Royal Jewelers & Loans (Royal Pawn Shop) is a pawn brokerage group located in Illinois that has three pawnshop locations: two pawn shops in Chicago; A-Royal Pawn Shop 428 S. Clark Street, Chicago, Just Pawn, Inc., 4509 N. Sheridan Rd., Chicago, and A-1 American Jewelers & Pawns, 6151 W. North Ave., Oak Park, Illinois.

They are one of the largest and oldest pawn and gold buying businesses. Their family has been in the business for over 100 years. Royal Jewelers & Loans offers customers the opportunity to sell their valuables or use them as collateral for a confidential loan.

"We’re not only pawnbrokers, we’re lunatics,” Wayne Cohen said about himself and his brother Randy. “We know how to handle lunatics. This is the craziest shop in the country.” The stars of the new truTV cable show “Hardcore Pawn: Chicago,” is filmed at Royal Pawn Shop, 428 S. Clark Street, in the Loop. “My brother, my dad, my grandfather—we go back three generations. When you say, ‘pawnshop Chicago’, everybody knows the Cohens.”

The truTV Network show lasted only 8 months from January 2013 to August 2013.

RANDY COHEN

Randy Cohen, co-owner of Royal Pawn Shop with his older brother, Wayne, worked at his father's pawnshop since the age of 5 and only took time out during his early 20s to work as a bouncer at some of Chicago's hottest nightclubs. Randy says that being a bouncer taught him how to deal with any situation before it turns nasty. Of course, his 20-inch biceps also help. Randy is a hard-line rationalist always concerned about the bottom dollar. He would say he is the backbone and workhorse of Royal Pawn and that Wayne is a slacker and a dreamer. "Without me, my brother would turn a large fortune into a small one very quickly," he says. "This pawn shop would be driven into the ground." In addition to his duties at the store, Randy is an avid weight lifter, boater, and collector of firearms and cars.

WAYNE COHEN

Royal Pawn Shop co-owner and older brother Wayne jokes that he was conceived in the backroom of one of his father's old pawn shops and has worked in the family business ever since. Wayne and his brother, Randy, don't always see eye-to-eye. While many people call Wayne "the pawnbroker with a heart of gold," Randy would say that Wayne is nothing more than a sucker for a sob story. Wayne loves to take chances in the hopes that he'll get a big payday, and he admits that sometimes you win and sometimes you lose. Wayne has been married to his wife, Audrey, for 34 years. Playing basketball is one of Wayne's favorite pastimes. He says he used to play regularly with President Barack Obama (then a Senator from Illinois) and current United States Secretary of Education Arne Duncan.

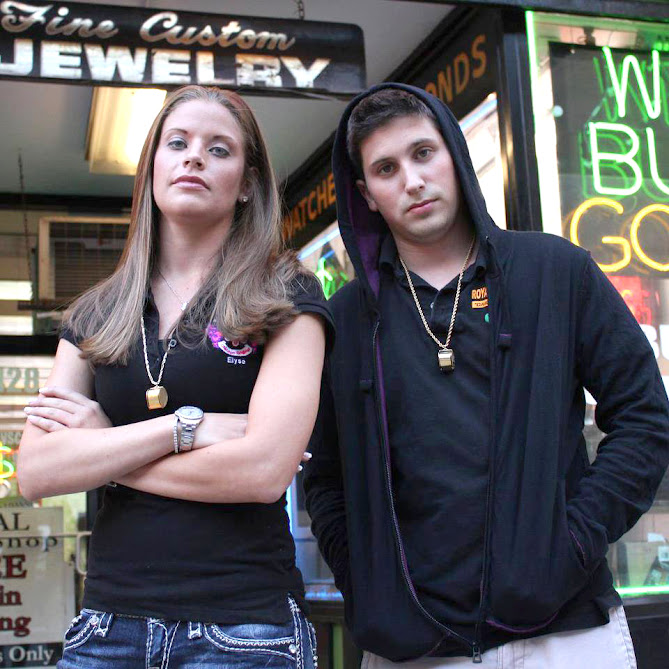

ELYSE COHEN

Elyse is Randy's daughter. She practically grew up in Royal Pawn Shop and has been working there her entire life. Elyse does it all at the store, from appraising jewelry to making loans to bossing people around. Her forte is knowing how much modern gadgets like cell phones and computers are worth, which makes her an invaluable asset to the store. While she doesn't always agree with her Uncle Wayne, she considers her dad to be her best friend, and she always has his back in the store. Elyse is not above using her close relationship with her father to her own advantage. Randy says of his daughter, "Elyse is our best customer who never pays." Elyse is as smart as she is cute. She graduated with honors from DePaul University with a bachelor's degree in business administration and a minor in Spanish. She has three Pomeranians – Paris, Jake, and Spike –she calls "her kids." She also has a substantial collection of guns, which she regularly tests out at one of the local shooting range.

NATE COHEN

Nate is Wayne's son, but he doesn't always agree with his dad. Nate has been working at Royal Pawn Shop his entire life. He is currently attending college, but he hasn't chosen a major yet. At Royal Pawn Shop, Nate writes up loans and tries to make sure no one does anything stupid. He knows the pawn business and has no time for fools. Nate is a superb tennis player and golfer and loves to spend his free time driving around in his sports car.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.