Jean Baptiste Pointe de Sable was the founder of modern Chicago and its first negro resident. Pointe de Sable was his chosen legal name; he was never called Pointe de Sable during his lifetime. Pointe de Sable was an inseparable element of his name, which he had assumed by 1778. The prosperous farm he had at the north branch of the Chicagou River (the French spelling) from about 1784 to 1800 helped stabilize a century-old French and Indian fur-trading settlement periodically disrupted by the wars and raids of Indians and Europeans and abandoned by the French during the Revolution from 1778 to 1782.

The earliest known documents that refer specifically to him establish that in 1778 and 1779, perhaps as early as 1775, Pointe de Sable managed a trading post at the mouth of the Rivière du Chemin (Trail Creek), at present Michigan City, Indiana, not at Chicago, as is usually asserted. Pierre Durand of Detroit was associated with him and Michel Belleau in the ownership of this business. Here is Durand’s own 1784 account of Pointe de Sable’s post translated from his petition to Gen. Frederick Haldimand, then governor of Canada: “I found the waters low in the Chicagou River; I did not get to Lake Michigan until October 2, 1778. Seeing the season so far advanced that I could not reach Canada, I decided to leave my packs at the Rivière du Chemin with Pointe de Sable, a free negro, and I returned to Illinois to finish my business. On the 1st of March, 1779, I sent off two canoes to take advantage of the deep water [at Chicagou]. I gave orders to my commis [business manager] to take these two canoes to the Rivière du Chemin loaded with goods and to go ahead of me with all the men to help me pass at Chicagou . . . I met my commis [Michel Belleau] at the start of the bad part [of the portage] . . . Some days later, I arrived at the Rivière du Chemin, where I found only my packs [of furs]. The guard told me that M. Benette [Lt. William Bennett of the 8th regiment] had taken all my food, tobacco, eau de vie (brandy). A canoe to carry them . . . ” Durand also learned that this British force had taken Pointe de Sable prisoner as a suspected rebel back to Michillimackinac, which began an important phase of his career as a minor but valuable member of the British Indian Department.

Up to the time of his capture, Pointe de Sable had been an engagé in the fur trade, traveling on the Great Lakes, the Illinois River, and elsewhere from perhaps 1768 to 1779. From 1775 to 1779, his associate Durand was known to have been active in the upper country under an official trade license. Only British subjects were allowed to work in the fur trade, supervised by military officers and the governor of Quebec. All engagés and the license holder had to swear an oath of loyalty to the king before the commander at Montreal and sign a printed oath incorporated in the license. Wealthy individuals posted bonds that would be forfeited for the slightest infraction of the rules of the fur trade or acts of disloyalty. The Durand-Belleau license itself and documents of Pointe de Sable’s hiring at Michillimackinac have not been found. Pointe de Sable would have signed by making his mark since he was illiterate, as most engagés were. Still, he must have been a skilled man when Lt. Governor Sinclair hired him in 1780 for his semi-official operation at the Pinery, adjoining Fort Sinclair north of Detroit.

Once Pointe de Sable settled in Chicagou, in territory regarded by law as Indian-owned, he was mainly a farmer at the end of the Revolution. His farm was known, as far away as the nation’s capital, as the only source of farm produce in the area until after he moved away in 1800. Like all people living in the barter economy of the frontier, he traded with Indians and Europeans alike for goods and services he needed, but he was not a professional trader. William Burnett, who may already have had a financial stake in the farm during the time Pointe de Sable managed it, became the actual owner (of the buildings, not the land) after Pointe de Sable left in 1800. Burnett used it as his Chicagou trading post until his associate John Kinzie arrived in 1804. By the 1795 Treaty of Greenville, the Indians defeated at Fallen Timbers granted the United States a six-mile square tract at the river's mouth; Pointe de Sable was thus a tenant or licensee, not an owner, of the land.

The cessation of hostilities created an environment in which Pointe de Sable could prosper. He was a British subject in what was still British-controlled territory. It is generally forgotten that the Northwest Territory, ceded by Great Britain to the United States by the 1783 Treaty of Paris, was still almost completely controlled by British military forces and traders until 1796 with the implementation of Jay’s Treaty of 1794 and the surrender of military posts, such as Detroit and Michillimackinac, to the United States. However, British agents remained in place until the Treaty of Ghent ended the War of 1812 in 1815. In Chicago, the British agent was John Kinzie, who changed allegiance in 1812 at great personal risk. When Pointe de Sable sold [transferred] his improvements and household goods for 6,000 Livres in 1800 ($1,200 today), a value certified by appraisers Kinzie and Burnett, and moved to St. Charles in present Missouri. His farm in the Spanish colony of Upper Louisiana was comparable to that of prominent people in Cahokia, Illinois. There is no record that Pointe de Sable ever became an American citizen.

Pointe de Sable means “sand Pointe” in French and was probably taken as a surname by Jean Baptiste to identify a place (one of many so-named) important to him that has not yet been identified. Sable means sand. It can also mean black in the aristocratic Norman French or English heraldry, but only because this color was used to represent sand on coats of arms. Pointe de Sable is unlikely to have known this, for his command of English was rudimentary at best. Moreover, people of African descent were always called nègre in French America.

Pointe de Sable in any form is not a French surname found in any vital records of France, Canada, or the United States. In nearly all of the many surviving documents from 1779 to 1818, most of them written in French, in which Pointe was a party or was mentioned, his surname appears as Pointe de Sable. The Sieur de Sablé (without the Pointe) was a title of minor nobility used in the 18th century in the Dandonneau family of Quebec. This family had no known connection to Pointe de Sable, although the related Chaboillez family were prominent fur traders. A Haitian family named Des Sables, again lacking the Pointe, were French subjects and cannot be related to Chicago's founder, whose family probably did not even have a surname, despite the elaborate, undocumented assertions of a member of that family in a fanciful 1950 biography.

Pointe de Sable was born free, as Durand implied by calling him a “free negro.” He was the son of parents still not identified, possibly born at Vaudreuil, near Montreal, before 1750. A Jean Baptiste, nègre, native of Vaudreuil, is listed as an engagé in a 1768 fur trade license. Pointe de Sable’s mother was a free woman, not a slave. Children of slave mothers, black or Indian, were slaves under Quebec law, regardless of the father's status.

Where Pointe de Sable was before 1775 has not been reliably documented. In that year, he seems to have been hired in Montreal by Guillaume Monforton or Montforton of Detroit, a trader and notary at Michillimackinac, to travel there from Montreal. In the surviving British license papers, he is simply Baptiste, nègre; earlier licenses are similarly vague. There is no truth to the two-century-old myth that for several years from 1773 to about 1790, he farmed land at Peoria under a 1773 deed from the supposed British commander there, Jean Baptiste Maillet, and was a member of the militia in 1790. Aside from the fact that Maillet was a traveling engagé in the fur trade, under licenses from 1769 to 1776, and lived near Montreal, where he had two daughters born in 1768 and 1771, any such grant was illegal under British law. This myth was exploded in 1809 by the U.S. land commissioners hearing land claims at Peoria, who found that no purported British land grant presented to them, of which this was one, was authorized. The militia rolls for Illinois, published in 1890, have many men named Jean Baptiste, but none with a surname resembling Pointe de Sable.

In 1775, Pointe de Sable joined forces with the experienced trader Pierre Durand, a Detroit resident, and left Michillimackinac under the trade license of Michel Belleau. Jean Orillat, the wealthiest merchant in Montreal, financed and bonded his associates. They had previously been in Illinois. Orillat had been trading between Illinois and Montreal since 1767, perhaps earlier. Belleau and Durand travelled to Illinois. Belleau set up a post where Bureau Creek enters the Illinois River. Bureau is an obvious corruption of his name, most likely by local Indians whose dialect replaced the sound of 'l' with that of 'R.' For example, the Illiniwek Indians called themselves Irenioua (plural Ireniouaki). Bureau was recorded as early as 1790 as the “River of Bureau,” or at Bureau’s, which helps locate his post. Near this post was a conspicuous peninsula of sand (French, Pointee de sable), now called Hickory Ridge, behind which was a harbor providing a place to load canoes, pirogues, or batteaux. They spent some of their time in Cahokia, Peoria, and on the Illinois River from 1775 to 1779. They dealt with each other and with various local merchants such as Charles Marois (interestingly, he was illiterate), Charles Gratiot of Cahokia, Pepin & Benito, and Charles Sanguinette of St. Louis.

Pointe de Sable had an account, managed by Marois, with Michel Palmier dit Beaulieu (no relation to Belleau), a wealthy farmer and prominent Cahokia citizen. Pierre Belleau, Michel’s brother, was hired to go to Illinois in 1776 by Orillat’s former partner, Gabriel Cerré. Nothing further is known of him, but Pierre and Michel seem to have been killed by Indians along the Illinois River in the spring of 1780. Michel’s estate was administered in Cahokia, where his creditors were, although, when he went to Montreal in 1777 without Durand to get his trading license renewed, he seems to have stated that he lived in Detroit. Perhaps he and Pointe de Sable were the two young male boarders in Durand’s modest household noted in the 1779 Detroit census.

Pointe de Sable was at his trading post on the Rivière du Chemin in October 1778, when Durand, with two boatloads of furs, was forced by the lateness of the season to leave his cargo with “Baptiste Pointe Sable (a negre libre - free Negro)” instead of taking it to Montreal as he had planned. Durand had left Kaskaskia in June, just before George Rogers Clark occupied it, but was delayed by the turbulent events of the time. He eventually got underway, passing up the Illinois River and through Chicagou, reaching Lake Michigan on October 2, 1778. After leaving his furs with Pointe de Sable, Durand returned to Cahokia and Old Kaskaskia Village for the winter. Perhaps he was able to settle his and Pointe de Sable’s debts to the estate of Charles Marois, who had died recently.  |

| A trader named Guarie had built this trading cabin and farmed the land on the west side of the Guarie River [north branch of the Chicago River] as early as 1778. It's not documented when Guarie moved. Jean Baptiste Pointe de Sable established “Eschikagou ► a settlement in 1790. He lived in the Guarie cabin (unsure if he purchased it or if it was vacated) and farmed the land, raising pigs and chickens, growing corn, and trading with local Indians. |

Durand sent off Michel Belleau and two canoes of furs to the Rivière du Chemin on March 1, 1779. He remained in Cahokia and Old Kaskaskia Village to collect on his and Pointe de Sable’s accounts with Clark’s army. In July 1779, Durand stopped at Peoria, where he met his Cahokia friend Captain Godefroy de Linctot, the leader of a small army that had left Cahokia at the end of June. Lanctot had brought with him Clark’s commission of Jean Baptiste Maillet as captain of the Virginia militia (the Illinois Country was ceded by Virginia in 1778) at Peoria, a community he was expected to defend from attack. However, as Durand later told Lt. Gov. Patrick Sinclair, there was no fort there. A year later, Maillet was in St. Louis, and his clerk, Pierre Trogé or Trottier, was on the Maumee River in present Ohio. Linctot, coordinating his movements with those of Clark, was planning to attack Detroit. Major Arent Schuyler De Peyster, the British commander at Michillimackinac, got wind of this plan on July 3 and, on the 4th, dispatched Bennett overland with 20 soldiers, 60 armed traders serving in the militia, and about 200 Indians to intercept Linctot’s force, which, like Clark’s, never reached Detroit.

Durand met Belleau and 14 engagés at the start of the Chicagou portage des chênes. At Chicagou, the local Indian leaders brought him some bad news: Pointe de Sable had been at his post at the Rivière du Chemin when a detachment of Bennett’s forces under Corporal Gascon arrested him, about August 1st, confiscating 10 barrels of rum, food, clothing and a birchbark canoe with repair supplies, all worth 8,705 Livres (French: £94,756 or US: $98,766 today), all the property of Durand. Gascon took Pointe de Sable’s many packs of furs under guard to Michillimackinac, pending Durand’s expected arrival with additional packs. These would be brought by 30 horses provided by the Chicagou Potawatomi. Gascon took Pointe de Sable prisoner to Bennett, who was camped on the nearby St. Joseph River.

Bennett and De Peyster must at the least have known of Pointe de Sable because Bennett’s first report to De Peyster of his arrest, written at his St. Joseph camp on August 9, 1779, simply says, “Baptiste Pointe au Sable I have taken into custody, he hopes to make his conduct appear to you spotless,” without explaining who Pointe was or where he lived. As commandant De Peyster was responsible for keeping track of all traders in his area, Pointe could not have been a stranger to him; he was zealous in enforcing fur trade rules.

Pointe de Sable must have known some of the traders and Indians with Bennett because when he arrived at Fort Michilimackinac (a French fort and trading post, later British, at today's Mackinac Island, Michigan) about September 1st, Bennett reported to De Peyster that “the negro Pointe au Sable” had “many friends who give him a good character,” a clue to his earlier trading voyages. Pointe de Sable was married by now, but there is no mention of his family.

Pointe de Sable met De Peyster upon his arrival at Michillimackinac on September 1, 1779. De Peyster was waiting for news of glorious military exploits by troops under his command. Instead, he received Pointe de Sable’s demand that he pay for the property Bennett had confiscated from his trading post at the Rivière du Chemin. De Peyster refused to pay for these goods, valued at £580, treating them as spoils of war owned by a rebel trader. De Peyster knew he would have to reimburse Durand out of his pocket if they were not spoils of war. This was a sizable liability for an officer whose annual salary was £75. Durand was finally reimbursed in 1784, probably to De Peyster’s relief.

Shortly before De Peyster left for his new command at Detroit, Durand also arrived at Michillimackinac and learned that De Peyster had ordered his arrest. He managed to avoid being detained and wrote out an itemized bill for his property confiscated from Pointe de Sable’s post. Translated from French, the heading of the bill reads, “Memorandum of Property which I, Durand, left in the custody of Baptiste Pointe de Sable, free negro, at the Rivière du Chemin, which Mr. Bennett, commander, gave orders to seize.” De Peyster refused to pay this bill because, as he explained to Governor Haldimand when it was presented to him again in 1780, there was a rumor (not true) that Durand “had made lampoons upon the King, which were sung at the Cascaskias.” The miscreant was later identified as Jean-Marie Arsenault, dit Durand, no relation.

There is a widely accepted myth that Pointe de Sable’s farm of 1788 was not at the Rivière du Chemin, as amply documented at the time, but at Chicago. The evidence for this myth is worse than flimsy and can be briefly dealt with. Andreas, in his history of Chicago, drew upon an uncritical reading of the much later writings of De Peyster, which flatly contradicted his own and other documents from 1779 to 1784. De Peyster published a pseudo-historical narrative of his experiences at Michillimackinac in 1813 under the title of “Speech to the Western Indians” in his self-published Miscellanies by an Officer. In a fanciful recasting of the arrest of Pointe de Sable, De Peyster characterizes him as a handsome Negro, well educated, and with French sympathies. In fact, Pointe de Sable was illiterate, and in 1780 De Peyster had urged his successor Sinclair to hire him for a position at a sensitive British location. De Peyster further mangled the historical record by stating that Pointe de Sable was arrested by Capt. Charles de Langlade, not Bennett’s Corporal Gascon, and that Pointe de Sable was established at “Eschikagou ► (a settlement founded by Jean Baptiste Pointe de Sable on the north branch of the Guarie River [1], where his farm was located).” Amazingly, Andreas and every subsequent historian have swallowed these fantasies whole, although the essential contemporary documents have been available in published form for more than a century. By the time De Peyster wrote this piece of fanciful doggerel (words that are badly written or expressed), he had probably heard from old friends, like John Askin of Michillimacknac and Detroit, that Pointe de Sable was then at Chicagou (as De Peyster spelled it in his July 1, 1779 order to Langlade), and mixed up the dates. The obvious conflict between the facts and De Peyster’s late recollection of them has regrettably never been examined to discredit students of Chicago history. No credence should be given to the late jottings of a retired officer whose memory had failed him.

Pierre Durand managed to get passage on a boat manned by black sailors that took him to the Rivière du Chemin to get the 120 packs of furs he had left there in Pointe de Sable’s absence. On October 15, 1779, De Peyster left for his new command at Detroit, replacing Lt. Gov. Henry Hamilton, now a prisoner of war at Williamsburg. Shortly after De Peyster’s successor, Lt. Gov. Patrick Sinclair, assumed command at Michillimackinac, Durand arrived with his treasure of furs. Having barely survived a harrowing stormy lake voyage, the exhausted trader landed his cargo in this small leaky sailboat about October 20. Sinclair arrested him, confiscated his papers, and refused to pay Pointe de Sable's bill. Durand’s papers included a copy of Belleau’s declaration of loyalty to Virginia, a bill of exchange endorsed to Pointe de Sable, and Virginia paper money, all worthless payments for goods requisitioned from them by Clark’s rebel forces in Illinois. This convinced the erratic and generally paranoid Sinclair that Durand and Pointe de Sable were both rebels and the confiscated property was mere spoils of war. It soon became evident, however, that both were loyal British subjects who had been victimized by Clark’s impecunious Virginia forces, like many others.

Sinclair bought more trade goods from Durand on credit and promised to reimburse Durand for the cost of shipping his furs to Montreal, promises he never kept. He failed to pay Durand for moving and repairing a house for Matchekiwish, a local Chippewa war chief. He also hired a piastre (dollar) a day to guide a war party headed by Langlade to Chicagou and down the Illinois River in 1780 to join the attack on St. Louis and Cahokia. Ironically, this war party passed the post of Michel and Pierre Belleau, who were killed about this time by Indians on British orders. Sinclair had confiscated a copy of Michel’s oath of loyalty to Virginia from Durand, which became his death warrant. Durand was never paid for anything but guiding this party and the property confiscated from Pointe de Sable. Sinclair characteristically declined to pay for about 10,000 Livres of charges on Durand’s second bill.

Pointe de Sable fared much better than Durand. Surprisingly, within a year, this prisoner, arrested under suspicion of siding with the Americans, was employed with De Peyster’s knowledge and at the request of Meskiash, village chief of the local Ojibway tribe, as manager of Sinclair’s Michigan estate, the Pinery. This property, illegally bought from Indians including Meskiash and others in 1765, was near the mouth of the Pine River at present St. Clair, Michigan. He held this position from August 1780 until 1784, when the property was sold. His wife and children had probably joined him there in a house built in November and December 1779 by British workmen. This structure was built of squared pine logs covered by hand-sawed boards. The interior was partitioned into rooms, and the board walls were plastered with clay from the bed of the Pine River.

Shortly after he arrived in the Detroit area, Pointe de Sable again pressed De Peyster to pay the 8,705 Livres. De Peyster again refused because of Durand’s supposed rebel sympathies. He was taking a big risk because if, as it turned out, these goods were requisitioned from a British subject, he would be legally responsible for paying out of his own pocket. This uncertainty hung over him until the wartime expenses of the upper posts were finally approved by the auditors in London in 1787.

The Pinery was supplied from Detroit, and the commandant there was responsible for regulating this trade, including approval of any voyages there and beyond, as far as Michillimackinac. As the officer who had jurisdiction over the Pinery, De Peyster must have had regular contact with and intelligence about Pointe de Sable, who was there with his permission and no doubt was an employee of the Indian Department. One of De Peyster’s sources would have been Meskiash, the Ojibway village chief near the Pinery, who participated in a 1781 Indian council that De Peyster had convened at Detroit.

In the late summer of 1781, Pointe de Sable was apparently running a British trading post at Ouiatenon (Lafayette, Indiana). Lt. Valentine T. Dalton, the Virginia commander at Vincennes, was kidnapped from his home by Indians and taken to Quebec. In a letter to George Rogers Clark, he describes his experiences and meeting “Jno Batiste.” At the forks of the Maumee River (Defiance, Ohio), he met Pierre Trogé (“Truchey”) of Vincennes, who was running another trading post. Significantly, he mentions one of Trogé’s former employers, LeGras of Vincennes, but not Jean Baptiste Maillet, whom he must have encountered at Peoria or Cahokia.

In 1784, Pointe de Sable shipped his household goods. Obviously the furnishings of the comfortable family home of a very loyal British subject, from the Pinery to Detroit and moved there with his family. Soon he became associated with William Burnett, a wealthy and wide-ranging trader at the mouth of the St. Joseph River, who also had a post at Michillimackinac and Chicagou. By 1788, Pointe de Sable had settled with his family at the Chicago River and was farming the land with his wife and two children. He had probably disposed of the telltale framed portraits that had adorned his home at the Pinery. The subjects included King George III and Queen Charlotte Sophia; the King’s younger brother (the Duke of Gloucester); His Serene Highness, Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand, Duke of Braunschweig-Luneberg, a cousin of George III, who had sent his Brunswick troops to Canada’s defense against the rebels; and Baron Hawke and Viscount Keppel, both First Lords of the Admiralty who had battled French fleets. These treasures from their home at the Pinery would have exposed him as a loyal British subject in a place now visited by patriotic citizens and soldiers of the new United States, such as the covert intelligence officer Lt. John Armstrong, traveling under secret war department orders in 1789.

In 1788 he and Catherine went from Chicagou to Cahokia to have their marriage solemnized (formal marriage ceremony) by Father de Saint Pierre in the newly rebuilt Church of the Holy Family. Jean Baptiste had established business and personal relationships in and near Cahokia, dating back to 1778 or earlier.

In 1790 the Detroit-Cahokia trader Hugh Heward stopped at Pointe de Sable’s farm and traded cloth for food which Pointe de Sable had grown. The cloth was a major item stocked by traders, and Pointe de Sable would not have needed it if he were himself in the business.

In 1794, the legendary Shawnee war chief Blue Jacket was making plans to move out of Ohio after Gen. Anthony Wayne’s defeat of his British-backed Indian forces at Fallen Timbers, near present-day Toledo. He thought of going to “Chicagou on the Illinois River” in British-controlled territory. Still, he didn’t because the defeated Indians were forced to cede a six-mile square tract at the mouth of the Chicago River to the United States in the 1795 Treaty of Greenville. A 1794 smallpox epidemic that killed 50 Indians at Chicagou must also have discouraged him.

In 1794, Pierre Grignon, a British trader living at Green Bay, paid a visit to Pointe de Sable at Chicagou. The brief report of this meeting by his brother Augustin Grignon included a cryptic reference to a government commission Pointe de Sable exhibited to his visitor, who probably then considered himself a fellow British subject in British-controlled territory. It seems unlikely that the United States would employ Pointe de Sable as a secret agent, a man who had been a British subject working at the Pinery, a post controlled by the British Indian Department for several years. The Grignons were themselves employees of the Indian Department as late as 1815. In fact, John Kinzie, the Chicagou trader who acquired Pointe de Sable’s farm in 1803, was an officer of this department. He narrowly escaped hanging or being killed by pro-British Indians for treason committed near Detroit after he had switched his allegiance to the United States in 1812. He had been reported by Shawnee Chief Tecumseh as attempting to win Indians to the American side while bringing them gunpowder furnished by his department.

Suzanne Pointe de Sable was married at Cahokia in 1790 to Jean Baptiste Pelletier; Father Pierre Gibault, long sympathetic to the American cause, officiated. The young couple must have lived with or near her parents in Chicagou. Their daughter, Eulalie, was born there in 1796.

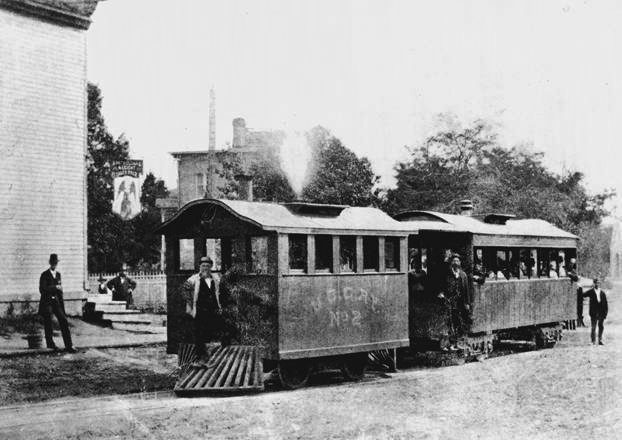

|

The Kinzie Mansion. The House in the background is that of Antoine Ouilmette.

Illustration from 1827. |

Successive owners and occupants include:

- Jean Lalime/William Burnett: 1800-1803, owner. (A careful reading of the Pointe de Sable-Lalime sales contract indicates that William Burnett was not just signing as a witness but also financing the transaction, therefore controlling ownership.)

- John Kinzie's Family: 1804-1828 (except during 1812-1816).

- Widow Leigh & Mr. Des Pins: 1812-1816.

- John Kinzie's Family: 1817-1829.

- Anson Taylor: 1829-1831 (residence and store).

- Dr. E.D. Harmon: 1831 (resident & medical practice).

- Jonathan N. Bailey: 1831 (resident and post office).

- Mark Noble, Sr.: 1831-1832.

- Judge Richard Young: 1832 (circuit court).

- Unoccupied and decaying beginning in 1832.

- Nonexistent by 1835.

In 1796, Pelletier got a receipt at Chicagou for some furs, credited to his father-in-law’s account, signed by the trader Jean Baptiste Gigon as agent for François Duquette of Michillimackinac and St. Charles. The receipt acknowledges payment of two dozen eggs to have the furs pressed and packed for shipment, a service not necessary if Pointe de Sable had a trading post equipped with the press needed to package furs. Three years earlier, Duquette, under a British trading license, had been selling trade goods below cost to the Wabash Indians in an effort to keep them loyal to the crown.

The Pelletiers and another pair of Chicagoans, the Le Mai's, went to St. Louis in 1799 to have their children baptized. Little Eulalie Pelletier, whose grandparents were not present, had two interesting godparents. Hyacinthe St. Cyr, now a prominent merchant in St. Louis, was the brother of Baptiste St. Cyr, who in 1770 had led a group of Jean Orillat’s engagés to Chiquagoux (another French name for Chicago) to evaluate it as a site for a trading post, which Orillat never established. Hyacinthe’s wife, Hélène Hebert, acted as godmother. St. Cyr would have known Pointe de Sable and may have acted as his representative at the ceremony. Hélène’s brother François had been Pointe de Sable’s fellow voyageur from Detroit to Michillimackinac in 1775.

Suzanne`s brother Jean Baptiste Pointe de Sable [Jr.], of whom little is known, was living in St. Charles before 1810. He worked for Manuel Lisa, a Spanish trader of St. Louis, as an engagé on an 1812-1813 trading expedition up the Missouri River. He died in 1814, and his father was the administrator of his meager estate. The surviving probate documents do not mention any heirs. It is not known when Catherine died. Pointe de Sable sold [transferred] his Chicago property in 1800 to his neighbor Jean Baptiste La Lime. William Burnett financed the deal, guaranteeing payment because La Lime put up no earnest money. Catherine did not sign the bill of sale, probably because she was no longer living. Jean Baptiste Pelletier may have been alive in 1815, but nothing is known of Suzanne and Eulalia at that time, nor indeed since 1799.

In the fall of 1800, Pointe de Sable moved from Chicagou to St. Charles in Spanish Upper Louisiana. There he bought a house and lot from Pierre Rondin, a free negro, and acquired two tracts of farmland. François Duquette was now his neighbor. He became involved in various real estate transactions that did not work out, including perhaps even the land he had bought for his home based on Spanish land titles of doubtful validity. In some of these deals, he was joined by his son. By 1809, he was in financial difficulties. Duquette got a judgment against Pointe de Sable for negligence in 1813, but the sheriff could not collect because Pointe de Sable was insolvent.

Somehow, Pointe de Sable’s name had become involved in the rampant land speculation of the time. Two spurious claims were made by men who had supposedly purchased his rights under acts of Congress to land in Illinois. These claims were filed by land jobbers with the U.S. Land Office at Kaskaskia about 1804, based on the fictitious assertion in perjured documents that he and his family had lived and farmed at Peoria from 1773 to after 1783 and that Pointe de Sable had served in the militia there in 1790. Of course, Pointe de Sable has been well documented as being elsewhere. In 1809, the Land Office rejected these claims as unproven. In 1815, it grudgingly and tentatively recommended that Congress consider approving these claims, but only to Pointe de Sable himself, who was probably unaware of the use of his name by swindlers. The disappointed speculator, Nicolas Jarrot, must not have told Pointe de Sable about Congress’s tentative approval in 1816; in fact, he seems to have abandoned these and several other dubious Peoria claims, and he did not mention them in his will, written in 1818, the year Pointe de Sable died. Had deeds been issued with Congressional approval, Pointe de Sable would have received title to 800 acres of valuable real estate in Peoria. But this was not to be, and his financial woes increased. No further land claims were made in his name before another land office in 1820, specifically under the law for consideration of Peoria claims, probably because they had already been exposed as fraudulent and would have been disputed by the testimony of long-time Peoria residents who recalled events well before 1779, but who did not remember the well-known Pointe de Sable.

By 1813, Pointe de Sable was destitute and had even been forced to borrow household utensils from his neighbor, Eulalie Barada. This Eulalie, who has been carelessly confused with Pointe de Sable’s granddaughter Eulalie Pelletier, was the daughter of Louis Barada (Baradat) of St. Charles, a prominent landowner, and Marie Becquet, a native of Cahokia. Eulalie was born in St. Louis, probably in 1788, and married her first husband in 1802. In 1813, Pointe de Sable deeded all his remaining property to his “friend” Eulalie, not for money, but for her promise to take care of him for the rest of his life in sickness and in health, to do his washing, provide firewood, repair his house, supply corn to feed his pigs and chickens, and to arrange for his burial in the parish cemetery. She and her second husband, Michel De Roi, both made their marks on the 1813 deed. Pointe de Sable affixed his usual “signature,” the block capitals IBPS, this time writing the S backward.

On August 28, 1818, Pointe de Sable died quietly in his sleep at the age of seventy-three. On the 29th, he was buried in the St. Charles Borromeo parish cemetery. The priest’s handwritten entry on the burial register describes him as nègre. Unlike the usual burial records of this period, there is no mention of his age, origin, parents, relatives, or people present at the ceremony. Nor is there any record of probate proceedings.

The contemporary documents, long-neglected and never assembled, tell a fascinating story of a successful free-born negro entrepreneur, advancing through a series of significant careers to a position of prominence in Chicagou and then in his final tragic years to poverty and ignominy (disgrace).

The founder of the modern city of Chicago merits nothing less than recognition of the facts of his life.

NOTE: Chicago's Michigan Avenue Bridge was officially renamed the "DuSable Bridge" in October 2010 to honor Jean Baptiste Pointe de Sable, the first negro, a non-native settler in Chicago.

|

| Michigan Avenue Bridge, Chicago |

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Contributor John F. Swenson