THE CHICAGO, AURORA & ELGIN RAILROAD -

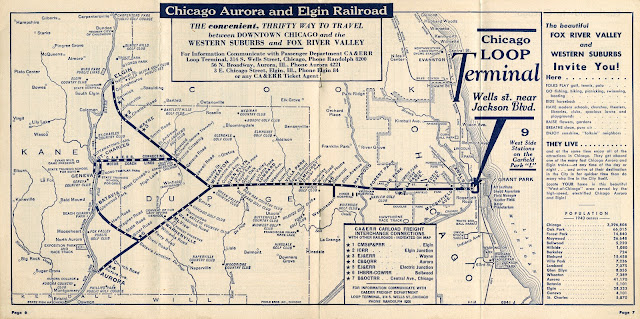

The Chicago Aurora and Elgin Railroad (CA&E), popularly known as the "Roarin' Elgin" or the "Great Third Rail", was an interurban railroad that operated passenger and freight service on its line between Chicago, Illinois and the western suburban towns of Aurora, Batavia, Geneva, St. Charles, and Elgin. The CA&E connected directly with the Chicago Elevated (Metropolitan West Side Elevated Railway.) and the cars operated over the 'L' to provide a one seat ride into the center of Chicago's downtown Loop.

The Chicago Aurora and Elgin Railroad (CA&E), popularly known as the "Roarin' Elgin" or the "Great Third Rail", was an interurban railroad that operated passenger and freight service on its line between Chicago, Illinois and the western suburban towns of Aurora, Batavia, Geneva, St. Charles, and Elgin. The CA&E connected directly with the Chicago Elevated (Metropolitan West Side Elevated Railway.) and the cars operated over the 'L' to provide a one seat ride into the center of Chicago's downtown Loop.

The line proved to be very popular during the buildup of suburban living in the Western suburbs of Chicago, and was always short of equipment to provide a sufficient level of service. Throughout its entire history the line never retired a single car until it ceased operating.

With vehicular traffic still increasing on the eve of World War II the CA&E ordered 10 new interurban cars from St. Louis Car Company in 1941 but they were held up by the shortages created by the war. Once the war ended the cars were built and delivered in the fall of 1945. While these cars incorporated some more modern features available in equipment built in the post war era they had to be able to operate with the railroads older equipment, and this precluded any radical designs. Most historians view these cars as the last traditional interurban cars built in the United States.

In the early 1950's the State of Illinois decided to start construction on the long planned Congress St. Expressway on the right of way of the L and the CA&E and required the removal of the 'L' structure used by the CTA and CA&E. While the CTA continued to provide service via a grade-level temporary alignment, the CA&E chose to cut back to Desplaines Avenue in Forest Park. The loss of the one-seat ride placed the CA&E line at a severe disadvantage. Wounded by this and the increased use of automobiles during the 1950's the CA&E quite abruptly ended passenger service in 1957.

Freight service was suspended in 1959, and the railroad was officially abandoned in 1961. The railroad was finally liquidated in 1962.

Freight service was suspended in 1959, and the railroad was officially abandoned in 1961. The railroad was finally liquidated in 1962.

IN THE BEGINNING (1899–1901)

The first known attempt to create an electric railway between the metropolis of Chicago and the Fox Valley settlement of Aurora was in late 1891. By this time, passengers in Aurora and Elgin were served by steam engines. Elgin was served by the Milwaukee Road. Geneva and West Chicago served by the Chicago and North Western Railway. St. Charles served by The Chicago and Great Western. And, Aurora was served by the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy (CB&Q). However, it was thought that an electric line would greatly facilitate interurban travel, as there would be no freight trains to slow passenger trains. A group of investors founded the Chicago & Aurora Interurban Railway with a $1 million investment. However, the railroad was unable to secure additional funds; it failed to meet an 1893 construction deadline and effectively ceased operation thereafter.

A second attempt came two years later with the Chicago, Elgin & Aurora Electric Railway. Plans called for the railroad to run through Turner (now West Chicago), Wheaton, and Glen Ellyn. Like its predecessor, the railroad failed to acquire the necessary funds for construction. Yet another group incorporated the DuPage Interurban Electric Railway in 1897, but was met with a similar fate. Small electric lines opened in the 1890s that connected the municipalities of the Fox River Valley. A profitable streetcar railway stretched from Aurora north to Carpentersville. The success of this railway inspired investors to again attempt an electric connection to Chicago. A group led by F. Mahler, E. W. Moore, Henry A. Everett, Edward Dickinson, and Elmer Barrett formed independent railway lines that were projected to stretch from Aurora and Elgin to Chicago. These two companies were incorporated on February 24, 1899. The Everett-Moore group was Ohio's largest interurban railroad company and had experience administrating several lines around Cleveland, most notably the Lake Shore Electric Railway. These two companies, the Aurora, Wheaton & Chicago Railway and Elgin & Chicago Railway, were incorporated on February 24, 1899.

Only one day after their founding, a second group of Cleveland-based investors, led by the Pomeroy-Mandelbaum group, incorporated the Aurora, Wheaton, & Chicago Railroad Company. Pomeroy-Mandelbaum was the second largest interurban railway company in Ohio and intended to compete against the Everett-Moore group. A meeting between the Everett-Moore syndicate and Pomeroy-Mandelbaum group occurred in either 1900 or 1901 to discuss the future of the two companies. They came to an agreement: Everett-Moore would build and maintain the railways connecting Aurora to Chicago while the Pomeroy-Mandelbaum group would control railways linking cities in the Fox River Valley (eventually consolidating as the Aurora, Elgin and Fox River Electric Company [AE&FRE]). A third railway, the Batavia & Eastern Railway Company, was incorporated by the Everett-Moore group in 1901 to link the town of Batavia to the Aurora line. On March 12, 1901, all of the previously incorporated Everett-Moore companies were merged into one, renamed the Aurora, Elgin & Chicago Railway Company (AE&C). Three million dollars' worth of bonds were issued in 1901 to support track construction.

CONSTRUCTION (1901–1902)

Construction commenced on September 18, 1900, when the AE&C started to grade its right-of-way. The AE&C received permission to cross existing track lines in February 1902, alleviating one of the largest obstacles in the railway's construction. Construction escalated following the winter months; by April, the third rail had been completed between Aurora and Wheaton. Later that month, the railway connected to the Metropolitan West Side Elevated Railroad at 52nd Avenue (modern day Laramie Avenue) in Chicago. The company operated steam locomotives on completed portions to deliver construction goods to where they were needed. Wheaton was selected as the site of the railroad's headquarters, car barn, and machine shop. $1.5 million in preferred stock was issued in April 1902 to cover unexpected costs.

AE&C purchased a 28-acre lot south of Batavia and constructed a power station to provide electricity. Commercial electric power was not yet available at the time, so the railroad needed to provide its own power for the third rail. Steam boilers were fed with coal provided by the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad. On April 11, 1902, they signed a contract with General Electric to provide electrical generators, transformers, and converters for the powerhouse. The line completed a network of utility poles through the right-of-way, allowing communication and power exchange between electrical substations along the track in Aurora, Warrenville, and Lombard. A fifth station was built southeast of Wayne for the Elgin branch. The substations converted the alternating current in the power lines to a lower-voltage direct current for use in the third rail. After its completion, the power station also provided power for at least three small trolley lines and several Fox Valley communities.

The Cleveland Construction Company was hired to build the line. All three rails were traditional "T" design rails laid on stone ballast. Wooden railroad ties were laid 2,816 ties to the mile and separated at standard gauge. Every fifth tie was 9 feet long to support the third rail. The majority of the line was a double track, with a single track running from the Chicago Golf Club to Aurora. Roadbeds for the double track were 30 feet wide and were surrounded by woven wire fencing. The third rail was usually placed on the inner sides of the double track, providing safety for residents and employees. The third rail was interrupted at railroad crossings, where a cable was placed underground to carry the current across the 75-foot gap.

The first inspection trip of the 34.5-mile line was held on May 16, 1902. The train departed from 52nd Avenue to Aurora, then traversed the AE&FRE south to Yorkville then north to Dundee. AE&C management announced later that evening that they planned on opening the line on July 1. The AE&FRE announced soon afterward that it would offer express transfer service from Fox Valley communities to the AE&C. On May 17, the AE&C tested the powerhouse in Batavia and found several problems with its performance. Heavy rains in June stalled construction and washed out some completed roadbed. The opening date was pushed to July 12, but delays in rolling stock production further stalled it to August.

Poor investments forced the Everett-Moore syndicate to sell its shares in the AE&C in mid-1902. The company had formed a telephone company, but struggled to compete with the Bell Telephone Company. In addition, one of their construction companies went bankrupt, spurring a credit crisis in Cleveland. Creditors demanded pay, and the Everett-Moore group sold off several assets, including their shares of the railroad company totaling $200,000. The Pomeroy-Mandelbaum group still held a large share in the company and became leaders in its operation.

The G. C. Kuhlman Car Company was tasked with providing thirty passenger cars but, for unknown reasons, the deal fell through. An order was placed with the Niles Car and Manufacturing Company in March 1902 for ten cars. Niles Cars were in such high demand that the company was unable to fulfill the full order, but did deliver the AE&C's first six cars on July 29, 1902. The cars were 74,325 pounds with four 125 horsepower motors and 36-inch wheels. They were described as "miniature Pullmans" and could seat forty-six or fifty-two passengers. Another twenty cars were ordered from the John Stephenson Car Company and would arrive after the railway was opened.

Car 10 during an inspection on August 4, 1902. The first ten cars were assigned even numbers from 10 to 28. One final problem for the AE&C was finding enough qualified motormen to run the trains. The company found none in the immediate area and had to recruit sixteen men from Dayton, Ohio. Another inspection tour occurred on August 4, from Wheaton to 52nd Avenue. A Niles Car was pulled by a steam locomotive along the track to ensure that none of the curves were too sharp for the intended rolling stock. Original plans called for the third rail to guide the car, but the company experienced many electrical problems along its power lines. By the time the third rail was functioning properly, two hundred and fifty utility poles had burned to the ground due to faulty insulators. A final inspection took place on August 21 from Wheaton to Elmhurst. Although problems with the utility poles were noted, the inspection was otherwise considered a success. For the next three days, engineers tested the line from Aurora to Wheaton so that they would have a familiarity with the track.

Despite a malfunctioning power system, a group of nearly-untrained motormen, and only six pieces of operational rolling stock, the Aurora branch of the Chicago Aurora and Elgin Railroad opened on August 25, 1902. Fares were 25 cents one-way and 45 cents round-trip. Passengers who wanted to enter The Loop had to transfer to the Metropolitan West Side Elevated at 52nd Avenue for an additional five cents. Service began at 5:33am and concluded at 11:33pm, with trains running every thirty minutes. Terminals were opened to the public at 52nd Avenue, Austin Avenue (in Chicago), Oak Park, Harlem Avenue (in Forest Park), Maywood, Bellwood, Wolf Road (in Hillside), Secker Road (in Villa Park), South Elmhurst, Lombard, Glen Ellyn, College Avenue (in Wheaton), Wheaton, Gary Road (in Wheaton), Chicago Golf Grounds, Warrenville, Ferry Road (in Warrenville), Eola Junction (in Aurora), and Aurora.

A one-way trip from Aurora to Chicago was seventy-five minutes. The final four cars from the Niles Car Company arrived on September 5 and were put into service seven days later. The original train schedules posted at stations showed service on the Batavia branch. However, actual service did not begin until the last week of September 1902. The Batavia branch met the Aurora branch at Eola Junction. Even when opened, the Batavia branch experienced little traffic and may have been primarily used as convenient transport for railroad officials to the Batavia powerhouse.

The AE&C issued promotional leaflets to citizens of Fox Valley cities and towns. They also sent these pamphlets to settlements west of Aurora, hoping that people would take a steam train to Aurora and then transfer to the electric line. They boasted that the AE&C was the "finest electric railroad in the world." By the end of the year, the AE&C was seeing monthly earnings in excess of $16,500. In addition, the nearby Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad had a dramatic decrease of passengers between Aurora and Chicago.

The twenty cars from Stephenson arrived in December 1902. Fifteen cars were equipped with motors (even numbers 30–58) and five did not (odd numbers 101–109); these latter five cars were intended to only be used as trailing cars. Trailing cars would often be added or removed at Wheaton depending on the number of passengers. The Stephenson cars were almost identical in every respect to the Niles cars. These new cars reduced the travel time between Aurora and Chicago to one hour. The new cars also allowed the railroad to operate at faster speeds—one run from 52nd Avenue to Aurora averaged 65 miles per hour.

Service to Elgin began on May 26, 1903. The 17.5-mile branch split off from the main line at Wheaton, and allowed trains from Chicago to reach the Fox Valley city in sixty-five minutes. When opened, the AE&C was able to change its schedules to allow trains to leave 52nd Avenue every fifteen minutes, alternating between Aurora and Elgin. All trains at this point ran locally, stopping at every station. The AE&C briefly considered expanding to Mendota in late 1903, but determined that it was not worth the financial risk. Though cars primarily carried passengers, some early morning cars carried light freight. Notably, the AE&C reached a deal with the Chicago Record Herald in October 1903 to distribute the paper to the suburbs along the line.

By 1910, the railroad had added a branch from near Wheaton to Geneva and St. Charles. Most of the interurban's lines used a third rail for power collection, which was relatively unusual for interurban railroads. While third rail had become the standard for urban elevated railroad and subway systems, most interurban railroads used trolley poles to pick up power from overhead wire; the AE&C only used trolley wire where necessary, such as in the few locations where the interurban had street running.

Originally, the railroad's Chicago terminus was the 52nd Avenue station that it shared with the Garfield Park elevated railroad line of the Metropolitan West Side Elevated Railroad, and where passengers transferred between interurban and elevated trains. Beginning on March 11, 1905, the interurban began operating over the Metropolitan's "L" tracks, allowing AE&C trains to directly serve downtown Chicago. At the same time, the Metropolitan's Garfield Park service was extended west of 52nd Avenue, replacing the AE&C as the provider of local service over the interurban's surface-level trackage as far west as Desplaines Avenue in Forest Park. The interurban's trains terminated at the stub-ended Wells Street Terminal, adjacent to the Loop elevated. The interurban continued to use the "L" tracks through the years of Chicago Rapid Transit Company (CRT) ownership and into the Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) era.

THE CHICAGO AURORA & ELGIN RAILROAD

World War I was tough for the AE&C, and the railroad entered bankruptcy in 1919. Having shed the Fox River Lines (an interurban which paralleled the Fox River), the reorganized company emerged from bankruptcy as the Chicago Aurora and Elgin Railroad on July 1, 1922, under the management of Dr. Thomas Conway, Jr..

A branch from Bellwood to Westchester was built in the 1920s. CRT's elevated train service was extended onto the branch in 1926; the "L" company was the sole provider of passenger service on the branch and this new service replaced the CA&E's own local service on its main line east of Bellwood.

Utilities magnate Samuel Insull gained control of the CA&E in 1926. Insull and his corporate interests had already taken over and improved the properties of the North Shore and South Shore Lines.

Insull's plans to make similar improvements to the CA&E were scrapped as the result of the Great Depression. With the collapse of his utilities empire, Insull was forced to sell his interest in the CA&E, and the railroad was once again bankrupt by 1932. The line connecting West Chicago with Geneva and St. Charles was abandoned in 1937.

Insull's plans to make similar improvements to the CA&E were scrapped as the result of the Great Depression. With the collapse of his utilities empire, Insull was forced to sell his interest in the CA&E, and the railroad was once again bankrupt by 1932. The line connecting West Chicago with Geneva and St. Charles was abandoned in 1937.

POST WORLD WAR II DECLINE

The railroad was unable to exit from bankruptcy until 1946. Even though the railroad suffered from low revenue, high debt, and shortage of capital, wartime revenues and hopes for a stronger customer base in the growing west suburban region led the railroad to undertake an improvement of its service.

The railroad made substantial improvements to its physical plant and acquired ten new all-steel passenger cars in 1946 and made plans for eight more, with the intention of retiring the oldest wooden cars that had been on the railroad's roster from its earliest years.

The railroad made substantial improvements to its physical plant and acquired ten new all-steel passenger cars in 1946 and made plans for eight more, with the intention of retiring the oldest wooden cars that had been on the railroad's roster from its earliest years.

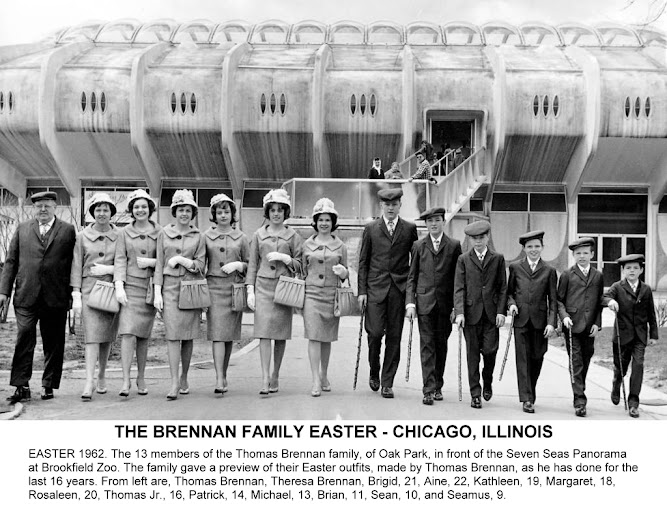

|

| 1945 CA&E MAP - CLICK TO SEE JUMBO SIZE MAP |

The expressway's construction plans provided a dedicated right-of-way for trains in the highway's median strip. However, during the estimated five years to complete the superhighway, both "L" and interurban trains would need to use a temporary street-level right-of-way. When the plans circulated in 1951, CA&E objected to the arrangement, citing the effects on running time and scheduling of its trains as they negotiated the streets of Chicago's busy West Side at rush hour. The railroad estimated that the delays would cost the railroad nearly a million dollars a year, to say nothing of the long-term effects of the new superhighway on the railroad's revenue. Another long-term concern was the railroad's downtown terminal; the new median strip line would have no access to Wells Street Terminal.

As a compromise, the railroad gained approval to cut back its service to the Desplaines Avenue station in Forest Park — the westernmost terminus of CTA Garfield Park service, after the CTA ended its unprofitable elevated train service on the CA&E's Westchester line in 1951. At the new Forest Park terminal, riders would transfer from the CA&E interurban to a CTA train to complete their commute into the city. This terminal consisted of two loop tracks (one for CA&E and one for CTA) where passengers could make a cross-platform transfer between the interurban and trains of the CTA operating over the temporary street-level trackage — and presumably the eventual new median strip Congress line. Unfortunately, with the change being put into effect on September 20, 1953, CA&E riders lost their one-seat ride to downtown Chicago. Within a few months of the cutback, half of the line's passengers abandoned it in favor of the parallel commuter service provided by the Chicago and North Western Railroad — today operated by Metra as the Union Pacific/West Line.

THE END OF THE CHICAGO AURORA & ELGIN SERVICE

The loss of one-seat commuter service to the Loop devastated the interurban. The railroad's financial condition was already shaky, and schemes to restore downtown service faced various legal or operational obstacles. As early as 1952, the railroad had sought to substitute buses for the trains, and after years of financial losses, in April 1957 the Illinois Commerce Commission authorized the railroad to discontinue passenger service. Passenger groups and affected municipalities sought injunctions that forced the railroad to temporarily continue service, but as soon as court rulings cleared the way, management abruptly ended passenger service, at noon on July 3, 1957.

Commuters who had ridden the CA&E into the city found themselves stranded when they returned to take the train home. Freight operations continued for two more years, until they too ended on June 10, 1959. No trains ran after this point, but the right-of-way and rolling stock were preserved in the event that a party stepped forward to purchase the property. The official abandonment of the Chicago, Aurora & Elgin came at 5:00pm on July 6, 1961, just over four years after the final passenger trains had run. The real estate became part of the Aurora Corporation of Illinois, a small conglomerate, which slowly sold off the right-of-way and other properties. Portions of the right-of-way are now operated as a multi-use trail called the Illinois Prairie Path.

Compiled by Neil Gale, Ph.D.

CHRONOLOGY OF THE CHICAGO AURORA & ELGIN RAILROAD

189 9

Compiled by Neil Gale, Ph.D.

CHRONOLOGY OF THE CHICAGO AURORA & ELGIN RAILROAD

February 24, 1899 – The Aurora and Chicago Railway Company

and the Elgin and Chicago Railway Company are incorporated by the Everett-Moore

syndicate

February 25, 1899 – The Chicago, Wheaton and Aurora Railroad

Company is incorporated by the competing Pomeroy-Mandelbaum syndicate

March 11, 1899 – The Aurora, Wheaton and Chicago Railway

Company is incorporated (Everett-Moore syndicate)

October 2, 1899 – The City of Aurora grants the AW&C a

franchise

1900

March 24, 1900 – President Lewis of the Cicero Board of

Trustees vetoes the ordinance granting the Aurora, Wheaton & Chicago a

franchise

March 31, 1900 – The Cicero Township grants the Aurora,

Wheaton & Chicago a fifty-year franchise

April 12, 1900 – The Village of Harlem [Forest Park] grants

the Aurora, Wheaton & Chicago a fifty-year franchise

August 23, 1900 – The City of Elgin grants the Elgin and

Chicago Railway a fifty-year franchise

February 21, 1901 – The Batavia & Eastern Railway

Company is incorporated (Everett-Moore syndicate)

March 12, 1901 – Second annual meeting of the Aurora,

Wheaton & Chicago. Stockholders change the corporate name from the Aurora,

Wheaton & Chicago Railway Company to the

Aurora, Elgin & Chicago

Railway Company (AE&C).

May 16, 1902 – The first inspection trip is held

May 17, 1902 – The Batavia Powerhouse boilers are lit for

the first time. Certain imperfections come to light and are remedied.

June 23, 1902 – The Chicago City council passes an ordinance

allowing the Metropolitan West Side Elevated to construct a terminal at Van

Buren Street and Fifth Avenue

July 29, 1902 – The first six cars are delivered from the

Niles Car & Manufacturing Company

August 25, 1902 – The Aurora, Elgin and Chicago Railway

begins regular service from

Aurora to 52nd Avenue (Laramie) in Chicago.

Passengers are required to transfer to Garfield Park trains of the Metropolitan

West Side Elevated to reach downtown Chicago.

Late September 1902 – Service begins on the Batavia branch

May 29, 1903 – The Elgin branch is placed into service

August 30, 1904 – Parlor-buffet service begins

October 3, 1904 – The Metropolitan Elevated opens the Fifth

Avenue [Wells Street] Terminal

February 9, 1905 – The Metropolitan asks for the passage of

an ordinance permitting AE&C trains to operate over the “L” to the Fifth

Avenue Terminal and the Metropolitan to operate over the tracks of the AE&C

to the Desplaines River

March 11, 1905 – The AE&C ends local service between

Forest Park and 52nd Avenue and begins operating to downtown Chicago over the

Metropolitan West Side Elevated. The Metropolitan extends Garfield Park rapid

transit service west from 52nd Avenue to Forest Park.

June 19, 1905 – The Metropolitan West Side Elevated

inaugurates funeral car service to Concordia and Waldheim cemeteries

November 23, 1905 – The Cook County and Southern Railroad is

incorporated

March 18, 1906 – The Cook County and Southern Railroad

enters service

March 26, 1906 – The Elgin, Aurora and Southern Traction

Company (the Fox River Lines) and the Aurora, Elgin and Chicago Railway (the

Great Third Rail) are formally consolidated into the Aurora, Elgin and Chicago

Railroad

June 4, 1906 – The Joint Funeral Bureau—connecting the

AE&C and the Metropolitan “L”—is created

August 27, 1908 – The Chicago, Wheaton and Western Railway

is incorporated

February 15, 1909 – The City of Geneva grants the Chicago,

Wheaton and Western a fifty-year franchise

September 21, 1909 – The Chicago, Wheaton and Western

Railway begins service with AE&C third rail equipment over what would later

be known as the Geneva branch. Trains only operate as far as West Chicago

December 1, 1909 – The Chicago, Wheaton & Western extends

service to Geneva

1910

August 25, 1910 – The Chicago, Wheaton & Western extends

service to St. Charles

October 28, 1910 – The Chicago, Wheaton & Western

Railway is deeded to the Aurora, Elgin & Chicago Railroad

March, 24, 1913 – Fire destroys the general offices in

Wheaton

September 14, 1915 – New Aurora Terminal opens in the Hotel

Arthur building

July 30, 1919 – Employees strike

August 9, 1919 – The AE&C is forced into involuntary

bankruptcy. Joseph K. Choate is named receiver.

August 21, 1919 – Strike ends

November 11, 1919 – Judge Evans grants the Northern Trust

Company permission to file a bill of foreclosure against the AE&C

1920

March 28, 1920 – The Elgin terminal is destroyed by a

tornado

March 16, 1922 – R. M. Stinson and Thomas Conway Jr. purchase

the AE&C's Third Rail Division

July 1, 1922 – The Third Rail Division of the Aurora Elgin

& Chicago Railroad is reorganized as the Chicago Aurora & Elgin

Railroad (CA&E)

May 24, 1924 – The Western Motor Coach Company is

incorporated

July 15, 1925 – Chicago Westchester & Western Railroad

is incorporated

March 4, 1926 – Samuel Insull assumes control of the

CA&E

October 1, 1926 – The CRT begins rapid transit service on

the Westchester Branch. The CA&E ends local service between Forest Park and

Bellwood

October 31, 1926 – The CA&E ends passenger service on

the Mt. Carmel (Cook County) Branch due to close proximity to the new

Westchester service

November 1, 1926 – CA&E begins motor coach service

connecting Mt. Carmel Cemetery with the Westchester “L” station

January 1, 1927 – The 420 series are cars ordered from the

Cincinnati Car Company

August 1, 1927 – CA&E trains begin stopping at Canal on

the “L” for connections to Union Station

October 29, 1929 – The stock market crashes

November 23, 1929 – Grand opening of the new Villa Park

station

1930

December 1, 1930 – The Westchester branch is extended from

Roosevelt to 22nd & Mannheim

April 1931 – The Transfer bridge connecting the Wells Street

Terminal and the Quincy “L” station opens

November 28, 1931 – Dedication of new Poplar Avenue station

February 20, 1932 – The Joint Funeral Bureau is terminated

June 7, 1932 – Samuel Insull resigns from CA&E Board of

Directors

July 21, 1932 – The CA&E enters receivership

July 13, 1934 – Last recorded funeral charter operated

March 30, 1935 – The Aurora, Elgin & Fox River Electric

operates its last electric trolleys

October 31, 1937 – Last regular trains operate over Geneva

Branch

December 31, 1939 – Final Aurora Terminal opens

1940

November 28, 1941 – 450 series cars ordered from the St.

Louis Car Company

December 7, 1941 – Bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese

April 7, 1942 – 1905 agreement allowing the Aurora &

Elgin use of the “L” to gain access to Chicago expires. No new agreement

written since both companies (CRT and CA&E) in receivership. Operations

continue without formal agreement.

November 10, 1944 – Employees strike

October 3, 1945 – First three 450 series cars arrive

December 10, 1945 – 450 series cars enter revenue service

June 28, 1946 – The Chicago Aurora & Elgin Railway

Company and the Chicago Aurora & Elgin Real Estate Liquidating Corporation

are incorporated

October 1, 1946 – Chicago Aurora & Elgin Railway Company

assumes operation of the

Chicago Aurora & Elgin Railroad. Employees strike.

October 16, 1946 – Strike ends

October 1, 1947 – The newly formed Chicago Transit Authority

(CTA) assumes control of the rapid transit system

1950

January 29, 1951 – Employees strike

March 10, 1951 – Strike ends

October 8, 1951 – CTA board votes to replace Westchester “L”

service with buses

November 15, 1951 – The Illinois Commerce Commission refuses

the CA&E’s petetion against the Van Buren street-level relocation

December 9, 1951 – CTA ends service on the Westchester

branch and instates AB skip-stop service on the Garfield route. The CA&E

resumes local service between Bellwood and Forest Park.

June 25, 1953 – Construction begins on new transfer station

at Forest Park

September 20, 1953 – The CA&E ceases operations to the

Wells Street Terminal and begins terminating trains at Desplaines in Forest

Park. Service over the Batavia branch is reduced to Monday-Friday rush hours

only. St. Charles/Geneva motor coach service is extended to Batavia at all

other times.

July 3, 1957 – The CA&E ceases all passenger service at

12:13 PM

March 6, 1958 – The Mass Transit Special is held

June 22, 1958 – Congress rapid transit line begins operating

in the median of the new superhighway

April 29, 1959 – CA&E files a petition with the Illinois

Commerce Commission to abandon freight service

June 9, 1959 – Illinois Commerce Commission authorizes the

CA&E to suspend freight service the next day

June 10, 1959 – Freight service is “suspended”

1960

July 6, 1961 – CA&E is officially abandoned at 5:00 PM

1967 – Poplar station is burned down

1970

July 5, 1976 – Villa Park and Ardmore stations are dedicated

by the Villa Park Bicentennial Commission

1979 – Undeveloped sections of CA&E right-of-way in Berkeley,

Hillside, Bellwood, and Maywood are added to the Illinois Prairie Path

1980 N/A

1990

October 1991 – Aurora Terminal platform is demolished

1996 – The Geneva Spur (following and using portions of the

Geneva branch right-of-way) is added to the Illinois Prairie Path

2000

March 2003 – Warrenvile station is demolished