Few towns in Illinois played a more critical role in Abraham Lincoln's legal and political development than Bloomington, McLean County's seat, about 65 miles northeast of Lincoln's hometown of Springfield. Bloomington was the location for some of Lincoln's most important confrontations with political archrival Stephen A. Douglas.

|

| 1860 Portrait of Abraham Lincoln by Leopold Grozelier. |

Lincoln was even briefly a landowner in Bloomington, buying two lots in 1851 and selling them in 1856. Bloomington was home to some of Lincoln's most important legal and political colleagues like Judge David Davis, attorney Leonard Swett and businessman Jesse W. Fell. Contemporary journalist Walter Stevens observed: "No man in politics ever had more loyal, more intelligent attention to his interests than these three Bloomington men [Fell, Davis, Swett] gave to the candidacy of Mr. Lincoln. Their attachment to him was something phenomenal in politics." Their efforts were critical to Mr. Lincoln winning the Republican presidential nomination in 1860.

When Lincoln first visited Bloomington in 1837, reported Lincoln scholar Harry E. Pratt, "the town boasted eight stores, three general and dry good stores, two groceries (taverns) or doggeries (cheap saloon), two lawyers, and three physicians. The town had a handsome Academy building, two steam mills for sawing, Presbyterian and Methodist meeting houses, and a total population of 700."

sidebar

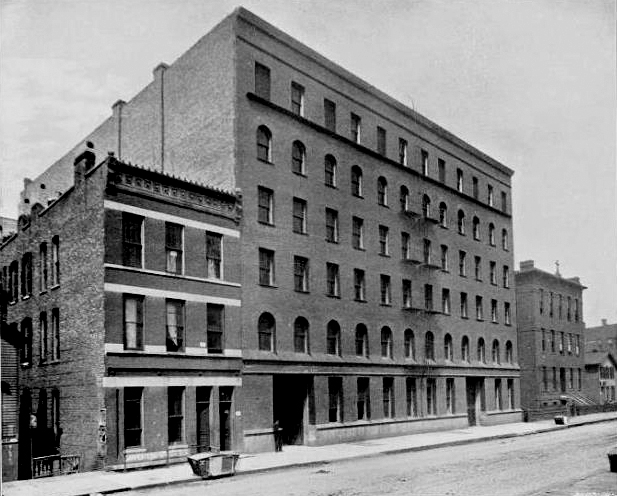

The Springfield Academy (Academy building), opened to 36 pupils both boys and girls, on the west side of Fifth Street, between Monroe Street and Capitol Avenue (formerly Market) in 1840.

In 1837, about a year later, Lincoln had his first public debate there with Stephen A. Douglas. Lincoln filled in for his ailing law partner, John Todd Stuart, who was campaigning against Douglas for the State's northern congressional seat.

The residents of Bloomington became some of Lincoln's most critical political backers in his quest for state and national office. Lincoln biographer Michael Burlingame wrote that the Maryland-born David Davis "quickly acquired a reputation as an outstanding business lawyer. A faithful Whig, he was only modestly successful in politics. . . . Ambitious, vain, fun-loving, industrious, and genial, he eagerly acquired friends and money." Historian Don E. Fehrenbacher wrote: "The two became good friends. When Davis became a circuit judge, he reportedly showed such a 'marked difference . . . to Mr. Lincoln that Lincoln threw the rest of us into the shade,' according to one lawyer." In 1844 Davis described the court in Bloomington:

"Generally, those with no business come to court the first day. It begins at eleven o'clock in the morning. A Grand jury is sworn in and charged by the prosecuting attorney, never by the Judge. The court adjourns to the next morning. This lets the presidential electors talk the rest of the day. Lincoln is a Whig elector. Lincoln is the best stump speaker in the State. Shows the want of early education, but has great powers as a speaker." Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg wrote: "A graduate of Kenyon College, Davis had come west and grown up with Bloomington. He had a keen eye for land deals and owned thousand-acre tracts. On his large farm near Bloomington, he had a frame mansion where Lincoln stayed occasionally. In many ways, the destinies of Davis and Lincoln were to interweave."

The McLean county seat was an essential stop on the Eighth Judicial Circuit frequented by America's future President. Lincoln, for example, played a crucial role in the slander trial of Bloomington millionaire Asahel Gridley, a Davis law partner turned businessman whose outspoken comments and behavior had a habit of annoying people. When Lincoln first saw Gridley's ostentatious new house, he asked his friend: "Do you want everybody to hate you, Gridley?" Historian Harry E. Pratt wrote: "General Gridley, lawyer, banker and land dealer, once becoming angry at William F. Flagg, reaper manufacturer, poured slanderous accusations upon him, with the result that Flagg sued him. As Gridley cooled off, he regretted his impulsiveness, but the case was at law, and the only thing to do was to defend it. Lincoln was retained and soon saw that he had a bad case. 'Gridley,' he said, 'do you know what my defense is going to be in the case' 'No,' asked Gridley, 'what is it?" 'My line of defense is going to be that your tongue is no slanderer, that the people generally know you to be impulsive and say things you do not mean, and they do not consider what you say as slander." Lincoln then settled the case out of court.

Many stories about Lincoln's legal expertise and character originate in Bloomington. Pratt wrote: "Zachariah Lawrence, better known as 'Squire,' was a justice of the peace in Bloomington from 1846 to 1881. The Squire remembered Lincoln coming to his office and sitting at a table, taking a half sheet of note paper and announcing that he had to write a declaration. When the Squire remarked that it was a pretty small piece of paper to write a court declaration on, Lincoln 'that he had always found it best to make few statements, for if he made too many, the opposite side might make him prove them.'" Almost without exception, Lincoln was present at every spring and summer court session in Bloomington for two decades. Pratt wrote: "The social side of Lincoln's visits to Bloomington is of interest. Four families took turns giving dinners to the lawyers during court week — David Davis at his place, 'Clover Lawn,' Wm H. Allin, 307 W. Jefferson, James Miller, 801 S. Madison, and Jesse W. Fell at 'Fell Park' in North Bloomington, now in Normal, Illinois."

Some of the important stories of Lincoln in Bloomington are from teenagers and young men who observed Lincoln in Bloomington's law offices, courts, and streets. "Mr. Lincoln was fond of children. He took notice of boys, remembered them and spoke to them by name," recalled James S. Ewing of his Bloomington boyhood. "My father was Democrat. He nicknamed one of my brothers' Democrat,' and he went by that name for years. Mr. Lincoln was a Whig. One day, he commented on the nickname 'Democrat.' He said to my other brother, the one next to me, 'I'll call you Whig.' That was Judge W. G. Ewing of Chicago. He always has kept the name Mr. Lincoln bestowed upon him. He has always been called by his friends 'Whig Ewing' instead of William Ewing. I only mention this to show Mr. Lincoln's attention to boys, even to the extent of knowing their names. Although Mr. Lincoln and my father differed in politics, they were great friends." Ewing later recalled: "Lincoln was a great cross-examiner in that he never asked an unnecessary question. He knew when to stop with a witness and when a man has learned that he is entitled to take rank as an expert questioner."

Years later, Robert H. Browne recalled coming to work at the Bloomington law office of Judge David Davis and Asahel Gridley as a teenager, "This was of incalculable benefit to any student, affording, at the same time, the great opportunity of a near acquaintance and close friendship with Mr. Lincoln through the years of his wonderful rise and development." Browne wrote:

"Mr. Gridley's introduction of the somewhat backward boy — the writer — to Mr. Lincoln was characteristic, and in those days, it was a noted circumstance in any boy's life to be made a near acquaintance and be as favorably introduced to prominent lawyers, who were persons of much distinction to country boys. Our family had known Mr. Lincoln only a few years before, tolerably well, . . . but nothing like so intimately as we did Judge [Stephen A.] Douglas. Hence, to meet Mr. Lincoln in such favorable circumstances as Mr. Gridley had arranged for was a notable, almost exciting, event."

"When the time arrived, Mr. Lincoln walked into the office — a tall, mild-manner, friendly-looking man, with the most comfortable and easy manner about him in his address and presence you could well imagine. Mr. Gridley met him, shook hands with him cordially, and after some personal remarks, said, in his rapid, clear voice, his words rattling like hailstones on a tin roof: "Mr. Lincoln, I am very glad to have you here with us again. I have made some changes. This will be your desk, and you can arrange the tables as you like. This young man, Robert, will render you any assistance he can. He is here attending school. His people live in the country. He has been thinking about things for himself and stirring them up very lively in some quarters, and, as I have advised him, he has been more cautious recently. Still, despite it, he insists that he is an out-and-out Abolitionist, without evasion or any sort of qualification. I told him he was very foolish and that being a little older would bring him a lot of trouble. Anyway, with all my care and prudence, he is far ahead of public sentiment."

"Mr. Lincoln took my hand with a warmth and expression that lightened up the soul of anyone he respected or held to be a friend, saying: 'Yes, Mr. Gridley, I will get along first rate. This will suit me very well,' and, turning to me: 'The young man will do as well as the rest of us, but he must not be kept out of school an hour on my account. It seems to me, Robert, that I ought to know you, but you never know about boys of your age, who change every year and grow out of your knowledge.' I replied: Mr. Lincoln, I know who you are very well. My father knew you when we lived in Springfield when he helped to finish the south front and the top work of the Capitol building. 'Yes, yes, I knew Mr. Browne, the Scotchman. I remember him quite well. Of course, you are an Abolitionist.' When this was done, the friendly relation of a lifetime had begun."

"The acquaintance thus begun with him was developed, strengthened, and continued," Browne noted. "It became a perpetual pleasure. It was an open, cheerful, good-willed friendship that was never cramped or stained. I was intimate with him in this office intercourse for something over three years and had a continued friendly relation that was never broken or impaired up to 1860."

When in Bloomington, Lincoln often stayed at the Pike House and sometimes delivered political speeches from its balcony. Lincoln biographer Carl Sandburg noted that in the mid-1850s, "though a building boom was going on in Bloomington, its hotels sometimes could not accommodate all comers, and Lincoln, one evening in that city, went canvassing among private houses for a furnished room." Some of Lincoln's most important speeches were delivered in Bloomington. The first was delivered in Bloomington after the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, for which Illinois Senator Stephen A. Douglas was the prime sponsor. Judge Lawrence Weldon recalled: "The first time I met him was in September 1854, at Bloomington, and I was introduced to him by Judge Douglas, who was then making a campaign in defense of the Kansas-Nebraska bill. Mr. Lincoln was attending court and called to see the Judge. They talked very pleasantly about old times and things, and during the conversation, the Judge broadened the hospitalities of the occasion by asking him to drink something. Mr. Lincoln politely declined when the Judge said: "Why do you belong to the temperance society?" He said:

"I do not believe in theory, but I do, in fact, belong to the temperance society, to wit, that I do not drink anything and have not done so for many years."

Shortly after he retired, Mr. J. W. Fell, then and now a leading citizen of Illinois, came into the room with a proposition that Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Douglas have a discussion, remarking that there were a great many people in the city, that the question was of great public importance, and that it would afford the crowd the luxury of listening to the acknowledged champions of both sides. As soon as the proposition was made, it could be seen that the Judge was irritated. He inquired of Mr. Fell, with some majesty of manner: "Whom does Mr. Lincoln represent in this campaign-is he an Abolitionist or an Old Line Whig?"

Mr. Fell replied that he was an Old Line Whig. "Yes," said Douglas, "I am now in the region of the Old Line Whig. When I am in Northern Illinois, I am assailed by an Abolitionist. When I get to the center, I am attacked by an Old Line Whig. And when I go to Southern Illinois, I am beset by an Anti-Nebraska Democrat. I can't hold the Whig responsible for anything the Abolitionist says and can't hold the Anti-Nebraska Democrat responsible for the positions of either. It looks to me like dogging a man all over the State. If Mr. Lincoln wants to make a speech, he had better get a crowd of his own, for I must respectfully decline to hold a discussion with him."

Mr. Lincoln had nothing to do with the challenge except to say he would discuss the question with Judge Douglas. He was not aggressive in defense of his doctrines or enunciation of his opinions, but he was brave and fearless in protecting what he believed was right. The impression he made when I was introduced was his unaffected and sincere manner and the precise, cautious, and accurate mode in which he stated his thoughts, even when talking about commonplace things.

Lincoln had already given a major speech in Bloomington on September 12, arguing for public opposition to the recently passed Kansas-Nebraska legislation that effectively overturned the Missouri Compromise and outlawed slavery in the northern part of the Louisiana Territory. "They ought to make a strong expression against the imposition that would prevent the consummation of the scheme. The people were the sovereigns, and the representatives their servants, and it was time to make them sensible of this genuinely democratic principle. They could get the Compromise restored. They were told they could not because the Senate was [controlled by advocates of] Nebraska [legislation] and would be for years. Then fill the lower House [of Congress] with valid Anti-Nebraska members, which would express the people's sentiment.

And furthermore, that expression would be heeded by the Senate. If this State should instruct Douglas to vote for the repeal of the Nebraska Bill, he must do it, for the 'doctrine of instructions' was a part of his political creed. And he was not sure he would not be glad to vote for its repeal anyhow if it would help him somewhat out of the scrape. It was so with other Senators they will surely improve the first opportunity to vote for its repeal. The people could get it repealed if they resolved to do it."

Fell began pushing for a Bloomington debate between Lincoln and Douglas in 1854. "Mr. Fell never gave up the idea of having a joint debate between Lincoln and Douglas, and he continued to agitate it until four years afterward, it occurred in the contest for the senatorship. I think Mr. Fell, more than anybody else, is entitled to the credit of bringing about the seven joint debates in 1858," recalled James S. Ewing of his Bloomington boyhood.

Bloomington would become the first of three localities in Illinois where Lincoln and Douglas gave speeches together. On September 26, Douglas and Lincoln delivered long speeches on the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Douglas talked in the afternoon. That night, Lincoln delivered his speech in which he rebutted the justifications Douglas had given for legislation and its support in Illinois: "Judge Douglas has said that the Illinois Legislature passed resolutions instructing him to repeal the Missouri Compromise. But Mr. Lincoln, the Judge, when he refers to resolutions of instruction, always gets those that never passed both houses of the Legislature. The Legislature [passed] a resolution, upon this subject which the Judge either needed to remember or choose to read. No man who voted to pull down the Missouri Compromise represented the people, and [the Legislature] of this State never instructed Douglas or anyone else to commit that act. And yet, the Judge had told the people that they were in favor of repealing the Missouri Compromise, and all must acquiesce in his assumption or be denounced as abolitionists. What sophistry is this, said Mr. Lincoln, to contend and insist that you did instruct him to effect the repeal of the Missouri Compromise when you know you never thought of such a thought of it [Cries of 'No! No!!'] — that all the people of Illinois [according to Douglas] have always been opposed to that Compromise when no man will say that he ever thought of its repeal previous to the introduction of the Nebraska bill."

The most notable event in Lincoln's life in Bloomington was the famous "Lost Speech" delivered at the Illinois Republican State Convention at Major's Hall in 1856. The convention had been called by a meeting in Decatur of newspaper editors that Lincoln had attended in February. It took place in the shadow of agitation and violence in Kansas over the spread of slavery to that territory and the beating of Massachusetts Senate Charles Sumner by a South Carolina congressman. At the same time, Sumner sat in his Senate seat. One Bloomington resident, Judge R. M. Benjamin, later wrote: "A great speech requires a righteous cause, an inspiring occasion, and a man who measures up to the full height of the cause and the occasion." Benjamin noted: "That speech was never 'lost.' Its influence and inspiration went with the great men who heard it — men who had no small part in making this continental nation an 'indestructible union' of free states." Attorney Henry Whitney recalled Lincoln's actions as he traveled to and arrived in Bloomington for the convention:

"Judge Davis resided at Bloomington but was then holding Court at Danville, he had invited, to stay at his fine residence just east of town, Archibald Williams, of Quincy, T. Lyle Dickey, of Ottawa, Mr. Lincoln and myself. The Judge did not expect to be, and was not, in fact, at home, during the sitting of the convention."

"Lincoln was to go from the Danville Court direct to Bloomington via Decatur, and he and I agreed that I should meet him at Tolono and accompany him. We stopped at Decatur just before nightfall and put up at a hotel, there being no train North till early next morning. As I remember it now, we did not meet a single chance acquaintance, although this was the County of Lincoln's first residence in Illinois. . . ."

"Early the next morning, we took the train for Bloomington. It had come from Centralia and had but few persons on board. We sat in the rear of the only coach not consecrated to tobacco smoke, and no one was in our part of the car."

"Lincoln was extremely anxious to know if any delegates were on board the train en route to the convention. He requested me to make inquiry in that direction of the few passengers, which I found some excuse for declining to do, so Lincoln himself went to the forward end of the car and gazed through the list as he paced slowly back to where I sat deeply engaged with "The Howadji in Syria." "I really would like to know if any of those men are from down south, going to the convention," said he. "I don't see any harm in asking them," I replied. "I believe I will," said he, at last, and he left me to perform his errand. He returned in fifteen or twenty minutes, his face radiant with happiness. He had found two delegates from Marion County. The point was this: Southern Illinois was thoroughly hostile to "black republican" ideas, and Lincoln's hope was to discern any sentiment down there in that line. It will be recollected by many that one solitary vote was cast for Fremont in Johnson County, but in the large majority of counties in Logan's district, not a single vote was cast against [Democrat James] Buchanan."

"Judge Davis' house was but a few yards from the Illinois Central depot, and on going there, neither of the others had arrived, but when we came to tea in the afternoon, we found Judge [T. Lyle] Dickey, who had preceded us a short time, Mr. [Archibald] Williams not arriving till the night train."

"After dinner, Lincoln proposed that I should go with him to the Chicago & Alton depot, in another part of the town, to see who might arrive from Chicago. On our way, Lincoln stopped at a very diminutive jewelry shop, where he bought his first pair of spectacles for 37½ cents, as I now recollect it. He then remarked that he had got to be forty-seven years old and "kinder" needed them. As we approached the depot, we found ourselves to be late and that the omnibuses were just starting away, full of passengers, several of whom at once recognized and called out to Lincoln."

"As we turned to retrace our steps, Lincoln said to me sotto voce, but enthusiastically: "That's the best sign yet, [Chicago attorney Norman B.] Judd is there, and he's a trimmer."

"It must be borne in mind that our convention was as yet but an experiment, and it was not definitely known how successful it would become. Judd was afterward an applicant for the position of Secretary of the Interior under Lincoln and was, in fact, made Minister to Prussia."

"Throughout all the various steps preceding and during the entire work of the convention, Lincoln was active, alert, energetic and enthusiastic. I never saw him more busily engaged, more energetically at work, or with his mind and heart so thoroughly enlisted."

"The convention assembled in Major's Hall, with Archibald Williams as temporary chairman. When Lawrence County was called, no response came. The Secretary was proceeding with the call when Lincoln arose and exclaimed, anxiously looking all around: "Mr. Chairman, let Lawrence be called again. There is a delegate in town from there, and a very good man he is, too." The call was repeated, but no reply came. The delegate, whose courage failed him at the last moment, in the presence of the Abolitionist contingent, was [future State Auditor] Jesse K. Dubois. He came, indeed, as a delegate, but seeing Lovejoy and other Abolitionists there as cherished delegates, he, through indignation or timidity, stayed away for the time being."

Lincoln acted midwife to the emerging Republican Party. Biographer Michael Burlingame wrote: "Energetically but discreetly, holding no official position other than the chairman of the nominations committee, Lincoln was the master spirit of the convention, managing through some political alchemy to convince former enemies to set aside their differences and cooperate for the greater good. Chicago delegate John Locke Scripps thought that 'no other man exerted so wide and salutary an influence in harmonizing differences, in softening and obliterating prejudices, and bringing into a cordial union those who for years had been bitterly hostile to each other.'" At the end of the day, Lincoln was called on to speak, although he was not on the program.

Whitney recalled: "The afternoon of the convention was, as usual, devoted to speeches, Lincoln being accorded the post of honor, and making the last speech of any consequence-altho' B. C. Cook got in a little speech later. I never in my whole life up to this day heard a speech so thrilling as this one from Lincoln. No one who was present will forget its climax. I have since talked with many who were present, and all substantially concur in enthusiastic remembrances of it."

The audience was composed mainly of old, veteran politicians, whose fancies were not easily beguiled nor readily entrapped into enthusiasm, but when the majestic Lincoln, after reciting the history of the encroachments of the slave power, defined clearly the duties of the hour, and then, with a mien and gesture that no language can describe, exclaimed (referring to threatened secession), "When it comes to that, we will say to our Southern brethren: we won't go out of the Union, and you shan't" the effect was thrilling and indescribable, no language can convey any conception of it. I have never seen such excitement among a large body of men and scarcely ever expect to again.

John L. Scripps, a Chicago Journalist, has given his experience of this most remarkable speech in the following enthusiastic description: "Never was an audience more completely electrified by human eloquence. Again and again, during its delivery, they sprang to their feet upon the benches and testified by long-continued shouts and the waving of hats how deeply the speaker had wrought upon their minds and hearts. It fused the mass of hitherto incongruous elements into perfect homogeneity, and from that day to the present, they have worked together in harmonious and fraternal Union."

The convention adjourned a few minutes later, and as I passed down-stairs with the crowd, Jesse K. Dubois (who had been afraid to respond to the roll-call of counties but who came in later and was nominated for State Auditor) seized me by the arm with a painful grip and made an exclamation to me close to my ear, which I soon afterward repeated to Lincoln.

Of course, he was the lion of the hour. Everybody crowded around him, florid congratulations were as thick as autumnal leaves "that strowed the banks of Vallambrosa:" enthusiastic hand-shaking was the normal State of man., and that "thrilling speech" was the burden of every man's theme, on that occasion. Lincoln got disentangled from the applauding crowd at length. He and I started off in the direction of Judge Davis' house. Still, we immediately diverged into a side street to shake off everybody. As soon as we were out of everyone's hearing, Lincoln, at once, commenced a line of remark upon the extraordinary scene we had just witnessed and whose prime mover he was, at the same time bending his head down to make our conversation more confidential. In a glow of enthusiasm, I said in reply to a question by him: "You know that my statements about your speeches are not good authority, so I will tell you what Dubois, who is not so enthusiastic as I am, said to me as we came out of the hall. He said: 'Whitney, that is the greatest speech ever made in Illinois, and it puts Lincoln on the track for the Presidency.'"

"While I was making this reply, he walked along without straightening himself up for some thirty seconds, perhaps without saying a word, but with a thoughtful, abstracted look, then he straightened up and immediately made a remark about some commonplace subject, having no reference to the subject we had been considering."

The next day one delegate told Lincoln at the train station: "Lincoln, I never swear, but that was the damnedest best speech I ever heard."

There were few press notices of Lincoln's oratory, but the Alton Week Courier reported: "Abraham Lincoln, of Sangamon, came upon the platform amid deafening applause. He enumerated the pressing reasons for the present movement. He was here ready to fuse with anyone who would unite with him to oppose slave power, spoke of the bugbear disunion which was so vaguely threatened. It was to be remembered that the Union must be preserved in the purity of its principles and in the integrity of its territorial parts. It must be 'Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable.' The sentiment in favor of white slavery now prevailed in all the slave state papers except those of Kentucky, Tennessee, Missouri, and Maryland. Such was the progress of the National Democracy. Douglas once claimed against him that Democracy favored more than his principles, the individual rights of man. Was it not strange that he must stand there now to defend those rights against their former eulogist? The Black Democracy were endeavoring to cite Henry Clay to reconcile old Whigs to their doctrine and repaid them with the very cheap compliment of National Whigs." Lincoln scholar Ralph Gary wrote: "Estimates for the crowd size are from five hundred to two thousand. Based on the size of the hall, author Elwell Crissey estimated eleven hundred . . . Being late in the day, most reporters thought the session was over and put up their pens. They probably expected jokes anyway. By the time they realized the importance of what was being said, they were caught up in a spell, became enraptured, and could not write." Other observers have theorized that after the fact, Lincoln questioned the radicalism of what he said and discouraged his journalistic friends from fully reporting it. The Chicago Democratic Press reported:

Never has it been our fortune to listen to a more eloquent and masterly presentation of a subject. I shall refrain from marring any of its proportions or brilliant passages by attempting even a synopsis of it. Mr. Lincoln must write it out and let it go before all the people. For an hour and a half, he held the assemblage spellbound by the power of his argument, the intense irony of his invective, and the deep earnestness and fervid brilliancy of his eloquence. When he concluded, the audience sprang to their feet, cheer after cheer told how deeply their hearts had been touched, and their souls warmed to a generous enthusiasm.

Virtually all who attended the Bloomington convention were impressed by the speech. John G. Nicolay, Lincoln's future presidential Secretary, wrote: "I had the good fortune to be one of the delegates from Pike county in the Bloomington convention of 1856, and to hear the inspiring address delivered by Abraham Lincoln at its close, which held the audience in such rapt attention that the reporters dropped their pencils and forgot their work. Never did nobler seed fall upon more fruitful soil than his argument and exhortation upon the minds and hearts of his enthusiastic listeners." Virtually all of Lincoln's top political associates were in attendance. William H. Herndon, Lincoln's law partner, wrote: "Judd, Yates, Trumbull, Swett, and Davis were there, so also was Lovejoy, who, like Otis of colonial fame, was a flame of fire. The firm of Lincoln and Herndon was represented by both members in person. The gallant William H. Bissell, who had ridden at the head of the Second Illinois Regiment at the battle of Buena Vista in the Mexican war, was nominated as governor. The convention adopted a platform ringing with strong anti-Nebraska sentiments and then and there gave the Republican party it is official christening. The business of the convention being over, Mr. Lincoln, in response to repeated calls, came forward and delivered a speech of such earnestness and power that no one who heard it will ever forget the effect it produced. In referring to this speech some years ago, I used the following rather graphic language: 'I have heard or read all of Mr. Lincoln's great speeches, and I give it as my opinion that the Bloomington speech was the grand effort of his life. Heretofore he had simply argued the slavery question on the grounds of policy, the statesman's grounds, never reaching the question of the radical and the eternal right. Now he was newly baptized and freshly born. He had the fervor of a new convert. The smothered flame broke out, enthusiasm unusual to him blazed up, his eyes were aglow with inspiration, he felt justice, his heart was alive to the right, his sympathies, profound for him, burst forth, and he stood before the throne of the eternal right. His speech was full of fire and energy, and force. It was logic. It was pathos, enthusiasm, justice, equity, truth, and the right set ablaze by the divine fires of a soul maddened by the wrong. It was hard, heavy, knotty, gnarly, and backed with wrath. I attempted for about fifteen minutes, as was usual with me then, to take notes, but at the end of that time, I threw pen and paper away and lived only in the inspiration of the hour. If Mr. Lincoln was six feet, four inches high usually, at Bloomington that day, he was seven feet and inspired at that. From that day to his death, he stood firm in the right. He felt his great cross, had his great idea, nursed it, kept it, taught it to others, in his fidelity bore witness of it to his death, and finally sealed it with his precious blood.' The preceding paragraph, used by me in a lecture in 1866, may to the average reader seem vivid in description, besides inclining to extravagance in imagery. Yet, although more than twenty years have passed since it was written, I have never seen the need to alter a single sentence. I still adhere to the substantial truthfulness of the scene as described. Unfortunately, Lincoln's speech was never written nor printed, and we are obliged to depend on its reproduction upon personal recollection."

Not all of Lincoln's Bloomington speeches were so successful. Lincoln delivered his first "Lecture on Discoveries and Inventions" in Bloomington at Centre Hall in 1858. Although a large crowd attended that lecture when in 1859, he attempted to give the lecture a second time, few showed up.

|

| Lincoln-Douglas Debates, 1858. |

Bloomington figured prominently in Lincoln's 1858 campaign against Senator Stephen A. Douglas, which began with Lincoln's House Divided speech in Springfield in June. Bloomington attorney Leonard Swett was Lincoln's close legal and political associate. He recalled: "I was inclined at the time to believe these words were hastily and inconsiderately uttered, but subsequent facts have convinced me they were deliberate and had been matured. Judge T. L Dickey says that at Bloomington at the first Republican Convention in 1856, he uttered the same sentences in a Speech delivered there and that after the meeting was over, he (Dickey) called his attention to these remarks. Lincoln justified himself in making them by stating they were true, but finally, at Dickey's urgent request, he pronounced that he would not repeat them for his sake or upon his advice. In the Summer of 1859, when he was dining with a party of his intimate friends at Bloomington, the subject of his Springfield speech was discussed. We all insisted it was a great mistake, but he justified himself and finally said, "Well, Gentlemen, you may think that Speech was a mistake, but I never have believed it was, and you will see the day when you will consider it was the wisest thing I ever said."

Senator Douglas, campaigning for a third term in the Senate, came to Bloomington in mid-July 1858 after kicking off his campaign in Chicago. Paul M. Angle wrote: "Bloomington extended a boisterous welcome. After an enthusiastic greeting at the station, Douglas was seated in an open carriage and escorted by the Bloomington Rifles and a band to the London House. That evening he spoke for two hours from a platform in the courthouse square." Harry Pratt wrote: "Douglas arrived in Bloomington July 16, 1858, in a private car attached to the Illinois Central train from Chicago. The private car caused much comment in the Republican city as some two thousand gathered at the station to greet him. The roar of the cannon on the flat car attached to Douglas' train was answered by the town artillery. . . . That night, Douglas spoke in the courthouse square. Lincoln sat on the platform and listened to the long address, and late as it was when he finished, the crowd called loudly for him. He held back for a while, but when he came forward, his friends gave him three rousing cheers much louder than those given for Judge Douglas. He told the crowd he would soon revisit them and make a speech, but that 'this meeting was called by the friends of Judge Douglas, and it would be improper for me to address it.'" After asserting that blacks were not and could be citizens, Douglas concluded his address that day:

"I thank you kindly for the patience with which you have listened to me. I fear I have wearied you. I have a heavy day's work before me tomorrow, and I have several speeches to make. My friends, in whose hands I am, are taxing me beyond human endurance, but I shall take the helm and control them hereafter. I am profoundly grateful to the people of McLean for the reception they have given me and the kindness with which they have listened to me. I remember when I first came among you here, twenty-five years ago, that I was prosecuting attorney in this district and that my earliest efforts were made here when my deficiencies were too apparent, I am afraid, to be concealed from anyone. I remember the courtesy and kindness with which I was uniformly treated by you all, and whenever I can recognize the face of one of your old citizens, it is like meeting an old and cherished friend. I come among you with a heart filled with gratitude for past favors. I have been with you but little for the past few years on account of my official duties. I intend to visit you again before the campaign is over. I wish to speak to your whole people. I want them to pass judgment upon the correctness of my course and the soundness of the principles I have proclaimed. I cannot ask for your support if you disapprove of my principles. Suppose you believe that the election of Mr. Lincoln would contribute more to preserving the country's harmony and perpetuating the Union and more to the prosperity, honor, and glory of the State. In that case, it is your duty to give him the preference. If, on the contrary, you believe that I have been faithful to my trust and that by sustaining me, you will provide greater strength and efficiency to the principles I have expounded, I shall be grateful for your support. I renew my profound thanks for your attention.

In early September, Lincoln returned to Bloomington to give a campaign speech. Lincoln's subject, as it had been since 1854 and would be until 1860, was opposition to the spread of slavery. By then, Lincoln had engaged Sen Douglas in two famous series of seven debates. Attorney R. M. Benjamin spoke of that day decades later:

"Some of you, now here, have heard in this city, as I have, able political speeches made by James G. Blaine, Benjamin Harrison, Lyman Trumbull, John A. Logan, Richard J. Oglesby, John M. Palmer, Owen Lovejoy, Robert Q. Ingersoll, Leonard Swett, and Lawrence Weldon, yet I venture to say that none of you can, to-day, state the line of any one of those speeches."

"But from Lincoln's other speeches-always on the same text-can be formed some idea of the clear statements of facts and principles, the convincing logic, the impressive manner, the power and eloquence of his Major's Hall speech."

"Some of you, as I did, heard Lincoln speak in the Court House Square on the afternoon of September 4, 1858. The proceedings on that day were reported in the Weekly Pantograph of September 8. Let me recall the long procession formed under the direction of William McCullough, Chief Marshal, and Ward H. Lamon, Charles Schneider, James O'Donald, and Henry J. Eager, Assistant Marshals. You saw that procession march to the residence of Judge Davis, there receive Lincoln, and then counter-march down Washington Street to the public square."

"You saw the banners bearing these mottoes, 'Our country, our whole country and nothing but our country,' 'The Union-it must be preserved,' 'Freedom is national-slavery is sectional,' 'Honor to the honest. God defend the right.'"

"You then saw above the north door of the old brick Court House the representation of a ship in a storm and underneath the words, 'Don't give up the ship-give her a new pilot.'"

"The ship came safely into port, and now-this moment-there flashes across your minds, the lines of Walt Whitman's best poem, 'O, Captain, My Captain.'"

"On that day, September 4, 1858, over fifty years ago, fewer than seven thousand of you were in and around the public square. The Court House, Phoenix block, Union block, and the sidewalks next to the square were alive with people. Dr. Isaac Baker was the President of the Day, and Leonard Swett made the reception speech."

"Lawrence Weldon, then of Clinton, and Samuel C. Parks, of Lincoln, spoke in the evening.

You who heard Lincoln then listen again to a few words he spoke regarding the irrepressible agitation of slavery and his own position as to slavery in the slave-holding States and freedom in the Territories.

Said he: 'It is not merely an agitation got up to help men into office . . . The same cause has rent the great Methodist and Presbyterian churches asunder. . . . It will not cease until a crisis has been reached and passed. When the public mind rests on believing that slavery is on the course of ultimate extinction, it will become quiet. We have no right to interfere with slavery in the States. We only want to restrict it where it is. We had never had an agitation except when it was endeavored to spread it. . . . The trainers of the Constitution prohibited slavery (not in the Constitution, but the same men did it) north of the Ohio River where it did not exist, and did not prohibit it south of that River where it did exist. . . . I fight slavery in its advancing phase, and wish to place it in the same attitude that the framers of the government did.'"

This was a clear statement that the agitation of the slavery question, which had rent in twain the churches, would not cease until the public mind should rest in the belief that slavery was in the course of ultimate extinction-a clear statement that we of the North had no right to interfere with slavery in the Southern States, but should resist its further advancement into the national Territories.

A highlight of the 1858 confrontations was the second debate at Freeport on August 27. On September 3, at a meeting in Bloomington at Judge Davis's home before the third debate, Lincoln told political associates: "Gentleman, I am going to put to Douglas the following questions, and the object of this meeting is to have each of you assume you are Douglas and answer them from his standpoint."

Following his defeat in 1858, Lincoln returned to the law but decided to give a series of out-of-Illinois speeches that boosted his national visibility. In early April 1859, Lincoln attended a meeting of the Republican State Central Committee in Bloomington. After it, Lincoln wrote former Lieutenant Governor Gustave Koerner about actions to reach out to German-American voters: "Reaching home last night, I found your letter of the 4th. The meeting of the Central Committee was at Bloomington and not here. I was attending court and, in common with several other outsiders, one of whom was Judge Trumbull, was in conference with the Committee to some extent. Judd privately mentioned the subject you wrote to me and requested me to prepare a resolution, which I did. When I brought in the resolution and read it to the Committee and others present in an informal way, Judge Trumbull suggested that it would be better to select some act of our adversaries rather of our own friends upon which to base a protest against any distinction between native and naturalized citizens, as to the right of suffrage. This led to a little parley. I was called from the room, the thing passed from my mind, and I do not now know whether anything was done about it by the Committee. Judge Trumbull will be in Belleville when this reaches you, and he can probably tell you all about it. Whether anything was done or not, something must be done the next time the Committee meets, which I presume will be before long." He added: "I am right glad the Committee put in operation our plan of organization which we started here last winter. They appointed Mr. Fell of Bloomington as Secretary."

Bloomington residents took a prominent role in promoting Lincoln for the Republican nomination for President. Jesse Fell raised the possibility in the fall of 1858. Fell's persistence in pushing for a debate was recalled by a story of him meeting Mr. Lincoln at Judge Davis's office one day: "Oh, here's Fell again. No, I can't do it. But it's no use talking. You'll have me before you go away." Years later, Fell recalled Lincoln telling him: "Oh, Fell, what's the use of talking of me for the presidency, whilst we have such men as Seward, Chase and others, who are so much better known to the people, and whose names are so intimately associated with the principles of the Republican party. Everybody knows them. Nobody, scarcely outside of Illinois, knows me. Besides, it is not, as a matter of justice, due to such men who have carried this movement forward to its present status, despite fearful opposition, personal abuse, and hard names? I really think so." After Fell presented additional arguments, Mr. Lincoln said: "Well, I admit the force of much that you say, and admit that I am ambitious and would like to be President. I am not insensible to the compliment you pay me and the interest you manifest in the matter, but there is no such good luck in store for me as the presidency of these United States. Besides, nothing in my early history would interest you or anybody else, and as Judge Davis said, 'it won't pay.' Good night." Fell nevertheless convinced him to provide material that he turned into a biography of the potential candidate. Journalist Walter Stevens observed: "With his newspapers instincts and inclination to promotion methods, Mr. Fell put in early operation at Bloomington a press bureau. At the instance of Mr. Fell, and as a result of not a little persuasion, Mr. Lincoln sat down at a table in the courtroom at Bloomington and wrote his autobiography, which is historic. He did this in 1859. The first use Mr. Fell made of the sketch was to send a copy of it to a paper in Pennsylvania, his early home, with the information that this was the man whose joint debates with Douglas had aroused the whole country and the man whose name Illinois would, in all probability, present to the Republican Convention of 1860.

In early 1860, Lincoln's friends, spurred on by the favorable publicity that Lincoln's Cooper Union speech received, worked steadily and stealthily to boost Lincoln's candidacy for the Republican presidential nomination. Historian Harry E. Pratt wrote:" While attending his last circuit court in Bloomington, April 10, 1860, Lincoln made his previous long political speech before being nominated for President by the Republican National Convention in Chicago, May 18, 1860. Despite the rain and the mud, between 1,200 and 1,500 packed into Phoenix Hall on the south side of the courthouse square to hear a speech that was 'clear, appropriate, forcible and conclusive on every point.' The newspaper called Mr. Lincoln probably the fairest and most honest political speaker in the country, adding that 'he convinces the understanding by arriving at legitimate and unavoidable sequences, he wins the hearts of his hearers by the utmost fairness and good humor."

Judge Davis and Swett were among the Bloomington residents who led efforts at the Republican National Convention in Chicago in May to get Lincoln the Republican presidential nomination Henry Clay Whitney recalled the reaction after Mr. Lincoln wired his supporters, "Make no contracts that will bind me." According to Whitney: "Everybody was mad, of course. . . . What was to be done? The bluff Dubois said: 'Damn Lincoln!' The polished Swett said, in mellifluous accents: 'I am very sure if Lincoln was aware of the necessities.' The critical Logan expectorated viciously and said, 'The main difficulty with Lincoln is' Herndon ventured, 'Now, friend, I'll answer that.' But Davis cut the Gordian knot by brushing all aside with: 'Lincoln ain't here and don't know what we have to meet, so we will go ahead as if we hadn't heard from him, and he must ratify it.'"

Lincoln was nominated on May 18. Harry E. Pratt wrote: "News of the selection reached Bloomington about one o'clock. The courthouse bell clanged, a crowd gathered, and General Gridley opened with the first speech, followed by Brier, Wickizer, Harvey Hog, and John M. Scott. In conclusion, Captain Enright gave his Bloomington Guards the command, and a 100-gun salute roared out over the crowded square. The next night's ratification meeting in Phoenix Hall was addressed by Mr. George G. Fogg of New Hampshire, Secretary of the National Republican Committee, and Mr. Ballestier of New York, both members of the Chicago Convention." They apparently stopped in Bloomington on their way to Springfield officially to inform Lincoln of his nomination.

Lincoln last visited Bloomington on November 21, 1860, while on the way to Chicago as president-elect, where he would meet Vice President-elect Hannibal Hamlin for the first time. Lincoln spoke briefly: "FELLOW-CITIZENS OF BLOOMINGTON AND MCLEAN COUNTY, I am glad to meet you after a long separation than has been common between you and me. I thank you for your good report on the election in Old McLean. The country's people have again fixed up their affairs for a constitutional period. By the way, I think very much of people, as an old friend said he thought of women. He said when he lost his first wife, who had been a great help to him in his business, he thought he was ruined, that he could never find another to fill her place. At length, however, he married another, who he found did quite as well as the first, and his opinion now was that any woman would do well who was well done by. So I think of the whole people of this nation—they will ever do well if well done. We will try to do well by them in all parts of the country, North and South, with entire confidence that all will be well with all of us."

In February 1861, Lincoln left Springfield for Washington and never saw Bloomington again. During the Civil War, wrote Pratt, "Union sentiment in Bloomington was strong, though Copperheads and Sons of Liberty were numerous. The Bloomington Times was conducted by D.J. and F.F. Snow with such marked expressions of sympathy for the Southern states that the 94th Regiment of Illinois Volunteers, the McLean County regiment, abetted by prominent citizens, destroyed the office and press and with them the paper."

Lincoln's friends only sometimes made things easy for the man they had helped elect President. Lincoln Scholar Harold Holzer wrote that President-elect "Lincoln's own closest advisors, Norman Judd, David Davis, and Leonard Swett, made things more difficult still by converging into town [Springfield] and kicking up a huge 'strife' of their own for 'supremacy' within the inner circle, causing Lincoln' great tribulation.'" Unlike many of Lincoln's Illinois friends, Jesse Fell understood Lincoln's political dilemmas, especially between factions of the Illinois Republican Party headed by Bloomington's Davis and Chicago's Norman B. Judd: "Illinois having the President, I feel quite confident that 99 percent of the politicians of the country — who have 'no axes to grind,' would say 'that's enough — no first-class appointments should be given her.' What I desire, however, most to say, in this connexion, is, don't, if you can well avoid it, increase the feuds, already too great between the two elements of which our party is mainly composed, by appointing to such a position the representative of either." Fell added: "By giving neither Judd nor Davis appointments, you can not only have a better opportunity to satisfy the claims of other States, but you will keep down a vast deal of ill feeling here at home."

Leonard Swett wrote of Mr. Lincoln's Illinois friends: "They all had access to him, they all received favors from him, and they all complained of bad treatment, but while unsatisfied, they all had 'large expectations,' and saw in him the chance of obtaining more than from anyone else whom they could be sure of getting in his place. He used every force to the best possible advantage. He never wasted anything and would always give more to his enemies than to his friends because he never had anything to spare. In the close calculation of attaching the factions to him, he counted upon the abstract affection of his friends as an element to be offset against some gift with which he must appease his enemies. Hence, there was always some truth in charge of his friends that he failed to reciprocate their devotion with his favors. The reason was that he had only just so much to give away — 'He always had more horses than oats.'" Attorney Henry Clay Whitney wrote how Lincoln handled the ambitions of his Illinois friends, particularly Judge David Davis, who seemed to aggravate Lincoln in 1861 with his aggressive suggestions regarding patronage:

"Judge Davis possessed an energetic, restless spirit, and as soon as Lincoln had received the nomination (which had been achieved largely through the efforts of the Judge), he thought he ought to be consulted and counseled with as to the appointments and policy of the incoming administration. But Lincoln didn't seem inclined to that view of the case at all, in fact, the only man in our old circuit that he consulted with at all on national subjects was Leonard Swett, and there were but two other Illinois men whom he thus honored, viz.: Norman B. Judd and Elihu B. Washburne. His old townsmen and friends he gave the go-by to entirely, he held no conferences, took no advice, and sought no counsel from either Herndon, Logan, Stuart, Hatch or Dubois, two of them had been his partners, and Herndon still was so, and the latter had been one of the architects and builders of Lincoln's political fame. Davis tried in various ways to push his schemes, the principal of them being to get his cousin, H. Winter Davis, installed as a cabinet officer, and, in so doing, made himself offensive to Lincoln, who knew of it in many ways, in fact, Davis had a wonderful gift of loquacity, and as he lived but sixty miles distant, and saw many persons who immediately thereafter saw Lincoln, the latter could not fail to be fully advised of Davis' animus and designs, and it had not gone on long till it was very offensive to the former, so he took the Lincolnian mode of counteracting it, thus: among others who came to see Lincoln was [New York Republican boss] Thurlow Weed, and Davis somehow managed to 'button-hole' him, and (without seeming to have any personal bias or desire) indoctrinated him with some of his ideas: and with the result that when this wily old intriguer saw the President, and the latter asked his distinguished guest whom he had better name as Secretary of War, the reply was the echo of his recent Bloomington conference, he said: 'Henry Winter Davis.' Here was Lincoln's opportunity to silence Davis, for he knew that Weed would tell it as an idle joke and that it would stir the capacious bosom of the Judge to its profound depths, so said: 'Oh! I see Davis (meaning the Judge) has been posting you up: he has Davis on the brain: the east shore of Maryland must be a good place to emigrate from. That puts me in mind of an old feller who was once testifying in a case and, on being asked his age, replied, 'Fifty-three:' the Judge, who knew him to be much older, cautioned him and re-repeated the question: the Judge then threatened him with punishment if he persisted in his mendacity, to which the witness responded: 'You are figuring in the time I lived on the eastern shore of Maryland, that doesn't count.'" It will be known that that is where the Judge came from, a fact of which he was very vain for some reason or other. While Lincoln was apparently regaling Weed with a little story, he was really serving notice on the Judge that his meddlesome ways were not appreciated and amounted to nothing."

President Lincoln's Bloomington friends, like his friends in Springfield, had reason to complain of the patronage they received at his hands. Attorney Henry Clay Whitney recalled meeting with President Lincoln in late July 1861 after the first major battle of the Civil War: "He was apparently devoid of care, for the time being, I remarked this with gratulation, to which he replied, his face becoming sad for a moment: 'I have trouble enough when I last saw you I was having little troubles, they filled my mind full, since then I have big troubles, and they can do no more.' Said he: 'what do you think has annoyed me more than any one thing?' I replied: 'Bull Run, of course.' 'I don't mean,' said he, 'an affair which is forced by events and which a single man cannot do much with, but I mean of matters wholly mine to manage. Now, I will tell you, the fight over two post-offices — one at our Bloomington, and the other at __________, in Pennsylvania (I think),' and he told me at length of the various elements in those struggles — being quite equally balanced — which had disturbed him so much."

Mr. Lincoln liked to escape from the pressures of his job in social conversation. He grew annoyed when social pleasantries turned to political pressure. Whitney violated this rule in July 1861 when his conversation with Lincoln turned to Judge David Davis. "You ought to make him a Supreme Judge," said Whitney. "To this bit of vicarious electioneering, Lincoln vouchsafed no response at all but was thoughtful and silent for a few moments when he started out on a new subject, thus clearly rebuking me for obtruding office-seeking politics on his social pastime." However, Leonard Swett was indefatigable in pressing Lincoln to appoint fellow Bloomington attorney Davis to the Supreme Court, arguing that he (Swett) would relinquish any favors claims to get Davis appointed and that Davis was owed the post for his role in Lincoln's nomination. In 1887, Swett recalled: "Judge Davis was about fifteen years my senior. I had come to his circuit at the age of twenty-four, and between him and Lincoln, I had grown up leaning in hours of weakness on their own great arms for support. I was glad of the opportunity to put in the mite of my claims upon Lincoln and give it to Davis, and have been glad I did it every day since." Close as Lincoln was to Davis, Davis later complained that even when he ran for Judge of the Eighth Circuit in 1848, Lincoln had not supported his candidacy over Benjamin Edwards, a relative of Lincoln's wife. "I had done Lincoln many favors — Electioneered for him — spent money for him — worked for him — toiled for him — still he wouldn't move. Lincoln, I say, again and again, was a peculiar man." In the summer of 1862, Lincoln finally rewarded his old Bloomington friend with a nomination to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Swett worried about Lincoln's reelection and warned the President about Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase's competing presidential ambitions. In 1864, Swett asked President Lincoln if he thought Americans would reelect him: "Well, I don't think I ever heard of many being elected to an office unless someone was for him."

Complied by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

,%20Chicago%20merchant%20and%20philanthropist.png)

.jpg)