The Albright family log house and the studio was located in Hubbard Woods, 1258 Scott Avenue, Winnetka, Illinois.

|

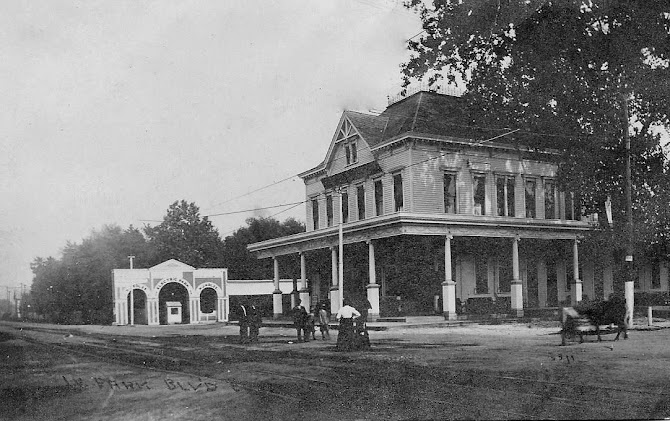

| Albright Family Log House, 1910. |

|

| Albright Family Log House, 1910. |

|

| Albright Log Studio, 1910. |

Artist Ivan Le Lorraine Albright, a painter who magnified decrepitude, whos canvases depict men and women overworn by the world. Their flesh is heavy and mottled; stubble sticks out on their chins or kneecaps. Their foreheads are furrowed and eyes encircled.

Albright combined his messages of decay and regret in several titles of his paintings, such as "The Farmer's Kitchen" and "Fleeting Time, Thou Hast Left Me Old."

|

| "The Farmer's Kitchen" by Ivan Albright. |

|

| "Fleeting Time, Thou Hast Left Me Old" by Ivan Albright. |

The darkness evident in his work seems incongruous with Albright’s background. Even within his family—his father and twin brother were artists—he stands apart.

Twins Ivan Le Lorraine and Malvin Marr were born in 1897 to Clara and Adam Emory Albright in North Harvey, Illinois. Their father, who specialized in impressionistic, sunny paintings of children, designed their log house in Hubbard Woods. The family moved into “Log Studio” in 1910. (The house was demolished in the late 1970s.)

The boys attended New Trier High School. In the 1915 yearbook, their photographs are captioned, “The Albright Twins: Two heads are better than one.”

After two years of floundering in college, the twins enlisted in the Army during World War I. Ivan worked as a medical draftsman, documenting soldiers’ wounds.

After returning to the United States the twins enrolled at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. In 1923 Malvin received a degree in sculpture and Ivan one in drawing, painting, and illustration. They both studied for another year in Philadelphia and New York.

Back in Illinois Ivan’s art soon began to move in the direction that would distinguish him. He started to use non-professional models for his portraits. He entered hundreds of juried exhibitions and won numerous awards.

In 1943 Ivan received the commission that put him briefly into the national spotlight. He was contracted by MGM to paint a picture of Dorian Gray for the movie of the same name. Albright’s macabre rendering brought him great media publicity.

A bachelor until the age of 49, Albright married Josephine Medill Patterson Reeve, a newspaper heiress, in 1946. They had four children—two from her previous marriage and two of their own. The marriage ensured Albright’s financial stability. He continued to paint and travel extensively throughout his life. He made a final etching, a self-portrait, just a few days before his death in 1983 at his home in Woodstock, Vermont.

From February to May of 2017, The Art Institute of Chicago sponsored an Ivan Albright exhibition. The retrospective displayed more than 120 of his works. It reinforced the opinion that Albright sought not to beautify but to communicate the ravages of life on body and spirit.

NOTE: Ivan Albright was the father-in-law of former U.S. Secretary of State, Madeleine Albright.

NOTE: Ivan Albright was the father-in-law of former U.S. Secretary of State, Madeleine Albright.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.