In the 1820s, the port of Baltimore was in danger. The threat came from the newly opened Erie Canal and the proposed Chesapeake and Ohio Canal construction that would parallel the Potomac River from Washington, D.C., to Cumberland, Maryland. These new water routes promised a commercial gateway to the West that would bypass Baltimore's thriving harbor and potentially hurl the city into an economic abyss. Something had to be done.

The local entrepreneurs looked across the Atlantic to England and found an answer in the newly developed railroad. In 1828, the Maryland syndicate, led by Charles Carroll ─ a signer of the Declaration of Independence ─ broke ground for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. The railroad aimed to connect Baltimore with the Ohio River and the West. Initially, the railroad's power was to be provided by horses. However, it soon became apparent that animal muscle was no match for the long distances and mountainous terrain that would have to be traveled. The solution lay with the steam engine.

By 1830, the B&O Railroad had extended its track from Baltimore to the village of Ellicott's Mills, thirteen miles to the West. The railroad was also ready to test its first steam engine, an American-made locomotive Peter Cooper of New York engineered.

It was a bright summer's day and full of promise. Syndicate members and friends piled into the open car pulled by a diminutive steam locomotive appropriately named the "Tom Thumb" with its inventor at the controls. The outbound journey took less than an hour. On the return trip, an impromptu race with a horse─drawn car developed. The locomotive came out the loser. It was an inauspicious beginning. However, within a few years, the railroad would become the dominant form of long─distance transportation and relegate the canals to the dustbin of commercial history.

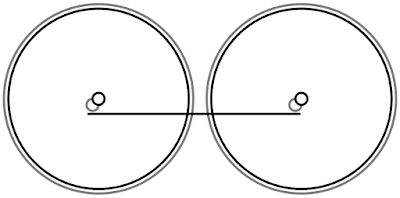

Mr. Cooper's engine boiler was smaller than today's kitchen oven in a standard size range. It was about the same diameter but at most half as high. It stood upright in the car and was filled with vertical tubes from above the furnace, which occupied the lower section. The cylinder was just 3½ inches in diameter, and the speed was achieved by gears. No natural draught could have been sufficient to keep up steam in so small a boiler, and Mr. Cooper used a blowing apparatus driven by a drum attached to one of the car wheels, over which passed a cord that in its turn worked a pulley on the shaft of the blower.

Mr. Cooper's success was such as to induce him to try a trip to Ellicott's Mills; in an open car, the first used upon the road, already mentioned, having been attached to his engine and filled with the directors and some friends, the speaker among the rest, the first journey by steam in America was commenced. The trip was most enjoyable. The curves were passed without difficulty at a speed of six miles an hour; the grades were ascended with comparative ease; the day was fine, the Company in the highest spirits, and some excited gentlemen of the party pulled out memorandum books, and when at the highest speed, which was 8 miles per hour, wrote their names and some connected sentences. The return trip from Ellicott's Mills, a distance of thirteen miles, was made in 57 minutes, averaging 6.8 miles per hour. The top speed was about 10 miles per hour.

But the triumph of this Tom Thumb engine was not altogether without a drawback. The great stage proprietors of the day were Stockton & Stokes. On this occasion, a gallant gray of incredible beauty and power was driven by them from town, attached to another car on the second track. The Company had begun making two tracks to the Mills and met the engine at the Relay House on its way back. From this point, it was determined to have a race home; the start being even, away went horse and engine, the snort of the one and the puff of the other keeping time.

At first, the gray had the best of it, for his steam would be applied to the greatest advantage on the instant, while the engine had to wait until the rotation of the wheels set the blower to work. When the engine's safety valve lifted, the horse was a quarter of a mile ahead, and its thin blue vapor showed excessive steam. The blower whistled, the smoke blew off in vapory clouds, the pace increased, the passengers shouted, the engine gained on the horse, and soon it lapped them him. The race was neck and neck, nose and nose, then the engine passed the horse, and a grand hurrah hailed the victory.

|

| The first steam engine to operate on a commercial track in the United States, the Tom Thumb became famous for its race against a horse-drawn car on August 25, 1830, from Ellicott's Mill to Baltimore. |

But it was not repeated; for just at this time, when the gray's master was about giving up, the band which drove the pulley that drove the blower slipped from the drum, the safety valve ceased to scream, and the engine for want of breath began to wheeze and pant. In vain, Mr. Cooper, his own engineman and fireman, lacerated his hands to replace the band upon the wheel. In vain, he tried to urge the fire with light wood; the horse gained on the machine and passed it, and although the band was presently replaced, and steam again did its best, the horse was too far ahead to be overtaken and came in the winner of the race."

The Tom Thumb was salvaged for parts in 1834.

"Just south of Thirty-first Street, on the lakeside, you may watch the dramatization of this century of progress in transportation, the pioneer in the field of communication. On a triple stage, in an outdoor theater, two hundred actors, seventy horses, seven trail wagons, ten trains, and the largest collection of historical vehicles ever to be used, operating under their own power, present "Wings of a Century." Here is the "Baltimore Clipper," the fastest boat of them all. From 1825 to 1850, the "Tom Thumb," the first locomotive of the B&O, the De Witt Clinton, from the old Mohawk & Hudson (New York Central), the Thomas Jefferson (1836) of the Winchester & Potomac (first railroad in Virginia) than the old "Pioneer," the Northern Pacific engine of 1851 a giant locomotive of today (the 1930s) and the 1903 Wright brothers' first airplane.

ADDITIONAL READING:

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.