|

| The Tinker Swiss Cottage in 1915. Note the sundial on the side of the driveway. |

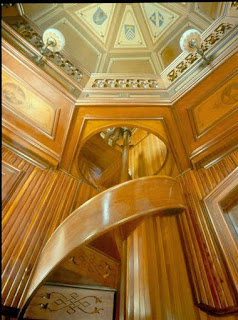

Most striking is the interior for its dimensions including the high ceilings, angled roof, and unique designs in many of the first floor rooms. Many elements of the house were created or inspired by the ideas of Tinker, including the walnut spiral staircase made by Robert out of a single piece of wood and the rooms with rounded corners. The museum contains all the original objects from the family from furniture, and artwork, to clothing and diaries.

|

| The Victorian Living Room of Tinker Swiss Cottage. In 1855, Abraham Lincoln sat in the rocking chair during a visit to the nearby South Main Street mansion of Rockford industrialist John H. Manny. |

Robert Hall Tinker (1836-1924) was born to the Rev. Reuben and Mary Throop Wood Tinker on December 31, 1836 in the Sandwich Islands (modern day Hawaii). The family settled in Westfield, New York, when Robert was 13. At the age of 15, Robert left school and began working as a bank clerk. In 1856, William Knowlton was visiting his brother in Westfield, New York, met Robert Tinker, and was impressed with him. Arriving back in Rockford, Knowlton decided to write Robert and offer him a position as clerk in the Manny Reaper Co., where he was business manager for the wealthy widow, Mrs. John H. Manny. Robert accepted the offer and arrived in Rockford on August 12th, 1856.

Knowlton and Mrs. Manny were out of the city when he arrived, so he was given a room on the second story of a small dwelling standing opposite the St. Paul freight house. When Knowlton returned he gave Robert a position as a clerk, which he held before going to work as a bookkeeper for the Emerson-Talcott Company. Later, the eastern young man, who even then was familiarly known as Bob Tinker, returned to his first employer. Knowlton and Tinker formed a partnership to sell Manny Reapers. Tinker was later placed n charge of the Manny factory.

In 1862, Robert spent 9 months traveling extensively throughout Europe. As soon as his trip was over, he began to purchase land near Mrs. Manny’s mansion and started building his cottage. On April 24, 1870, Robert Tinker and Mary Manny married and began living in his cottage in the winter and in her mansion on the north side of Kent Creek in the summer.

When he was 39 years old he served as Mayor of Rockford in 1875. Robert was instrumental in helping Rockford to acquire a Public Library and an Opera House and was prominently identified with Rockford’s business and industrial growth for 68 years.

He became President of the Rockford Oatmeal Co., Rockford Steel and Bolt Co., and of C&R and Northern R.R. until it was absorbed by the C.B.&Q line. He was head of the Water Power for many years until he resigned in 1915. Robert also served on the Rockford Park Board until he retired on February 16th, 1924.

In 1901, Mary, Robert’s wife of 31 years, passed away. He then married her niece, Jessie Dorr Hurd, in 1904. It is thought of as a marriage of convenience. In 1908, Robert became a father, at the age of 71, when Jessie adopted a son, Theodore Tinker. Robert died in the Cottage on December 31, 1924, his eighty-eighth birthday. Upon Robert Tinker's death in 1924, Jessie created a partnership with the Rockford Park District, allowing her to remain in the house until her death. After her death in 1942 the Rockford Park District acquired the property and opened the house as a museum in 1943.

Mary Dorr Manny Tinker (1829-1901) was born August 29, 1829 in Hoosick Falls, New York, the youngest of three. She was reared in her grandparents’ stately mansion and received her education at the Academy in her native city. She became interested in the manufacturing of farm implements, and it was this lively interest in and attention to her family’s occupations, public and private, that attracted her future husband’s regard to her. She maintained this interest in business through her life, and the great force of her character was intensified highly by just the culture and training she received in her early youth.

In 1852, she was married in her grandparents’ mansion to the young Reaper inventor, John H. Manny. They came to Rockford in 1853 and made their home in a small, white frame house on South Main Street. In January of 1856, John H. Manny died of tuberculosis and left Mary a widow at the age of 28. Mary was a businesswoman, staying involved with the Manny Reaper Company after John Manny’s death. She owned several parcels of land in Rockford, including the Holland House located on the north side of the creek. By 1857, Robert Tinker became her personal secretary, and on April 24, 1870 they were wed. Mary died September 4, 1901 at the age of 72.

Mary was a member of the Second Congregational Church and Women’s Missionary Society, Women’s Christian Temperance Union, Rockford’s Seminary Visiting Committee, and was a founding member of the Ladies Union Aid Society that has evolved into today’s Family Counseling Services of Northern Illinois.

Compiled by Neil Gale, Ph.D.