Chicago's Agatite Avenue (4432N - 800W to 8642W).

The street name in Chicago, as in most cities and towns in America, named streets, roads, and boulevards after people (Presidents to Locals), places, milestones, honors, etc.

"Agatite" is not a word (Google Search Results: Real Estate/Apartments on Agatite Avenue, and there were no search results other than as a street name. Secondly, there doesn't seem to be anybody famous, infamous, or obscure person by that name in Chicago history. We're famous for our downtown streets named after the Presidents of the United States, Alphabet Town, Letter Town, and last but not least, Number Town.

The street is named after gypsum clay cement/plaster manufactured by the Agatite Cement Plaster Company from Kansas City, Missouri. Loose gypsum earth, known as agatite, is stripped-mined, surface downward. It's used to produce a plaster substitute at a reduced cost, creating a pleasing exterior architectural effect. The Agatite only needed to last a short time since it would all be razed after the fair closed.

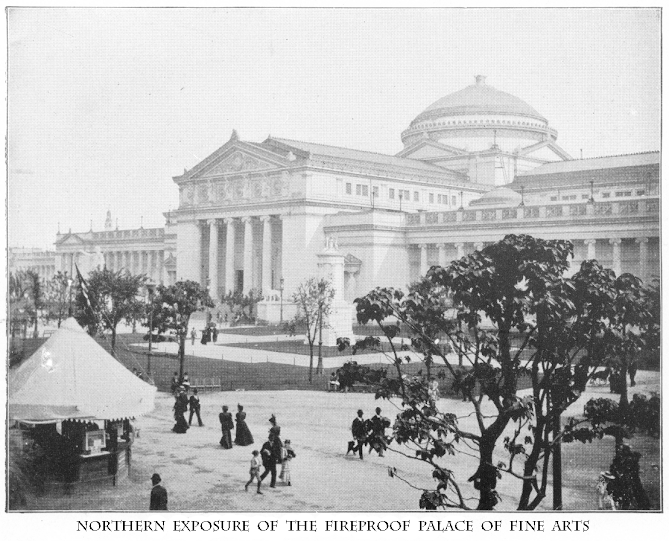

Agatite was used on the exteriors of the Chicago 1893 World's Columbian Exposition Buildings, hence the nickname "The White City." All buildings were built as temporary structures, and Agatite saved a lot of money, making the fair a spectacle to behold.

The Fair's Board of Directors enticed other countries to display their antiquities, fine arts, historical documents, and priceless items in a 'fireproof' and (24/7) secured building. The "Palace of Fine Arts" building (today's Museum of Science and Industry) was filled wall-to-wall and top-to-bottom.

Agatite is of a light ash-gray color. Its natural consistency is about that of hard plastic clay. When calcined (calcined clay is a popular soil amendment used on baseball infields for water management) it assumes a form. When mixed with water it sets as does cement. There needs to be ample time between mixing the mortar to be applied to its intended use to set.Agatite does not differ widely in composition from the Great Pyramid of Giza (aka Pyramid of Cheops) Egypt. The cement runs higher in sulphate than lime and lower in iron oxide.Climates like Egypt and Mexico permit Agatite for exterior use. It was used in Southern States on brick, stone or wooden structures. Agatite produces a pleasing architectural effect at a low cost. It was used as an outside covering of the walls of the World’s Fair Buildings at Chicago which, however, were temporary structures.

Thousands of tons of Agatite Cement Plaster were used in plastering the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition white Agatite (Stucco look-al-link) covered buildings in Chicago.

Agatite was also used on most White City Amusement Park buildings at 63rd & South Parkway (Martin Luther King, Jr. Drive) in Chicago.

|

| A 1905 Bird’s Eye View of White City Amusement Park, Chicago. CLICK THE IMAGE FOR A LARGE PICTURE. |

sidebar

Streetwise Chicago's Book about the History of Chicago Street Names is considered the bible on this subject. Streetwise says, "Agatite street's name is a mystery."

SUGGESTED READING:

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.