From 1908–1940, Sears, Roebuck, and Co. sold about 100,000 homes, not including cabins, cottages, garages, outhouses, and farm buildings, through their mail-order Modern Homes program. Over that time, Sears designed 447 different housing styles, from the elaborate multistory Ivanhoe, with its elegant French doors and art glass windows, to the simpler Goldenrod, which served as a quaint, three-room and no-bath cottage for summer vacationers. (An outhouse could be purchased separately for Goldenrod and similar cottage dwellers.) Customers could choose a house to suit their individual tastes and budgets.

Sears was not an innovative home designer. Sears was instead a very able follower of popular home designs but with the added advantage of modifying houses and hardware according to buyer tastes. Individuals could even design their own homes and submit the blueprints to Sears, which would then ship off the appropriate precut and fitted materials, putting the homeowner in full creative control. Modern Home customers had the freedom to build their own dream houses, and Sears helped realize these dreams through quality custom design and favorable financing.

Designing a Sears Home

The process of designing your Sears house began as soon as the Modern Homes catalog arrived at your doorstep. Over time, Modern Homes catalogs came to advertise three lines of homes aimed at customers’ differing financial means: Honor Bilt, Standard Built, and Simplex Sectional.

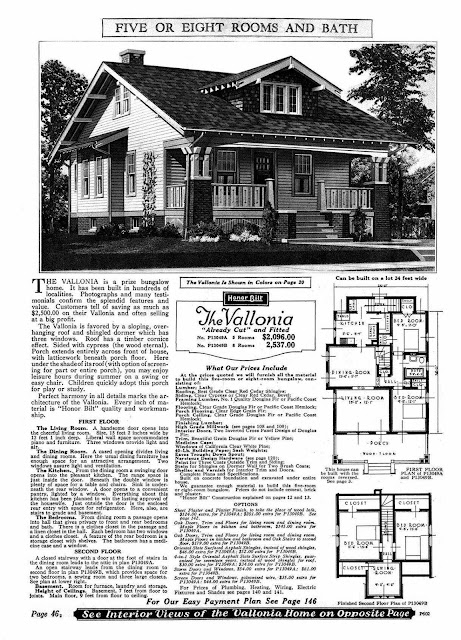

Honor Bilt homes were the most expensive and finest quality sold by Sears. Joists, studs, and rafters were to be spaced 14 3/8 inches apart. Attractive cypress siding and cedar shingles adorned most Honor Bilt exteriors. And depending on the room, interiors featured clear-grade (i.e., knot-free) flooring and inside trim made from yellow pine, oak, or maple wood. Sears’s catalogs also reported that Standard Built homes were best for warmer climates, meaning they did not retain heat very well. The Simplex Sectional line, as the name implies, contained simple designs. Simplex houses were frequently only a couple of rooms and were ideal for summer cottages.

You may see many houses that partially or even closely resemble a house that you own or have seen. Look closely because the floor plan may be reversed, a dormer may have been added, or the original buyer may have chosen brick instead of wood siding. Plumbing may look like it was added after construction, or storm windows may appear on the house but not in the catalog’s illustration.

All of this and more are possible because the Modern Homes program encouraged custom-designed houses down to the color of the cabinetry hardware. The difficulty in identifying a Sears home is just a reflection of the unique design and tastes of the original buyer (see FAQs).

Construction

As mentioned above, Sears was not an innovator in home design or construction techniques; however, Modern Home designs did offer distinct advantages over other construction methods. The ability to mass-produce the materials used in Sears homes lessened manufacturing costs, which lowered purchase costs for customers. Not only did precut and fitted materials shrink construction time up to 40%, but Sears’s use of "balloon style" framing, drywall, and asphalt shingles greatly eased construction for homebuyers.

"Balloon style" framing. These framing systems did not require a team of skilled carpenters, as previous methods did. Balloon frames were built faster and generally only required one carpenter. This system uses precut timber of mostly standard 2x4s and 2x8s for framing. Precut timber, fitted pieces, and the convenience of having everything, including the nails, shipped by railroad directly to the customer added greatly to the popularity of this framing style.

Drywall. Before drywall, plaster and lathe wall-building techniques were used, which again required skilled carpenters. Sears Homes took advantage of the new home-building material of drywall by shipping large quantities of this inexpensively manufactured product with the rest of the housing materials. Drywall offers the advantages of low price, ease of installation, and added fire-safety protection. It was also a good fit for the square design of Sears Homes.

Asphalt shingles. It was during the Modern Homes program that large quantities of asphalt shingles became available. The alternative roofing materials available included, among others, tin and wood. Tin was noisy during storms, looked unattractive, and required a skilled roofer, while wood was highly flammable. Asphalt shingles, however, were cheap to manufacture and ship, as well as easy and inexpensive to install. Asphalt had the added incentive of being fireproof.

Modern Conveniences

Sears helped popularize the latest technology available to modern home buyers in the early part of the twentieth century. Central heating, indoor plumbing, and electricity were all new developments in home design that Modern Homes incorporated, although not all of the homes were designed with these conveniences. Central heating not only improved the livability of homes with little insulation but also improved fire safety, always a worry in an era where open flames threatened houses and whole cities, in the case of the Chicago Fire.

Sears Modern Homes program stayed abreast of any technology that could ease the lives of its home-buyers and gave them the option to design their homes with modern convenience in mind. Indoor plumbing and homes wired for electricity were the first steps to modern kitchens and bathrooms.

History of Sears Modern Homes

The hour has arrived. Dad gathers Mom and Sis into the carriage. He hops in the wagon with his brothers to ride off to the railroad station. The day and hour have come to greet the first shipment of your family’s brand-new house. All the lumber will be precut and arrive with instructions for your dad and uncles to assemble and build. Mom and Dad picked out Number 140 from Sears, Roebuck, and Company’s catalog. It will have two bedrooms and a cobblestone foundation, plus a front porch—but no bath. They really wanted Number 155, with a screened-in front porch, built-in buffet, and an inside bath, but $1,100 was twice as much as Dad said he could afford. In just a few days, the whole family will sleep under the roof of your custom-made Sears Modern Home.

Entire homes would arrive by railroad, from precut lumber to carved staircases, down to the nails and varnish. Families picked out their houses according to their needs, tastes, and pocketbooks. Sears provided all the materials and instructions and, for many years, the financing for homeowners to build their own houses. Sears’s Modern Homes stand today as living monuments to the fine, enduring, and solid quality of Sears craftsmanship.

No official tally exists of the number of Sears mail-order houses that still survive today. It is reported that more than 100,000 houses were sold between 1908 and 1940 through Sears’s Modern Homes program. The keen interest evoked in current homebuyers, architectural historians, and enthusiasts of American culture indicates that thousands of these houses survive in varying degrees of condition and original appearance.

It is difficult to appreciate just how important the Modern Homes program and others like it were to homebuyers in the first half of the twentieth century. Imagine for a moment buying a house in 1908. Cities were getting more crowded and had always been dirty breeding grounds for disease in an age before vaccines. The United States was experiencing a great economic boom, and millions of immigrants who wanted to share in this wealth and escape hardship were pouring into America’s big cities. City housing was scarce, and the strong economy raised labor costs, which sent new home prices soaring.

The growing middle class was leaving the city for the—literally—greener pastures of suburbia as trolley lines and the railroad extended lifelines for families who needed to travel to the city. Likewise, companies were building factories on distant, empty parcels of land and needed to house their workers. Stately, expensive Victorian-style homes were not options for any but the upper class of homeowners. Affordable, mail-order homes proved to be just the answer to such dilemmas.

Sears was neither the first nor the only company to sell mail-order houses, but they were the largest, selling as many as 324 units in one month (May of 1926). The origin of the Modern Homes program is actually to be found a decade before houses were sold. Sears began selling building materials out of its catalogs in 1895, but by 1906, the department was almost shut down until someone had a better idea. Frank W. Kushel, who was reassigned to the unprofitable program from managing the China department, believed the home-building materials could be shipped straight from the factories, thus eliminating storage costs for Sears. This began a successful 25-year relationship between Kushel and the Sears Modern Homes program.

To advertise the company’s new and improved line of building supplies, a Modern Homes specialty catalog, the Book of Modern Homes and Building Plans, appeared in 1908. For the first time, Sears sold complete houses, including the plans and instructions for the construction of 22 different styles, announcing that the featured homes were "complete, ready for occupancy." By 1911, Modern Homes catalogs included illustrations of house interiors, which provided homeowners with blueprints for furnishing the houses with Sears appliances and fixtures.

It should be noted that suburban families were not the only Modern Home dwellers. Sears expanded its line to reflect the growing demand from rural customers for ready-made buildings. In 1923, Sears introduced two new specialty catalogs, Modern Farm Buildings and Barn.

The barn catalog boasted "a big variety of scientifically planned" farm buildings, from corncribs to tool sheds. The simple, durable, and easy-to-construct nature of the Sears farm buildings made them particularly attractive to farmers.

Modern Homes must have seemed like pennies from heaven, especially to budget-conscious first-time homeowners. For example, Sears estimated that, for a precut house with fitted pieces, it would take only 352 carpenter hours as opposed to 583 hours for a conventional house—a 40% reduction! Also, Sears offered loans beginning in 1911, and by 1918 it offered customers credit for almost all building materials as well as offering advanced capital for labor costs. Typical loans ran at 5 years, with 6% interest, but loans could be extended over as many as 15 years.

Sears’s liberal loan policies eventually backfired, however, when the Depression hit. 1929 saw the high point of sales with more than $12 million, but $5.6 million of that was in mortgage loans. Finally, in 1934, $11 million in mortgages were liquidated, and despite a brief recovery in the housing market in 1935, the Modern Homes program was doomed. By 1935, Sears was selling only houses, not lots or financing, and despite the ever-brimming optimism of corporate officials, Modern Homes sold its last house in 1940.

Between 1908 and 1940, Modern Homes made an indelible mark on the history of American housing. A remarkable degree of variety marks the three-plus decades of house design by Sears. A skilled but mostly anonymous group of architects designed 447 different houses. Each of the designs, though, could be modified in numerous ways, including reversing floor plans, building with brick instead of wood siding, and many other options.

Between 1908 and 1940, Modern Homes made an indelible mark on the history of American housing. A remarkable degree of variety marks the three-plus decades of house design by Sears. A skilled but mostly anonymous group of architects designed 447 different houses. Each of the designs, though, could be modified in numerous ways, including reversing floor plans, building with brick instead of wood siding, and many other options.Sears had the customer in mind when it expanded its line of houses to three different expense levels to appeal to customers of differing means. While Honor Bilt was the highest-quality line of houses, with its clear-grade (no knots) flooring and cypress or cedar shingles, the Standard Built and Simplex Sectional lines were no less sturdy, yet were simpler designs and did not feature precut and fitted pieces.

Simplex Sectional houses actually included farm buildings, outhouses, garages, and summer cottages.

The American landscape is dotted by Sears Modern Homes. Few of the original buyers and builders remain to tell the excitement they felt when traveling to greet their new house at the train station. The remaining homes, however, stand as testaments today to that bygone era and to the pride of homes built by more than 100,000 Sears customers and fostered by the Modern Homes program.

|

| This photo was taken soon after the construction of the Sears Homes was complete, and the sidewalks were paved. |

Carlinville, Illinois, has the largest single collection of Sears kit homes in the United States. Beginning in 1917, Carlinville saw its population grow by one-third when Standard Oil of Indiana opened two new coal mines. An influx of young European immigrants coming to work the mines caused the town’s population to swell from 4,000 to 6,000, creating a severe housing shortage.

Standard Oil officials found a solution to this crisis in an unlikely place: Sears and Roebuck. For the first time, people could order home kits in a variety of models through the Sears mail-order catalog. Eight different models were selected for Standard Addition, ranging in price from $3,000 to $4,000, with the company placing an order for $1 million for homes, the largest in Sears history. By the end of 1918, 156 of the mail-order homes had been placed within a nine-block neighborhood on the northeast side of town.

In 1926, Standard Oil executives determined they could buy coal cheaper than mining it themselves, and they made the decision to close the mines. The closure devastated the town and required years before it fully recovered. The workers moved away, mostly to other mines, and abandoned the housing to the ravages of time and the occasional party-goers from nearby Blackburn University. Standard Addition remained largely vacant until the mid-1930s when the houses were offered for sale to the public. Families could purchase one of the run-down five-room homes for $250 and a six-room model for $500. Even in the midst of the Great Depression, comparable homes were selling for $4,000, so it was an incredible bargain for lucky buyers.

Today, 152 of the original 156 homes still stand. Four no longer exist on their original sites; three were destroyed by fire, and one was moved to the country. As the largest single repository of Sears Homes in the United States, Standard Addition has been the subject of several documentaries and has attracted the attention of architects and nostalgia buffs from around the globe.

Step inside - The story of my private tour of a Sears Modern Home in Carlinville, Illinois.

Chronology of the Sears Modern Home Program

1895–1900

Building supplies are sold through Sears, Roebuck, and Company general catalog 1906. Sears considered closing its unprofitable building supplies department.

Frank W. Kushel (formerly manager of the China department) took over the building supplies department and realized supplies could be shipped directly from the factory, thus saving storage costs.

1908

The first specialty catalog issued for houses, Book of Modern Homes and Building Plans, featuring 22 styles ranging in price from $650–2,500.

1909

Mansfield, LA, lumber mill purchased. The first bill of materials sold for complete Modern Home.

1910

Home designers added gas and electric light fixtures.

1911

Cairo, IL, lumber mill opens. First mortgage loan issued (typically 5–15 years at 6% interest).

1912

Norwood, OH, millwork plant purchased.

1913

Mortgages were transferred to the credit committee. Mortgages were later discontinued.

1916

Mortgages revived. Ready-made production began. The popular “Winona” was introduced and featured in catalogs through 1940. The first applied roofing office opened in Dayton, OH.

1917

Standard Oil Company purchased 156 houses for its mineworkers in Carlinville, Illinois (approximately $1 million), completed in 1918.

1917–21

No money-down financing was offered.

1919

The First Modern Homes sales office opened in Akron, OH. Modern Homes catalog featured the Standard Oil housing community.

1920

Philadelphia plant became the East Coast base. Sears averaged nearly 125 units shipped per month.

1921

Pittsburgh, Cleveland, Cincinnati, and Dayton sales offices opened.

1922

Chicago, Philadelphia, and Washington sales offices opened. Honor Bilt homes feature deluxe kitchens with white-tile sink and drainboards and white, enameled cupboards.

1924

Columbus, OH, a sales office opened.

1925

Detroit sales office opened; Philadelphia became the East branch of Modern Homes. Newark, NJ, lumber mill began.

1926

Cairo, IL, plant ships 324 units in one month (May). Honor Bilt homes feature “Air-Sealed-Wall construction,” which encloses every room with a “sealed air space” to increase insulation.

1929

Sears began supervising the construction of homes. Sears shiped an average of 250 units per month from Cairo, IL. Nearly 49,000 units sold to this point. The program’s high point of sales reached ($12,050,000); nearly half, however, is tied up in mortgage loans as the stock market crashes.

1930

Sears had 350 different salespeople working in 48 sales offices. Home specialty catalog proclaims Sears the “World’s Largest Home Builders.”

1933

Mortgage financing discontinued. Construction supervision was abandoned, except in greater New York City. Modern Homes catalog featured models of Mount Vernon and New York City’s Federal Hall.

1934

Annual Report announced the Modern Homes department was discontinued. All mortgage accounts were liquidated ($11 million). Steel-framed, air-conditioned Modern Home exhibit featured at the Century of Progress World’s Fair.

1935

Sears reopened the housing department. Offered only houses, no financing or construction.

Houses were prefabricated by General Houses, Incorporated (Chicago).

1936

Sales reached $2 million.

1937

Sales reached $3.5 million. The last appearance of the department in the general catalog.

1938

Sales reached $2.75 million.

1940

Cairo, IL, millwork plant sold to the employees who used their profit-sharing money to make the purchase. Last catalog issued (Book of Modern Homes). Sears ends the Modern Homes program, having sold more than 100,000 units, not including cabins, cottages, garages, outhouses, and farm buildings.

Below is an alphabetical list of houses and prices as they were advertised in the Sears Modern Homes catalogs. Some models were available in different years. Not all models are represented. The description and floor plan, as featured in the catalogs are shown below.

BY MODEL NUMBER

1908-1939

Model Number 024; ($704 to $1,400)

Model Number 034; ($930 to $1,750)

Model Number 036; ($601 to $1,200)

Model Number 052; ($782 to $1,995)

Model Number 059; ($163 to $765)

Model Number 064; ($556, $1, 525)

Model Number 070; ($492 to $1,275)

Model Number 101; ($738 to $1,740)

Model Number 101; ($738 to $1,740)

Model Number 104; ($580 to $1,425)

Model Number 104; ($580 to $1,425)

Model Number 105; ($545 to $1,175)

Model Number 105; ($545 to $1,175)

Model Number 106; ($498 to $1,190)

Model Number 107; ($107 to $650)

Model Number 107; ($107 to $650)

Model Number 112; ($891 to $2,000)

Model Number 113; ($1,062 to $1,270)

Model Number 116; ($790 to $1,700)

Model Number 116; ($790 to $1,700)

Model Number 117; ($807 to $921)

Model Number 119; ($1,518 to $1,731)

Model Number 120; ($1,278 to $1,660)

Model Number 122; ($915 to $1,043)

Model Number 123; ($1,163 to $1,404)

Model Number 125; ($587 to $844)

Model Number 126; ($675 to $814)

Model Number 130; ($1,783 to $2,152)

Model Number 131; ($1,491 to $1,870)

Model Number 134; ($459 to $578)

Model Number 135; ($733 to $853)

Model Number 136; ($628 to $767)

Model Number 137; ($1,140 to $1,342)

Model Number 139; ($449 to $567)

Model Number 139; ($449 to $567)

Model Number 141; ($419 to $531)

Model Number 142; ($153 to $298)

Model Number 143; ($712 to $896)

Model Number 144; ($829 to $926)

Model Number 147; ($680 to $872)

Model Number 153; ($1,142)

Model Number 154; ($2,287 to $2,702)

Model Number 155; ($1,080 to $1,118)

Model Number 157; ($1,521 to $1,866)

Model Number 158; ($1,548 to $1,845)

Model Number 159; ($548 to $762)

Model Number 163; ($1,110 to $1,282)

Model Number 164; ($1,259 to $1,623)

Model Number 165; ($1,374 to $1,518)

Model Number 166; ($1,001 to $1, 095)

Model Number 174; ($795 to $940)

Model Number 175; (1232); ($815 to $1,732)

Model Number 176; ($1,455 to $2,141)

Model Number 177; ($1,050 to 1,461)

Model Number 178; ($1,250 to $1,611)

Model Number 182; ($902)

Model Number 183; ($745 to$908)

Model Number 186; ($746 to $790)

Model Number 188; ($926 to $984)

Model Number 190; ($828 to $894)

Model Number 191; ($892 to $966)

Model Number 193; ($599 to $656)

Model Number 194; ($599 to $656)

Model Number 195; ($619 to $670)

Model Number 196; ($599 to $656)

Model Number 198; ($834)

Model Number 200; ($1,528 to $1,663)

Model Number 202; ($1,389)

Model Number 204; ($1,318)

Model Number 205; ($707 to $744)

Model Number 207; ($1,148 to $1,174)

Model Number 208; ($814)

Model Number 216; ($402)

Model Number 225; ($1,281 to $1,465)

Model Number 226; ($822 to $1,555)

Model Number 228; ($1,182 to $1,280)

Model Number 229, ($670-$714)

Model Number 241; ($412 to $429)

Model Number 243; ($1,006 to $1,037)

Model Number 264; ($819)

Model Number 264; ($897 to $919)

Model Number 301; ($1,261)

Model Number 306; ($1,363 to $1,561)

ALPHABETICAL

The Adams; (3059, 3059A); ($4,721)

The Adeline; (2099, 7099); ($696 to $971)

The Albany; (P13199); ($2,232)

The Alberta; (C107); ($330 to $596)

The Albion; (3227); ($2,496 to $2,515)

The Alden; (3366); ($2,418 to $2,571)

The Alhambra; (2090, 7080, 17090A); ($1,969 to $3,134)

The Almo; (2033, 2033B); ($463 to $1,052)

The Alpha; (7031, 7031); ($871 to $1,356)

The Alton; (2019); ($814 to $1,150)

The Altona; (121); ($697 to $1,458)

The Americus; (3063); ($1,924 to $2,173)

The Amherst; (3388); ($1,608 to $1,917)

The Amhurst; (P3244); ($2,825)

The Amsterdam; (3196A); ($3,641 to $4,699)

The Arcadia; (2032); ($267 to $946)

The Ardara; (3039); ($1,773 to $3,485)

The Argyle; (2018, 17018); ($827 to $2150)

The Arlington; (145); ($1,294 to $2,906)

The Ashland; (C5253); ($2,847 to $2,998)

The Ashmore; (3034); ($1,608 to $3,632)

The Atlanta; (247); ($2,240 to $4,492)

The Attleboro; (3384); ($1,810 to $2,197)

The Auburn; (2046, 3199, 3382); ($1,638 to $3,624)

The Aurora; (3352A, 3352B, 3000); ($989, $2,740)

The Avalon; (3048); ($1,967 to $2,539)

The Avoca; (109); ($590 to $1,754)

The Avondale; (151); ($1,198 to $2,657)

The Bandon; (3058); ($2,499 to $4,317)

The Barrington; (C3260, P3241, P3260); ($2,329 to $2,606)

The Bayside; (3410); (No price given)

The Beaumont; (3037); ($2,136 to $2,374)

The Bedford; (3249A, 3249B); ($2,242 to $2,673)

The Belfast; (3367A); ($1,604 to $1,698)

The Bellewood; (3304); (No price given)

The Belmont; (237); ($1,204 to $2,558)

The Berkley; (3401A, 3401B); ($1,110 to $1,435)

The Berkshire; (3374); ($1,564)

The Berwyn; (3274); ($1,249)

The Betsy Ross; (3089); ($1,412 to $1,654)

The Birmingham; (3332); (No price given)

The Bonita; (197); ($619 to $1,207)

The Branford; (3712); $2,010

The Bristol; (3370); ($2,958)

The Brookside; (2091); ($1,050 to $1,404)

The Brookwood; (3033); ($1,328)

The Bryant; (3411); (No price given)

The Calumet; (3001); ($3,073)

The Cambria; (251); ($998 to $1,771)

The Cambridge; (3289); (No price given)

The Canton; (152); ($251 to $750)

The Cape Cod; (13354A, 13354B)

The Carlin; (3031); ($1,172)

The Carlton; (3002); ($5,118)

The Carrington; (3353); (No price given)

The Carroll; (3344); (No price given)

The Carver; (3408); ($1,291)

The Castleton; (227); ($934 to $2,193)

The Cedars; (3278); ($2,334)

The Chateau; (3378); ($1,365)

The Chatham; (3396); ($1,667)

The Chelsea; (111); ($943 to $2,740)

The Chester; (3380); ($1,433 to $1,535)

The Chesterfield; (P3235); ($2,934)

The Chicora; (2031, 031) ($257 to $798)

The Claremont; (3273); ($1,437)

The Clarissa; (127); ($1,357 to $2,670)

The Cleveland; (C3233); (2,463 to $2,739)

The Clifton; (3305); ($1,660)

The Clyde; (118); ($1,397 to $2,924)

The Colchester; (3292, 3292A); ($1,988 to $2,256)

The Colebrook; (3707, 3707A); ($1,608 to $1,728)

The Collingwood; (3280); ($1,329 to $1,960)

The Columbine; (8013); ($1,971 to $2,135)

The Concord; (2021, 114, 3379); ($815 to $2,546)

The Conway; (3052A, 3052B); ($1,310 to $2,099)

The Cornell; (3226A, 3226B); ($1,360 to $1,785)

The Corning; (3357); (No price given)

The Corona; (240); ($1,537 to $3,364)

The Crafton; (3318A, 3318C, 3318D); ($916 TO $1,399)

The Cranmore; (185); ($637 to $1,283)

The Crescent; (3084, 3086); ($925 to $2,410)

The Croydon; (3718); ($1,407)

The Culver; (3322); ($873)

The Dartmouth; (3372); ($2,648 to $2,864)

The Davenport; (3346); (No price given)

The Dayton; (3407); ($1,247)

The Del Rey; (3065); ($1,978 to $2,557)

The Delevan; (2028, 028); ($285 to $949)

The Delmar; (3210); ($2,220)

The Detroit; (3336); ($1,431)

The Dexter; (3331); (No price given)

The Dover; (3262); ($1,613 to $2,311)

The Dundee; (3051); ($733 to $1,405)

The Durham; (8040); ($2,498 to $2,775)

The Edgemere; (199); ($647 to $1,124)

The Ellison; (3359); ($2,185 to $2,845)

The Ellsworth; (3341); ($1,178 to $1,236)

The Elmhurst; (3300); (No price given)

The Elmwood; (162); ($716 to $2,492)

The Elsmore; (2013); ($858 to $2,391)

The Estes; (6014); ($617 to $672)

The Fair Oaks; (3282); ($972)

The Fairfield; (No number given); (No price given)

The Fairy; (3216, 3217); ($965 to $993)

The Farnum; (6017); ($917 to $942)

The Ferndale; (3284); ($1,340 to $1,790)

The Flossmoor; (180); ($838 to $2,124)

The Fosgate; (6016); ($616 to $722)

The Franklin; (3405); ($1,118)

The Fullerton; (3205); ($1,633 to $2,294)

The Fulton; (3702); ($1,667)

The Gainsboro; (3387); ($1,475 to $1,548)

The Galewood; (3294); ($1,252)

The Garfield; (P3232); ($2,599 to $2,758)

The Gateshead; (3386); ($1,345 to $1,392)

The Gladstone; (3222); ($1,409 to $2,153)

The Glen Falls; (P3265); ($4,560 to $4,909)

The Glen View; (3381); ($3,375 to $3,718)

The Glendale; (148); ($916 to $2,188)

The Glyndon; (156); ($595 to $1,990)

The Gordon; (3356); (No price given)

The Grant; (6018); ($947 to $999)

The Greenview; (115); ($443 to $1,462)

The Hamilton; (102, 150); ($1,023 to $2,385)

The Hammond; (3347); ($1,253 to $1,408)

The Hampshire; (3364); (No price given)

The Hampton; (3208); ($1,551 to $1,681)

The Harmony; (3056, 13056); ($1,599 to $2,220)

The Hartford; (3352A, 3352B); (No price given)

The Hathaway; (3082); ($1,196 to $1,970)

The Haven; (3088); ($1,584)

The Haverhill; (3368); ($2,276 to $2,585)

The Hawthorne; (201); ($1,488 to $2,792)

The Hazelton; (172); ($780 to $2,248)

The Hillrose; (3015); ($1,553 to $3,242)

The Hillsboro; (3308); ($2,215 to $2,803)

The Hollywood; (1259, 12069); ($1,376 to $2,986)

The Homecrest; (3398); ($2,010 to $2,017)

The Homestead; (3376); ($1,319 to $1,566)

The Homeville; (3072); ($1,741 to ($1,896)

The Homewood; (P3238); ($2,610 to $2,809)

The Honor; (3071); ($2,747 to $3,278)

The Hopeland; (3036); ($2,622 to $2,914)

The Hudson; (6013, 6013A); ($495 to $659)

The Ionia; (7034, 17034); ($695 to $1,038)

The Ivanhoe; (230); ($1,663 to $2,618)

The Jeanette; (3283, 3283A); ($1.661)

The Jefferson; (3349); ($3,350)

The Jewel; (3310); (No price given)

The Josephine; (7044); ($998 to $1,464)

The Katonah; (2029, 029); ($265 to $827)

The Kendale; (3298); ($1,358)

The Kilbourne; (7013); ($2,500 to 2,780)

The Kimball; (6015); ($635 to $638)

The Kimberly; (P3261); ($1,442 to $1,815)

The Kismet; (216A, 2002); ($428 to $1,148)

The La Salle; (3243); ($2,530 to $2,746)

The Lakecrest; (3333); (No price given)

The Lakeland; (129); ($1,533 to $3,972)

The Langston; (181A, 2000); ($796 to $1,898)

The Laurel; (P3275); ($1,912)

The Lebanon; (3029); ($1,092 to $1,465)

The Lenox; (3395); ($1,164)

The Letona; (192); ($619 to $1,215)

The Lewiston; (3287, 3287A); ($1,527 to $2,037)

The Lexington; (3045); ($2,958 to $4,365)

The Lorain; (214); ($1,030 to $2,558)

The Lorne; (3053, 13053); ($1,286 to $2,002)

The Lucerne; (103); ($582 to $1,390)

The Lynn; (3716); ($1,342)

The Lynnhaven; (3309); ($2,227 to $2,393)

The Madelia; (3028); ($1,393 to $1,953)

The Magnolia; (2089); ($5,140 to $5,972)

The Malden; (3721); ($2,641)

The Manchester; (C3250); ($2,655 to $2,934)

The Mansfield; (3296); ($2,292)

The Maplewood; (3302); (No price given)

The Marina; (2024); ($1,289 to $1632)

The Marquette; (3046); ($1,862 to $2,038)

The Martha Washington; (3080); ($2,688 to $3,727)

The Matoka; (168); ($950 to $1,920)

The Mayfield; (3326); ($1,082 to $1,189)

The Maytown; (167); ($645 to $2,038)

The Maywood; (C3232); ($2,658 to $2,914)

The Medford; (3720A, 3720B); ($1,715 to $2,068)

The Melrose; (P3286); ($1,698)

The Milford; (3385); ($1,359 to $1,671)

The Millerton; (3358); (No price given)

The Milton; (210); ($1,520 to $2,491)

The Mitchell; (3263); ($1,493 to $2,143)

The Monterey; (3312); ($2,998)

The Montrose; (C3239); ($2,923 to $3,324)

The Morley; (2097); ($837)

The Mt. Vernon; (55C1910); ($851 to $1,221)

The Nantucket; (3719A, 3719B); ($1,360 to $1,536)

The Natoma; (2034, 034); ($191 to $598)

The New Haven; (3338); (No price given)

The Newark; (3285); ($2,048 to $2,678)

The Newbury; (3397); ($1,791 to $2,042)

The Newcastle; (3402); ($1,576 to $1,813)

The Niota; (161); ($788 to $1,585)

The Nipigon; (No number given); (No price given)

The Normandy; (3390); ($1,598 to $1,867)

The Norwich; (3342); ($2,952)

The Norwood; (2095); ($948 to $1,667)

The Oak Park; (3288); ($2,227 to $3,265)

The Oakdale; (149); ($1,549 to $3,067)

The Oldtown; (3383); ($1,322)

The Olivia; (7028); ($1,123 to $1,283)

The Oxford; (3393A, 3393B); ($808 to $999)

The Palmyra; (132); ($1,993 to $3,459)

The Paloma; (2035); ($688 to $1,418)

The Parkside; (3325); ($1,259)

The Pennsgrove; (3348); (No price given)

The Phoenix; (160); ($1,043 to $2,077)

The Pineola; (2098); ($489 to $659)

The Pittsburgh; (C3252); ($1,827 to $1,838)

The Plymouth; (3323); ($1,132 to $1,206)

The Portsmouth; (3413); (No price given)

The Prescott; (P3240); ($1,715 to $1,873)

The Princeton; (3204); ($3,073)

The Princeville; (173); ($810 to $1,794)

The Priscilla; (3229); ($2,998 to $3,198)

The Puritan; (3190); ($1,947 to $2,475)

The Ramsay; (6012); ($654 to $685)

The Randolph; (3297); (No price given)

The Rembrandt; (P3215A, P3215B); ($2,383 to $2,770)

The Rest; (7004); ($923 to $1,083)

The Richmond; (3360); ($1,692)

The Ridgeland; (3302); ($1,293 to $1,496)

The Riverside; (3324); ($1,200 to $1,257)

The Roanoke; (1226); ($1,784 to $1,982)

The Rochelle; (3282); ($1,170)

The Rockford; (C3251); ($2,086 to $2,278)

The Rockhurst; (3074); ($1,979 to $2,468)

The Rodessa; (7041, 3203); ($998 to $1,189)

The Roseberry; (2037); ($744 to $4,479)

The Rosita; (2036, 2043, 2044); ($314 to $875)

The Rossville; (171); ($452 to $1,096)

The Roxbury; (3340); ($1,459)

The Salem; (3211); ($2,496 to $2,634)

The San Jose; (P6268); ($2,026 to $2,138)

The Saranac; (2030, 030); ($248 to $927)

The Saratoga; (2087); ($1,468 to $3,506)

The Savoy; (2023); ($1,230 to $2,333)

The Schuyler; (3371); ($2,974)

The Seagrove; (2048); ($1,854)

The Selby; (6011); ($590 to $629)

The Sheffield; (P3266); ($2,033 to $2,098)

The Sherburne; (187); ($1,231 to $2,581)

The Sheridan; (3224); ($2,095 to $2,256)

The Sherwood; (P3279); ($2,445)

The Silverdale; (110); ($1,623)

The Solace; (3218); ($1,476 to $1,581)

The Somers; (P17008); ($1,696 to $1,778)

The Somerset; (2008); ($732 TO $1,576)

The Spaulding; (P3257); ($2,281)

The Springfield; (133); ($660 to $1,516)

The Springwood; (3078); ($1,797 to $2,089)

The Stanford; (3354A, 3354B); (No Price Given)

The Starlight; (2009); ($543 to $1,645)

The Stone Ridge; (3044); ($1,995 to $2,229)

The Stratford; (3290); ($2,122)

The Strathmore; (3306); ($1,627 to $1,757)

The Sumner; (2027, 027); ($237 to $853)

The Sunbury; (3350A, 3350B); ($1,141 to $1,237)

The Sunlight; (3221); ($1,499 to $1,620)

The Sunnydell; (3079, 3979); ($1,571 to $1,746)

The Tarryton; (C3247); ($2,967 to $2,998)

The Torrington; (3355); ($3,189)

The Trenton; (3351); (No price given)

The Uriel; (3052); ($1,374 to $1,527)

The Valley; (6000); ($904 to $989)

The Vallonia; (3049); ($1,465 to $2,479)

The Van Dorn; (P3234); ($1,576 to $2,249)

The Van Jean; (C3267A, C3267B); ($2,499 to $2,899)

The Van Page; (P3242); ($2,650)

The Verndale; (6003); ($900 to $1,130)

The Verona; (3201); ($2,461 to $4,347)

The Vinemont; (6002); ($747 to $830)

The Vinita; (6001); ($1,154 to $1,240)

The Wabash; (2003); ($507 to $1,217)

The Walton; (3050); ($2,225 to $2,489)

The Wareham; (203); ($1,089 to $2,425)

The Warren; (13703); ($1,506)

The Warrenton; (3030); ($1,288)

The Waverly; (3321); ($1,234)

The Wayne; (3210); ($1,994 to $2,121)

The Wayside; (107B, 2004); ($372 to $945)

The Webster; (3369); ($3,204)

The Wellington; (3223); ($1,760 to $1,998)

The Westly; (2026, 3085); ($926 to $2,543)

The Wexford; (3337A, 3337B); (No Price Given)

The Wheaton; (3312); ($1,235)

The Whitehall; (181); ($687 to $1,863)

The Willard; (3265); ($1,477 to $1,997)

The Wilmore; (3327); ($1,191 to $1,414)

The Windermere; (1208); ($3,410 to $3,534)

The Windsor; (3193); ($1,216 to $1,605)

The Winona; (2010A, 2010B); ($744 to $1,998)

The Winona; (C2010, C2010B); ($744 to $1,998)

The Winthrop; (P3264); ($1,921)

The Woodland; (2007); ($938 to $2,480)

The Worchester; (3291); ($2,315)

The Yates; (3711, 3711A); ($1,812 to $2,058)

105 Sears Modern Home Fact Sheets with Floor Plans.

Copyright © 2013. Sears Brands, LLC. All rights reserved.

The Adeline; (2099, 7099); ($696 to $971)

The Albany; (P13199); ($2,232)

The Alberta; (C107); ($330 to $596)

The Albion; (3227); ($2,496 to $2,515)

The Alden; (3366); ($2,418 to $2,571)

The Alhambra; (2090, 7080, 17090A); ($1,969 to $3,134)

The Almo; (2033, 2033B); ($463 to $1,052)

The Alpha; (7031, 7031); ($871 to $1,356)

The Alton; (2019); ($814 to $1,150)

The Altona; (121); ($697 to $1,458)

The Americus; (3063); ($1,924 to $2,173)

The Amherst; (3388); ($1,608 to $1,917)

The Amhurst; (P3244); ($2,825)

The Amsterdam; (3196A); ($3,641 to $4,699)

The Arcadia; (2032); ($267 to $946)

The Ardara; (3039); ($1,773 to $3,485)

The Argyle; (2018, 17018); ($827 to $2150)

The Arlington; (145); ($1,294 to $2,906)

The Ashland; (C5253); ($2,847 to $2,998)

The Ashmore; (3034); ($1,608 to $3,632)

The Atlanta; (247); ($2,240 to $4,492)

The Attleboro; (3384); ($1,810 to $2,197)

The Auburn; (2046, 3199, 3382); ($1,638 to $3,624)

The Aurora; (3352A, 3352B, 3000); ($989, $2,740)

The Avalon; (3048); ($1,967 to $2,539)

The Avoca; (109); ($590 to $1,754)

The Avondale; (151); ($1,198 to $2,657)

The Bandon; (3058); ($2,499 to $4,317)

The Barrington; (C3260, P3241, P3260); ($2,329 to $2,606)

The Bayside; (3410); (No price given)

The Beaumont; (3037); ($2,136 to $2,374)

The Bedford; (3249A, 3249B); ($2,242 to $2,673)

The Belfast; (3367A); ($1,604 to $1,698)

The Bellewood; (3304); (No price given)

The Belmont; (237); ($1,204 to $2,558)

The Berkley; (3401A, 3401B); ($1,110 to $1,435)

The Berkshire; (3374); ($1,564)

The Berwyn; (3274); ($1,249)

The Betsy Ross; (3089); ($1,412 to $1,654)

The Birmingham; (3332); (No price given)

The Bonita; (197); ($619 to $1,207)

The Branford; (3712); $2,010

The Bristol; (3370); ($2,958)

The Brookside; (2091); ($1,050 to $1,404)

The Brookwood; (3033); ($1,328)

The Bryant; (3411); (No price given)

The Calumet; (3001); ($3,073)

The Cambria; (251); ($998 to $1,771)

The Cambridge; (3289); (No price given)

The Canton; (152); ($251 to $750)

The Cape Cod; (13354A, 13354B)

The Carlin; (3031); ($1,172)

The Carlton; (3002); ($5,118)

The Carrington; (3353); (No price given)

The Carroll; (3344); (No price given)

The Carver; (3408); ($1,291)

The Castleton; (227); ($934 to $2,193)

The Cedars; (3278); ($2,334)

The Chateau; (3378); ($1,365)

The Chatham; (3396); ($1,667)

The Chelsea; (111); ($943 to $2,740)

The Chester; (3380); ($1,433 to $1,535)

The Chesterfield; (P3235); ($2,934)

The Chicora; (2031, 031) ($257 to $798)

The Claremont; (3273); ($1,437)

The Clarissa; (127); ($1,357 to $2,670)

The Cleveland; (C3233); (2,463 to $2,739)

The Clifton; (3305); ($1,660)

The Clyde; (118); ($1,397 to $2,924)

The Colchester; (3292, 3292A); ($1,988 to $2,256)

The Colebrook; (3707, 3707A); ($1,608 to $1,728)

The Collingwood; (3280); ($1,329 to $1,960)

The Columbine; (8013); ($1,971 to $2,135)

The Concord; (2021, 114, 3379); ($815 to $2,546)

The Conway; (3052A, 3052B); ($1,310 to $2,099)

The Cornell; (3226A, 3226B); ($1,360 to $1,785)

The Corning; (3357); (No price given)

The Corona; (240); ($1,537 to $3,364)

The Crafton; (3318A, 3318C, 3318D); ($916 TO $1,399)

The Cranmore; (185); ($637 to $1,283)

The Crescent; (3084, 3086); ($925 to $2,410)

The Croydon; (3718); ($1,407)

The Culver; (3322); ($873)

The Dartmouth; (3372); ($2,648 to $2,864)

The Davenport; (3346); (No price given)

The Dayton; (3407); ($1,247)

The Del Rey; (3065); ($1,978 to $2,557)

The Delevan; (2028, 028); ($285 to $949)

The Delmar; (3210); ($2,220)

The Detroit; (3336); ($1,431)

The Dexter; (3331); (No price given)

The Dover; (3262); ($1,613 to $2,311)

The Dundee; (3051); ($733 to $1,405)

The Durham; (8040); ($2,498 to $2,775)

The Edgemere; (199); ($647 to $1,124)

The Ellison; (3359); ($2,185 to $2,845)

The Ellsworth; (3341); ($1,178 to $1,236)

The Elmhurst; (3300); (No price given)

The Elmwood; (162); ($716 to $2,492)

The Elsmore; (2013); ($858 to $2,391)

The Estes; (6014); ($617 to $672)

The Fair Oaks; (3282); ($972)

The Fairfield; (No number given); (No price given)

The Fairy; (3216, 3217); ($965 to $993)

The Farnum; (6017); ($917 to $942)

The Ferndale; (3284); ($1,340 to $1,790)

The Flossmoor; (180); ($838 to $2,124)

The Fosgate; (6016); ($616 to $722)

The Franklin; (3405); ($1,118)

The Fullerton; (3205); ($1,633 to $2,294)

The Fulton; (3702); ($1,667)

The Gainsboro; (3387); ($1,475 to $1,548)

The Galewood; (3294); ($1,252)

The Garfield; (P3232); ($2,599 to $2,758)

The Gateshead; (3386); ($1,345 to $1,392)

The Gladstone; (3222); ($1,409 to $2,153)

The Glen Falls; (P3265); ($4,560 to $4,909)

The Glen View; (3381); ($3,375 to $3,718)

The Glendale; (148); ($916 to $2,188)

The Glyndon; (156); ($595 to $1,990)

The Gordon; (3356); (No price given)

The Grant; (6018); ($947 to $999)

The Greenview; (115); ($443 to $1,462)

The Hamilton; (102, 150); ($1,023 to $2,385)

The Hammond; (3347); ($1,253 to $1,408)

The Hampshire; (3364); (No price given)

The Hampton; (3208); ($1,551 to $1,681)

The Harmony; (3056, 13056); ($1,599 to $2,220)

The Hartford; (3352A, 3352B); (No price given)

The Hathaway; (3082); ($1,196 to $1,970)

The Haven; (3088); ($1,584)

The Haverhill; (3368); ($2,276 to $2,585)

The Hawthorne; (201); ($1,488 to $2,792)

The Hazelton; (172); ($780 to $2,248)

The Hillrose; (3015); ($1,553 to $3,242)

The Hillsboro; (3308); ($2,215 to $2,803)

The Hollywood; (1259, 12069); ($1,376 to $2,986)

The Homecrest; (3398); ($2,010 to $2,017)

The Homestead; (3376); ($1,319 to $1,566)

The Homeville; (3072); ($1,741 to ($1,896)

The Homewood; (P3238); ($2,610 to $2,809)

The Honor; (3071); ($2,747 to $3,278)

The Hopeland; (3036); ($2,622 to $2,914)

The Hudson; (6013, 6013A); ($495 to $659)

The Ionia; (7034, 17034); ($695 to $1,038)

The Ivanhoe; (230); ($1,663 to $2,618)

The Jeanette; (3283, 3283A); ($1.661)

The Jefferson; (3349); ($3,350)

The Jewel; (3310); (No price given)

The Josephine; (7044); ($998 to $1,464)

The Katonah; (2029, 029); ($265 to $827)

The Kendale; (3298); ($1,358)

The Kilbourne; (7013); ($2,500 to 2,780)

The Kimball; (6015); ($635 to $638)

The Kimberly; (P3261); ($1,442 to $1,815)

The Kismet; (216A, 2002); ($428 to $1,148)

The La Salle; (3243); ($2,530 to $2,746)

The Lakecrest; (3333); (No price given)

The Lakeland; (129); ($1,533 to $3,972)

The Langston; (181A, 2000); ($796 to $1,898)

The Laurel; (P3275); ($1,912)

The Lebanon; (3029); ($1,092 to $1,465)

The Lenox; (3395); ($1,164)

The Letona; (192); ($619 to $1,215)

The Lewiston; (3287, 3287A); ($1,527 to $2,037)

The Lexington; (3045); ($2,958 to $4,365)

The Lorain; (214); ($1,030 to $2,558)

The Lorne; (3053, 13053); ($1,286 to $2,002)

The Lucerne; (103); ($582 to $1,390)

The Lynn; (3716); ($1,342)

The Lynnhaven; (3309); ($2,227 to $2,393)

The Madelia; (3028); ($1,393 to $1,953)

The Magnolia; (2089); ($5,140 to $5,972)

The Malden; (3721); ($2,641)

The Manchester; (C3250); ($2,655 to $2,934)

The Mansfield; (3296); ($2,292)

The Maplewood; (3302); (No price given)

The Marina; (2024); ($1,289 to $1632)

The Marquette; (3046); ($1,862 to $2,038)

The Martha Washington; (3080); ($2,688 to $3,727)

The Matoka; (168); ($950 to $1,920)

The Mayfield; (3326); ($1,082 to $1,189)

The Maytown; (167); ($645 to $2,038)

The Maywood; (C3232); ($2,658 to $2,914)

The Medford; (3720A, 3720B); ($1,715 to $2,068)

The Melrose; (P3286); ($1,698)

The Milford; (3385); ($1,359 to $1,671)

The Millerton; (3358); (No price given)

The Milton; (210); ($1,520 to $2,491)

The Mitchell; (3263); ($1,493 to $2,143)

The Monterey; (3312); ($2,998)

The Montrose; (C3239); ($2,923 to $3,324)

The Morley; (2097); ($837)

The Mt. Vernon; (55C1910); ($851 to $1,221)

The Nantucket; (3719A, 3719B); ($1,360 to $1,536)

The Natoma; (2034, 034); ($191 to $598)

The New Haven; (3338); (No price given)

The Newark; (3285); ($2,048 to $2,678)

The Newbury; (3397); ($1,791 to $2,042)

The Newcastle; (3402); ($1,576 to $1,813)

The Niota; (161); ($788 to $1,585)

The Nipigon; (No number given); (No price given)

The Normandy; (3390); ($1,598 to $1,867)

The Norwich; (3342); ($2,952)

The Norwood; (2095); ($948 to $1,667)

The Oak Park; (3288); ($2,227 to $3,265)

The Oakdale; (149); ($1,549 to $3,067)

The Oldtown; (3383); ($1,322)

The Olivia; (7028); ($1,123 to $1,283)

The Oxford; (3393A, 3393B); ($808 to $999)

The Palmyra; (132); ($1,993 to $3,459)

The Paloma; (2035); ($688 to $1,418)

The Parkside; (3325); ($1,259)

The Pennsgrove; (3348); (No price given)

The Phoenix; (160); ($1,043 to $2,077)

The Pineola; (2098); ($489 to $659)

The Pittsburgh; (C3252); ($1,827 to $1,838)

The Plymouth; (3323); ($1,132 to $1,206)

The Portsmouth; (3413); (No price given)

The Prescott; (P3240); ($1,715 to $1,873)

The Princeton; (3204); ($3,073)

The Princeville; (173); ($810 to $1,794)

The Priscilla; (3229); ($2,998 to $3,198)

The Puritan; (3190); ($1,947 to $2,475)

The Ramsay; (6012); ($654 to $685)

The Randolph; (3297); (No price given)

The Rembrandt; (P3215A, P3215B); ($2,383 to $2,770)

The Rest; (7004); ($923 to $1,083)

The Richmond; (3360); ($1,692)

The Ridgeland; (3302); ($1,293 to $1,496)

The Riverside; (3324); ($1,200 to $1,257)

The Roanoke; (1226); ($1,784 to $1,982)

The Rochelle; (3282); ($1,170)

The Rockford; (C3251); ($2,086 to $2,278)

The Rockhurst; (3074); ($1,979 to $2,468)

The Rodessa; (7041, 3203); ($998 to $1,189)

The Roseberry; (2037); ($744 to $4,479)

The Rosita; (2036, 2043, 2044); ($314 to $875)

The Rossville; (171); ($452 to $1,096)

The Roxbury; (3340); ($1,459)

The Salem; (3211); ($2,496 to $2,634)

The San Jose; (P6268); ($2,026 to $2,138)

The Saranac; (2030, 030); ($248 to $927)

The Saratoga; (2087); ($1,468 to $3,506)

The Savoy; (2023); ($1,230 to $2,333)

The Schuyler; (3371); ($2,974)

The Seagrove; (2048); ($1,854)

The Selby; (6011); ($590 to $629)

The Sheffield; (P3266); ($2,033 to $2,098)

The Sherburne; (187); ($1,231 to $2,581)

The Sheridan; (3224); ($2,095 to $2,256)

The Sherwood; (P3279); ($2,445)

The Silverdale; (110); ($1,623)

The Solace; (3218); ($1,476 to $1,581)

The Somers; (P17008); ($1,696 to $1,778)

The Somerset; (2008); ($732 TO $1,576)

The Spaulding; (P3257); ($2,281)

The Springfield; (133); ($660 to $1,516)

The Springwood; (3078); ($1,797 to $2,089)

The Stanford; (3354A, 3354B); (No Price Given)

The Starlight; (2009); ($543 to $1,645)

The Stone Ridge; (3044); ($1,995 to $2,229)

The Stratford; (3290); ($2,122)

The Strathmore; (3306); ($1,627 to $1,757)

The Sumner; (2027, 027); ($237 to $853)

The Sunbury; (3350A, 3350B); ($1,141 to $1,237)

The Sunlight; (3221); ($1,499 to $1,620)

The Sunnydell; (3079, 3979); ($1,571 to $1,746)

The Tarryton; (C3247); ($2,967 to $2,998)

The Torrington; (3355); ($3,189)

The Trenton; (3351); (No price given)

The Uriel; (3052); ($1,374 to $1,527)

The Valley; (6000); ($904 to $989)

The Vallonia; (3049); ($1,465 to $2,479)

The Van Dorn; (P3234); ($1,576 to $2,249)

The Van Jean; (C3267A, C3267B); ($2,499 to $2,899)

The Van Page; (P3242); ($2,650)

The Verndale; (6003); ($900 to $1,130)

The Verona; (3201); ($2,461 to $4,347)

The Vinemont; (6002); ($747 to $830)

The Vinita; (6001); ($1,154 to $1,240)

The Wabash; (2003); ($507 to $1,217)

The Walton; (3050); ($2,225 to $2,489)

The Wareham; (203); ($1,089 to $2,425)

The Warren; (13703); ($1,506)

The Warrenton; (3030); ($1,288)

The Waverly; (3321); ($1,234)

The Wayne; (3210); ($1,994 to $2,121)

The Wayside; (107B, 2004); ($372 to $945)

The Webster; (3369); ($3,204)

The Wellington; (3223); ($1,760 to $1,998)

The Westly; (2026, 3085); ($926 to $2,543)

The Wexford; (3337A, 3337B); (No Price Given)

The Wheaton; (3312); ($1,235)

The Whitehall; (181); ($687 to $1,863)

The Willard; (3265); ($1,477 to $1,997)

The Wilmore; (3327); ($1,191 to $1,414)

The Windermere; (1208); ($3,410 to $3,534)

The Windsor; (3193); ($1,216 to $1,605)

The Winona; (2010A, 2010B); ($744 to $1,998)

The Winona; (C2010, C2010B); ($744 to $1,998)

The Winthrop; (P3264); ($1,921)

The Woodland; (2007); ($938 to $2,480)

The Worchester; (3291); ($2,315)

The Yates; (3711, 3711A); ($1,812 to $2,058)

105 Sears Modern Home Fact Sheets with Floor Plans.

CLICK THE FACT SHEET FOR A FULL-SIZE IMAGE.

Copyright © 2013. Sears Brands, LLC. All rights reserved.