Numbering streets and buildings allows those unfamiliar with a building or home to locate it more easily. Early on, Chicago created a few numbered streets on the North and West Sides, but these did not last. By the 1860s, the city had numbered east-west streets on the South Side. Chicago's earliest building numbers were employed in the 1840s on Lake Street, the city's business center. Homes and businesses elsewhere were described in terms of street intersections, such as "on Kinzie Street, east of Dearborn." The use of house numbers spread slowly. During the Civil War, however, the U.S. Post Office began free door-to-door mail delivery, contingent upon the numbering of houses, and house numbering became common.

However, each "division" or side of the city had its own system, and many streets were numbered from the meandering rivers or shoreline so that house numbers on parallel streets often failed to line up neatly. Beginning about 1881 on the South Side, house numbers on north-south streets were tied to the numbered east-west streets. Thus, for example, 2200 State was at 22nd Street. Here, numbering was much more regular than elsewhere.

Ordinary Chicagoans have adapted to this house-numbering regime's fuzzy but familiar geometry. Still, delivery workers and strangers sometimes found it confusing, and the confusion added to business costs. A campaign led by Edward P. Brennan resulted in a new house-numbering system in 1908 and street-naming reforms. All buildings were numbered beginning at Madison and State Streets, making Chicago's business and retail heart the center of the new system. The clean geometry of straight lines and right angles guaranteed uniformity in numbering. Throughout Chicago, the "twenty-four hundred block" is just west of Western Avenue, while the 3200 block is just west of Kedzie. House numbers rise by 800 every mile, or 100 per long block, except on the South Side, where numbered streets retained their uneven spacing from Madison to 31st Street (where the first three "mile" intervals are at 12th, 22nd, and 31st Streets).

Suburban areas gradually adopted house numbering as well, sometimes establishing their own systems and sometimes extending the city of Chicago's name and numbering. Lake View used the Chicago system on north-south streets but created its own scheme for east-west streets, with Western Avenue as its baseline. This scheme was continued when Lake View was annexed by the city in the late nineteenth century. Other areas annexed by the city were obliged to adopt the city's system. In the 1890s, Oak Park, foreshadowing later changes in Chicago, adopted a numbering system based on 800 to the mile—with one hundred to each long city block—and used Chicago's State Street as its baseline.

Chicago's numbered street system has been extended far south into suburban communities, and some suburbs have adopted the city's house-numbering system. However, others, emphasizing their communities' uniqueness, adopted their own systems.

|

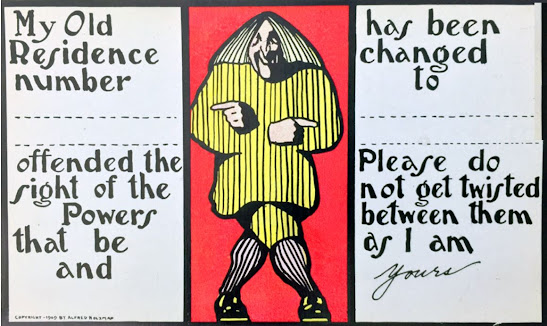

| Change of Address Postcard, 1909. |

The house and street numbering system was inconsistent and became more so as Chicago annexed adjacent towns. In 1880 the City Council took steps toward addressing the problem with an ordinance that adjusted house numbers south of Twelfth Street (Roosevelt Road) to match the numbered streets on the south side. Still, the measure neglected the central and northern portions of the city. Large-scale annexations of 1889 complicated matters further throughout the city. In 1901 Edward P. Brennan proposed a solution, recommending State and Madison as the baseline for a city-wide street numbering system. In 1908 after years of debate, alterations, and improvements, the Chicago City Council adopted the plan, with implementation enforced beginning September 1, 1909. John P. Riley of the city's maps department was instrumental in hammering out the plan's final form.

The initial legislation exempted the Loop, but after its initial success, the Council amended the ordinance in 1910 to include that area, with a compliance date of April 1, 1911. In the following years, Brennan campaigned tirelessly to eliminate duplicate street names and ensure that the names of broken-link streets would remain the same throughout the city. Hundreds of street name changes resulted, Brennan, suggesting many of the names adopted. The current method for adopting honorary street names reflects the determination of city leaders to preserve this rational system. On December 3, 1984, the City Council passed an Honorary Street Name Ordinance crafted by Charles O'Connor, head of the city's Bureau of Maps and Plats. Instead of changing a street's name to recognize a local hero, the city would create an honorary designation posted on a particular brown sign.

The "real" address, however, for the purposes of mail delivery, police and fire departments, and the friend visiting from out of town, remained as part of the city's official grid-imposed street naming and numbering system.

Edward Brennan claimed never to have personally profited from his work on the reform of Chicago's addresses. His efforts were recognized in a resolution of the City Council on April 21, 1937. When Edward Brennan died in 1942, not only had the city been renumbered, but also at his urging, the City Council had changed hundreds of street names. Brennan failed to win implementation for every aspect of his vision. For example, designations of Street, Avenue, and Road continued to be used randomly instead of being assigned to east-west, north-south, and diagonal streets, respectively ─ but his overall plan still makes life easier for every Chicago resident and visitor.

The renumbering of Chicago's streets in 1909 and 1911 obviously required a great deal of preparation. Residents needing to notify correspondents of a new house number could find a variety of preprinted postcards in styles ranging from humorous to decorative to matter-of-fact. The August 21, 1909, Record-Herald headlined an article, "Postcard makers Reap Harvest on Change in City's House System."

Besides postcard makers, mapmakers also saw a dramatic rise in business due to the new system. This 1910 Rand McNally map shows that every eight blocks on the grid (starting from State Street and moving west) marks a major thoroughfare.

Brennan acted as chair of the Subcommittee on Street Numbers and Signs at the City Club, which actively campaigned to eliminate duplicate street names and post clear signage. Among the items saved in Brennan's scrapbooks are several letters from companies ranging from Western Union and Marshall Field's department store to Riddiford Brothers Janitors' Supplies, supporting the plan to eliminate duplicate street names. After the second major renaming initiative in 1936, the proceedings of the Chicago City Council for April 21, 1937, proudly noted, "There are now only 1363 street names in Chicago for 3624 miles of streets. There are now fewer street names in Chicago than in any other city in the country of even one-half the area of Chicago."

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Chicago used to make it easy to drive in and know where you were. On the light poles they had 2 numbers 1 above the other. One number told you the 100 block you were on the 2d number told you the pole number. Say you were driving east on Addison and looking for say 4220 West Addison, you looked for the 100's number to know where you were. As you headed east the number would show say 52 in 1 block and then 51 the next block. It made it easy to know when you were getting close to your destination as you didn't have to look ad the address as the light poles told you where you were.

ReplyDeleteThe Chicago numbering system on light poles was a two-part system that used a combination of numbers to identify the location of a light pole. The first number, located next to the second number, indicated the 100 block that the light pole was located on. The second number, located next to the first number, indicated the pole number within that 100 block.

DeleteFor example, a light pole with the number "1002" would be located on the 100 block of North State Street, and it would be the second light pole on that block.

This numbering system was used in many areas of Chicago, including the Loop, the Near North Side, and the South Loop. It was discontinued in the early 2000s, and the current system uses a single number to identify each light pole.

The Chicago light poles numbering system was a simple and effective way to identify light poles. It was easy to remember, and it allowed emergency responders to quickly locate light poles in the event of a road emergency.

Great historical facts, Neil.

ReplyDelete