Amling's Haunted House opened at 8900 W. North Avenue, on the SW corner of 1st and North Avenues in Melrose Park, Illinois, for Halloween in 1950 and is believed to be the first of its kind in the U.S., said Donna Amling, whose husband is a descendant of the family that founded Amling's Flowerland, the chain of flower shops. Houses of horror have never been the same since.

When it first opened in 1950, it actually was a haunted pirate ship, then later turned into a haunted house.

This may be hard to believe given the blood, guts, and gore in Hollywood today, but once upon a time gorillas were scary. A man in a giant ape costume would stand behind bars at the Amling's Haunted House and when timid visitors approached, the creature's sudden roar startled them in a way they would remember for decades.

"It was just the right impact at the right time," said Bob Paolicchi, whose parents took him to the well-known attraction at North and 1st Avenues in the 1950s and who returned there with his own children in the 1980s. "It was a rite of passage."

At the time, Halloween wasn't as commercialized as it is today, and families didn't have many options when it came to getting their children into the spooky spirit.

So under the leadership of Otto Amling, son of the company's founder, employees at Amling's began a haunted house they hoped would bring extra customers to the greenhouse.

"There's a bunch of haunted houses nowadays, but in those days it was unheard of," said Tim Sandvoss, Otto Amling's grandson. "It was so successful that they just kept going and it got bigger and bigger."

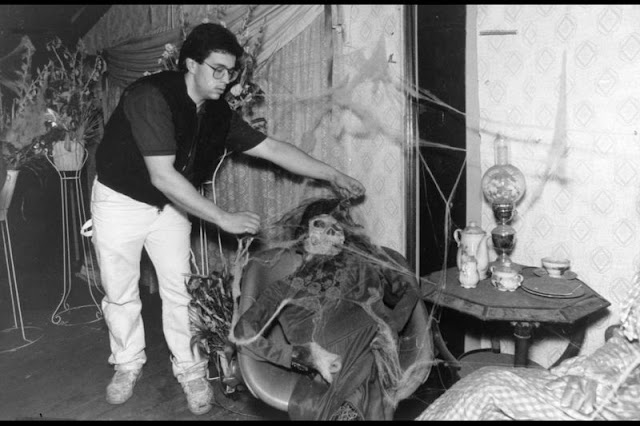

It started as a 25¢ tour of a darkened building with scary scenes and grew to use black lights and live witches, other ghoulish characters like Dracula. The gorilla was a perennial favorite. Some patrons remember getting the choice of doors to open, with monsters jumping out if you picked the right—or wrong—one.

The scares never required chain saws or even a drop of fake blood. "Blood didn't really have anything to do with it," Sandvoss said. "This was clean excitement."

In the early years, the haunted house was operated mostly by nursery employees, but as it grew and became more popular, Amling's teamed up with local churches and charities to send volunteers to help raise money for their causes.

The haunted house expanded to include stagecoach and carnival rides, Sandvoss said. The haunted house would open in late September and people would line up every night through Halloween.

After making it through, visitors were rewarded with an "Amling's Brave Heart Award" button. Some celebrated by buying a cup of hot cider, Sandvoss said.

Over the years, Amling's garden stores changed ownership a few times, mostly between family and longtime friends. The haunted house remained open because owners always realized how treasured it was in the community.

Paolicchi, who grew up in Berwyn and later moved to Westmont, cherishes memories of visiting Amling's Haunted House with his parents, cousins, and younger sister. His sister would grab his hand for dear life. Afterward, they would pick out a pumpkin that his dad would carve at home. "That was the beginning of Halloween season for you," said Paolicchi. "It was what we did as a family." Paolicchi went on to become principal at several schools in the western suburbs, and he took his own children to Amling's at Halloween. He'd love to take his granddaughter, but the haunted house was no more.

Sandvoss said owners let it go in the late 1970s or early 1980s, plagued by the cost of insuring such a thrill-inducing experience.

About a decade later, Donna Amling was shopping with her daughter at a vintage shop and saw the tiny orange "Amling's Brave Heart Award" button for sale. She bought it for $1 and keeps it as a memento. "It's kind of fun to have things that have your name," she said.

by Vikki Ortiz

Edited by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.