In historical writing and analysis, PRESENTISM introduces present-day ideas and perspectives into depictions or interpretations of the past. Presentism is a form of cultural bias that creates a distorted understanding of the subject matter. Reading modern notions of morality into the past is committing the error of presentism. Historical accounts are written by people and can be slanted, so I try my hardest to present fact-based and well-researched articles.

Facts don't require one's approval or acceptance.

I present [PG-13] articles without regard to race, color, political party, or religious beliefs, including Atheism, national origin, citizenship status, gender, LGBTQ+ status, disability, military status, or educational level. What I present are facts — NOT Alternative Facts — about the subject. You won't find articles or readers' comments that spread rumors, lies, hateful statements, and people instigating arguments or fights.

FOR HISTORICAL CLARITY

About half of Dunning's patients suffered from "chronic

mania," according to the asylum's annual report for 1890. Other patients had

conditions described as melancholia, impulsive insanity, monomania, and circular

insanity. The doctors listed masturbation as one of the most common "exciting

causes" of insanity among Dunning's male patients. According to the report,

other patients had become insane as a result of religious excitement, domestic

trouble, spiritualism, sunstrokes, disappointment in love, alcohol, abortion,

narcotics, puberty, and overwork.

When I write about the INDIGENOUS PEOPLE, I follow this historical terminology:

- The use of old commonly used terms, disrespectful today, i.e., REDMAN or REDMEN, SAVAGES, and HALF-BREED are explained in this article.

Writing about AFRICAN-AMERICAN history, I follow these race terms:

- "NEGRO" was the term used until the mid-1960s.

- "BLACK" started being used in the mid-1960s.

- "AFRICAN-AMERICAN" [Afro-American] began usage in the late 1980s.

— PLEASE PRACTICE HISTORICISM —

THE INTERPRETATION OF THE PAST IN ITS OWN CONTEXT.

In 1851, the Cook County poor farm was established in the town of Jefferson, Illinois, about 12 miles northwest of Chicago. The farm comprised 160 acres of moderately improved land and was formerly owned by Peter Ludby, who purchased it in 1839. By November of 1854, the county poorhouse was nearly finished. The building was of brick, three stories high and basement, and cost about $25,000 ($706,000 today). Additional land was purchased in 1860 and in 1884. In 1915, the land consisted of 234 acres.

The old insane department was of brick, with small barred windows, iron doors, and heavy wooden doors outside, with apertures and hinged shutters for passing food. The cells were about seven by eight feet; they were not heated, except by a stove in the corridor, which did not raise the temperature in some of them above freezing point; the cold, however, did not freeze out the vermin with which the beds, walls, and floors were alive with these scurrying critters. The number of cells in this department was 21, 10 on the lower floor and 11 on the upper floor; many contained two beds.

The old insane department was of brick, with small barred windows, iron doors, and heavy wooden doors outside, with apertures and hinged shutters for passing food. The cells were about seven by eight feet; they were not heated, except by a stove in the corridor, which did not raise the temperature in some of them above freezing point; the cold, however, did not freeze out the vermin with which the beds, walls, and floors were alive with these scurrying critters. The number of cells in this department was 21, 10 on the lower floor and 11 on the upper floor; many contained two beds.

The complex occupied 320 acres of land between Irving Park Road and Montrose Avenue, stretching west from Narragansett Avenue to Oak Park Avenue.

For a long time, Chicagoans were scared of Dunning. The very name "Dunning" gave them chills. People were afraid they would end up in that place.

For a long time, Chicagoans were scared of Dunning. The very name "Dunning" gave them chills. People were afraid they would end up in that place.

Today, the Chicago neighborhood looks like a middle-class suburb on the city's Far

Northwest Side. "If peace and quiet are what

you seek, look no further than Dunning," the Chicago Tribune wrote in 2009.

Some of the area's younger residents have no idea what used to be there: an

insane asylum, a home for the city's poorest people, and cemeteries where the

poor were buried.

"I grew up in this area," says Michael Dotson, 29.

"I've passed by this vicinity a hundred times and never knew anything about

it." Dotson recently stumbled across a website that mentioned the old Dunning

asylum. And then he saw a headline claiming that 38,000 bodies might be lying

underneath the old Dunning grounds, their burial places unmarked.

That prompted Dotson to pose this question:

What’s the history behind Cook County’s former Dunning Insane Asylum and the people buried near there?

It's a long history with many dark chapters. Curious City

can't detail the entire history, so we focused on finding out who lived at

Dunning — and who is still lying in Dunning's unmarked graves. In both life and

death, the people who ended up at Dunning were some of Chicago's least

fortunate residents.

Here's how historian Perry Duis describes Dunning's reputation

in his 1998 book "Challenging Chicago":

For many generations of Chicago children, bad behavior came to a halt with a stern warning: “Be careful, or you’re going to Dunning.” The prospect sent shivers down the spines of youngsters, who regarded it as the most dreaded place imaginable.

Chicago resident Steven Hill, who is 60, recalls: "It was a term used in the '50s and '60s — 'If you and your brothers and sisters don't

behave, we'll send you to Dunning.' And that used to scare kids because they

knew that it was a mental institution."

|

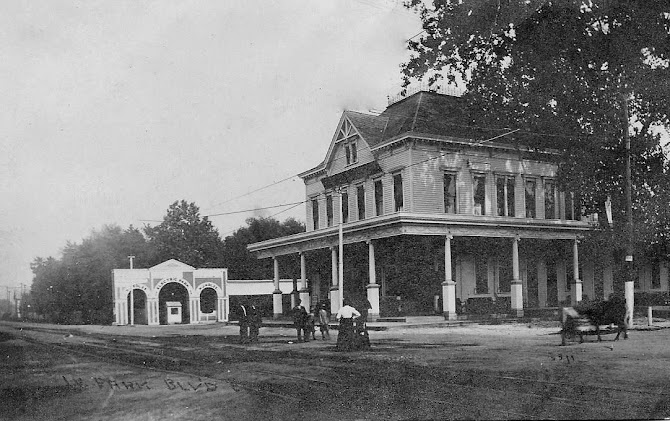

| The Cook County Insane Asylum and Infirmary at Dunning began in 1885. |

Mundelein resident Ross Goodrich, who is 81, heard a similar

expression growing up on the West Side in the 1930s and '40s. "Whenever anyone

would act a little nutsy, any of the kids, we'd say, 'Oh, gotta send them to

Dunning.' It was a pretty common expression," he says.

Hill and Goodrich are interested in the history of Dunning

because both of them had great-grandparents who died in the institution in the early 1900s.

It was never actually named Dunning.

However, the property just

south of it was owned by the Dunning family, so when the Chicago, Milwaukee

& St. Paul Railway extended a line to the area in 1882, the stop was named

Dunning Station. Then, people started calling the institution "Dunning." (In

its early years, people sometimes called it "Jefferson" since it's part of

Jefferson Township.)

When it opened in 1854, it wasn't an insane asylum. The Cook

County Infirmary was a "poor farm" and almshouse. County officials opened their

doors to people who had fallen on hard times and could not earn a living.

"They didn't provide very many services," says Joseph J.

Mehr, a Springfield clinical psychologist who wrote about Dunning in his 2002

book, "An Illustrated History of Illinois Public Mental Health Services."

"They really provided a place to sleep and food,"

he says. "And that was pretty much the extent of it."

But from the very beginning, many of the poor people who

were sent to live at the almshouse had mental illnesses. "In some ways, it's

almost similar to what we have today," Mehr says, "in that we have a lot of

people who are homeless and living on the streets, and a significant portion of

them were people who are mentally ill."

So, the county added an "Insane Department" at the almshouse.

And then, in 1870, it built a separate Cook County Insane Asylum on the

grounds.

"The feeling was it's better to isolate the population of

the mentally handicapped, the indigent, and keep them far away from the city

proper," Chicago historian Richard C. Lindberg says.

Mehr sees another motivation behind the asylum's

location: it is far from downtown Chicago. "The idea was to get people disturbed out of stress-inducing situations," he says. "Asylums were built out

in the country, and they were really pastoral, bucolic places where people

could relax."

That was the idea, anyway. In reality, Dunning was

chronically overcrowded, and patients were neglected and abused.

"You could think of this place as the prototypical evil dark

asylum of literature," Mehr says. "There wasn't much treatment. People… weren't

fed well. The food was terrible — we were evil-filled. People didn't get the kind

of medical care they ought to get. For many, many years, it was really a

terrible place."

Abuse and Corruption

In 1874, a Tribune reporter described Dunning's poorhouse as

"a shambling, helter-skelter series of wooden buildings" where dejected-looking

people with matted hair and tattered clothing were "crowded and herded together

like sheep in the shambles or hogs in the slaughtering-pens."

"The rooms swarm with vermin," an attendant told the

reporter. "The cots and bed clothing are literally alive with them. We cannot

keep the men clean and drive the parasites away unless they are

clean."

The reporter couldn't take the smell in the room,

exclaiming: "For Heaven's sake, let us get out; this stench is unbearable."

Political corruption was part of the problem at Dunning.

County officials treated it as a patronage haven, hiring pals and cronies without expertise in handling mental patients. Employees got drunk on duty,

partying and dancing late at night in the asylum. Some of the asylum's top

authorities used taxpayer money to decorate their offices and hold lavish

parties while patients were suffering in squalor.

"Everybody was a political hiree," says neighborhood historian Al Opitz. "So consequently, they had nobody to report to other

than the political boss."

In an 1889 court case, Cook County Judge Richard Prendergast

described Dunning as "a tomb for the living." He criticized the asylum for squeezing

1,000 patients into a space better suited for 500. "The presence of so many

lunatics in a room irritates all," Prendergast said. "Fighting among the

patients at night is frequent."

That same year, two attendants at the Dunning asylum were

charged with murdering patient Robert Burns. They'd kicked him in the stomach

and given him a gash on the head. A defense attorney claimed these "blows and

kicks … were beneficial to the insane man, as they were a sort of stimulus or

tonic," according to the Tribune. Jurors acquitted the attendants, blaming

Dunning's overcrowding rather than the actions of individual employees.

Even under the best of conditions, doctors didn't have many

effective treatments for people suffering from mental illness. The only drugs

they had at their disposal were sedatives. "If a person was terribly agitated,

they might dose them with chloral hydrate, which would pretty much knock them

out," Mehr says. "That's the ingredient in what used to be called a Mickey Finn

in a bar."

According to an 1886 state investigation, one of the

sedatives used at Dunning was a mixture containing chloral hydrate as well as

cannabis, hops, and potash. The investigation also found that Dunning served two kegs of beer daily; patients and employees were apparently

drinking the beer.

The same state probe harshly criticized the food Dunning

served to its inmates. A lack of fruit and fresh vegetables had caused an epidemic

of scurvy, with about 200 patients suffering from the illness. "The cooking, we

are convinced, was bad," the investigators said.

Despite all their appalling discoveries, the

investigators quoted one doctor who said, "There were some attendants who were

most excellent, who were conscientious, and endeavored to mitigate the

sufferings of the insane in every way possible." However, these employees were in

the minority and felt intimidated by Dunning's irresponsible workers.

The situation inside the Dunning poorhouse seemed somewhat

better by 1892. A journalist who visited that year didn't encounter the same

horrors others had witnessed earlier. But she reported that many of

the poorhouse residents were "too old and infirm to do anything except sit

about in joyless groups." The superintendent told her that many people ended up

in the poorhouse as a result of alcoholism. "Whisky brings the most of them,"

he said, adding, "They're foreigners mostly."

Insanity Cases in the News

In that era, Chicago newspapers often reported the stories

of local people suffering from mental illness, openly describing their symptoms

and sometimes publishing their names. In many of these stories, patients were

taken first to the Cook County Detention Hospital (at the northwest corner of

Polk and Wood streets), where judges ordered them committed at Dunning.

Here's a sample of several cases reported in 1897:

- Frank Johnson was committed to Dunning after he cut off his right hand in a fit of religious mania. "I think he will grow again," he told a judge.

- John E.N., 28, believed he was Jesus Christ.

- Timothy O'B. became "a raving maniac" after a policeman struck him in the head.

- William Mitchell, 43, an extremely emaciated African-American man, said he was hearing "the voices of spirits" and believed that people were "after him for murderous purposes."

- Theresa K., 35, was sent to Dunning after she refused to eat, declaring that her food was poisoned.

- Catherine T., 56, "was something like a wild cat." Maggie Mc., who may have fractured her skull five years earlier, was described as "silly, helpless, Irish, very poor, and 28 years of age."

- Fredericka W., 35, who was unkempt with a weather-beaten complexion, was sent to Dunning after a policeman found her sitting in a park. She said she "was searching for a prince, who had promised her marriage."

- William L., 45, was arrested when a policeman found him "wandering about the boulevards ogling women and girls." After hearing the case details, a judge declared, "Dunning." As the bailiff quickly hustled William L. toward the door, the patient turned around and shouted, "It doesn't take long to do up a man here!"

|

| Special Dunning inmate streetcars "Crazy Train" at the west end of the Irving Park line. |

|

| Unique Streetcars transported inmates from Cook County Hospital to Dunning. |

|

| Today, some of the remaining tracks from Dunning's "Crazy Train" are behind the Brickyard Target store. |

Dunning's Unmarked Graves

Throughout its early history, Dunning also included

cemeteries — not only for poorhouse residents and asylum inmates who died but

also for anyone who died in Cook County and whose family couldn't afford to pay

for a burial. Some bodies were moved to Dunning from the Chicago City Cemetery,

which was underneath what is now Lincoln Park.

Of the 300 dead from the Great Chicago Fire in 1871, 117 victims of the fire are buried on Dunning Insane Asylum property. Also buried are Civil War veterans, including Thomas Hamilton McCray, a Confederate brigadier general who moved to

Chicago after the war and died in 1891.

One of the most notorious people buried at Dunning was Johann

Hoch, a bigamist who was believed to have married 30 women and murdered at

least 10 of them. After he was hanged at Cook County Jail in 1906, other

cemeteries refused to accept his body. "In that little box that they had made

at the jail, the remains of Hoch were buried anonymously somewhere on the

grounds at Irving and Narragansett," says Lindberg, who told the story in his

2011 book "Heartland Serial Killers."

The same fate befell George Gorciak, a Hungarian immigrant

who died penniless in 1895, succumbing to typhoid. His family took his body to

Graceland Cemetery, apparently unaware that they needed to pay for a plot

there. By the end of the day, they'd hauled his coffin out to Dunning, where

burials were free in the potter's field.

The burials at Dunning included many orphans and infants —

and adults whose identities were a mystery. In 1912, an "Unknown Man" who'd

apparently stabbed himself to death was placed in the ground at Dunning.

Scandals sometimes erupted over bodies being stolen from

Dunning's cemetery by people who wanted them for anatomy demonstrations. In one

1897 case, four bodies were taken as they were being prepared for burial. Henry

Ullrich, a watchman who worked at Dunning, was convicted of selling the corpses

to Dr. William Smith, a medical professor in Missouri.

The professor claimed that the watchman had offered to kill

a "freak" and sell him the body. Smith recalled telling Ullrich, "I only want

the dead ones." Ullrich supposedly replied, "That's all right, Doc … he's in

the 'killer ward,' and they'd think he'd wandered off. They're always doing

that, you know."

County officials denied the existence of a "killer ward."

The State Takes Control

In 1910, Dunning's poorhouse residents were moved to a new

infirmary in Oak Forest. In 1912, the state took over the Dunning asylum

from Cook County, changing the official name to Chicago State Hospital.

Mehr says that conditions had already improved at Dunning over the

previous decade. One reason was the construction of smaller

buildings to house patients. And a civil service law passed in 1895 decreased the problems with patronage. Mehr says that after the state took control,

"It ended the scandals around the issue of graft and corruption." But incidents

of patients being abused still made news from time to time, he says.

Ross Goodrich says his great-grandmother, an immigrant from

Prague named Fannie Hrdlicka (pronounced Herliska), was placed in Dunning when

she became depressed after one of her children died.

|

This February 1947 photo, taken inside the Chicago State

Hospital, shows the poorly ventilated, narrow, and congested hallways where some

patients slept. (Chicago Daily News)

|

According to the family story, he says, "When the baby died,

my great-grandmother rocked the baby for a couple of days and wouldn't let it

out of her arms. And then, she was placed in Dunning because they thought she

was a little crazy. But we suspect it could have been a case of postpartum

depression. … If she was having mental difficulties of any kind, I'm not sure

that there were any other places available in those days for her to go." Hrdlicka was released from Dunning and then readmitted. She

died there in 1918.

Steven Hill says he doesn't know why his great-grandfather,

John Ohlenbusch, was living at Dunning when he died in 1910. But the death

certificate says he had dementia, so Hill suspects Ohlenbusch may have had what

later became known as Alzheimer's disease. Hill says his grandmother never

discussed her father's death at Dunning.

"People did not talk about the rough lifestyles they had and

how poor they were," Hill says. "But I do know they had a very, very tough

life."

Goodrich and Hill would like to learn more about what

happened to their ancestors at Dunning, but documents are challenging to find. The

Illinois State Archives in Springfield has Chicago State Hospital's admission

and discharge records from 1920 to 1951, but you need a court order to see

them. Some early Cook County records, showing patients sent to Dunning

between 1877 and 1887, are available for anyone to see in the state archives

branch at Northeastern Illinois University.

Changing Mental Health Treatments

In the first half of the 20th century, Chicago State

Hospital used several different treatments for mental illness. Hydrotherapy

uses hot or cold water to soothe people who are depressed or agitated. Fever

treatments induced high temperatures to kill off bacteria in the brains of

patients with syphilis.

Lobotomies were not performed at Chicago State Hospital, but

Mehr says the hospital did send some of its patients elsewhere for the

treatment, which cuts the brain's frontal lobe. "That's like shooting someone

in the head with a shotgun," he says.

For a time, some patients at Dunning and other Illinois

hospitals were given electroshock therapy "once a day, every day for years,

which is just an absolute abomination," Mehr says. "That was a terrible thing

to do."

A new era of psychiatric treatment began in 1954 with the

discovery of Thorazine, the first in a new wave of drugs that directly affected

the symptoms of mental illness.

Mehr, 71, worked for a year at Chicago State Hospital during an internship from 1964 to 1965. He says the conditions he witnessed

were vastly superior to the travesties of Dunning's early history. "My

impressions weren't all that bad," he says. And yet, he adds, "The problem…

was that these state hospitals were overcrowded."

Chicago State Hospital's buildings closed after it merged in

1970 with the nearby Charles F. Read Zone Center, which had opened on the west

side of Oak Park Avenue in 1965. Since 1970, it has been known as Chicago-Read

Mental Health Center. Today, for better or worse, fewer people with mental

illnesses stay for prolonged periods in hospitals.

Bodies Discovered in 1989

In the years after Chicago State Hospital closed, the state

sold much of the property. Today, the land includes the Dunning Square shopping

center, anchored by a Jewel store; the campus of Wright College; the

Maryville Center for Children; and houses and condominiums.

State officials apparently didn't realize that human bodies

were buried underneath a section of the Dunning land when they sold it to

Pontarelli Builders, which began work putting up houses. In 1989, a backhoe

operator working on the project found a corpse. The state had recently passed a

law requiring archaeological assessments before construction is allowed on any

property where human remains have been found, so archaeologist David Keene was

hired to examine the site. Keene was on the faculty at Loyola University then, and now he runs his own company, Archaeological Research. "The area was just littered with human remains, with human

bone all over the place, where they had disturbed things," he says.

Keene has a vivid recollection of that corpse found by the

backhoe. It appeared to be a Civil War veteran. Much of the body was still

intact, probably because it had been embalmed with arsenic, a common treatment

at the time, which would kill any organisms that would try to consume the

flesh.

"He was cut in half at the waist by the backhoe," Keene

says. "His skin was in relatively good condition … I mean, you could see his

face. But there was considerable deterioration on the face. You could see the

mustache. You could see his hair. He had red hair, but it was patchy. The other

distinguishing features of the face were no longer there. And he had a jacket

on … it was obviously a military jacket. We only saw it briefly. We didn't

spend much time with it — mostly because the odor was unbelievable, to say

the least."

Keene guided a careful excavation of the land around this

gruesome discovery — stopping the digging whenever a coffin or human remains

were revealed. He determined that a five-acre cemetery was hidden just

northwest of the current-day corner of Belle Plaine and Neenah avenues. As a

result of Keene's findings, that property was set aside as the Read-Dunning

Memorial Park, which was dedicated in 2002. Construction was allowed on the

land south of it.

This was just the second-oldest of three cemeteries on the

Dunning grounds. The earliest cemetery was near the original poorhouse, just

west of Narragansett Avenue and north of Belle Plaine. County officials had

supposedly moved the bodies out of that cemetery into the second graveyard, but

Keene says bodies did turn up there during another construction project. "We

found a little over 30 individuals there, and we were able to remove them so

(the developer) could build his building there," Keene says.

And when Wright College was under construction on the former

asylum grounds in the early 1990s, scattered human remains surfaced there, too,

Keene says.

"A femur would pop up," he says. "And it wasn't associated

with a grave of any sort. It was just mixed in with the soil from previous

construction and the removal of buildings in the past. In this area, you can walk

into any of these yards, dig in the flowerbeds, and come up with human

remains. They're part of the scattered remains from construction activity in the '20s, '30s, '40s, '50s, and '60s. Every time they built a

building, human remains would go flying."

As Keene explains, state officials constructed the hospital

buildings between 1912 and the 1960s on this land without any regard to whether

people had been buried there.

"The state came in and — as far as we can tell, from the

archaeological evidence — removed any surface evidence of burials in the entire

area," Keene says. "They actually built right on top of graves."

The third Dunning cemetery was located farther west —

underneath what is now Oak Park Avenue near Chicago-Read Mental Health Center.

While Keene was conducting his investigation in 1989, some workers walked over

and told him they'd found human remains while they were working on a broken

water main at Chicago-Read's entrance.

"So we just walked over there," Keene recalls. "And sure

enough, there were human remains everywhere. And so we began doing some

research there to figure out what the boundaries were."

Keene says it's obvious that someone must have known about

the existence of those graves when the road was put on top of them. "It's

pretty clear," he says. "When we were there — and this is just the plumbers

trying to get to the leak — they were cutting right through coffins. Somebody had to cut through some coffins to put the original

lines in."

In 1989, genealogist B. Fleig studied the records

about Dunning and documented that more than 15,000 people had been buried in

the graveyards. However, the records are incomplete, and Fleig extrapolated

that the total was closer to 38,000.

Opitz says the county's record-keeping was slipshod. "So

consequently, the number of cadavers or people that were buried here is

somewhat nebulous," he says.

The figure is unknown, but Keene says 38,000 is a

reasonable estimate. For Keene, the lesson of the Dunning graveyards is that

burial places are not as permanent as many people think they will be.

Neighborhood resident Silvija Klavins-Barshney, 50, says she

was shocked when she learned about Dunning's graveyards a few years

ago. She serves as the vice President of the church board of the Latvian

Lutheran Zion Church, located inside a building that was part of

Chicago State Hospital.

The Illinois Department of Central Management Services owns

and maintains the park.

"The more research I did, the more I felt that the story

needs to get out," she says, "because most of the people… who were buried here were forgotten in life. They were just left. Or disposed of. Or

hidden. And if that's how they lived their lives, how dare we allow them to live

their afterlife like that? How can 38,000 people be buried and then forgotten?"

Although rumors of human bones being found during earlier construction projects have circulated in the neighborhood for years, the first remains to be officially found at the Dunning site were discovered by sewer excavators on March 9, 1989. Among them was the mummified torso of a man so well preserved that he showed the handlebar mustache and mutton-chop sideburns of the 1890s. There were other remains: several baskets of bones, perhaps representing the bodies of several dozen people, according to a pathologist's report.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.