounds.

Read the 1915 "Municipal control of tuberculosis in Chicago. City of Chicago Municipal Tuberculosis Sanitarium, its history and provisions." Report to the Mayor.

Living History of Illinois and Chicago®

Chicago,

Disasters,

Environmental,

Historic Buildings

Monday, June 26, 2017

Chicago Daily News Fresh Air Fund Sanitarium. (1920-1939)

Designed in 1913 and constructed in 1920, the "Theatre on the Lake" was originally built as the Chicago Daily News Fresh Air Fund Sanitarium. It was preceded by two successive open-air "floating hospitals" in Lincoln Park that was built between the 1870s and the 1900s on piers on Lake Michigan.

The breezes through these wooden shelters were believed to cure babies suffering from tuberculosis and other diseases. In 1914, the Chicago Daily News offered to fund a more permanent sanitarium building.

Constructed in 1920 on a landfill area, the impressive Prairie style structure was one of several Lincoln Park buildings designed by Dwight H. Perkins of the firm Perkins, Fellows, and Hamilton. Perkins, an important Chicago social reformer and Prairie School architect designed several Lincoln Park buildings including Café Brauer, the Lion House in the Lincoln Park Zoo, and the North Pond Café.

The Chicago Daily News Sanitarium building was constructed in brick with a steel arched pavilion with 250 basket baby cribs, nurseries, and rooms for older children.

Free health services, milk and lunches were provided to more than 30,000 children each summer until 1939, when the sanitarium closed.

Major reconstruction of Lake Shore Drive led to the demolition of the building's front entrance. During World War II, the structure became an official recreation center for the United Service Organization (USO).

The Chicago Park District converted the building to Theatre on the Lake in 1953, located at Fullerton Avenue and Lake Shore Drive, that offers breathtaking views of Lake Michigan.

Compiled by Neil Gale, Ph.D.

The breezes through these wooden shelters were believed to cure babies suffering from tuberculosis and other diseases. In 1914, the Chicago Daily News offered to fund a more permanent sanitarium building.

|

| The Chicago Daily News "Fresh Air" Sanitarium. |

|

| Empty hammocks hanging from the ceiling and baby carriages parked against a wall inside the Chicago Daily News Sanitarium. |

|

| Women reaching toward a child lying in a hammock inside the Chicago Daily News Sanitarium. |

|

| Nine female nurses holding babies, standing and sitting on a wall in front of the Chicago Daily News Sanitarium. |

|

| Children playing a circle game on a slope of grass with the Chicago Daily News Sanitarium in the background across Lake Shore Drive. |

The Chicago Park District converted the building to Theatre on the Lake in 1953, located at Fullerton Avenue and Lake Shore Drive, that offers breathtaking views of Lake Michigan.

Compiled by Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Living History of Illinois and Chicago®

Chicago,

Education,

Entertainment,

Environmental,

Government,

News Story

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)