On June 26, 1928, Chicago labor racketeer Timothy D. Murphy, “Big Tim” (May 23, 1885-June 26, 1928), was shot to death at his Bungalow at 2525 West Morse Avenue in Chicago's Rogers Park community. Murphy was a Chicago mobster, labor racketeer, and U.S. mail thief who controlled several major railroads, laundry and dye workers' unions during the 1910s and early 1920s.

|

| 2525 West Morse Avenue, Rogers Park Community, Chicago, Illinois. |

Timothy Murphy grew up in the Back of the Yards neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side. He was a towering 6' 3," slab-bodied and mostly genial boy who later boasted of selling newspapers to the famous meatpacker Jonathan Ogden Armour outside of the main offices of Armour & Company at 43rd Street and Racine Avenue. When he was older, Murphy got a job as a railroad switchman for the Chicago junction line, which would give him lifelong sympathy for the working man's plight.

Murphy was a devoted family man and had many friends. He was regarded as a great pal to just about everyone, but his dual nature made him dangerous when provoked. All the good work that he might have accomplished in labor organizing and politics was sabotaged by his associations with criminals and hoodlums ─ and by his own dabbling in crime. In 1909, he became involved with Mount Tennes, the so-called “Telegraph Gambling King” of Chicago. Tennes set up his first telegraph switchboard in a train station in Forest Park and received race results from tracks in Illinois, Kentucky and New York. Tennes had an illegal monopoly on the information. For a share of the profits, his operators sent the results to hundreds of bookie joints, gambling parlors and pool halls all over the city. Murphy’s alliance with Tennes earned him a huge amount of money but two years later, he sold Tennes out to a grand jury and walked away without a blemish on his record.

While working with Tennes, Murphy had learned the art of bribing public officials and decided to try out politics. In 1915, he ran a highly successful campaign for the state legislature, getting elected from the working-class, Irish-Catholic Fourth Ward. He used the clever slogan “Elect Big Tim Murphy ─ He’s a Cousin of Mine!” Murphy spent just one term in Springfield, returned to Chicago, and got involved in the labor rackets.

Through his friend, Maurice “Mossie” Enright, an organizer with the American Federation of Labor and a convicted murderer, he was able to organize gas station attendants, garbage collectors, and then street sweepers. Strikes, wage increases, and higher union dues followed, and Murphy got a percentage of everything. He and Enright operated from Old Quincy No. 9, a famous saloon at Randolph and LaSalle Streets, and for a time, the two men were inseparable. Eventually, the two men had a falling out over the division of proceeds from the settlement of a labor strike, and their friendship came to an end. Like Mount Tennes years before, Enright was blindsided by Murphy’s ruthless ambition.

On February 3, 1920, Enright was getting out of his car in front of his home on Garfield Boulevard when five men in another automobile pulled up and opened fire on him before he could draw his own revolver and defend himself. Enright was hit 11 times and was dead when the other car pulled away. His wife found him moments later, lying in a pool of his own blood. Tim Murphy, Michael Carozzo, the head of the Street Sweeper’s Union, and several others were arrested and questioned about the murder, but each man had an alibi and was let go.

You’re likely not surprised to learn that Enright’s murder still remains unsolved.

Murphy continued to run the three unions but was too restless and greedy to be happy with the small amount of money that was coming in. In 1920, he organized his first mail robbery. It went off without a hitch, understated and bloodless, and occurred after informants told Murphy about an overheard telephone conversation concerning money coming into the Pullman station. Two bags of cash that amounted to just over $125,000 were sent by insured, registered mail and arrived at the Illinois Central Station in Pullman on August 30. When the train pulled in, a bank messenger named Minsch was waiting on the platform. He signed for the sacks and tossed them onto a mail chute. Three boys with a cart earned a quarter each from Minsch by loading whatever he sent down the chute into his car. The boys were waiting but had trouble lifting the two bags. Two men were standing nearby, apparently waiting for someone, and saw the boys and walked over to help. The boys directed the men to take the bags to Minsch’s car, but they kept walking, tossed the two bags into the backseat of another car, and drove away. One of the men was Big Tim Murphy, and the other was his partner, Vincent Cosmano.

Unfortunately for Murphy, someone talked, and the two men were arrested and indicted by a grand jury. Murphy needed money for lawyers, so he decided to rob another train to get it. |

| (L-R) Tim Murphy, Fred Mader, John Miller, and Cornelius Shea during their murder trial in 1922. |

This time, he bribed a mail clerk in Indianapolis for a tip on a weekly shipment of cash and government Liberty Bonds that was sent to the Federal Reserve in Chicago. Murphy put together a crew (which included Cosmano, his long-time driver, Ed Guerin, Mike Carozzo, and two brothers, Frank and Pete Gusenberg), and they set up surveillance on the Dearborn Station at Polk Street. After they learned when the money shipment arrived, they pulled off the robbery on April 6. They escaped in a stolen Cadillac with $380,000 ($5,735,000 today).

It didn’t take long for the police to get suspicious, and the mail clerk that Murphy had bribed was the first to confess. Ed Guerin also talked because Murphy never gave him his share of the money. A judge issued a search warrant for the house where Murphy’s father-in-law lived, and postal inspectors found a trunk in the attic that was so heavy with cash and bonds that it took four men to haul it out. The bills in the trunk were brand new, and the Federal Reserve had a list of their serial numbers. The money, plus the two confessions, sent Murphy to Leavenworth for four years.

|

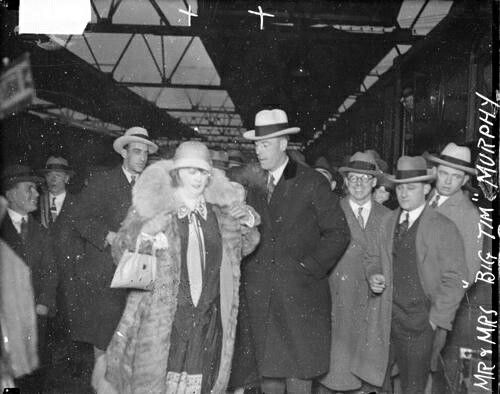

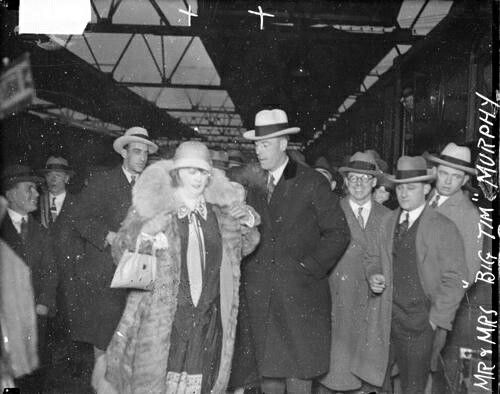

| Big Tim Murphy and His Wife, Phyllis, in 1926. |

Murphy was washed up when he was released from prison. But he was an eternal optimist and began devising new schemes to make money while his long-suffering wife, Florence, pestered him to find a suitable line of work.

Murphy wasn’t interested. There was too much money to be made as a criminal. He began cooking up a series of hare-brained schemes, including a banana plantation in Texas, a portable grocery store on wheels, a dog track, a travel agency, and even a plan to manufacture stop-and-go traffic lights. The latter was an idea ahead of its time, but no one was interested in what Big Tim was selling. He finally realized that the union dues of the rank and file, not his get-rich-quick schemes, made money, and he decided to take up where he had left off with labor organizing. He tried organizing tire dealers, jelly manufacturers, gasoline dealers, and garage workers, but none of them worked out.

Finally, he hatched a plan to take over the Cleaners and Dyers Union, a union with 10,000 members that was already controlled by Al Capone. Murphy stormed into the business office of the union on South Ashland Avenue with a gunman at his side and announced a “hostile takeover.” They surrendered.

Murphy’s attempt to take over a union run by Al Capone was the last mistake he ever made.

On the evening of June 26, 1928, Murphy was spending a quiet night at home in the West Rogers Park neighborhood on the far North Side. His wife was away at a church festival, and he was listening to the 1928 Democratic National Convention on the radio with his brothers-in-law, Harry and William Diggs. Around 11:00 pm., someone knocked loudly on the front door. Instead of going to the door, Murphy and Harry Diggs slipped out the side door and went around the house to see who was there. When they saw no one, Murphy walked across the front of the house and onto the lawn. Just then, gunfire broke out from a sedan that was parked on the street, and Murphy was shot down in the yard. As the car sped away, the Diggs brothers spotted four men inside, although none of them were ever identified.

Murphy was carried into the house, and as he lay dying, he tried desperately to say something to his brothers-in-law but died before he could speak. The police arrived before Florence returned from church. When she found her husband’s bloody body lying on the living floor, she collapsed on top of him and began to weep. She promised revenge: “If I knew who had killed Tim Murphy, I wouldn’t tell anybody ─ I wouldn’t wait for anybody. I’d take a gun and kill them as they killed him.”

Big Tim Murphy was laid to rest at Holy Sepulchre Cemetery, Alsip, Illinois, and unlike the gaudy gangster funerals of the 1920s, only a modest crowd attended the service. No gangland officials or politicians were at the service, although a few South Side and Back of the Yards characters did turn out for the wake the night before the burial. Too much had changed while Murphy had been in prison, and his hold on the Chicago rackets had slipped away in his absence. He was not a man anyone wanted to get close to, and even the tags on the funeral flowers were removed so that no outsider could know who sent them. The Catholic Church refused every form of funeral service, so an old friend who was an undertaker on the South Side recited the Lord’s Prayer, the only words spoken over his body.

It was a sad end to a man who started out with a lot of potential but greed and a failure to realize when ambition had gone too far finally cost him his life.

Ninety-five years after the shooting that claimed Big Tim's life, the bullet holes from that violent summer night are still visible in the yellow bricks of the bungalow where he once lived. They serve as the visible reminder of a man who never achieved fame in the annals of Chicago crime but left a bloody mark on it nonetheless. His murder was never solved.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.