As early as 1832, Jews coming from Eastern Europe settled in Chicago. Many sought to escape persecution and oppression in places like Bohemia, the Russian Empire, and Austria-Hungary.

Chicago's earliest synagogue, "Kehilath Anshe Mayriv" (KAM), was founded in 1847. Fifteen years later, KAM had given birth to two splinter synagogues, the Polish-led and Orthodox-oriented "Kehilath B'nai Sholom" and the German-led and Reform-oriented "Sinai Congregation." These people spoke Hebrew, Yiddish, and Slavic languages like Russian, Polish, and Ukrainian.

|

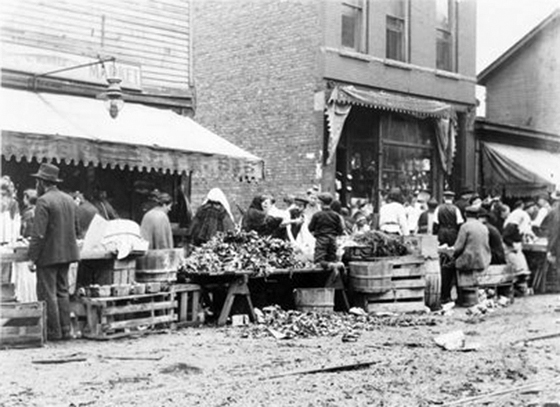

| Jewish Market on Jefferson Street near 13th Street, Chicago, Illinois, 1907. |

.jpg) |

| Jewish Market on Jefferson Street near 13th Street, Chicago, Illinois, 1907. |

Enclaves of the Jewish population formed in Northern neighborhoods such as Lakeview, Edgewater, Albany Park, and on the South Side around Halsted and Maxwell streets. At one point, 55,000 Jews lived in the Maxwell Street area alone.

sidebar

The 2020 estimate of the Chicago Jewish population is 319,600 Jewish adults and children who live in 175,800 Jewish households. An additional 100,700 non-Jewish individuals live in these households, for a total of 420,300 people in Jewish households.

From these strong roots, the Jewish community in Chicago today has grown to be the fifth-largest in the nation behind New York, Los Angeles, Miami, and the San Francisco Bay Area, and number seven worldwide.

Many decided to open businesses to serve their communities during this influx of Jewish immigrants. These entrepreneurs started to produce classic Ashkenazi Jewish food from Central and Eastern Europe, like the bagel and the bialy, and to sell it in a traditional delicatessen setting—the deli.

Now a hallmark of the patchwork of American culture, delis are famous for their oniony, peppery flavors and served awesome lox, corned beef, pastrami, gefilte fish, kishkes, whitefish salad, rye bread, and bagels . . . the list goes on and on! Aside from the food, they are beloved nationwide for their counter service and commitment to quality.

Over the years, several famous delis in the Chicagoland area brought this excellent food to Chicagoans for years. While not all of them remain open today, a few greats include Leavitt's Delicatessen on Maxwell Street, The Bagel Nosh on State Street in the Rush Street area, Ashkenaz Deli in Rogers Park, D. B. Kaplan's in the Gold Coast, Mrs. Levy's Deli in the Loop, Manny's Restaurant and Delicatessen in the South Loop, Kaufman's Deli in Skokie, Fanny's Deli in Lincolnwood, and Morry's Delicatessen in Hyde Park.

There indeed used to be more delis in Chicago than there are now. Why are the numbers of this classic institution dwindling? There's no one answer—operating costs are high, tastes are changing, and the older patrons are shrinking and moving. However, the enthusiasm for this type of food is far from gone. New concepts and ideas are circulating, and with things like the slow food movement, the focus is returning to traditional methods and quality ingredients (some authentic imports).

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

#Jewish #JewishThemed #JewishLife