Twenty-one Chicago firefighters were crushed to death when a wall collapsed. Before September 11, 2001, the Stockyard tragedy was the deadliest building collapse involving firefighters in the nation's history.

When the fire broke out, it was uncontrollable from the start. It required so many firemen so quickly and couldn’t be put out.

Long before 1910, fires were a common occurrence at the Union Stockyards. Inside these plants were flammables like grease and wood. All it took was a spark, or, in the case of the infamous Stockyard fire, a shorted electrical socket.

It was a cauldron ready to explode, and that’s what it did.

|

| Nelson Morris Warehouse № 7, at the 4300 block of South Loomis Street. |

|

| Firefighters battling the Morris & Co. fire in the Union Stockyards. |

At 5:05 AM, Chief Fire Marshal James Horan arrived on the scene. Horan ordered firefighters from two truck companies — № 11 and № 18 — to ax open the plant’s door. And he had two other men check the condition of the wooden canopy.

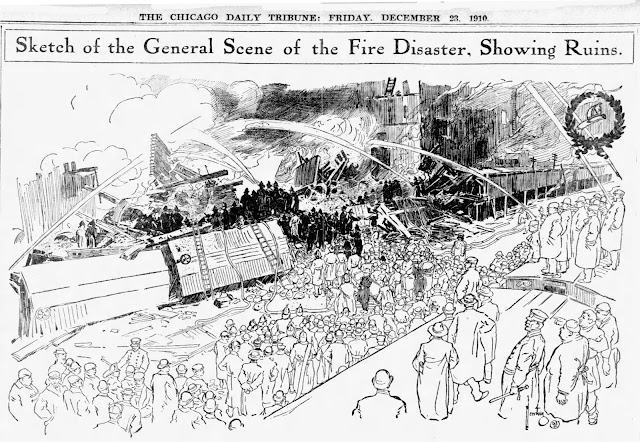

Smoke blinded the firefighters. Intense heat smothered them. They fought on. Before the building collapsed, there was little warning — just a “deep groan” from within the burning plant. The force of the collapse was so great it not only crushed the canopy, but it knocked several of the boxcars clean off the tracks and onto their sides.

The blaze was extinguished at 6:37 AM on December 23rd. The disaster left 19 widows and orphaned 35 children three days before Christmas.

Local news accounts at the time described the macabre scene in detail, including how the bodies of many of the dead were found buried in the rubble amid hog meat that had been stored in the building. It took 17 hours to pull all the bodies from the ruins.

Left in the wake of this tragedy, just days before Christmas, were 19 widows and 35 orphaned children. Contributions raised for the families of the fallen firefighters grew into a controversy pitting the widows against others led by Harlow Higinbotham, who wanted to "manage" the $211,000 in funds for the grieving families rather than distribute the money directly to the widows, parents, and families.

It was said that Higinbotham had earlier kept some of the money intended for the widows and orphans of firemen killed in the 1893 Chicago World's Fair Cold Storage Fire. This would not happen again because the widows' sued, and their case ended up in court, where the judge found in their favor, allowing the widows to control the distribution of the funds.

The deceased was buried within a few days, and some of the funerals were held on Christmas Day.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.