|

| Broadway at Leland Avenue looking north toward Lawrence Avenue Chicago, Illinois. 1926 |

Saturday, December 31, 2016

Broadway at Leland Avenue looking north toward Lawrence Avenue Chicago, Illinois. 1926

Living History of Illinois and Chicago®

Chicago,

Photograph(s) Only,

Transportation

The Story of an American Merchant, Richard W. Sears in Chicago by 1893.

Richard Warren Sears was born on December 7, 1863, in Stewartville, Minnesota, to Eliza A. Benton and James Warren Sears, a successful wagon maker.

When Richard was 15, his father lost his substantial fortune in a stock farm venture; his father died two years later. Young Richard then took a job in the general offices of the Minneapolis and St. Paul Railroad to help support his widowed mother and his sisters.

Once he had qualified as a station agent Sears asked to be transferred to a smaller town in the belief that he could do better there financially than in the big city. Eventually, he was made station agent in Redwood Falls, Minnesota, where he took advantage of every selling opportunity that came his way. He used his experience with railroad shipping and telegraph communications to develop his idea for a mail-order business.

As a railroad station agent in a small Minnesota town, Sears lived modestly, sleeping in a loft right at the station and doing chores to pay for his room and board. Since his official duties were not time-consuming, Sears soon began to look for other ways to make money after working hours. He ended up selling coal and lumber and he also shipped venison purchased from Native American tribes.

In 1886 an unexpected opportunity came his way when a jeweler in town refused to accept a shipment of watches because no rail freight charges had been paid. Rather than having the railroad pay to return the shipment, Sears obtained permission to dispose of the watches himself. He then offered them to other station agents for $14 each, pointing out that they could resell the watches for a tidy profit.

The strategy worked and before long Sears was buying more watches to sustain a flourishing business. Within just a few months after he began advertising in St. Paul, Sears quit his railroad job and set up a mail-order business in Minneapolis that he named the R. W. Sears Watch Company.

Offering goods by mail rather than in a retail store had the advantage of low operating costs. Sears had no employees and he was able to rent a small office for just $10 a month. His desk was a kitchen table and he sat on a chair he had bought for 50¢. But the shabby surroundings did not discourage the energetic young entrepreneur. Hoping to expand his market, Sears advertised his watches in national magazines and newspapers. Low costs and a growing customer base enabled him to make enough money in his first year to move to Chicago and publish a catalog of his goods.

In Chicago Sears hired Alvah C. Roebuck to fix watches that had been returned to the company for adjustments or repairs. The men soon became business partners and they started handling jewelry as well as watches. A master salesman, Sears developed a number of notable advertising and promotional schemes, including the popular and lucrative "club plan." According to the rules of the club, 38 men placed one dollar each week into a pool and chose a weekly winner by lot. Thus, at the end of 38 weeks, each man in the club had his own new watch. Such strategies boosted revenues so much that by 1889 Sears decided to sell the business for $70,000 and move to Iowa to become a banker.

Sears soon grew bored with country life, however, and before long he had started a new mail-order business featuring watches and jewelry. Because he had agreed not to compete for the same business in the Chicago market for a period of three years after selling his company, Sears established his new enterprise in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He hired Roebuck again and this time he dubbed the product of their partnership A. C. Roebuck and Company. In 1893 Sears moved the business to Chicago and renamed it Sears, Roebuck, and Company.

Once established in Chicago, the company grew rapidly. The first edition of the Sears catalog published in the mid-1880s had included a list of only 25 watches.

By 1892, however, it had expanded to 140 pages offering "everything from wagons to baby carriages, shotguns to saddles." Sales soared to nearly $280,000. A mere two years later the catalog contained 507 pages worth of merchandise that average Americans could afford. Orders poured in steadily and the customer base continued to grow. By 1900 the number of Sears catalogs in circulation reached 853,000.

Sears was the architect of numerous innovative selling strategies that contributed to his company's development. In addition to his club plan, for example, he came up with what was known as the "Iowazation" project: the company asked each of its best customers in Iowa to distribute two dozen Sears catalogs. These customers would then receive premiums based on the amount of merchandise ordered by those to whom they had distributed the catalogs. The scheme proved to be spectacularly successful and it ended up being used in other states, too.

Richard Sears had a genius for marketing and he exploited new technologies to reach customers nationwide via mail-order. At first, he targeted rural areas: People had few retail options there and they appreciated the convenience of being able to shop from their homes. Sears made use of the telegraph as well as the mails for ordering and communicating. He relied on the country's expanding rail freight system to deliver goods quickly; the passage of the Rural Free Delivery Act made servicing remote farms and villages even easier and less expensive.

Such tremendous growth led to problems, however. While Sears was a brilliant marketer (he wrote all of the catalog material), he lacked solid organizational and management skills. He frequently offered merchandise in the catalog that he did not have available for shipment, and after the orders came in he had to scramble to find the means to fill them. Workdays were frequently 16 hours long; the partners themselves toiled seven days a week. Fulfilling orders accurately and efficiently also posed a challenge. One customer wrote, "For heaven's sake, quit sending me sewing machines. Every time I go to the station I find another one.

You have shipped me five already." Roebuck became exhausted by the strain of dealing with these concerns and he sold his interest in the company to Sears in 1895 for $25,000.

With his partner out of the picture, Sears badly needed a manager. He eventually found one in Aaron Nussbaum, who bought into the company with his brother-in-law, Julius Rosenwald. It was Rosenwald, not Sears, who transformed Sears, Roebuck "from a shapeless, inefficient, rapidly expanding corporate mess into the retailing titan of much of the twentieth century." He streamlined the system by which orders were processed, employing a color-coding scheme to track them and an assembly-line method of filling them. These efficient new techniques enabled the company to meet the challenge of handling an ever-increasing number of orders.

Over the next 32 years, Sears designed 447 different housing styles, from the elaborate multistory Ivanhoe, with its elegant French doors and art glass windows, to the simpler Goldenrod, which served as a quaint, three-room and no-bath cottage for summer vacationers. (An outhouse could be purchased separately for Goldenrod and similar cottage dwellers.) Customers could choose a house to suit their individual tastes and budgets. Production ended in 1940 and Sears sold about 70,000 - 75,000 homes.

The History of Sears Modern Homes and Sears Honor Bilt Homes includes Floor Plans.

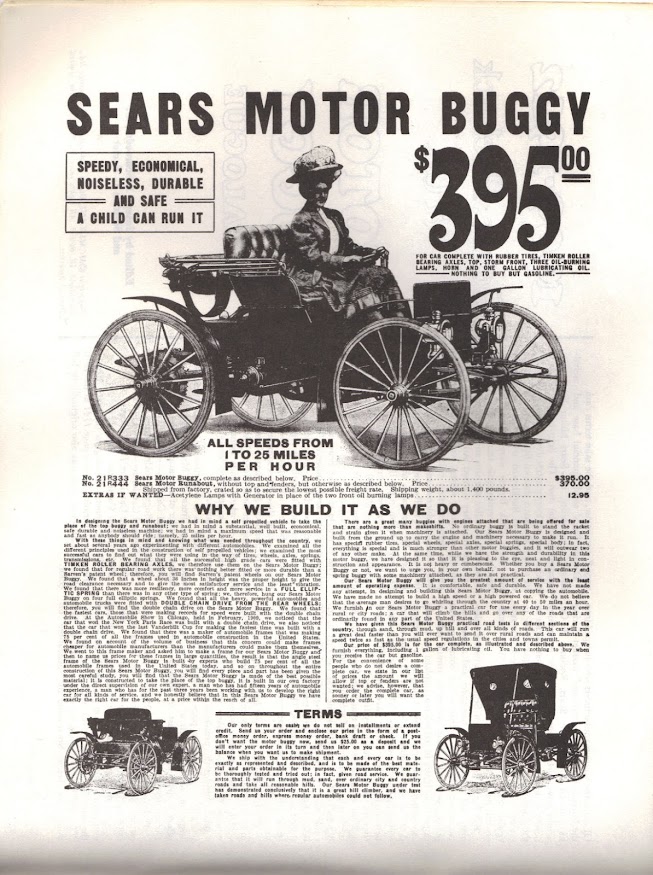

In the initial production year of 1909, the Sears Motor Buggy was offered only as a $395.00 ($12,000 in today's dollars), solid-tired, runabout. But starting in 1910, Sears offers 5 different models of the automobile. The truth of the matter is that they were all basically the same car with different amenities, like fenders, lights, tops, etc.

Richard Sears resigned as president of the company he had founded in 1909. His health was poor and many of his extravagant promotional schemes had begun to run into opposition from his fellow executives, including Rosenwald. He turned the company over to his partner and retired to his farm north of Chicago. At the time of his death on September 28, 1914, Sears left behind an estate of $25 million ($703 million today) and an enduring legacy of success in the highly competitive world of retailing.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

When Richard was 15, his father lost his substantial fortune in a stock farm venture; his father died two years later. Young Richard then took a job in the general offices of the Minneapolis and St. Paul Railroad to help support his widowed mother and his sisters.

Once he had qualified as a station agent Sears asked to be transferred to a smaller town in the belief that he could do better there financially than in the big city. Eventually, he was made station agent in Redwood Falls, Minnesota, where he took advantage of every selling opportunity that came his way. He used his experience with railroad shipping and telegraph communications to develop his idea for a mail-order business.

As a railroad station agent in a small Minnesota town, Sears lived modestly, sleeping in a loft right at the station and doing chores to pay for his room and board. Since his official duties were not time-consuming, Sears soon began to look for other ways to make money after working hours. He ended up selling coal and lumber and he also shipped venison purchased from Native American tribes.

The strategy worked and before long Sears was buying more watches to sustain a flourishing business. Within just a few months after he began advertising in St. Paul, Sears quit his railroad job and set up a mail-order business in Minneapolis that he named the R. W. Sears Watch Company.

Offering goods by mail rather than in a retail store had the advantage of low operating costs. Sears had no employees and he was able to rent a small office for just $10 a month. His desk was a kitchen table and he sat on a chair he had bought for 50¢. But the shabby surroundings did not discourage the energetic young entrepreneur. Hoping to expand his market, Sears advertised his watches in national magazines and newspapers. Low costs and a growing customer base enabled him to make enough money in his first year to move to Chicago and publish a catalog of his goods.

In Chicago Sears hired Alvah C. Roebuck to fix watches that had been returned to the company for adjustments or repairs. The men soon became business partners and they started handling jewelry as well as watches. A master salesman, Sears developed a number of notable advertising and promotional schemes, including the popular and lucrative "club plan." According to the rules of the club, 38 men placed one dollar each week into a pool and chose a weekly winner by lot. Thus, at the end of 38 weeks, each man in the club had his own new watch. Such strategies boosted revenues so much that by 1889 Sears decided to sell the business for $70,000 and move to Iowa to become a banker.

Sears soon grew bored with country life, however, and before long he had started a new mail-order business featuring watches and jewelry. Because he had agreed not to compete for the same business in the Chicago market for a period of three years after selling his company, Sears established his new enterprise in Minneapolis, Minnesota. He hired Roebuck again and this time he dubbed the product of their partnership A. C. Roebuck and Company. In 1893 Sears moved the business to Chicago and renamed it Sears, Roebuck, and Company.

Once established in Chicago, the company grew rapidly. The first edition of the Sears catalog published in the mid-1880s had included a list of only 25 watches.

By 1892, however, it had expanded to 140 pages offering "everything from wagons to baby carriages, shotguns to saddles." Sales soared to nearly $280,000. A mere two years later the catalog contained 507 pages worth of merchandise that average Americans could afford. Orders poured in steadily and the customer base continued to grow. By 1900 the number of Sears catalogs in circulation reached 853,000.

Sears was the architect of numerous innovative selling strategies that contributed to his company's development. In addition to his club plan, for example, he came up with what was known as the "Iowazation" project: the company asked each of its best customers in Iowa to distribute two dozen Sears catalogs. These customers would then receive premiums based on the amount of merchandise ordered by those to whom they had distributed the catalogs. The scheme proved to be spectacularly successful and it ended up being used in other states, too.

Richard Sears had a genius for marketing and he exploited new technologies to reach customers nationwide via mail-order. At first, he targeted rural areas: People had few retail options there and they appreciated the convenience of being able to shop from their homes. Sears made use of the telegraph as well as the mails for ordering and communicating. He relied on the country's expanding rail freight system to deliver goods quickly; the passage of the Rural Free Delivery Act made servicing remote farms and villages even easier and less expensive.

Such tremendous growth led to problems, however. While Sears was a brilliant marketer (he wrote all of the catalog material), he lacked solid organizational and management skills. He frequently offered merchandise in the catalog that he did not have available for shipment, and after the orders came in he had to scramble to find the means to fill them. Workdays were frequently 16 hours long; the partners themselves toiled seven days a week. Fulfilling orders accurately and efficiently also posed a challenge. One customer wrote, "For heaven's sake, quit sending me sewing machines. Every time I go to the station I find another one.

You have shipped me five already." Roebuck became exhausted by the strain of dealing with these concerns and he sold his interest in the company to Sears in 1895 for $25,000.

By 1895 the company was grossing almost $800,000 ($26.8 million today) a year. Five years later that figure had shot up to $11 million ($368 million today), surpassing sales at Montgomery Ward, a mail-order company that had been founded back in 1872.

In 1895 Sears married Anna Lydia Mechstroth of Minneapolis and they had three children.

In 1901 Sears and Rosenwald bought out Nussbaum for $1.25 million ($50 million today).

By 1906, for example, Sears, Roebuck was averaging 20,000 orders a day. During the Christmas season, the number jumped to 100,000 orders a day. That year the company moved into a brand-new facility with more than three million square feet of floor space. At the time it was the largest business building in the world.

Beginning in 1908 Sears, Roebuck and Co. sold mail-order Modern Homes program. Sears was not an innovative home designer. Sears was instead a very able follower of popular home designs but with the added advantage of modifying houses and hardware according to buyer tastes. Individuals could even design their own homes and submit the blueprints to Sears, which would then ship off the appropriate precut and fitted materials, putting the homeowner in full creative control. Modern Home customers had the freedom to build their own dream houses, and Sears helped realize these dreams through quality custom design and favorable financing.Over the next 32 years, Sears designed 447 different housing styles, from the elaborate multistory Ivanhoe, with its elegant French doors and art glass windows, to the simpler Goldenrod, which served as a quaint, three-room and no-bath cottage for summer vacationers. (An outhouse could be purchased separately for Goldenrod and similar cottage dwellers.) Customers could choose a house to suit their individual tastes and budgets. Production ended in 1940 and Sears sold about 70,000 - 75,000 homes.

The History of Sears Modern Homes and Sears Honor Bilt Homes includes Floor Plans.

In the initial production year of 1909, the Sears Motor Buggy was offered only as a $395.00 ($12,000 in today's dollars), solid-tired, runabout. But starting in 1910, Sears offers 5 different models of the automobile. The truth of the matter is that they were all basically the same car with different amenities, like fenders, lights, tops, etc.

Richard Sears resigned as president of the company he had founded in 1909. His health was poor and many of his extravagant promotional schemes had begun to run into opposition from his fellow executives, including Rosenwald. He turned the company over to his partner and retired to his farm north of Chicago. At the time of his death on September 28, 1914, Sears left behind an estate of $25 million ($703 million today) and an enduring legacy of success in the highly competitive world of retailing.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Living History of Illinois and Chicago®

Chicago,

Famous,

Illinois Business,

Transportation

The Oldest House in Chicago's West Ridge Community.

In 1871, Peter Schmitt Jr. (aka: Schmidt; Americanized to Smith when married to Elizabeth Phillip), built this stunning home at 6836 North Ridge Boulevard for a cost of $5,100.00. The home still stands and has been in the same family for 146 years. Today's value is 100 times the original cost at $510,000.

The number of Chicago residence jumped from 50 in 1830 to 4,170 by 1837. Construction supplies never kept up with demand. The extraordinary demand for quick shelter led to Chicago’s first reputation for architectural innovation; balloon framing. In 1833 St. Mary’s Church was built on a new principal of construction – the substitution of thin plates and studs, running the entire height of the building and held together only by nails. The older and more expensive method of construction used mortised and tenoned joints. A house now could be erected in a week, but usually was not fixed to the ground.

The Smith house was near completion but still under final construction at the time of the Great Chicago Fire. The house was much further north of the conflagulation and totally safe. There is no record of the building style, but one can assume, since it is still standing, lived in and owned by the same family, that it used “old school” construction methods.

Expense Record of Building the Schmitt House; recorded in 1871:

Carpenter Work:........Cash......$750

Mason Work:............Cash......$600

Plastering:............Cash......$250

Lumber:..........................$750

Sash and Moulding:...............$150

Lime and cement:.................$125

Locks and Things:................$75

Paint and Painters:..............$100

Brick:...........................$675

Lumber at Evanston:..............$75

Freight:.........................$50

Tinsmith:........................$63

Stone Work:......................$50

Carpenter Cash:..................$50

Moulding Door:...................$50

Other Cash payments:.............$1337

======================================

Grand Total:.....................$5150

The number of Chicago residence jumped from 50 in 1830 to 4,170 by 1837. Construction supplies never kept up with demand. The extraordinary demand for quick shelter led to Chicago’s first reputation for architectural innovation; balloon framing. In 1833 St. Mary’s Church was built on a new principal of construction – the substitution of thin plates and studs, running the entire height of the building and held together only by nails. The older and more expensive method of construction used mortised and tenoned joints. A house now could be erected in a week, but usually was not fixed to the ground.

The Smith house was near completion but still under final construction at the time of the Great Chicago Fire. The house was much further north of the conflagulation and totally safe. There is no record of the building style, but one can assume, since it is still standing, lived in and owned by the same family, that it used “old school” construction methods.

Expense Record of Building the Schmitt House; recorded in 1871:

Carpenter Work:........Cash......$750

Mason Work:............Cash......$600

Plastering:............Cash......$250

Lumber:..........................$750

Sash and Moulding:...............$150

Lime and cement:.................$125

Locks and Things:................$75

Paint and Painters:..............$100

Brick:...........................$675

Lumber at Evanston:..............$75

Freight:.........................$50

Tinsmith:........................$63

Stone Work:......................$50

Carpenter Cash:..................$50

Moulding Door:...................$50

Other Cash payments:.............$1337

======================================

Grand Total:.....................$5150

Compiled by Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Living History of Illinois and Chicago®

Chicago,

Historic Buildings

Manning & Bowes Saloon After a Bomb Explosion in 1909.

Manning & Bowes Saloon after a bomb explosion showing the room near the bar in ruins with four men standing and sitting at one end of the bar. The saloon was located at 321 State Street (today, 501 South State Street) in Chicago. (1909)

NO ARRESTS FOR BOMB NO. 30

Chicago Sunday Tribune - June 27, 1909

Although the police profess to have one man under suspicion as having caused bomb explosion No. 30 at Manning & Bowes Saloon, 321 State Street, no arrests were made yesterday (Saturday, June 26, 1909). A rumor is gaining in strength that the man under suspicion has a strong political "pull," but the police deny that this is true of the person they are seeking.

Detectives from the headquarters and the Harrison Street station house continued work throughout the day upon the case but were unable or unwilling to report any progress when asked about the bomb throwers.

Assistant Chief of Police Schuettler declares that every means the department has at its command is being used in the pursuit of the man or men responsible for the repeated outrages.

"I wish I knew who the certain police official is who knows the persona responsible for the dynamite bombs in the so-called gamblers' war; I would give ten years of my life to know who is responsible for the outrages."

This was the statement made last evening by Assistant Chief Schuettler in response to a published account said to have been made by persons who are said to be in touch with the gambling situation.

"I don't believe there is any official attached to the Chicago police department who has information that would lead to the identity of the perpetrators of the bomb outrages," said the assistant chief.

"I have officials of a powder company at work trying to locate the place where the bomb throwers obtain the powder, which is the explosive used in most of the bombs. I believe we are close to the track of the bomb throwers but cannot afford to make arrests upon suspicion. We have several persons under surveillance, but it is our business to catch them in the act in order to secure a conviction."

"It makes me feel mighty bad to know that no arrest has been made as yet, but we would be in a worse way if we made arrests upon suspicion and were unable to produce evidence against the suspects that would satisfy a court."

"We have followed up the movements of all the known gamblers and obtained lists of men that are supposed to be their enemies within the gambling fraternity. I have heard rumors that there is someone who we are afraid to arrest. That is untrue."

"If we secure evidence against anyone, no matter how he may be connected, we will not hesitate to make arrests. This last outrage has made the detectives who have worked at times upon cases determined to land the men who are responsible."

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

NO ARRESTS FOR BOMB NO. 30

Chicago Sunday Tribune - June 27, 1909

Although the police profess to have one man under suspicion as having caused bomb explosion No. 30 at Manning & Bowes Saloon, 321 State Street, no arrests were made yesterday (Saturday, June 26, 1909). A rumor is gaining in strength that the man under suspicion has a strong political "pull," but the police deny that this is true of the person they are seeking.

Detectives from the headquarters and the Harrison Street station house continued work throughout the day upon the case but were unable or unwilling to report any progress when asked about the bomb throwers.

Assistant Chief of Police Schuettler declares that every means the department has at its command is being used in the pursuit of the man or men responsible for the repeated outrages.

"I wish I knew who the certain police official is who knows the persona responsible for the dynamite bombs in the so-called gamblers' war; I would give ten years of my life to know who is responsible for the outrages."

This was the statement made last evening by Assistant Chief Schuettler in response to a published account said to have been made by persons who are said to be in touch with the gambling situation.

"I don't believe there is any official attached to the Chicago police department who has information that would lead to the identity of the perpetrators of the bomb outrages," said the assistant chief.

"I have officials of a powder company at work trying to locate the place where the bomb throwers obtain the powder, which is the explosive used in most of the bombs. I believe we are close to the track of the bomb throwers but cannot afford to make arrests upon suspicion. We have several persons under surveillance, but it is our business to catch them in the act in order to secure a conviction."

"It makes me feel mighty bad to know that no arrest has been made as yet, but we would be in a worse way if we made arrests upon suspicion and were unable to produce evidence against the suspects that would satisfy a court."

"We have followed up the movements of all the known gamblers and obtained lists of men that are supposed to be their enemies within the gambling fraternity. I have heard rumors that there is someone who we are afraid to arrest. That is untrue."

"If we secure evidence against anyone, no matter how he may be connected, we will not hesitate to make arrests. This last outrage has made the detectives who have worked at times upon cases determined to land the men who are responsible."

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Living History of Illinois and Chicago®

Chicago,

Civil Unrest,

Illinois Business,

News Story

The Hub Roller Rink & Axle Roller Rinks of Illinois.

The Hub Roller Rink opened in a desolate area in October 1950 at 4510 North Harlem Avenue, Chicago, Illinois. For those familiar with Chicago today, this area is now a shopping mall and small stores.

1950, there was nothing between the Roller Rink and Irving Park Road.

1950, there was nothing between the Roller Rink and Irving Park Road.

The "Harlem Outdoor Theater (drive-in theater)" was at the corner, and across the street was the Illinois State Police Headquarters. South of Irving Park were some small stores and restaurants that many Roller Rink regulars hung out at after the rink closed.

The "Harlem Outdoor Theater (drive-in theater)" was at the corner, and across the street was the Illinois State Police Headquarters. South of Irving Park were some small stores and restaurants that many Roller Rink regulars hung out at after the rink closed.

The HUB was a supersized roller skating rink for its time and housed a Giant Wurlitzer Pipe Organ, initially played by Leon Berry. The skating area was about 275 feet long and some 95 feet wide. The floor was much larger if you included the area outside of the rink railings that allowed skaters access to the rink floor.

The HUB was a supersized roller skating rink for its time and housed a Giant Wurlitzer Pipe Organ, initially played by Leon Berry. The skating area was about 275 feet long and some 95 feet wide. The floor was much larger if you included the area outside of the rink railings that allowed skaters access to the rink floor.

The skating had set "styles of skating" displayed on a lighted sign when the organ music would change tempos. Most of the time, the skating style was "All Skate." Some other skating styles were Couples Only, Waltz, Fox Trot, and a few fancy dances such as Collegiate and the 14-step.

The Romp was when skaters joined hands in groups of 3, 4, or 5 people, and the end person would be "whipped" around the turns, which often would end in a group falling from the high speeds.

The Romp was when skaters joined hands in groups of 3, 4, or 5 people, and the end person would be "whipped" around the turns, which often would end in a group falling from the high speeds.

The rink was open every night and had matinees on Saturday and Sunday. Weekends always found huge crowds, some who never even put on a pair of skates. The lobby area was almost as big as the rink, and it had a sizeable oval snack bar about 40 feet long in the center of the lobby. Around the outside walls were coat rooms, shoe skate rentals (leave your shoes as security for the rentals), a skate store, and a skate repair window (minor adjustments to rentals or personal skates were free), as well as a small dance floor with a jukebox.

The rink was open every night and had matinees on Saturday and Sunday. Weekends always found huge crowds, some who never even put on a pair of skates. The lobby area was almost as big as the rink, and it had a sizeable oval snack bar about 40 feet long in the center of the lobby. Around the outside walls were coat rooms, shoe skate rentals (leave your shoes as security for the rentals), a skate store, and a skate repair window (minor adjustments to rentals or personal skates were free), as well as a small dance floor with a jukebox.

A two-story office and the coat room separated the lobby from the rink. The only access to the rink area was through a large opening at the west end of the lobby.

The Hub changed owners and was renamed "The Axle" in 1974. The company, "M&R Amusement," owned all three roller skating rinks.

The Hub changed owners and was renamed "The Axle" in 1974. The company, "M&R Amusement," owned all three roller skating rinks.

People always remember Maurice Lenell when the Hub is brought up in conversations.

Maurice Lenell Cookie Co., 4510 North Harlem, Norridge, IL.

|

| Hub Roller Skating Rink Concession Stand before the Axle Remodeled. |

VIDEO

Music by Freddy Arnish, Organist at the Hub.

The skating had set "styles of skating" displayed on a lighted sign when the organ music would change tempos. Most of the time, the skating style was "All Skate." Some other skating styles were Couples Only, Waltz, Fox Trot, and a few fancy dances such as Collegiate and the 14-step.

A two-story office and the coat room separated the lobby from the rink. The only access to the rink area was through a large opening at the west end of the lobby.

People always remember Maurice Lenell when the Hub is brought up in conversations.

Maurice Lenell Cookie Co., 4510 North Harlem, Norridge, IL.

Axle Roller Rink, 4474 North Harlem Avenue, Norridge, IL.

The Axle locations were:

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

The Pro Skate Shop in the Axle Roller Rink in Niles, Illinois, in my case, gave me the first credit account I had when I was only 14 years old. I put down $60 on a great pair of professional men's roller skates, a special order. It had leather above the ankle boot, high-end wheels, hubs, trucks, and a jump bar to keep the trucks from breaking off under stress. I set the trucks so loosely that they would wobble when I lifted my foot and jiggled it. After about 6 weeks (approximately 15 skating sessions), the shoes were broken in, and I could wear thin socks without getting any blisters!

They were expensive, $175 ($630 today), but I skated there on weekends (2 or 3 times, including Sundays) for 5-6 years, so it paid off for me. Here's how it worked. Every time you went skating, you'd have to give the Pro Shop at least $5 and your shoes to store. After skating, you return the skates to the Pro Shop and provide them with the roller skates to keep until you return the next time. I never told my parents until the day I paid them off (in a little over a year) and brought them home.

During the Intermissions, the rink held age-related speed races. I won a lot! The winners would get a free pass for their following admission.

The Axle locations were:

- Countryside, IL: Route 66, just East of LaGrange Road. (Closed Mid-1978)

- Norridge, IL 4510 North Harlem. [Formerly: Hub Roller Skating Rink, Chicago]

- Niles, IL: Milwaukee Avenue just north of Golf Road (Closed August 8, 1984)

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Living History of Illinois and Chicago®

Chicago,

Entertainment,

Films - Movies - Videos,

IL Northeast,

Postcard(s),

Sports

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)