In the spring of 1982, President Ronald Reagan filed his income tax return for the previous year and, in making it public, unleashed a flurry of press coverage on a fascinating but seldom-discussed topic: the many gifts, both valuable and sentimental, that our Chief Executives seem inevitably to amass while in office. President Reagan's returns showed that he had received (and was prepared to declare as income) some $31,000 (98,000 today) in gifts, including such items as silver picture frames, a crystal wine cooler, three pairs of boots, a Chinese porcelain dinner service, and a horse blanket.

|

| Abraham Lincoln Portrait as a Lawyer, 1832 |

While it lasted, the gift controversy was closely watched by the press. However, What was overlooked is that Presidential gift hoarding is not new, not even a twentieth-century phenomenon. And it would probably surprise many observers that among the Presidents who cheerfully accepted valuable presents while in office was Abraham Lincoln, who not only never disclosed them publicly (he was not required to do so) but occasionally forgot even to thank his admirers and benefactors. Had the tax and disclosure laws in the 1980s prevailed during the 1860s, the Lincolns would surely have had to contend with embarrassing revelations of their own. But such scrutiny was unheard of during Lincoln's time, as was the ethics that today seems automatically to link such presentations to ulterior motives. Coincidentally, the news of the Reagan family's gift controversies broke in the press precisely 120 years after the daughter of a Dakota judge gave Lincoln a pair of pipestone shirt studs. Lincoln, freely and without inhibition, accepted them, thanking her for her "kindness" and telling his "dear young friend" that he thought the studs "elegant."

Among the countless other items, including edibles and potables that Lincoln collected during his Presidency, were things he could not have wanted or needed, even cases of alcoholic beverages. As his friend Ward Hill Lamon remembered, Lincoln "abstained himself, not so much upon principle, as because of a total lack of appetite." once, nonetheless, a group of New York admirers "clubbed together to send him a fine assortment of wines and liquors," a White House secretary recalled. A dismayed Mary Lincoln was sure her husband would object to keeping the gift at home, so she donated the spirits to local hospitals. There, she hoped, doctors and nurses could "take the responsibility of their future."

Edible gifts─fruits and dairy products, for example─the Lincolns, seemed more than willing to keep and consume. And then there were the attractive and valuable presents: pictures, books, animals, garments, and accessories─which Lincoln almost always kept for himself. The following litany could be said, in a sense, to constitute Lincoln's own retrospective public accounting. The list serves as a reminder of how different the rules of conduct for public figures once were.

For this reason, the study is in no way intended as an indictment. No one who observed Lincoln ever thought him obsessed with personal gain or fashion. As Lamon said, "He was not avaricious, never appropriated a cent wrongfully, and did not think money for its own sake a fit object of any man's ambition." But, as Lamon added, Lincoln also "knew its value, its power, and liked to keep it when he had it." Lincoln did, in fact, defend the aspiration to wealth, declaring once that "property is desirable . . . a positive good in the world." He had even admitted, half-jokingly, back in 1836: "No one has needed favors more than I, and generally, few have been less unwilling to accept them."

sidebar

In fairness, Lincoln made this particular statement in the course of refusing a favor, noting, "In this case, favor to me would be an injustice to the public."

That also would characterize his policy where gifts were concerned─gifts that began arriving soon after his nomination to the presidency and continued arriving right up until the day of his assassination.

The gifts came from sincere admirers, blatant favor-seekers, princes and patriots, children and old women. Some made presentations in person: others sent their presents by express. On at least one occasion, a simply-wrapped little package looked so suspicious that Lincoln seriously entertained the notion that it had been designed to explode in his face.

But most of the gifts─from modest shawls and socks to expensive watches and canes─seemed to reflect a deep and widespread desire among Lincoln's admirers, chiefly strangers, to reach out to the troubled President and to be touched back in return by the acknowledgment that was certain to follow. It is difficult for the modern American living in the era of the so-called Imperial Presidency to comprehend the emotional and political simplicity inherent in these gestures. The inviting intimacy of the nineteenth-century Presidency─not to mention the code of conduct that encouraged such expressions of generosity seems to have vanished. In Lincoln's day, it thrived. And so the gifts began arriving after Lincoln won the Republican Presidential nomination in 1860.

Lincoln received dozens of presents during the campaign, ranging from the potentially compromising to the presumptuous. In the former category was a barrel of flour that arrived "as a small token of respect for your able support of the Tariff. "In the latter was a newfangled soap that inspired Lincoln to write self-deprecatingly to its inventor: Mrs. L. declares it is a superb article. She, at the same time, protests that I have never given sufficient attention to the 'soap question' to be a competent judge." Nonetheless, Lincoln admitted that "your Soap ... has been used at our house."

Whether or not the soap improved Lincoln's appearance can only be judged by looking at period pictures─and the candidate received a number of those as gifts also. "Artist expresses their happiness in supplying him with wretched wood-cut presentations," reported journalist Henry Villard. Lincoln admitted that his "judgment" was "worth nothing" when it came to art, but that did not stop art publishers from sending him examples of their work, possibly eager for endorsements that could be marketed to enhance sales. Engraver Thomas Doney, for example, sent a copy of his mezzotint portrait of the nominee, and Lincoln admitted that he thought it "a very good one." But he cautioned: "I am a very indifferent judge." Chicago lithographer Edward Mendel won a more enthusiastic endorsement (written by a secretary, signed by Lincoln) for his so-called "Great Picture" of the nominee. Acknowledging its receipt, Lincoln called it "a truthful Lithograph Portrait of myself." A month later, the full text of his letter was reprinted in a newspaper advertisement offering the print for sale. A possibly more careful Lincoln signed a more noncommittal acknowledgment when a Pennsylvania jurist shipped copies of an engraving whose costly production he had underwritten. Though it was a far better print than others received by the President and was the only one based on life sittings─Lincoln expressed thanks but no opinion. Perhaps he truly was a "very indifferent judge."

What Lincoln really thought about some of the odder gifts that arrived in Springfield in the summer of 1860 can only be imagined. The "Daughters of Abraham" sent what Lincoln described as "a box of fine peaches," accepted with "grateful acknowledgment." A "bag of books" arrived in the mail. From Pittsburgh came a "Lincoln nail"─which had been manufactured, according to its presenter, "in a moving procession of 50,000 Republican Freemen" on "a belt run from the wheel of a wagon connected with a nail machine." Each "Lincoln nail" had the Initial 'L' carved on the nailhead. "Show it to your little wife, I think it will please her curiosity," wrote the Pittsburgh man, adding: "I hope [to] God that the American people may hit the nail on the head this time in your election [as] a tribute of respect to yourself and the great cause of Truth and justice which you represent." With similar gifts arriving almost daily, Lincoln's temporary office in the Springfield State House began soon to look like "a museum, so many axes and wedges and log-chains were sent the candidate." According to the daughter of Lincoln's private secretary John G. Nicolay, the future President "used them in his explanations and anecdotes of pioneer days, making them serve the double purpose of amusing his visitors and keeping the conversation away from dangerous political reefs." Perhaps the best known of the office props─a familiar accessory visible in the background of period engravings─was the oversized wood-link chain, "sent to Mr. Lincoln by some man in Wisconsin," Nicolay wrote. "who . . . being a cripple and unable to leave his bed . . . had the rail brought in from the fence, and amused himself by whittling it out." The resulting "seat wooden chain," the New York Tribune cautioned, while made from a rail, was not made from "a Lincoln rail, as everybody is disposed to think."

|

| This woodcut was displayed in the Governor's Room of the Illinois State House (the Old State Capitol, today) in the November 24, 1860, issue of Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper. |

sidebar

The chain is on display in the Illinois State Capitol (old State Capitol) in Springfield, Illinois. It is made of wooden rail links that are about 12 inches long and 3 inches wide, which were used in the construction of the Illinois Central Railroad, the first railroad in Illinois. The chain is about 10 feet long and hangs from the ceiling of the capitol rotunda. The chain was created in the 1860s and is a symbol of the state's early history with railroads. The chain was originally used to raise and lower the chandelier in the rotunda. However, the chandelier was removed in the 1960s, and the chain has been hanging unused ever since.

Another gift received around the same time, "a pair of first-class improved wedges for splitting logs." proved similarly misleading. Everybody persists in looking upon [them] as relics of Mr. Lincoln's early life," the Tribune observed, "but which really were sent to him only about a fortnight (14 days) ago, together with a fine ax."

In June came a historic relic, a "rustic chair" that had stood on a platform of Chicago's Wigwam when Lincoln was nominated at the 1860 Republican National Convention. It was made of thirty-four different kinds of wood, "symbolizing the union of the several states, including Kansas," explained the college professor assigned to forward the memento to the candidate. "Though rude in form," the chair was meant to serve as "an Emblem of the 'Chair of State,' which . . . it is believed you are destined soon to occupy." Lincoln "gratefully accepted" both the chair and "the sentiment" but, with secession, no doubt much on his mind, wondered: "In view of what it symbolizes, might it not be called the 'Chair of State and the Union of States?' The conception of the maker is a pretty, patriotic, and national one."

Many gifts were similarly inspiring─or at the least, friendly. If ever there was a danger to Lincoln in accepting every package that came through the mail, it could never have been more apparent than on October 17, when he received this warning from a Kansas man: "As I have every reason to expect that you will be our next President─I want to warn you of one thing that you be exceedingly careful what you eat or drink as you may be poisoned by your enemies as was President Harrison and President Taylor." That same day, a Quincy, Illinois, man sent Lincoln "a Mississippi River Salmon," with the hope that "the fish . . . caught this morning will grace the table of the next President of the United States." There is no record that Lincoln responded to either letter, but it is amusing to wonder how he reacted to the receipt of the food concurrently with the receipt of the warning.

After Lincoln's election three weeks later, the steady stream of gifts grew into a flood. "A pile of letters greeted him daily," wrote Villard, and many packages bore gifts. Books, for example, arrived frequently. "Authors and speculative booksellers freely send their congratulations," Villard explained, "accompanied by complimentary volumes." Many of the other gifts were homespun─others merely "odd."

In December, one New York "stranger" sent two specially made hats. "A veritable Eagle Quill" arriving from Pennsylvania, plucked from a bird shot in 1844 in the hope that the pen fashioned from it would be used by Henry Clay to write his inaugural address. For sixteen years, its owner had waited for a candidate of equal stature to win the Presidency. And thus he wrote to Lincoln:

I . . . have the honor of resenting it to you in your character of President-elect to be used for the purpose it was originally designed.

What a pleasing and majestic thought! The inaugural address . . . written with a pen made from the quill taken from the proud and soring emblem of our liberties.

If it is devoted in whole or in part to the purpose indicated, would not the fact and the incident be sufficiently potent to "Save the Union."

The new year of 1861 brought more valuable gifts, including several canes. One redwood, gold and quartz-handled example were judged "highly artistic and in very good taste" by visiting sculptor Thomas Dow Jones. Mrs. Lincoln received a sewing machine; some Cleveland millworkers sent Lincoln a model T-rail: and Chicago City Clerk Abraham Kohn sent a watercolor he had painted, complete with Hebrew inscriptions.

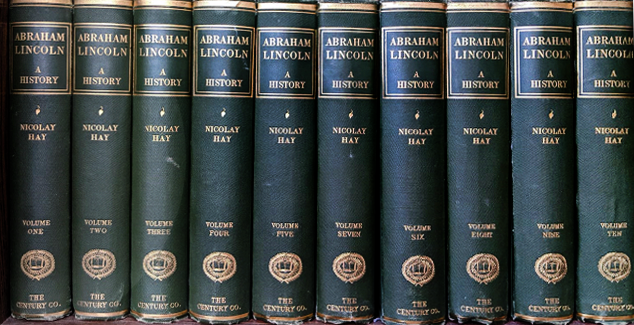

|

| Thomas Dow Jones |

Yet another Allusion to Lincoln's "beau ideal (perfect beauty: French)," Henry Clay, was offered with the arrival in February of a decades-old medal from a limited strike run of 150. One had been "reserved, at the time," explained the presenter, "with the intention . . . of presenting it to the citizen of the school of Henry Clay, who should first be elected to the Presidency. I rejoice that that event has, at last, occurred." Lincoln replied with "heartfelt thanks for your goodness in sending me this valuable present," expressing the "extreme gratification I feel in possessing so beautiful a memento of him whom, during my whole political life, I have loved and revered as a teacher and leader."

More clothing arrived as well. A Boston wholesaler sent what Lincoln acknowledged as "a very substantial and handsome overcoat," an "elegant and valuable New Year's Gift." A Westerner sent "a Union grey shawl, made of California wool . . . together with a pair of family blankets" as samples of "Pacific State weaving." Thanking the donor for the "favor," Lincoln noted the forward state of California manufacturers, which those articles exhibit." Shortly before leaving for Washington, as he stared into a mirror admiring a new topper sent by a Brooklyn hatter, Lincoln reportedly remarked to Mary Lincoln: "Well, wife, there is one thing likely to come out of this scrape, anyhow. We are going to have some new clothes!" As he had predicted, three days before his fifty-second birthday, Titsworth & Brothers, Chicago clothiers, donated an expensive suit for Lincoln to wear at his inauguration.

sidebar

The word "hatter" can refer to both men and women who make or sell hats, but it is more commonly used to refer to men. In the 18th and 19th centuries, mercury was used in the production of felt, which was commonly used in the hat-making trade at the time. Long-term exposure to mercury vapors could cause a condition known as erethism, which is characterized by tremors, slurred speech, and other neurological symptoms. This led to the widespread belief that hatters were often mad, which is why the phrase "mad as a hatter" came into use.

That same day he received a more peculiar gift, one that arrived in a package so "suspicious" looking that Thomas D. Jones, for whom Lincoln was then sitting for a sculpture, worried at first that it might contain "an infernal machine to torpedo." Jones placed it "at the back of a clay model" of Lincoln's head, "using it as an earthwork, so, in case it exploded, it would not harm either of us." It turned out to be a whistle fashioned from a pig's tail, which Tad Lincoln was soon suing "to make the house vocal if not musical . . . blowing blasts that would have astonished Roderick Dhu." Both the suit and whistle inspired Villard to file this report on February 9:

A large number of presents have been received by Mr. Lincoln within the last few days. The more noteworthy among them are a complete suit . . . to be worn by his excellency on the 4th of March. . . . The inauguration clothes, after being on exhibition for two days, will be tried on this evening─a most momentous event to be sure. . . . The oddest of all gifts to the President-elect came to hand, however, in the course of yesterday morning. It was no more or less than a whistle made out of a pig's tail. There is n "sell" in this. Your correspondent has seen the tangible refutation of the time-honored saying, "No whistle can be made out of a pig's tail," with his own eyes. The doner of the novel instrument is a prominent Ohio politician. . . . Mr. Lincoln hugely enjoyed the joke. After practicing upon this masterpiece of human ingenuity for nearly an hour, this morning, he jocosely remarked that he had never suspected, up to this time, that "there was a music in such a thing as that."

Even as Lincoln prepared to leave for Washington the following day, he was asked to accept one more gift specially designed for the inaugural journey. A Burlington, Iowa, man proposed making a [chain] mail shirt for Lincoln to wear for protection.

sidebar

Mail shirts protected against slashing and piercing weapons but were not as effective against blunt force trauma. The rings are typically about 1 inch in diameter and linked together in a pattern that forms a tight, flexible mesh. The weight of a mail shirt can vary depending on the size and thickness of the metal rings, but they typically weigh between 10 and 30 pounds.

He even offered to plate it "with gold so that perspiration shall not affect it. The instructions continued: "It could be covered with silk and worn over an ordinary undershirt. . . . I am told that Napoleon III is constantly protected in this way" Lincoln declined the offer and left Springfield armorless. But he was not long without other sorts of gifts. En route to Washington D.C., he was given baskets of fruit and flowers. And in New York, he was given silk top hats from both Knox and Leary, rival hatters. Asked to compare them, Lincoln diplomatically told the New York World that they "mutually surpassed each other."

At last, on March 4, Lincoln moved into the White House. But the flood of gifts only increased. A carriage came from some New York friends, and a pair of carriage horses were reportedly sent to Mrs. Lincoln. Presumably, they were hitched together. A more modest donor, disclaiming personal ambition but hearing that Lincoln was "constantly besieged with applications for office," thought "that something nice and palatable in the way of good Butter might do you good and help to preserve your strength to perform your arduous duties." Along with the tun of butter came advice: "Keep a good strong pickle in this butter and in a cool place, then it will keep sweet till July." There is no record of whether the butter stayed fresh through the summer.

During the same hot months, Secretary of State William H. Seward gave the Lincolns a quite different gift: Kittens. The pets were intended for the Lincoln children, but the President reportedly liked to have them "climb all over him" and grew "quite fond of them" himself.

|

| 1861 Picture of "Tabby." |

Abraham Lincoln received Tabby and Dixie, his two cats, in 1861. It was the same year that Lincoln became President of the United States.

|

| Case in point |

John Hancock's niece sent Lincoln "an interesting relic of the past, an autograph of my uncle, having the endorsement of your ancestor, Abraham Lincoln, written a century ago: humbly trusting it may prove a happy augury of our country's future history." Lincoln returned his "cordial thanks" for both relics and "the flattering sentiment with which it was accompanied." There were spirit gifts to warm the President's heart. A "poor humble Mechanic" from Oho forwarded "one pair of slippers worked by my Little Daughter as a present for you from her." A Cincinnati man recommended the "quick and wholesome nourishment" of "Pure wine" made from grapes he planted himself. He sent a case.

Some gifts were meant to preserve honor. When a Brooklyn man read that no American flag flew over the White House, he asked for "the privilege, the honor, the glory" of presenting one. The "ladies of Washington" made a similar offer a few days later. No reply to either has been found. Nor did the President respond to an offer of toll-free carriage rides on the Seventh Street Turnpike or the gift of Dr. E. Cooper's Universal Magnetic Balm," good for Paralysis, Cramps, Colics, Burns, Bruises, Wounds, Feves, Cholera Morbus, Camp Disease, etc., etc., etc.," despite advice that Lincoln "trust it to you own family and friends (especially to General Scott). But he did respond to the gift of "a pair of socks so fine, and soft, and warm" that they "could hardly have been manufactured in any other way than the old Kentucky Fashion."

Foreign dignitaries usually sent far more exotic presents, some so valuable that Lincoln decided he could not accept them. When the King of Siam (Thailand today), for example, presented "a sward of costly materials and exquisite workmanship" along with two huge elephant tusks, Lincoln replied: "Our laws forbid the President from receiving these rich presents as personal treasures. They are therefore accepted . . . as tokens of your goodwill and friendship for the American people." Lincoln asked Congress to decide upon a suitable repository, and it chose the "Collection of Curiosities" at the Interior Department. Yet another gift offer from the King of Siam─a herd of elephants to breed in America─was refused outright, with Lincoln explaining dryly: "Our political jurisdiction . . . does not reach a latitude so low as to favor the multiplication of the elephant.

Gifts from domestic sources were not only less cumbersome, they were proper to accept. White rabbits arrived for Tad, and Clay's son presented Clay's snuffbox in the ultimate expression of faith that Lincoln had attained the stature of his political hero, Henry Clay. Earlier, when a Massachusetts delegation presented Lincoln with an "elegant whip," the ivory handle of which bore a cameo medallion of the President, he replied, according to author Nathaniel Hawthorne, who witnessed the scene, with "an address . . . shorter than the whip, but equally well made."

I might . . . follow your idea that it is . . . evidently expected that a good deal of whipping is to be done. But, as we meet here socially, let us not think only of whipping rebels, or of those who seem to think only of whipping Negroes, but of those pleasant days which it is to be hoped are in store for us when seated behind a good pair of horses, we can crack our whips and drive through a peaceful, happy and prosperous land.

"There were, of course, a great many curious books sent to him," artist Frances Bicknell Carpenter recalled, "and it seemed to be one of the special delights of his life to open these books at such an hour, that his boy [Tad] could stand beside him, and they could talk as he turned the pages." Actor James H.Hackett sent his Notes and Comments upon Certain Plays and Actors of Shakespeare. Lincoln had seen Hackett perform Falstaff in Henry IV at Ford's Theatre, but when he acknowledged the gift, he admitted, "I have seen very little of the drama." Hackett published the letter for his "personal Friends" only, but the press got hold of it and quoted it to illustrate Lincoln's ignorance. Hackett later apologized. Canes were also sent in abundance, typically hewn from some hallowed wood. Lincoln received one cane made from the hull of a destroyed Confederate ship, Merrimac, and another from a sunken Revolutionary War Ship, Alliance. Yet another, with a head carved in the shape of an eagle, was made from wood gathered in the vicinity of the 1863 Battle of Lookout Mountain.

sidebar

Lookout Mountain is famous for the Battle of Lookout Mountain, which was fought on November 24, 1863, as part of the Chattanooga Campaign of the Civil War. The battle was fought on the slopes of Lookout Mountain, which is located in Tennessee, just across the state line from Georgia. The Union forces, led by Major General Joseph Hooker, defeated the Confederate forces, led by Major General Carter L. Stevenson. The victory gave the Union control of Lookout Mountain and helped to break the Confederate siege of Chattanooga. The battle was also known as the Battle Above the Clouds because it was fought in thick fog. The fog obscured the battlefield and made it difficult for the soldiers to see each other. This led to some confusion and casualties, but it also helped to protect the Union forces from Confederate artillery fire. The Battle of Lookout Mountain was a significant victory for the Union. It helped to break the Confederate siege of Chattanooga and opened the way for the Union to take control of the city. The victory also boosted Union morale and helped to turn the tide of the war in the Western Theater.

Journeying to Philadelphia in June 1864 to attend the Great Central Sanitary Fair (held from June 7 to June 28, 1864), Lincoln was given a staff made from the wood of the arch under which George Washington had passed at Trenton, New Jersey, en route to his inauguration.

sidebar

The Great Central Sanitary Fair was a fundraiser for the United States Sanitary Commission, a volunteer organization founded at the beginning of the Civil War to provide medical care for Union soldiers.

Were all these gifts made with no ulterior motive in Mind? It is impossible to say─although Lincoln might have sniffed out one potentially compromising situation in 1863 when Christopher M. Spencer gave him a new Spencer Rifle, along with a demonstration of the proper way to assemble it. A large War Department order could make a munitions man wealthy overnight, and there was no shortage of new military gadgetry sent to the White House. Clerk William Stoddard reported that his own office eventually "looked like a gunshop." Similarly, when an Indian agent fighting a theft charge petitioned Lincoln to intervene for him, enclosing quilled moccasins as a gift, Lincoln took off his boots and tried them on whit a smile. But he did not intervene in the case. later, when California railroad men presented Lincoln with an exquisite, thirteen-inch-long spun gold watch chain, it was quite possible the delegation was thinking not so much about how elegant the adornment would look on the Presidential waistcoat but how lucrative would be government support for the building of roadbeds out west. Lincoln apparently did not care much. He posed for his most famous photographs wearing the ornament. An ideal companion piece, a gold watch, arrived in late 1863, forwarded by a Chicago jeweler on behalf of the Sanitary Commission. Lincoln expressed thanks for the "humanity and generosity" of which he had "unexpectedly become the beneficiary." It seemed the jeweler had promised the watch to the largest contributor to the Ladies Northwestern Fair.

sidebar

The Ladies Northwestern Fair was a fund-raising event held in Chicago, Illinois, from May 30 to June 21, 1865. It was organized by women to benefit the United States Sanitary Commission, which provided medical care to Union soldiers during the Civil War. The fair was a huge success, raising over $1.1 million ($20.6 million today).

Lincoln had donated a copy of the Emancipation Proclamation. It sold for $3,999, winning him the prize. Lincoln seemed pleased also by a rather hideous elkhorn chair presented by a frontiersman, Seth Kinman. They admired an Afghan made by two New York girls ("I am glad you remember me for the country's sake) and the Vermont cheese forwarded by an admirer from Anby ("superior and delicious"). He liked the book of funny lectured he received from a comic "mountebank," and the "very excellent . . . very comfortable" socks knitted by an eighty-seven-year-old Massachusetts woman. Lincoln thought these "evidence, of the patriotic devotion which, at your advanced age, you bear to our great and just cause."

A "very comfortable" chair came from the Shakers; a fine "suit of garments" was made to Lincoln's order and displayed for a while at a Sanitary Fair; a "useful" Scotch plaid; a "handsome and ingenious pocket knife" (acknowledged not once but twice); a red, white, and blue silk bedspread emblazoned with stars and stripes and the American eagle; an exquisite gold box decorated with his own likeness and filled with quartz crystal─all of these were received and acknowledged in 1864.

More art came to hand as well. Sculptor John Rogers sent his statuary group, Wounded Scout─A Friend in the Swamp, which Lincoln thought "very pretty and suggestive." The President found "pretty and acceptable" a gift of photographic views of Central Park in New York City, which its senders, E, & H. T. Anthony & Co., hoped would "afford you a relaxation from the turmoil and cares of office." Photographer Alexander Gardner sent along the results of an 1863 sitting, which Lincoln thought "generally very successful," adding: "The imperial photograph, in which the head leans upon the hand, I regard as the best that I have yet seen." Lincoln seemed less taken with a photographic copy of an allegorical sketch by Charles E. H. Richardson called The Antietam Gem.

sidebar

The Battle of Antietam was fought on September 17, 1862, in Sharpsburg, Maryland. The battle was one of the bloodiest in American history and resulted in over 23,000 casualties.

As a contemporary described the scene: "Twilight is seen scattering the murky clouds which enveloped and struck terror to the people in the days of Fort Sumter." The Union was shown "Crushing out Secession, unloosening its folds from around the Fasces of the Republic." The cart-de-visite copy had been sent in the hope that Lincoln would want the original after the conclusion of its display at a Philadelphia fair. Instead, Lincoln suggested tactfully that it be "sold for the benefit of the Fair." Despite his apparent aversion to such representational works, the President did sit still once for the presentation of an allegorical tribute to Emancipation "in a massive carved frame." Lincoln "kindly accorded the desired opportunity to make the presentation, which occupied but a few minutes." remembered artist Francis Carpenter, who witnessed the scene. After it was over, Lincoln confided to Carpenter precisely how he felt about the gift. "It is what I call ingenious nonsense," he declared.

According to Carpenter, of all the gifts Lincoln ever received, non gave him "more sincere pleasure" than the presentation by the "Negro people of Baltimore" of an especially handsome pulpit-size Bible, bound in violet velvet with solid gold corner bands. "Upon the left-hand corner," Carpenter observed, "was a design representing the President in a cotton field knocking the shackles off the wrists of a slave, who held one hand aloft as if invoking blessings upon the head of his benefactor." The Bible was inscribed to Lincoln as "a token of respect and gratitude" to the "friend of Universal Freedom." Rev. S. W. Chase, in making the presentation, declared: "In future, when our sons shall ask what these tokens mean, they will be told of your mighty acts and rise up and call you blessed." Lincoln replied: "I return you my sincere thanks for this very elegant copy of the great book of God . . . the best gift which God has ever given man."

Another touching ceremony took place the next year when a Philadelphia delegation gave Lincoln "a truly beautiful and superb vase of skeleton leaves, gathered from the battle-fields of Gettysburg."

sidebar

Lincoln told the group that "so much has been said about Gettysburg, and so well said, that for me to attempt to say more may, perhaps, only serve to weaken the force of that which has served to weaken the force of that which has already been said." Interestingly, he was referring not to his own words spoken on November 19, 1863, but to those of principal orator Edward Everett, who had died just nine days before the vase presentation.

Lincoln was deeply moved as well when Caroline Johnson, a former slave who had become a nurse in a Philadelphia hospital, arrived at the White House to express her "reverence and affection" for Lincoln by presenting him with a beautifully made collection of wax fruits and an ornamented stem table-stand. Together with her minister, she arrived in Lincoln's office, unpacked the materials, and set up the stand and fruits in the center of the room as the President and First lady looked on. Then she was invited to say a few words, and as she later recalled:

I looked down to the floor and felt that I had not a word to say, but after a moment to two, the fire began to burn, . . . and it burned and burned till it went all over me. I think it was the Spirit, and I looked up to him and said: "Mr. President, I believe God has hewn you out of a rock for this great and mighty purpose. Many have been led away by bribes of gold or silver, of presents, but you have stood firm because God was with you." With his eyes full of tears, he walked round and examined the present, pronounced it beautiful, thanked me kindly, but said: "You must not give me the praise─It belongs to God."

By the last few months of his life, the novelty of Presidential gifts seemed finally to wear off for Lincoln. When in late 1864, the organizers of a charity fair asked him to contribute the mammoth ox. "General Grant," recently sent by a Boston donor, Lincoln seemed totally unaware that he had been given the beast. "If it is really [mine] . . . I present it," he wrote incredulously. It was auctioned off for $3,200 ($77,500 today). A new pattern had been established. Gifts were still arriving, but Lincoln was no longer taking notice. There is no record of any acknowledgments, for example, for the many Thanksgiving gifts received in November 1864.

Then, only two months before the assassination, Lincoln had to be reminded by Abolitionist leader William Lloyd Garrison that he had also failed to acknowledge the gift a full year before of a "spirited" painting depicting Negores awaiting the percise moment of their emancipation. "As the money was raised," Garrison wrote testily, "by ladies who desire that the donors may be officially appraised of its legitimate application, I write on their behalf." Noting that visitors had "seen the picture again and again at the White House," Garrison pressed Lincoln to avoid further "embarrassment" by taking note that "the painting . . . was duly received." A weary Lincoln apologized for his "seeming neglect," explaining weakly that he had intended "to make my personal acknowledgment . . . and waited for some leisure hour, I have committed the discourtesy of not replying at all. I hope you will believe that my thanks though late, are most cordial." The letter was written by Secretary John Hay; Lincoln merely signed it.

The very last recorded gift presented to Lincoln came from a delegation of fifteen visitors only hours before the President left for his fateful visit to Ford's Theatre. Anticlimactically, the presentation ceremony─such as it was─took place in a hallway. A spokesman made a brief impromptu speech, and Lincoln was handed a picture of himself in a silver frame. There is no record of his reply. But by then, Lincoln had been given a far more precious gift: the surrender of Lee's army at Appomattox. Before, he had very much time to savor it; however, he was dead.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.