In 1888, the community was incorporated as Niles Centre, then in 1910, the spelling of Centre was Americanized to "Center."

During the real estate boom of the 1920s, large parcels of land were subdivided; many two-flat and three-flat apartment buildings were built, along with "Chicago" bungalows being the dominant architectural choice.

Large-scale development ended as a result of the Great Depression of 1929. It was not until the 1940s and into the 1950s that parents of the baby boom generation moved their families out of Chicago and into the suburbs. Skokie's housing development began again at a fever pitch. Consequently, the village developed commercially. (For example, Westfield Old Orchard was turned into Old Orchard Shopping Center.)

During the night of November 27, 1934, after a gunfight in nearby Barrington, Illinois (called the Battle of Barrington) that left two FBI agents dead, two accomplices of the notorious, 25-year-old bank-robber, "Baby Face Nelson" (Lester Gillis) dumped his bullet-riddled body in a ditch along Niles Center Road adjoining the St. Peter Catholic Cemetery, a block north of Oakton Avenue in the town.

Some of the businesses are by the intersection of Lincoln Avenue & Oakton Street in Skokie.

|

| St. Peter Catholic School and Church, Established in 1868. Postcard, circa 1880 |

|

| St. Peter Catholic Church Postcard, circa 1900 |

|

| Peter Blameuser General Merchandise [Wines, Liquors, Cigars] circa 1870 |

|

| Blameuser Building. 1895 |

|

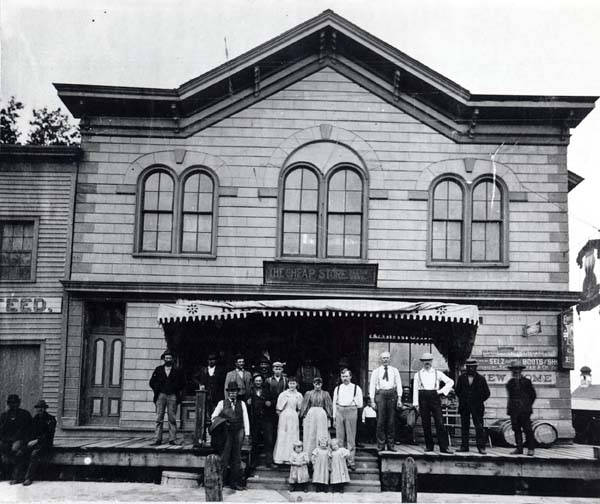

| Klehm & Sons "The Cheap Store" Building circa 1896 |

|

| Klehm Bros General Store circa 1900 |

|

| Klehm Bros General Store circa 1905 |

|

| Fred Schoening Wagon & Carriage Maker and Dry Goods Store circa 1900 {Phone: Niles Center 16-W} |

|

| Schoeneberger General Store Interior, circa 1900 |

|

| Robert Siegel Cigar Store circa 1905 |

|

| Lincoln Avenue from St-Peters Church Steeple, circa 1890 |

|

| Lincoln Avenue North of Oakton, 1890 |

|

| Niles Center Theater, circa 1916 |

|

| Lincoln Avenue North of Oakton, circa 1905 |

|

| Lincoln Avenue North of Oakton, circa 1930 |

|

| Aerial Lincoln Avenue and Oakton 1930 |

A. Kutz [Plumbing and Gas Fitting]

Alf's Hall [Dancing & Party Venue]

Bergman General Store

Charles Luebbers, Niles Center Tavern {Tel: Niles Center 84}

Freres Brothers Bakery {Tel: Niles Center 1013}

Hermann Gerhardt Horse Shoe Shop [Horseshoers & Wagon Maker]

Johanannes Schoeneberger General Store

Ludwig Luebbers [Wagon & Buggies Maker, Blacksmithing, Horseshoers]

Niles Center Bank

Niles Center Grocery & Market

Niles Center Mercantile [Studebaker Dealer, Farm Machinery, Seed] {Tel: Niles Center 26-J}

Tony Saul Tavern

Skokie Incorporated on November 15, 1940, changing its name from Niles Center.

1st National Bank of Skokie

A&P Grocery

Able Currency Exchange

Affiliated Bank

Albert’s Pizza

Alice Beauty Shop

Barney’s Place

Community Bakery

Consumers Millinery Store

Desiree Restaurant

Dieden’s Smart Shop

Florsheim Shoes

Heinz Electrical Appliance Shop {Tel: Skokie 598}

King Realtors

Krier’s Restaurant

Niles Center Coal and Building Material Co. [Lumber Mill, Building Material] {Tel: Skokie 600}

Nunn Busch

Oakton Drug

Rodell Pontiac Dealership

Schmitz Tavern

Siegal’s Cigars

Skokie Camera

Skokie Cleaners

Skokie Jewelers

Skokie Music

Skokie Paint

Urbanis Sinclair Gas Station

Village Inn Pizza

Walgreens Drug Store

|

| Oakton and Lincoln Avenue looking West circa 1948 |

|

| The intersection of Lincoln Avenue and Oakton 1946 |

|

| Lincoln Avenue North of Oakton 1957 |

|

| Oakton East from Lincoln Avenue, 1960 |

|

| Oakton West at Lincoln Avenue, circa 1960 |

|

| Lincoln Avenue at Oakton, circa 1960 |

|

| Aerial of Lincoln Avenue from St-Peter Church Steeple, circa 1965 |

|

| Aerial of Lincoln Avenue and Oakton, circa 1973 |

|

| Lincoln Avenue and Oakton 1991 |

|

| Aerial of Lincoln Avenue South from St-Peter Church Steeple 1994 |

Compiled by Neil Gale, Ph.D.