Meanwhile, crews planned to brace the southeast leaf of the span, one of four comprising the Bridge, to ensure it was stable enough to allow removal of debris.

The southeast leaf sprung open unexpectedly Sunday afternoon, sending a construction crane plummeting to the street and slightly injuring six people. The crane crashed through Michigan Avenue to Lower Michigan. The span rose so violently that it ripped off its structural mounts and twisted down and back into a concrete counterweight pit.

|

| The Raised South Leaf of the Michigan Avenue Bridge in Chicago. |

The Bridge has been undergoing a two-year reconstruction in a $31 million ($58 million today) project was scheduled for completion by late November. The southeast leaf was the last segment to be renewed.

Because of the work on the leaf and removal of some heavy steel, it has become unbalanced, officials said. But it was unknown how it became unlocked, permitting it to spring up.

Officials said a section of nearby Wacker Drive from Wabash to Stetson Avenues that was closed after the accident could reopen on Tuesday.

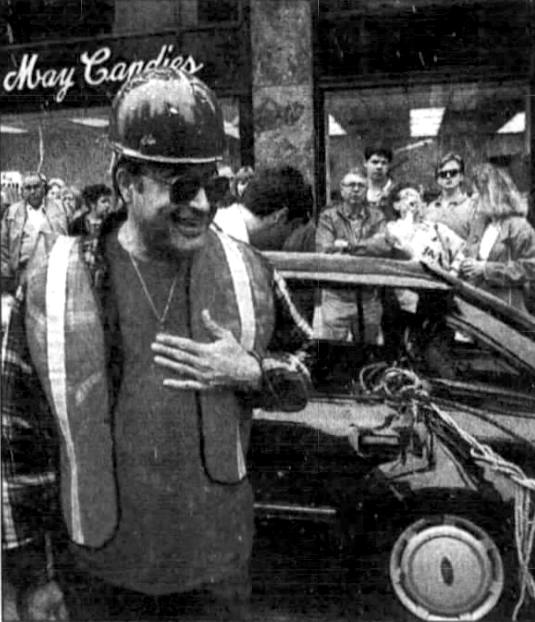

Jesus Lopez escaped serious injury Sunday when a leaf of the Michigan Avenue bridge suddenly sprang up, causing a 70-foot crane to come crashing to the street, damaging his car and others, and injuring six people.

"We were waiting for the bridge to come down so we could go back to work," said Lopez, a bridge maintenance worker. Lopez was parked on the south side of Wacker Drive, sitting in the driver's seat of his Ford Escort, when the southeast leaf of the Bridge unexpectedly rose, and the crane sitting on the Bridge came barreling down. Its cab became wedged in the gap between Wacker Drive and the Bridge. The boom, the crane's moveable post, toppled across Wacker Drive. Two traffic light poles, a crossing gate, and a Chicago police patrol car were damaged.

The huge iron ball and hook attachment to the end of the cable that runs along the boom bounced off the asphalt of Wacker Drive, leaving about a 4-inch crater and smashing through the rear driver's side window of Lopez's car, mangling the door, roof, read quarter panel and back seat.

"I guess I was just lucky," Lopez said, patting a silver cross that hung from his neck and trying to catch his breath. "I'm glad I wasn't sitting in the back seat."

The six who were injured were passengers on a CTA bus. All of them were treated for "bumps and bruises" at area hospitals and released. According to police, Michigan Avenue from Randolph Street to Ohio Street was closed to vehicle traffic.

The accident led to an acknowledgment on the part of the city that none of its inspectors had the experience or training to determine the proper balancing of weight on a bridge under construction.

The contracting team working on the Michigan Avenue bridge during the freak accident bears full responsibility for the costly mishap, experts hired by the city. The investigators exonerated the city bridgetender on the scene when the span's southeast section suddenly flew open. And on December 3, 1992, Chicago Transportation Commissioner J.F. Boyle Jr. asserted the man was "absolutely blameless."

The unnamed employee, a 12-year veteran, insisted to investigators that he did not activate the switch that normally operates a lock on the 1,700-ton bridge section. But even if he hit the switch inadvertently, the contractors were supposed to have disconnected it.

The three unsafe conditions were found by engineers included:

- Two locks-6 1/2-inch thick steel bars located under the rear of the leaf and designed to secure it in the "down" position were bent instead of straight, robbing them of strength.

- Motors that engage and disengage the locks were left fully operational.

- Electrical circuitry connecting lock motors with controls in the bridgetender's tower was fully connected, while safety features were bypassed.

Though the "unsafe construction procedures" set the stage for the accident, it had not been determined what actually triggered the Bridge's release. Possibilities include a structural failure of the rear locks or a mechanical or electrical disengagement of the locks. For the bridgetender to fully disengage the locks, he would have had to press control for eight seconds.

The investigation had gone to the point where they could go no further.

sidebar

The Michigan Avenue Bridge was renamed the "Du Sable Bridge" in October of 2010 to honor the "Father of Chicago," Jean Baptiste Pointe de Sable (the "du" of Pointe de Sable is a misnomer. It is an American corruption of "de" as pronounced in French. "Jean Baptiste Point du Sable" first appears long after his death) a French Haitian and the city's first non-native settler.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.