Ford's Athenaeum was a theatre located at 511 10th Street NW, Washington, D.C., which opened in 1861. After a fire destroyed it in 1862, he rebuilt a new building on the same site and named it Ford's Theatre, which opened in 1865.

The building is now named "Ford's Theatre National Historic Site."

|

| The Two Theatres Owned By John Thompson Ford (1829-1894). |

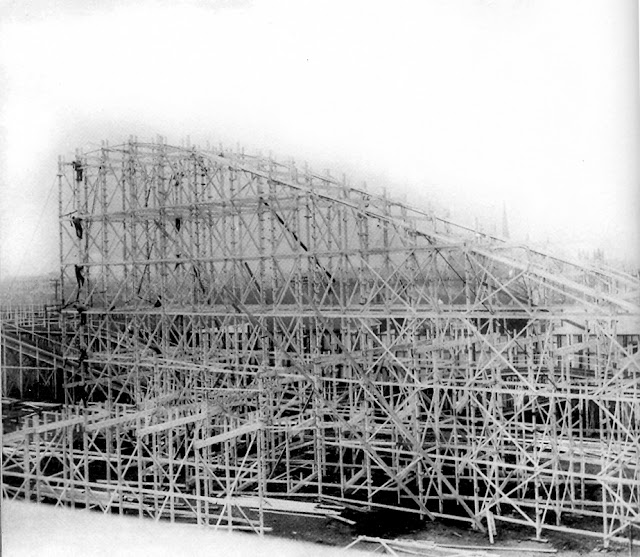

The brainchild of renowned theatre manager John T. Ford, the opera house opened its doors to the public on October 2, 1871. It was a magnificent structure, boasting a grand Italianate facade, a spacious auditorium with plush seating for 1,700, and a state-of-the-art stage equipped for elaborate productions.

|

| Ford's Opera House Stationary Header. |

The opera house quickly became a popular destination for Washingtonians, offering diverse performances, from grand operas and operettas to Shakespearean plays, vaudeville acts, and even political rallies. Notably, the famous newspaper publisher Horace Greeley was nominated as the Liberal Republican presidential candidate in 1872.

As the years passed, the opera house faced increasing competition from other theatres and entertainment venues in the city. The rise of vaudeville and musical comedy further eroded its audience for traditional operas.

By the early 20th century, the opera house was struggling financially. Attempts were made to revive its fortunes by hosting silent films and other popular attractions, but the success was short-lived.

After a final performance on April 29, 1928, the curtain fell on Ford's Opera House for the last time. The building was eventually demolished in 1930 to make way for a parking garage, sadly erasing a piece of Washington's cultural history.

While the physical structure is no more, the legacy of Ford's Opera House remains. It was a pioneering venue that brought world-class entertainment to Washington, D.C. and played a significant role in the city's cultural life. Its demise serves as a reminder of the ever-evolving nature of the arts and the importance of preserving our cultural heritage.

sidebar

John Thompson Ford worked as a bookseller in Richmond, Virginia. Ford wrote a comedy play poking fun at Richmond society. The farce was entitled "Richmond As It Is," and was produced by a minstrel company called the Nightingale Serenaders. It focused on humorous aspects of everyday life. This type of play is termed "observational comedy," which is exactly the type of humor that Jerry Seinfeld has used to established one of the most successful comedy careers of our era. He worked in management with the Nightingale Serenaders, traveling around the country. During his career, Ford managed theatres in Alexandria, Virginia; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Charleston, South Carolina; and Richmond, Virginia.Ford was the manager of this highly successful theatre at the time of the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. He was a good friend of Lincoln's assassin, John Wilkes Booth, a famous actor. Ford drew further suspicion upon himself by being in Richmond, Virginia, at the time of the assassination on April 14, 1865. Until April 2, 1865, Richmond had been the capital of the Confederate States of America and a center of anti-Lincoln conspiracies.An order was issued for Ford's arrest, and on April 18, he was arrested at his Baltimore home. His brothers, James and Harry Clay Ford, were thrown into prison along with him. John Ford complained of the effect that his incarceration would have on his business and family, and he offered to help with the investigation. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton made no reply to his two letters. After 39 days, the brothers were finally fully exonerated and set free since there was no evidence of their complicity in the crime. The government seized the theatre, and Ford was paid $88,000 ($1.7 Million today) for it by Congress.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.