The revival of the Olympic Games in 1896, unlike the original Games, had a clear, concise history. Pierre de Coubertin (1863-1937), a young French nobleman, felt that he could institute an educational program in France that approximated the ancient Greek notion of a balanced development of mind and body. The Greeks tried to revive the Olympics by holding local athletic games in Athens during the 1800s but without lasting success. It was Baron de Coubertin's determination and organizational genius. However, that gave impetus to the modern Olympic movement. In 1892 he addressed the Union des Sports Athlétiques in Paris. He persisted despite an inadequate response, and an international sports congress eventually convened on June 16, 1894. With delegates from Belgium, England, France, Greece, Italy, Russia, Spain, Sweden, and the United States in attendance, he advocated the revival of the Olympic Games. He found ready and unanimous support from the nine countries. De Coubertin had initially planned to hold the Olympic Games in France, but the representatives convinced him that Greece would host the first modern Olympics. There was no winter Olympics until 1924. The council agreed that the Summer and Winter Olympics would occur every four years in other cities worldwide.

Frank Foss, track and field:

Foss set a world record in the pole vault at the 1920 Antwerp games: 13 feet 5 inches. Foss vaulted with a bamboo pole, which was more flexible than ash and hickory poles were constructed in the 19th century. The big revolution in pole technology occurred in the 1950s when fiberglass poles enabled vaulters to fling themselves to greater and greater heights. The current world record, set last year by Sweden's Armand Duplantis, is 20 feet 3¼ inches.

Johnny Weissmuller, swimming:

Weissmuller isn't just the most famous Chicago Olympian; he may have had the most star power of any Olympian in history. As a boy, Weissmuller, an Austro-Hungarian immigrant from what is now Romania, learned to swim in Lake Michigan, then joined the Illinois Athletic Club, which had already produced several Olympians. According to club history, Weissmuller "was a high school drop-out, who probably never spent more than a year at his school, Lane Tech, and never swam on its championship swim team. He was basically a beach bum who hung out at the Fullerton Avenue beach. What early formal swimming training he picked up was at the Stanton Park Pool at the Larrabee YMCA."

The I.A.C.'s coach, William Bachrach, turned the beach bum into the greatest swimmer of the first half of the 20th century. As an amateur, Weissmuller never lost a race. He won five gold medals: in the 100-meter freestyle, 400-meter freestyle, and 4×200-meter freestyle at the 1924 Paris Games, and the 100-meter freestyle and 4×200-meter freestyle at the 1928 Amsterdam Games.

It was Weissmuller's good fortune that his swimming career ended just as the era of Hollywood's sound pictures was beginning. In 1931, he was working out at the Hollywood Athletic Club — to keep fit for his post-Olympic gig as a BVD swimsuit model — when he was approached by Cyril Hume, a scriptwriter for M.G.M.

"Hume went on to explain that the studio had assigned him to create a script for a new film, Tarzan the Ape Man," according to Michael K. Bohn's Heroes & Ballyhoo: How the Golden Age of the 1920s Transformed American Sports, by Michael K. Bohn. "He described the producer's criteria for the Tarzan role—'young, strong, well-built and reasonably attractive.' The ability to appear comfortable in a loin-cloth was also important." (Weissmuller arguably owed his shapely figure, to some extent, to a vegetarian diet picked up from John Harvey Kellogg at Kellogg's famous Michigan sanatorium.)

That was more important than the ability to act since Tarzan's dialogue was rarely more complicated than "Jane, Tarzan, Jane, Tarzan." Weissmuller described the work as "like stealing money. There was swimming in it, and I didn't have much to say. How can a guy climb trees, say 'me Tarzan, you Jane' and make a million?"

Betty Robinson, track and field:

|

| Betty Robinson, 1928 Summer Olympics, Amsterdam, Netherlands. |

One day in April 1928, Betty Robinson was late for school at Thornton Township High. She sprinted to catch a train that would take her from her home in Riverdale to Harvey. Thornton Township's track coach happened to be a passenger. Impressed with Robinson's speed, he invited her to try out for the team.

Robinson trained with the boys and beat them. Later that spring, running for the Illinois Women's Athletic Club, she tied the 100-meter world record at a track meet in Soldier Field. Then she finished second at the Olympic Trials in Newark. And so, barely three months after she'd been discovered chasing a train, 16-year-old Betty Robinson was on a ship bound for Amsterdam, where she won the gold medal in the 100 meters in the first Olympics in which women could compete in track and field in 1928.

Her next achievement was even more remarkable. In 1931, Robinson climbed into her cousin's biplane for a pleasure flight over the south suburbs. The plane crashed. According to the book Fire on the Track: Betty Robinson and the Triumph of the Early Olympic Women, rescuers saw that Robinson "had suffered at the very least a broken leg, judging by the bone poking out, [and] appeared to be dead." Robinson survived the crash, but "her chances of running again were highly improbable, given that the injured leg would likely remain shorter than the other one…. Her thighbone had fractured in numerous places, and a number of silver pins had been inserted."

Robinson wouldn't run again for two and a half years. Eventually, she regained her old speed, but there was still a barrier to resuming her track career: the pins in Robinson's leg made it impossible for her to crouch into a four-point starting position. So at the Berlin Games, she ran the third leg of the 4×100 relay, winning a gold medal after the German team dropped the baton on the final pass.

Ralph Metcalfe, track and field:

|

| Ralph Metcalfe, 1936 Summer Olympics, Berlin, Germany. The 1936 U.S. team sprinters (from left) Jesse Owens, Ralph Metcalfe, and Frank Wykoff on board the S.S. Manhattan before sailing to Germany. |

The Tilden Tech graduate was the silver medalist in the 100 meters at the 1932 Los Angeles Games and the 1936 Berlin Games, when he lost to Jesse Owens. Metcalfe did win a gold medal in Berlin as a member of the integrated 4×100-meter relay team—to the displeasure of Adolf Hitler, whose all-Aryan squad had to settle for bronze.

After the Olympics, though, Metcalfe led a much more successful life than Owens, perhaps because silver medalists aren't defined by their athletic achievements. While Owens raced horses for money and went bankrupt as a dry cleaner, Metcalfe built a career in academia and politics. He was elected alderman of the Third Ward in 1955 and succeeded William Dawson as congressman for the historically Black 1st District in 1970. On the City Council, Metcalfe was a member of the "Silent Six"—Black aldermen who faithfully followed Mayor Richard J. Daley's Machine line, in spite of Daley's lack of interest in the well-being of their South Side constituents. As a congressman, though, Metcalfe defied the mayor, refusing to support the re-election of State's Attorney Edward Hanrahan, who had ordered the raid that killed Illinois Black Panther Party Chairman Fred Hampton. ("It's never too late to be black," Metcalfe said.) Metcalfe also co-founded the Congressional Black Caucus.

Adolph Kiefer, swimming:

"I learned to swim in Lake Michigan—my father took us swimming at Wilson Avenue beach every Sunday after church," Adolph Kiefer once recalled. "I started when I was about nine or ten years old. We enjoyed it because we'd get an ice cream cone on the way home—black walnut ice cream." He soon became such a fanatic that when his family vacationed at a resort in Michigan, he swam all the way across a lake and back, a mile, each way.

Kiefer's father, a German-born candy maker, died when Kiefer was only 12, but before he passed away, he told his son that he was going to be "the best swimmer in the world."

Kiefer worked furiously to achieve the destiny his father had forecast. He swam six days a week in pools near his home in Albany Park, then on Sundays, he rode his bike, sneaked onto streetcars, or hopped onto trucks to get to the Jewish Community Center on the near south side, which had the only pool open that day. In high school, Kiefer lied about his address so he could go to Roosevelt, which had the best pool.

Although swimming historians disagree, Kiefer claimed to have invented the modern backstroke; according to an official from the International Swimming Hall of Fame, two swimmers were using a high-riding backstroke before Kiefer, but Kiefer mastered the style. "He was the king. He just had tremendous power. His strength overcame any technical flaw. His technique was not unique, but he perfected it."

At the 1936 Olympic trials, Kiefer broke the world record in the 100-meter backstroke three times. He was only a junior in high school when he sailed for the games in Berlin, but he was already recognized as one of the great swimmers of his generation, part of a U.S. swim team so talented even Hitler wanted to meet them. He showed up at a training session with filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl. "He was there with his cronies," Kiefer said. "He was a little guy with a little mustache, with a hat over his head, and three or four of us shook his hand. Actually, what I should have done is throw him in the pool! At my age, which was young, I didn't realize the atrocities or the problems which were existing then." Kiefer won the 100-meter backstroke in 1:05.9, demolishing the eight-year-old Olympic record by 2.3 seconds.

The 1940 and 1944 Olympics were canceled due to World War II, so he joined the Navy and developed a swim training program to prevent sailors from drowning. After the war, the strikingly handsome Kiefer turned down Hollywood's offer to become the next Johnny Weissmuller—as a family man, he didn't want to romance starlets onscreen—and instead founded a swimming supply company that introduced the first nylon bathing suits. It's still doing business in Bloomington.

Terry McCann, wrestling:

|

| Terry McCann, 1960 Summer Olympics, Rome, Italy. |

At Schurz High School, Terry McCann was the 1952 Illinois State Champion in the 112-pound division. McCann was an NCAA champion at 115 pounds at the University of Iowa. Then, as a 26-year-old father of five with a full-time job as a production manager for the U.S. Chamber of Commerce in Tulsa, Oklahoma, he made the Olympic team.

"No 1960 Olympian earned his place on the Big Team harder than this 5 foot 4 inch, 125-pound blond alumnus of Schurz High School," the Tribune reported in an article on McCann's return to Chicago, where his children stayed with their grandparents during the Olympics. "Last April, McCann underwent a second operation for torn knee cartilage in Tulsa, Okla., his home for the last three years. Thus, he was unable to participate in the regular Olympic tryouts a week later in Ames, Iowa. Thru unprecedented action by the American Olympic committee, he was permitted to come to the Olympic training camp in Norman and try his grip against other wrestlers of his weight. Terry finally pinned the No. 1 man, Dave Auble of Cornell university, twice."

In Rome, McCann only lost a single match on his way to winning gold in the bantamweight division, making him Illinois's only wrestling gold medalist. McCann retired from competition after the Olympics but went on to help found the U.S.A. wrestling team, the sport's governing body, served as the executive director of Toastmasters for three decades.

Bart Conner, gymnastics:

The 1984 Los Angeles Olympics were the most red-white-and-blue display of Americanism ever seen on television. That year was the peak of Reagan-era Cold War patriotism, and Bruce Springsteen's Born in the U.S.A. was the #1 album. Team U.S.A. won 83 gold medals, the most by any country in any Olympics — because the Soviets and their Eastern Bloc allies didn't show up as retaliation for our boycott of the 1980 Moscow Olympics. Two of those gold medals were won by the most all-American Olympian of all time: blond Bart Conner, who got his start on a playground in Morton Grove.

"I would play in Austin Park when I was little, and from a very early age, I was able to do a handstand on the monkey bars," Conner once told the Niles West News, his alma mater's school newspaper. "My parents realized my talent, and I just went from there."

Conner won a gold medal in the team competition and as an individual in parallel bars. In 1996, Conner won an even bigger gymnastics prize: he married Romanian gymnast Nadia Comaneci—the first gymnast to score a perfect 10.0 at the Olympics. She followed with six more en route to dominating the 1976 Games. The couple lives in Norman, Oklahoma, where Conner operates the Bart Conner Gymnastics Academy.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

A Brief History of the Modern Summer Olympic Games.

The Summer and Winter Games were traditionally held in the same year, but because of the increasing size of both Olympics, the Winter Games were shifted to a different schedule after 1992. The winter games were held in Lillehammer, Norway in 1994, Nagano, Japan in 1998, Salt Lake City, Utah, USA, in 2002, Turin, Italy in 2006, Vancouver, Canada in 2010, Sochi, Russia in 2014, Pyeongchang, South Korea in 2018, and Beijing, China in 2022.

Athens, Greece, 1896

The inaugural games of the modern Olympics were attended by as many as 280 athletes, all-male, coming from 13 countries. The athletes competed in 43 events covering nine sports; cycling, fencing, gymnastics, lawn tennis, shooting, swimming, track and field, weight lifting, and wrestling. A festive atmosphere prevailed as foreign athletes were greeted with parades and banquets. A crowd estimated at more than 60,000 attended the opening day of the competition. The 14-man U.S. team dominated the track and field events, taking first place in 9 of the 12 events.

Paris, France, 1900

The second modern Olympic competition was relegated to a sideshow of the World Exhibition, which was being held in Paris in the summer of 1900. Pierre, baron de Coubertin, founder of the modern Olympics and president of the International Olympic Committee (IOC), lost control of his hometown Games to the French government. The Games suffered from poor organization and marketing, with events conducted over a period of five months in venues that often were inadequate.

St. Louis, Missouri, U.S., 1904

As in the 1900 Olympics in Paris, the 1904 Games took a secondary role. The Games originally were scheduled for Chicago, but the location was changed to St. Louis when Olympic organizing committee officials decided to combine the Olympics with the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition, a large fair celebrating the 100th anniversary of the U.S. acquisition of the Louisiana Territory. As a result, the Games suffered. Several events became part of an "anthropological" exhibition in which American Indians, Pygmies, and other "tribal" peoples competed in events such as mud fighting and pole climbing. The Games were poorly attended by both spectators and athletes.

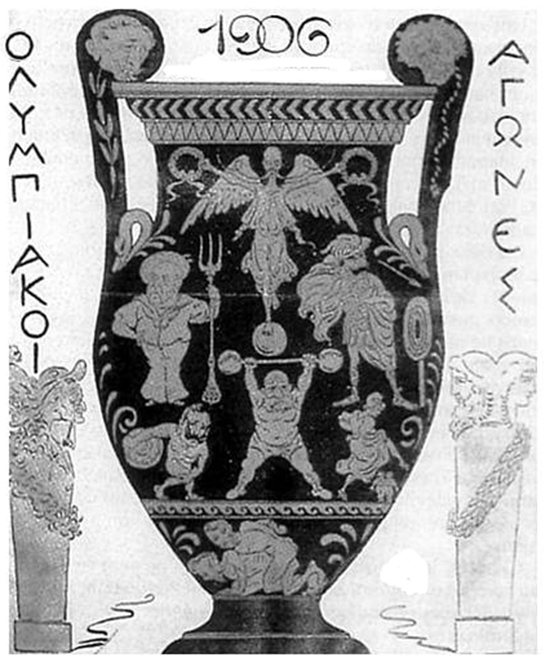

Athens, Greece, 1906

When Athens served as host of its second International Olympic Games in 1906, more events were held, and more countries participated than in the first three modern Games. With better athletes and more of them, the competition was fierce and entertaining, resulting in the most satisfying Olympics to date. As in the previous Games, Americans dominated the athletic competition, led once again by standing jumper Ray Ewry and thrower Martin Sheridan. Both had won in St. Louis and would repeat their victories in the 1908 London Olympic Games.

London, England, 1908

The 1908 Olympic Games originally were scheduled for Rome, but with Italy beset by organizational and financial obstacles, it was decided that the Games should be moved to London. The London Games were the first to be organized by the various sporting bodies concerned and the first to have an opening ceremony. The parade of athletes, like the Games, was marred by politics and controversy. The Finnish team protested Russian rule in Finland. Many Irish athletes refused to compete as subjects of the British crown and were absent from the Games. A running feud between the Americans and the British began when the American shot-putter Ralph Rose would not dip the U.S. flag in salute to King Edward VII. This refusal later became standard practice for U.S. athletes in the opening parade.

Stockholm, Sweden, 1912

Known as the "Swedish Masterpiece," the 1912 Olympics were the best organized and most efficiently run Games to that date. Electronic timing devices and a public address system were used for the first time. The Games were attended by approximately 2,400 athletes representing 28 countries. The new competition included the modern pentathlon and swimming and diving events for women. The boxing competition was canceled by the Swedish organizers, who found the sport disagreeable; this cancellation, along with controversial officiating at earlier Olympics, prompted the IOC to greatly curtail the role of local organizing groups after 1912.

Antwerp, Belgium, 1920

The 1920 Olympics were awarded to Antwerp in hopes of bringing a spirit of renewal to Belgium, which had been devastated during the war. The defeated countries of World War I—Germany, Austria, Hungary, Bulgaria, and Turkey—were not invited. The new Soviet Union chose not to attend. The city, plagued by bad weather and economic woes, had a very short time to clean up the rubble left by the war and construct new facilities for the Games. The athletics stadium was unfinished when the Games began, and athletes were housed in crowded rooms furnished with folding cots. The events were lightly attended, as few could afford tickets. In the final days, the stands were filled with schoolchildren who were given free admittance.

Paris, France, 1924

The 1924 Games represented a coming of age for the Olympics. Held in Paris in tribute to Baron de Coubertin, the retiring president of the IOC and founder of the Olympic movement, the Games featured a high caliber of competition. International federations had gained more influence over their respective sports, standardizing the rules of competition, and national Olympic organizations in most countries conducted trials to ensure that the best athletes were sent to compete. More than 3,000 athletes, including more than 100 women, represented a record 44 countries. Fencing was added to the women's events, although the total number of events decreased because of a reduction in the number of shooting and yachting competitions.

Amsterdam, Netherlands, 1928

Track-and-field and gymnastics events were added to the women's slate at the 1928 Olympics. There was much criticism of the decision, led by Baron de Coubertin and the Vatican. Women athletes, however, had formed their own track organizations and had held an Olympic-style women's competition in 1922 and 1926. Their performances at these events convinced the International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF; later International Association of Athletics Federations) that women were capable of a high level of athletic competition and deserved a place at the Olympics.

Los Angeles, California, U.S., 1932

Only about 1,300 athletes, representing 37 countries, competed in the 1932 Games. The poor participation was the result of the worldwide economic depression and the expense of traveling to California. The Los Angeles Games featured the first Olympic Village, which was located in Baldwin Hills, a suburb of Los Angeles, and covered 321 acres. The male athletes were housed in more than 500 bungalows and had access to a hospital, a library, a post office, and 40 kitchens serving a variety of cuisines. The female athletes stayed at a downtown hotel. The Los Angeles Coliseum was expanded to seat more than 100,000 people, and a new track was installed. Made of crushed peat, the new surface was exceptionally fast, resulting in 10 world records in the running events. Uniform automatic timing and the photo-finish camera were used for the first time at the 1932 Games.

Berlin, Germany, 1936

The 1936 Olympics were held in a tense, politically charged atmosphere. The Nazi Party had risen to power in 1933, two years after Berlin was awarded the Games, and its racist policies led to international debate about a boycott of the Games. Fearing a mass boycott, the IOC pressured the German government and received assurances that qualified Jewish athletes would be part of the German team and that the Games would not be used to promote Nazi ideology. Adolf Hitler's government, however, routinely failed to deliver on such promises. Only one athlete of Jewish descent was a member of the German team (see Sidebar: Helene Mayer: Fencing for the Führer); pamphlets and speeches about the natural superiority of the Aryan race were commonplace; and the Reich Sports Field, a newly constructed sports complex that covered 325 acres and included four stadiums, was draped in Nazi banners and symbols. Nonetheless, the attraction of a spirited sports competition was too great, and in the end, 49 countries chose to attend the Olympic Games in Berlin. Nearly 4,000 athletes competed in 129 events. The track-and-field competition starred American Jesse Owens, who won three individual gold medals and a fourth as a member of the triumphant U.S. 4 × 100-meter relay team. Altogether Owens and his teammates won 12 men's track-and-field gold medals; the success of Owens and the other African American athletes, referred to as "black auxiliaries" by the Nazi press, was considered a particular blow to Hitler's Aryan ideals.

The 1940 and 1944 Games

Scheduled for Helsinki, Finland (originally slated for Tokyo), and London, respectively, were canceled because of World War II.

London, England, 1948

Germany and Japan, the defeated powers, were not invited to participate. The Soviet Union also did not participate, but the Games were the first to be attended by communist countries, including Hungary, Yugoslavia, and Poland. The London Games lacked the new facilities that had been used in Los Angeles and Berlin, but the British capital's sports facilities had survived the war in good condition and were adequate for Olympic competition. Over 4,000 athletes from 59 countries participated in the Games. Poor weather and a sloppy track slowed the track-and-field competition, in which the fewest Olympic records were set in the history of the Games. The women's competition was expanded to 10 events with the addition of the 200-meter run, the long jump, and the shot put.

Helsinki, Finland, 1952

The 1952 Games were the first Olympics in which the Soviet Union participated (a Russian team had last competed in the 1912 Games), and the international tension caused by the Cold War initially prevailed. Prior to the Games, the U.S. Olympic Committee used the rivalry between East and West to raise funds for the U.S. team. The Soviet Union announced plans to house its athletes in Leningrad and fly into Helsinki each day; these plans were dropped, but a separate Olympic Village for Eastern bloc countries was created in Otaniemi. The Games themselves, however, were friendly, and by the end of the competition, Soviet officials had opened their village to all athletes. The Helsinki Games marked the return of German and Japanese teams to the Olympic competition. East Germany had applied for participation in the Games but was denied, and the German team consisted of athletes from West Germany only. Nearly 5,000 athletes competed, representing 69 countries.

Melbourne, Australia, 1956

The 1956 Olympics were the first held in the Southern Hemisphere. Because of the reversal of seasons, the Games were celebrated in November and December. The remoteness of Australia and two international crises accounted for the low number of participants; fewer than 3,500 athletes from 67 countries attended the Games. Egypt, Lebanon, and Iraq boycotted in protest of the Israeli invasion of the Sinai Peninsula in October. Moreover, a few weeks before the opening of the Games, the Soviet army entered Budapest, Hungary, and suppressed a popular uprising against the government (see also Sidebar: Hungary v. U.S.S.R.: Blood in the Water); the Netherlands, Spain, and Switzerland boycotted in protest of the Soviet invasion. East and West Germany competed as a single team, a practice that would last through the 1964 Games. Because of Australian quarantine restrictions, the equestrian events were held in Stockholm during June. The Melbourne Games introduced the practice of athletes marching into the closing ceremonies together, not segregated by nation. The track-and-field competition was held at the Melbourne Cricket Ground. The U.S. team won 15 of the 24 men's events. Sprinter Bobby Joe Morrow earned three gold medals, and Al Oerter won the first of his four consecutive gold medals in the discus.

Rome, Italy, 1960

The 1960 Olympics were the first to be fully covered by television. Taped footage of the Games was flown to New York City at the end of each day and broadcast on the CBS television network in the United States. Eurovision provided live television broadcasts throughout Europe. An Olympic Stadium, home to the opening and closing ceremonies and the track-and-field competition, and a Sports Palace were built for the Games, and several ancient sites were restored and used as venues. The Basilica of Constantine hosted the wrestling competition. The Baths of Caracalla provided the site of the gymnastic events. The marathon was run along the Appian Way and ended under the Arch of Constantine. Over 5,000 athletes representing 83 countries participated in the Rome Games.

Tokyo, Japan, 1964

The 1964 Olympics introduced improved timing and scoring technologies, including the first use of computers to keep statistics. After Taiwan and Israel were excluded from the Games of the New Emerging Forces (GANEFO), a competition that had been held in Jakarta, Indonesia, in 1963, the IOC declared that any athlete participating in that sports festival would be ineligible for the Olympics. Indonesia and North Korea then withdrew from the Tokyo Games after a number of their athletes were declared ineligible. Also absent from the 1964 Games was South Africa, which had been banned by the IOC for its racist policy of apartheid. Volleyball and judo were added. The pentathlon (later enlarged to become the heptathlon) and the 400-meter run were added to the slate of women's athletics events. More than 5,000 athletes from 93 countries competed. New Olympic records were set in 27 of the 36 events in the track-and-field competition.

Mexico City, Mexico, 1968

The 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico City were the most politically charged Olympics since the 1936 Games in Berlin. Ten days before the Games were to open, students protesting the Mexican government's use of funds for the Olympics rather than for social programs were surrounded in the Plaza of Three Cultures by the army and fired upon. More than 200 protesters were killed and over a thousand injured. At the victory ceremony for the men's 200-meter run, Americans Tommie Smith and John Carlos (gold and bronze medalists, respectively) stood barefoot, each with head bowed and a single black-gloved fist raised during the national anthem. The athletes described the gesture as a tribute to their African American heritage and a protest of the living conditions of minorities in the United States. Officials from the IOC and the U.S. Olympic Committee judged the display to be counter to the ideals of the Games; both athletes were banned from the Olympic Village and sent home. The Games were attended by 112 countries represented by almost 5,500 athletes. East and West Germany competed for the first time as separate countries. Drug testing and female gender verification were conducted for the first time. The high elevation of Mexico City (7,500 feet) was both a benefit and a hindrance to track-and-field competitors. The sprinters and field athletes thrived in the thin air. The same was not true for most of the distance runners. Dick Fosbury won the high jump with his revolutionary "Fosbury flop" technique.

Munich, West Germany, 1972

Tragedy struck the 1972 Olympics in Munich when eight Palestinian terrorists invaded the Olympic Village on September 5 and killed two members of the Israeli team. Nine other Israelis were held hostage as the terrorists bargained for the release of 200 Palestinian prisoners in Israel. All the hostages, five of their captors, and a West German policeman were slain in a failed rescue attempt. The tragedy brought the Games to a halt and cast a long shadow over what had been theretofore a memorably joyful Games. All competition was suspended for a day while a memorial service for the victims was conducted at the Olympic Stadium. IOC president Avery Brundage's decision to continue the Games after the attack was widely criticized. In subsequent Olympics, increased security measures in the Olympic Villages and competition venues protected athletes but also diminished the festive and open atmosphere that is at the heart of Olympism. More than 7,000 athletes from 122 countries participated. The swimming competition starred American Mark Spitz, who won seven gold medals (three in relays), the most by any athlete in one Olympics to that time.

Montreal, Quebec, Canada, 1976

Despite producing 32 world records and a host of memorable performances, the 1976 Games drew more attention to the apparent problems of the Olympic movement. Twenty-six countries, mostly from Africa, chose to boycott the Games when the IOC denied their request to ban New Zealand, whose national rugby team had recently toured apartheid-era South Africa. Taiwan also boycotted, when Canada, which officially recognized the People's Republic of China, would not permit Taiwan to be identified at the Games as the Republic of China. Questions arose about the integrity of the competition itself. Many athletes—particularly the East German women swimmers—were suspected of using anabolic steroids to enhance their performance. There was also concern that the amateur spirit of the Games had been undermined by the growing commercial influence on sports in the West and the pervasive government control of athletes in the Eastern bloc countries. The Montreal Games were a financial disaster, placing a burden of debt on the people of Canada and Quebec that lasted for decades. More than 6,000 athletes competed, representing 92 countries. Swimming was dominated by American men and East German women. The American men, led by John Naber (who took four gold medals), won all but one event and set 11 world records.

Moscow, U.S.S.R., 1980

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in December 1979 led to the largest boycott in the history of the Olympic movement. U.S. President Jimmy Carter took the lead in the call for a boycott of the 1980 Olympics, and approximately 60 other countries joined the United States in staying away from Moscow. A number of Western countries did not observe the boycott, notably Great Britain, France, Italy, and Sweden. In all, about 5,000 athletes representing 81 countries did attend the Games. Protests against the Soviet presence in Afghanistan continued, however. Several of the participating countries refused to attend the opening ceremony, and the Olympic hymn was played at several medal ceremonies rather than the appropriate national anthem. The Games were also hurt by rowdy behavior from spectators, cheating by officials, and security so intrusive that winners in track events were physically prevented from taking victory laps. The level of competition clearly suffered from the boycott. The Soviet team won 80 gold medals and 195 medals in all in the most lopsided final tally since the U.S. domination of the 1904 Games.

Los Angeles, California, U.S., 1984

Many communist countries, including the Soviet Union, East Germany, and Cuba, retaliated for the U.S.-led boycott of the 1980 Games by staying away from the 1984 Games, citing concerns over the safety of their athletes in what they considered a hostile and fiercely anti-communist environment. China, however, participated in the Summer Games for the first time since 1952. In all, nearly 6,800 athletes representing 140 countries came to Los Angeles. The number of events for women grew to include cycling, rhythmic gymnastics, synchronized swimming, and several new track-and-field events, most notably the marathon. Under the direction of the American entrepreneur Peter Ueberroth, the 1984 Olympics witnessed the ascension of commercialism as an integral element in the staging of the Games. Corporate sponsors, principally U.S.-based multinationals, were allowed to put Olympic symbols on their products, which were then marketed as the "official" such product of the Olympics. The Olympics turned a profit ($225 million) for the first time since 1932. Despite concerns about growing corporate involvement and the reduced competition caused by the communist boycott, the financial success and high worldwide television ratings raised optimism about the Olympic movement for the first time in a generation. As in 1980, the boycott resulted in empty lanes and canceled heats on the track, and an unbalanced distribution of medals. At the 1984 Games, the U.S. team benefited most, capturing 83 gold medals and 174 medals altogether. The track-and-field competition returned to the Memorial Coliseum, which had been renovated for the Games. American Carl Lewis won four gold medals. The U.S. women's team won 11 of the 14 swimming events.

Seoul, South Korea, 1988

Political problems threatened to return to center stage at the 1988 Games. Violent student riots took place in Seoul in the months leading up to the Games. North Korea, still technically at war with South Korea, complained bitterly that it should have cohost status. The IOC made some concessions to North Korea, but North Korea did not find them satisfactory and boycotted the games. Several other countries, notably Cuba and Ethiopia, stayed away from Seoul in solidarity with North Korea. The boycott did not have the effect of previous ones, and the Seoul Games proved to be extremely competitive. Nearly 8,500 athletes from 159 countries participated. The Olympic rule requiring participants to be amateurs was overturned in 1986, and decisions on professional participation were left to the governing bodies of particular sports. This resulted in the return of tennis, which had been dropped in 1924, to the Games. Table tennis and team archery events were also added. Canadian Ben Johnson, champion of the 100-meter run, and several weightlifters tested positive for steroid use and were disqualified. In all, 10 athletes were banned from the Games for using performance-enhancing drugs. The women's competition featured Americans Florence Griffith Joyner, winner of three gold medals, and Jackie Joyner-Kersee, who earned gold medals in the heptathlon and the long jump. The men's diving competition was again swept by Greg Louganis of the United States.

Barcelona, Spain, 1992

The 1992 Games were perhaps the most-successful modern Olympics. More than 9,300 athletes representing 169 countries participated. For the first time in three decades, there was no boycott. The dramatic political changes that had swept across eastern Europe had a tremendous effect on the Olympics. Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, and Slovenia competed as independent countries. With the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, the German team was again united. Although the truncated nation of Yugoslavia was banned, athletes from Serbia and Montenegro were allowed to compete as individuals. Athletes from the former Soviet republics competed for the last time as a team. Known as the Unified Team, its members were saluted with their individual national anthems and flags at medal ceremonies. South Africa, which had abandoned its policy of apartheid, returned to the Olympics with its first racially integrated team. The list of sports expanded to include badminton, baseball, and women's judo. The Barcelona Games were characterized by an increasing presence of professional athletes in Olympic competitions. Most conspicuous was the U.S. men's basketball team, called the "Dream Team." The team, which crushed each of its opponents to win the gold medal easily, featured 11 stars of the National Basketball Association, including Michael Jordan, Charles Barkley, Earvin ("Magic") Johnson, and Larry Bird.

Atlanta, Georgia, U.S., 1996

Selected over Athens, Greece, to host the Centennial Summer Games, Atlanta staged one of the most extravagant Games in Olympic history. With a five-hour opening ceremony and the creation of a "country fair" atmosphere complete with booths, amusement park rides, and concerts, the 1996 Olympics cost nearly $1.7 billion. For the first time, the Games received no governmental financial support. Instead, corporate sponsors—including Coca-Cola, which supplied over $300 million—and television rights were relied upon to defray costs. The result, many claimed, was excessive commercialization, and few believed that a privately funded Games would be held in the future. The Games also experienced transportation and accommodation problems, and, though extra security precautions were taken, a pipe bomb explosion in Centennial Olympic Park caused one death. The perpetrator, American Eric Rudolph, also later bombed a gay nightclub in 1997 and an abortion clinic in 1998. He was sentenced to multiple terms of life imprisonment in 2005. For the first time, all national Olympic committees (NOCs) invited to compete sent athletes, including each of the former Soviet republics, Burundi, North Korea, the Palestinian Authority, and Hong Kong, which won its first (and last) gold medal before its reunification with China (1997). A record 197 NOCs sent more than 10,000 contestants. The number of events reached 271 as women's football (soccer), beach volleyball, lightweight rowing, women's softball, and mountain biking (cross-country cycling) made their debuts. Standouts at the Atlanta Games included Carl Lewis (U.S.), who won his ninth gold medal in track and field. In women's gymnastics, the team event was won by the surprising U.S. squad.

Sydney, Australia, 2000

Sydney was narrowly chosen over Beijing as the host city of the 2000 Olympics. The IOC was attracted to the city's long history of enthusiasm for sports, its promise to use recovered toxic wastelands as sites for sporting venues, and its plan to involve the smaller countries of Oceania in hosting activities. Despite some cost overruns and a ticket scandal, the preparations and the Games themselves went smoothly. The opening ceremonies celebrated the history of Australia, especially the unique culture and contributions of the Aboriginal peoples of the continent. The high point of the opening ceremonies came when Aboriginal runner Cathy Freeman lit the Olympic flame. She later won the gold medal in the 400-metre event. The accomplishments and recognition of Freeman were an important milestone for the Australian Aboriginal peoples, who were still struggling for their place in Australian society. Nearly 11,000 athletes representing 199 IOC member countries (including 3 athletes from the United Nations dependency of East Timor) participated in the Games, which featured a record 928 medals awarded in 300 events. Several events were contested at the Olympics for the first time in 2000, including men's and women's tae kwon do, trampoline, triathlon, and synchronized diving. Other new women's events included weightlifting, modern pentathlon, and pole vault. The track-and-field competition starred American sprinter Marion Jones, who won three gold medals and two bronze.

Athens, Greece, 2004

The 2004 Olympic Games returned home to Greece, the birthplace of the ancient Games and site of the inaugural modern Olympics. The excitement surrounding the homecoming was tempered by security concerns related to Athens's proximity to the politically volatile Middle East. Moreover, serious construction delays and worries that Athens's hot, humid weather and high levels of air pollution would be detrimental to the athletes prompted the IOC to briefly consider moving the Games to another city. The media seized on these matters and predicted dismal failure. None of the expected calamities occurred. By opening day, the city had been splendidly rebuilt. All venues and facilities were ready, exceptionally modern transportation systems functioned well, and security was the best ever. The heat did affect some competitors, and spectator attendance was poor for some of the earlier events (partly as a result of negative press). More than 20 athletes were disqualified after failing tests for performance-enhancing-drug use, and controversies over scoring in gymnastics and fencing made headlines. Nevertheless, most of the 17-day event went smoothly, and the 35 competition venues were deemed excellent. The world press raved about the success of the Games as it apologized to Greece for its dire but groundless predictions. IOC president Jacques Rogge declared the Athens Olympics "unforgettable, dream Games." In 2004 a record 201 national Olympic committees were represented. Nearly 11,100 athletes competed in 37 disciplines in 28 sports; women participated in freestyle wrestling and saber fencing for the first time. American swimming phenomenon Michael Phelps topped the medals table with a record-tying eight (six gold and two bronze).

Beijing, China, 2008

In 2008 the Olympic Games were held in China for the first time. In the months prior to the Games' start, a devastating earthquake in Sichuan province, international focus on China's pollution problems, and protests over China's human rights record and Tibet became part of the Olympic story. Moreover, the Chinese government was criticized for its failure to ensure complete media freedom for visiting reporters in the lead-up to the Games. Nevertheless, China was determined to show the world, also through an Olympic lens, that it had joined the ranks of the world's most modern and influential countries, and the Games took place with few problems and were considered a great success by the IOC. The Beijing organizing committee earned high marks for the facilities that were constructed for the event, particularly the award-winning National Stadium (known as the Bird's Nest). The 2004 record for participating national Olympic committees (NOCs) was surpassed in 2008, with 204 NOCs represented in the Games. More than 11,000 athletes competed in 302 events in 28 sports, but the Beijing Games were dominated by two historic sporting feats. American swimmer Michael Phelps broke Mark Spitz's record for most gold medals won in a single Olympics, taking the gold in each of the eight events in which he competed. Phelps's eight golds brought his career total to 14, another Olympic record. While Phelps's accomplishments would likely have been the biggest story in almost any other Olympiad, sprinter Usain Bolt of Jamaica earned his share of the spotlight by claiming the mantle of "the fastest man alive" in dramatic fashion. He not only took gold in both the 100-meter and 200-meter sprints (and captured a third gold medal as a member of Jamaica's 4 × 100-meter relay team), he did so while shattering the world record time for each event.

London, England, 2012

In 2012 London became the first city to host the modern Games three times, having previously been the site of the 1908 and 1948 Olympic Games. The city was chosen as the 2012 host in a close 2005 International Olympic Committee (IOC) election, beating runner-up Paris (the heavy favorite, which also was attempting to become the first three-time host) by four votes. Safety concerns dogged the London Olympics in the weeks before the opening ceremonies, for the private firm that had been contracted to provide the Games' security notified the British government that it could not provide as many guards as it had promised (falling short by some 3,500). The government was forced to send in military personnel and local police as a stopgap measure, but the Games proceeded with no major security issues, and the episode proved to be an embarrassment rather than a crisis. The London Games' opening ceremonies proved to be one of the festival's highlights. The record for the total number of participating national Olympic committees—204—that had been established at the Beijing 2008 Olympic Games was equaled in London. The London Games featured more than 10,500 athletes who participated in 302 events in 36 sports. The most notable addition to the London program was women's boxing, which made its Olympic debut in three weight classes 112 pounds, 132 pounds, and 165 pounds. The London Games were also the first Olympiad wherein each participating country had at least one female athlete competing. The London games were dominated by two of the greatest Olympians of all time: Jamaican sprinter Usain Bolt and American swimmer Michael Phelps. By taking gold in both the 100-meter and 200-meter events, Bolt became the first man to win track's two most prestigious sprints in consecutive Olympiads. Phelps became the most decorated athlete in Olympic history by capturing six medals (including four golds) to bring his lifetime total to 22. Overall, the U.S. won an Olympics-high 46 golds, which was the country's best performance in a non-boycotted Olympics. Along with Phelps, American swimmers took home a great number of those golds, notably teenage sensation Missy Franklin (who won four golds, including both the 100-meter and 200-meter individual backstroke) and Phelps's friendly rival Ryan Lochte (winner of two golds and five total medals).

Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2016

Rio was awarded the Games by the International Olympic Committee in 2009 over bids from Chicago, Madrid, and Tokyo. The buildup to the Rio Games was beset by more problems than any other recent Olympiad. Like many 21st-century Games, particularly the 2014 Sochi Games, the Rio Olympics were plagued by massive cost overruns and construction that ran far behind schedule. Athletes, coaches, and tourists were wary of traveling to the crime-riddled city, where, in addition, an outbreak of the Zika virus led to the withdrawal of a number of prominent athletes, including golfers Rory McIlroy and Jordan Spieth. The waterways of the city were filled with debris and so polluted that the World Health Organization suggested that athletes using the open waters avoid swallowing it, cover any exposed cuts with waterproof bandages, and shower as soon as they left the site. Fewer than 50 days before the Games started, the state of Rio de Janeiro declared a "state of public calamity," which gave authorities the ability to ration essential public services and made the state eligible for federal emergency funds. Moreover, the Petrobras scandal plunged the Brazilian economy into a recession in the run-up to the Games. The Games featured a new-record 205 participating national Olympic committees, with over 11,000 athletes competing in 42 sports. Notable new sports that were added for the Rio Games were golf and rugby. The Rio Olympics also featured the debut of a Refugee Team made up of 10 athletes from various war-torn countries who had no permanent new home at the start of the Games. The Rio Olympics was highlighted by the achievements of the greatest Olympian of all time, U.S. swimmer Michael Phelps, and the greatest sprinter in Olympic history, Jamaica's Usain Bolt. After returning from a short-lived retirement, Phelps expanded his Olympic record totals for overall medals (28) and gold medals (23). On the track, Bolt won the 100-meter and 200-meter races for the third consecutive Olympic Games, becoming the first person to accomplish that feat. He also won a gold as a member of Jamaica's 4 × 100-meter relay team, which temporarily gave him three golds in three straight Olympics—before the January 2017 revelation of a failed drug test by one of his 2008 relay teammates led to the earlier relay medal's being stripped. Nevertheless, Bolt's six total individual sprint Olympic golds still solidified his claim as the fastest man in history. Americans also led the way in the women's gymnastics events as Simone Biles became the first U.S. woman—and just the fifth female ever—to capture four gymnastics golds at a single Games (all-around, floor exercise, vault, and team). Biles's fourth gold in the team event was also significant in that the American team won with the largest margin of victory (8.209 points) in that competition since the "open-ended" scoring system began in 2006.

The 2020 Summer Games

They were scheduled to be held in Tokyo, Japan, but were postponed in March 2020 in response to the coronavirus pandemic.

The 2024 Games are scheduled to be held in Paris, France.The 2028 Games are scheduled to be held in Los Angeles, California, U.S.