Orestes "Minnie" Miñoso (born Saturnino Orestes Armas Miñoso Arrieta, November 29, 1925-March 1, 2015), in El Perico, Cuba, near Havana. Nicknamed "The Cuban Comet" and "Mr. White Sox," he was a Cuban Negro League and Major League Baseball (MLB) player. Arrieta was his mother's maiden name, while his father's name was Carlos Lopez. Both labored in the sugar cane fields outside of the big city. Minnie had two sisters and two half-brothers.

Official Stadium Names:

- White Sox Park (1910-1912)

- Comiskey Park (1913-1961, 1976-1990)

- White Sox Park (1962-1975)

- U.S. Cellular Field (1991-2016)

- Guaranteed Rate Field (2016—Present)

Minnie did not like school. During his preteen years, he quit to work in the cane fields and play ball. When his employer, the Lonja plantation, failed to field a youth team, Minnie organized one himself, finding players and equipment and managing the club. He demanded that his charges learn the signs and fined 50 centavos when they missed one. This kind of pride and determination — combined with an ability to get along with everyone — would aid Minnie immeasurably during all phases of his baseball life.

Minnie's sandlot career started near his home in El Perico, where his older half-brother Francisco Miñoso was already well known. Everyone called the younger boy Miñoso, and he did not correct them. The nickname "Minnie" came after he reached the United States — in Cuba, he was always Orestes.

Around 14, Minnie saw Martin Dihigo play, and he tried to model himself after the multitalented superstar. Minnie was a cagey opposite-field hitter whose bat was quick enough to turn on an inside pitch and scream it over the left fielder's head. Every at-bat became a game of cat and mouse.

Like his hero Dihigo, Miñoso played every position at one time or another as a teenager but was primarily a catcher. One day, he got whacked on a batter's follow-through. His mother, watching from the stands, ordered him to find a new position. He switched to pitcher and twirled a no-hitter at 18 against a junior all-star team from Central Espana. The victory was bittersweet for Miñoso, as his mother had died a month earlier.

Miñoso wandered around Cuba playing ball and doing odd jobs, using the house of a wealthy family friend, Juan Llins, as a home base. After his 20th birthday, he approached Rene Midesten, who ran the Ambrosia Candy team in Havana. Midesten asked Miñoso what position he played. The youngster explained how he could pitch and catch when he eyed the team's third baseman, who seemed to be having a tough time on the field. He quickly added third base to his résumé.

Midesten liked what he saw and hired Miñoso for $2 a game for the 1943 season, plus $8 a week working in the company garage. He hit a pinch triple in his first at-bat for the team to win a game. He earned regular action after that and finished with a .364 batting average. Miñoso moved up the semipro ladder and worked as a cigar roller and third baseman with Partagas.

Toward the end of 1945, Miñoso made it to the big time — a $150-a-month contract with Havana's Marianao club, one of the top winter league outfits in the Caribbean. His manager, Armando Marsáns, was so impressed that he quickly gave him a raise to $200 to keep him from moving on to greener pastures. Miñoso hit .300 that season and was honored as Rookie of the Year.

|

| 1945 Marianao Team Photo, "Pride of Havana" with Minnie Miñoso. |

In 1946 Miñoso signed a $300-a-month deal to play for the New York Cubans of the Negro National League. Alex Pompez, the team's owner, had been tipped off and sent Alex Carrasquel to Cuba to sign him before someone else snapped him up.

|

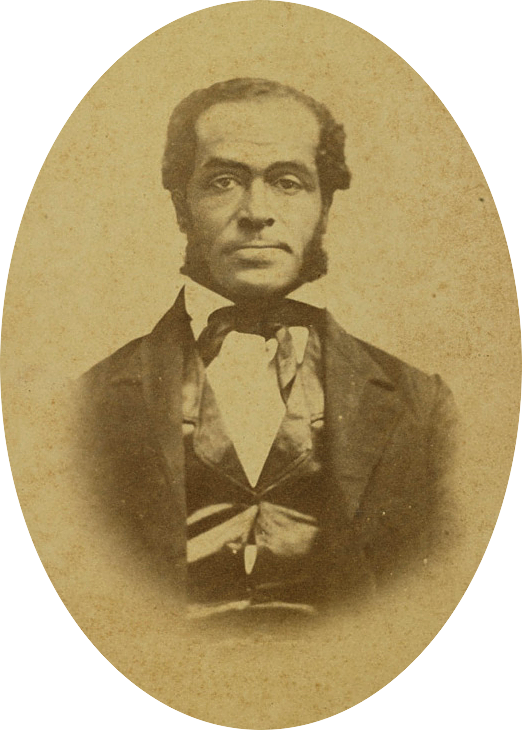

| Minnie Minoso, 1946 New York Cubans. |

There was a glut of talent in pro baseball at this time, with the significant leaguers returning from World War II as well as the Negro Leagues and Latino baseball. The Mexican League, vying to become a second major league, enticed players of all colors to jump their contracts and play south of the border. Pompez sensed that Miñoso would be a target.

Indeed, Miñoso was offered $15,000 by the Mexican League but honored his Cuban deal and remained in the United States. Besides, rumors were rampant that Mexican Leaguers might be banned from U.S. baseball. That, plus the fact that the Brooklyn Dodgers had signed Jackie Robinson, encouraged players like Miñoso to stay in the States.

Miñoso played third base for a Cubans team featuring catcher Ray Noble and pitcher Luis Tiant Sr. He appeared in 33 official games and finished 1946 with a .260 average in league play. In 1947, Miñoso became the NNL's most effective leadoff hitter, batting .294 and helping the Cubans win the pennant. He was also the East's starting third baseman in the All-Star Game. In the World Series, the Cubans beat the Cleveland Buckeyes of the Negro American League.

The man who "discovered" Miñoso for American white baseball was Abe Saperstein, of Harlem Globetrotters fame. Saperstein had a keen eye for talent, and he had good contacts through his basketball players — several of whom suited up for Negro League teams to pick up extra cash. Saperstein and old-time scout Bill Killefer went to New York to check out hurler Jose Santiago of the Cubans. They were there on behalf of Cleveland owner Bill Veeck, who had already signed Larry Doby and made him the A.L.'s first Black player.

Saperstein and Killefer found Santiago in his hotel, but all the pitcher could do was rave about his roommate, Minnie Miñoso. Miñoso had already been to a tryout with the St. Louis Cardinals, who had not offered him a contract. After watching him in action, Saperstein recommended that the Indians sign both players, and they soon did.

|

1947 Baseball Card

Orestes Minoso - Cleveland Indians |

Miñoso arrived in Dayton of the Central League for the final two weeks of the 1948 season, racked up nine extra-base hits in 11 games, and batted a sizzling .525.

Miñoso broke camp with the Indians in 1949, making his major-league debut on April 19. But he was hardly used and batted under .200 in limited action. He was sent to San Diego (Pacific Coast League) for seasoning, as Cleveland stuck with veteran Ken Keltner at the hot corner. Over the next two seasons, Miñoso crushed PCL pitching. He hit .297 with 22 homers in '49, then batted .339 in 1950, with 130 runs, 115 RBIs, and 30 stolen bases in the PCL's extended season.

Miñoso came north with the Indians out of spring training in 1951, although they had no place to play him. The third base now belonged to Al Rosen, while the outfield was manned by veterans Larry Doby, Dale Mitchell, and Bob Kennedy. Still, Miñoso had proven all he needed to against PCL pitching, so there was no point in keeping him in the minors. He saw some action at first base, spelling Luke Easter, but spent April on the bench.

On April 30, 1951, Miñoso was traded to the Chicago White Sox in a significant three-team trade that saw Gus Zernial and Dave Philley sent by Chicago to Philadelphia, Lou Brissie move from Philadephia to Cleveland, and several other players change addresses.

The Indians obviously had a win-now mentality, and Brissie addressed an immediate need. Also, the Indians had another "Negro outfielder" coming up named Harry Simpson. They felt he had more power potential than Miñoso. Finally, Greenberg had become suspicious of Miñoso's commitment when he showed up several days late for spring training. Instead of simply apologizing, Miñoso tried to sweet-talk the Cleveland brass.

|

| Chicago White Sox Logo from 1949 - 1959. |

Miñoso took the field for his new team against the New York Yankees on May 1. Comiskey Park spectators saw a black man wearing a White Sox uniform for the first time. They liked what they saw. Miñoso homered in his first at-bat, belting a Vic Raschi pitch 415 feet. The fans even forgave him after a late-inning error at third allowed New York to score the winning runs. Two weeks later, the team went on a 14-game winning streak, and Miñoso was the toast of the town. The fans even gave him his own day later that season, marking the first time the White Sox had ever feted a rookie in this manner.

Miñoso split the rest of the year between left field and third base, becoming a full-timer in the outfield after the White Sox acquired veteran Bob Dillinger from the Pittsburgh Pirates to handle the hot corner. With speedy young Jim Busby hitting .283 and swiping 26 bases, second on the club to Miñoso's league-leading 31, and shortstop Chico Carrasquel adding 14 steals, Chicago made up for the fact that it had only one power threat in its lineup, first baseman Eddie Robinson. The "Go-Go White Sox" were starting to take shape.

Miñoso slashed his way to a .326 average, second in the A.L. to Ferris Fain's .344. Miñoso's 14 triples were the most in baseball in 1951, and his 112 runs fell just two shy of the league lead. He was selected for the All-Star Game in July — his first of seven appearances. Gil McDougald edged Miñoso for Rookie of the Year honors, but fans on the South Side would not have traded their Cuban speedster for three McDougalds.

The White Sox, expected to be a .500 club in '51, won eight more games than they lost. Interestingly, at the end of the season, the April trade looked like a win-win-win for Cleveland and Chicago. Brissie gave the Indians precisely what they wanted from him. Zernial led the A.L. in homers and RBIs, and the White Sox had a top-of-the-lineup hitter to pair with emerging star Nellie Fox.

Miñoso was a revelation to Chicago fans with his relentless hustle and base-stealing ability. Whenever he reached base, the fans in Comiskey Park would chant, "Go! Go! Go!"

One of the many memorable plays he made during that season came against the Detroit Tigers. Miñoso lit out for second on a pitch by Detroit's Bill Wight, which skipped past catcher Joe Ginsberg. Miñoso never broke stride, and as he neared third, he saw Ginsberg picking up the ball and rubbing it. Miñoso kept on going and slid into a pile of three Tigers who had all converged at home plate in a panic — Wight, Ginsberg, and first baseman Walt Dropo. Ginsberg held on to the ball but missed the tag.

Miñoso infuriated enemy pitchers with his ability to "steal first." Crowding the plate, he was an expert at leaning in and getting hit by inside pitches, having learned to rotate away at the moment of impact to lessen the severity of the blow. He was plunked a league-leading 16 times in 1951 and repeated as the hit-by-pitch leader in nine of the next 10 seasons.

The 1952 White Sox continued their rise to respectability, finishing in third place with the same 81-73 record. Billy Pierce began establishing himself as the staff ace, and the bullpen performed wonderfully. The one-two punch of Miñoso and Fox helped the club squeeze 600-plus runs out of a .252 team average and just two extra-base hits per game. Miñoso led the league with 22 steals, batted .281, and had the second-highest slugging mark on the White Sox at .424. He also established himself as the team's everyday left fielder. Minnie had a few adventures out there, but his speed made up for some mistakes, and his arm was more than adequate, even in cavernous Comiskey Park.

Though not quite a baseball superstar at this point, Miñoso loved to play the part. He was difficult to miss when he hit the streets of the Windy City. He drove a green Cadillac, wore brilliantly colored silk shirts and wide-brimmed hats, sported an enormous diamond ring, and carried a roll of $100 bills in his shirt. Caddy went back and forth from Chicago to Havana for many years, with an annual stop in Florida for spring training.

In 1953, at age 28, Miñoso blossomed into one of the A.L.'s best all-around hitters. He batted .313, topped 100 in both runs and RBIs, and helped carry the White Sox offense with Nellie Fox and center fielder Jim Rivera. Billy Pierce won 18 times and led the league in strikeouts, and the bullpen came through again as Chicago racked up 89 victories. A spring winning streak by the Yankees made a run at the pennant out of the question, but the White Sox seemed to be just one power hitter away from challenging New York and Cleveland for supremacy in the A.L.

The team's new slugger turned out to be Miñoso. He crashed 19 home runs and fashioned a .535 slugging average in 1954. In fact, he reached double figures in all three extra-base categories, joining Mickey Mantle and Mickey Vernon as the only batters in the junior circuit to accomplish this feat. Miñoso finished the year with a .320 average and 119 runs scored, and the White Sox rose to 94 wins. However, a record-setting season by the Indians and a hard-luck year for Pierce kept Chicago in third place.

An episode that season in a game against the Yankees illustrates what a novelty Latino players still were in major-league baseball during the mid-1950s. Casey Stengel, always looking for an edge, ordered utility infielder Willie Miranda to curse at Miñoso, hoping to distract him in the batter's box. Miranda assumed a menacing pose and, in a harsh-sounding tone, invited him out to dinner after the game. Miñoso played along, shaking his fist at Miranda and replying in an equally menacing tone that he would be delighted. He stepped back into the box and smacked a game-winning triple.

That winter, Miñoso took a break from winter ball after a dispute with Marianao club officials. He had played for the team each offseason except 1949-50 since leaving Cuba. These campaigns often involved 70 games or more, and Miñoso probably did not mind the rest, though fans certainly missed him. He was a great favorite of Latino crowds. While he was labeled "colorful" in the United States, Miñoso was considered fairly serious and businesslike in Cuba. Cuban baseball fans would have preferred him to be more of a hot dog and probably would have liked him in an Almendares or Habana uniform. Miñoso resumed his winter baseball activities after the 1955 season, retiring from Cuban ball in 1961. He led the Winter League in batting in 1956-57.

In '55, the White Sox finally added some beef to their lineup in the person of Walt Dropo. Although Dropo did not deliver huge numbers, he anchored an excellent lineup to win 91 times and finish just five games out of first place. Marty Marion, who took over from Paul Richards in the dugout toward the end of 1954, was now the full-time skipper. He watched as Pierce returned to form with a sparkling 1.97 ERA, and Dick Donovan — picked up from the Tigers — won 15 games to give Chicago a formidable one-two pitching punch. Miñoso had a solid year, batting .288 with 10 homers and 19 stolen bases.

Chicago's quest for a first-place finish was thwarted again in 1956 by the Yankees and Indians. The White Sox dropped to 85 wins despite another year of stellar pitching. The team acquired Larry Doby over the winter, hoping he and Dropo would strike fear into the hearts of enemy hurlers. Doby did his part with excellent clutch hitting, but Dropo struggled most of the season. Minnie chipped in with 21 homers and a team-high .525 slugging average. He tied Harry Simpson, Jim Lemon, and Jackie Jensen for the league lead with 11 triples.

The 1957 White Sox finally looked as though they had solved the Yankees. Under the tutelage of new manager Al Lopez, they won early and often and stayed atop the standings for much of the first half. Pierce and Donovan led the way with All-Star seasons. At the same time, second-year shortstop Luis Aparicio teamed with the veteran two-hole hitter Fox to set the table for Doby, Rivera, Miñoso, and the first-base platoon of Dropo and Earl Torgeson. Comiskey fans watched in agony in the second half as the team began losing the close games they had won earlier in the year. The Yankees slipped past them into first place and won by four games.

After the season, Miñoso was traded away when the White Sox were offered a deal they hated to make but could not refuse. The Indians packaged Al Smith — a similar player to Miñoso, who was five years younger — and Hall of Fame hurler Early Wynn. Chicago utilityman Fred Hatfield was also part of the trade. Though just four years removed from its great '54 season, Cleveland was almost unrecognizable. Bobby Avila was the only regular left from that pennant-winning squad. The team's big slugger was now Rocky Colavito. The club had talent — including young players like Mudcat Grant, Gary Bell, Russ Nixon, Roger Maris, and Gary Geiger — but manager Bobby Bragan couldn't turn his roster into victories and was fired after 67 games. Unfortunately for the Tribe, one of the youngsters who got away that summer was Maris, who was traded to the Kansas City A's for Vic Power and Woodie Held.

The Indians improved under new skipper Joe Gordon, and Miñoso turned in his usual fine year. He led Cleveland with 168 hits, 94 runs, and 14 stolen bases and finished second on the team to Colavito with 24 homers, 80 RBIs, and 25 doubles. The Indians snuck into the first division with a late surge, ending at 77-76.

Miñoso's late-career power was a rarity in those days, but few fans were surprised. Although fleet of foot, he was perceived as a muscleman for much of his career. He tended to wear a bulky uniform and pulled his pants down well below his knees. Miñoso also walked like a big man, with his toes pointed outward. Stripped down, however, he was the same wiry 175-pounder who had broken into the big leagues a decade earlier.

The Yankees finally had an off year in 1959, and it seemed as if Miñoso was in the right place at the right time for the first time. Cleveland looked golden as the summer played out, fighting for first place with Miñoso's old team in Chicago. But the pesky White Sox would not go away, and they passed Cleveland at the end of July. When the two teams met for a four-game set in late August, the Tribe was swept and never made up the difference, losing the pennant by five games.

On paper, the Indians could have won. Colavito was the A.L. home-run champion, Held crashed 29 homers, and Miñoso chipped in with 21. Tito Francona was picked up in a winter trade and nearly won the batting title. But the White Sox got the clutch hitting and pitching a pennant-winning club needs, and the Indians did not.

After the season, Chicago owner Bill Veeck promised Miñoso a championship ring for being one of the original Go-Go Sox. Taking it a step further, he also traded to get his old friend back. And thus, on Opening Day, Miñoso was wearing his familiar White Sox uniform, and he celebrated by hitting a pair of homers. Miñoso had a good year for the defending champions, leading the AL with 184 hits and pacing the club with 105 RBIs. But the Yankees were back on their game, and the young pitchers of the Baltimore Orioles had matured, relegating the White Sox to third place with an 87-67 record.

Worse than that, a series of trades — including the one for Miñoso — gutted the White Sox of their best young players. Gone in the Miñoso trade were Norm Cash and Johnny Romano. Earl Battey and Don Mincher were also dealt for Roy Sievers. Also gone was Johnny Callison, traded to the Philadelphia Phillies for third baseman Gene Freese — who then was sent to the Reds and contributed to Cincinnati's 1961 pennant. No one took it out on Miñoso, who was still a God-like figure to Comiskey fans.

The '61 White Sox spent most of the year chasing the Tigers and Yankees. They finished with 86 wins, in fourth place. Miñoso was his usual productive and durable self, batting .280 in 152 games. His stolen-base total dipped into the single digits, but he still ran the bases aggressively, and there was plenty of pop left in his bat. Enough pop, at least, for St. Louis to roll the dice on him. With Veeck no longer in control of the White Sox, the new owners shopped Miñoso over the winter, and the Cardinals, looking for a veteran outfield mate for Curt Flood and Stan Musial, decided to give him a shot. But a broken wrist limited Minnie to just 39 games and a .196 average. His next stop was in Washington, where he served as an outfield reserve for the Senators in 1963. In the starting lineup of three power hitters, Don Lock, Jim King, and Chuck Hinton, Miñoso mostly saw action when King was benched against tough lefties. This was reflected in his .229 average.

In 1964, Miñoso returned to Chicago for his third stint with the White Sox. He served as a pinch-hitter and sometime first baseman during a thrilling pennant chase between the White Sox, Orioles, and Yankees. Chicago lost the pennant by a single game. Miñoso also logged time with Triple-A Indianapolis that season, batting .264 in 52 games.

The end was near. The wheels were gone, and Miñoso could no longer line good fastballs into the gaps. Though it was time to leave the major leagues, his status in the sport made him a big drawing card throughout the Caribbean. In 1965, he started a second career with Jalisco of the Mexican League. Now almost strictly a first baseman, he batted .360 in his first season and led the league with 106 runs and 35 doubles.

Miñoso had another big year for Jalisco in 1965, batting .348. Over the next eight seasons, he would also suit up for league clubs in Orizara, Puerto Mexico, and Torreon. In 1973, at 48, he played 120 games and hit .265 with 12 home runs and 83 RBIs. After that season, he finally called it quits.

Almost nobody noticed at the time that he had compiled more than 4,000 career hits, one of the very few professional ballplayers to do so. Researcher Scott Simkus wrote, "When you add together Minoso's Major League (1,963), minor league (429), Cuban League (838), Mexican League (715) and Negro League hits (at least 128 documented), he winds up with a career total of 4,073 professional hits."

Miñoso's retirement lasted until Bill Veeck regained control of the White Sox. In 1976, he hired Miñoso as a coach, then talked him into playing a game as a D.H. at age 50. Miñoso went hitless against the California Angels in four at-bats. One day later, he singled as a pinch-hitter. He remained with the team as a coach through 1978 and reappeared in a White Sox uniform in 1980, making two official plate appearances to join Nick Altrock as baseball's only five-decade player.

In 1993, at 68, Miñoso signed a contract with the independent Street Paul Saints. He grounded out in his only at-bat for the team. The ball and bat were sent to Cooperstown to mark the moment pro baseball had its first six-decade player. In 2003, Miñoso was at it again, pinch-hitting for the Saints. He took three pitches for balls, then let a fourth pitch go by and trotted toward the first-base bag, still hoping to "steal first." The umpire would have none of it, calling a strike; Miñoso fouled off the next pitch before letting the ball four pass and walking into the history books as a seven-decade pro. His contract, prorated for one game, paid him 32 bucks.

Miñoso was on the Baseball Writers Association of America Hall of Fame ballot for 15 years, then was dropped from the ballot after failing to be elected in the 1999 voting. His best showing was in 1988, when he got votes from 21.1 percent of the voters. He was one of 94 candidates the Committee on African-American Baseball considered in 2006 but was not enshrined.

The White Sox honored Miñoso, retiring his number (9) in 1983 and erecting a statue of him outside U.S. Cellular Field.

Miñoso died in his parked car in Chicago on March 1, 2015. He had been returning home from a friend's birthday party. The Chicago Tribune reported the cause of death as a tear in his pulmonary artery caused by "chronic obstructive pulmonary disease." Though it would appear his age was 89, given his birthdate November 29, 1925, his family and the White Sox said he was 90 at the time of his death, based on "Spanish records," the family held. Some reports had him as old as 92. He was survived by his wife of 30 years, Sharon; two sons, Orestes Jr. and Charlie; and two daughters, Marilyn and Cecilia.

President Obama said in a statement released by the White House, "For South Siders and Sox fans all across the country, including me, Minnie Miñoso is and will always be 'Mr. White Sox."

The Golden Days Era Committee made a historic decision. After a long overdue wait, Minnie Miñoso was posthumously inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame on July 24, 2022.

ACHIEVEMENTS

♦ All-Star: 1951–1954, 1957, 1959 (2 games), 1960 (2 games)

♦ Gold Glove: 1957 (Outfield), 1959 (AL-Outfield), 1960 (AL-Outfield)

♦ A.L. leader in hits (1960)

♦ A.L. leader in doubles (1957)

♦ A.L. leader in triples (1951, 1954, 1956)

♦ A.L. leader in sacrifice flies (1960, 1961)

♦ A.L. leader in stolen bases (1951–1953)

♦ A.L. leader in times on base and total bases (1954)

♦ Chicago White Sox All-Century Team (2000)

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.