|

| Chicago's Bob Bell |

His school friends nicknamed him "Pinto" after his spotted horse named "Pinto" because of his freckled face. The name stuck for his entire life.

Pinot was known for a children's storytelling record album and an illustrated read-along book set in 1946. He became popular in the late 1940s and was the mascot for Capitol Records.

|

| Three Clowns: Abbott and Costello with Pinto Colvig as Bozo the Clown. |

|

| Bozo the Clown gets the bird from a bird to the enjoyment of the kids in the audience. Pinto Colvig plays the Clown on KTTV's Bozo Circus. (c.1949) |

Before Willard Scott joined NBC's "Today" show as its weatherman in 1980, his long career included playing Bozo the Clown on children's television.

|

| The Jackson 5 and sister Janet on Bozo's Circus |

Bozo was created as a character by Livingston, who produced a children's storytelling record album and illustrative read-along book set, the first of its kind, titled Bozo at the Circus for Capitol Records and released in October 1946. Colvig portrayed the character on this and subsequent Bozo read-along records. The albums were trendy, and the character became a mascot for the record company and was later nicknamed "Bozo the Capitol Clown."

This is a promotional film made by Capitol Records to promote records starring "Bozo The Capitol Clown," the character created by Alan W. Livingston. This film would be sent to record and department stores in the early 1950s and played before the appearance of Bozo at live venues.

Many non-Bozo Capitol children's records had a "Bozo Approved" label on the record jacket. In 1948, Capitol and Livingston began setting up royalty arrangements with manufacturers and television stations to use the Bozo character. KTTV in Los Angeles began broadcasting the first show, Bozo's Circus, in 1949, featuring Colvig as Bozo with his blue-and-red costume, big red hair, and whiteface clown makeup on Fridays at 7:30 PM.

In 1956, Larry Harmon, one of several actors hired by Livingston and Capitol Records to portray Bozo at promotional appearances, formed a business partnership and bought the licensing rights (excluding the record-readers) to the character when Livingston briefly left Capitol in 1956. Harmon renamed the character "Bozo, The World's Most Famous Clown" and modified the voice, laugh and costume. He then worked with a wig stylist to get the wing-tipped bright orange style and look of the hair that had previously appeared in Capitol's Bozo comic books. He started his own animation studio and distributed (through Jayark Films Corporation) a series of cartoons (with Harmon as the voice of Bozo) to television stations, along with the rights for each to hire its own live Bozo host, beginning with KTLA-TV in Los Angeles on January 5, 1959, and starring Vance Colvig, Jr., son of the original "Bozo the Clown," Pinto Colvig.

Unlike many other shows on television, "Bozo the Clown" was mostly a franchise as opposed to being syndicated, meaning that local TV stations could put on their own local productions of the show complete with their own Bozo. At its zenith, Harmon's franchise employed more than 200 Bozos, and 183 television stations around the country carried the syndicated television show "Bozo the Clown."

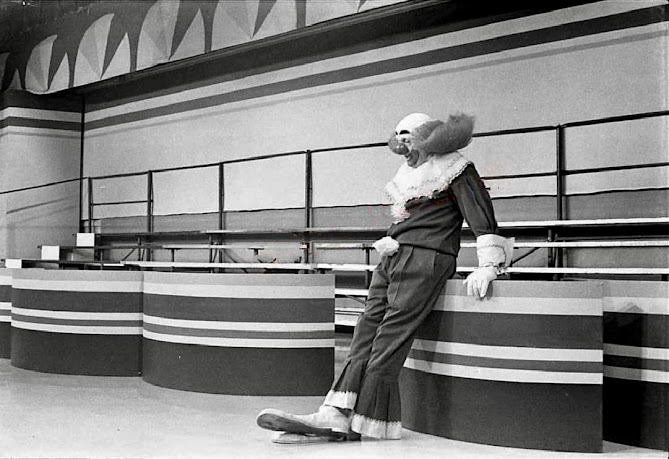

Another successful show that used this model was the fellow children's program Romper Room. Because each market used a different portrayer for the character, the voice and look of each market's Bozo also differed slightly. One example is the voice and laugh of Chicago's WGN-TV Bob Bell, who wore a red costume throughout the first decade of his portrayal.

The wigs for Bozo were originally manufactured through the Hollywood firm Emil Corsillo Inc. The company designed and manufactured toupees and wigs for the entertainment industry. Bozo's headpiece was made from yak hair, which was adhered to a canvas base with a starched burlap interior foundation. The hair was styled and formed, then sprayed with a heavy coat of lacquer to keep its form. From time to time, the headpiece needed freshening and was sent to the Hollywood factory for quick refurbishing. The canvas top would slide over the actor's forehead. Except for the Bozo wigs for WGN-TV Chicago, the eyebrows were permanently painted on the headpiece.

In 1965, Harmon bought out his business partners and became the sole owner of the licensing rights. Thinking that one national show that he wholly owned would be more profitable for his company, Harmon produced 130 of his own half-hour shows from 1965 to 1967 titled Bozo's Big Top, which aired on Boston's WHDH-TV (now WCVB-TV) with Boston's Bozo, Frank Avruch, for syndication in 1966.

Boston's WHDH-TV Channel 5 produced a local weekday version of the Bozo show between 1959 and 1970, and Frank Avruch played the title role. These excerpts are from a 1966 broadcast.

Avruch's portrayal and look of Bozo resembled Harmon's more so than most of the other portrayers at the time. Avruch was enlisted by UNICEF as an international ambassador and was featured in a documentary, Bozo's Adventures in Asia.The show's distribution network included New York City, Los Angeles, Washington, DC, and Boston at one point, though most television stations still preferred to continue producing their own versions.

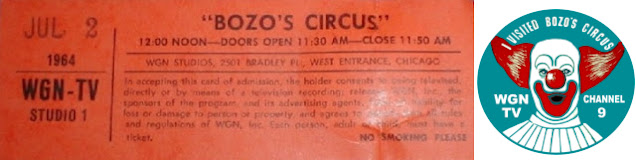

The most popular local version was Bob Bell and WGN-TV Chicago's Bozo's Circus, which went national via cable and satellite in 1978 and had a waiting list for studio audience reservations that eventually reached ten years.

Bozo's Circus is On The Air!

LOCAL WGN-TV CHICAGO HISTORY

Other titles were: Bozo, Bozo's Circus, and The Bozo Super Sunday Show.

WGN-TV's first incarnation of the show was a live half-hour cartoon showcase titled Bozo, hosted by character actor and staff announcer Bob Bell in the title role performing comedy bits between cartoons, weekdays at noon for six-and-a-half months beginning June 20, 1960. After a short hiatus to facilitate WGN-TV's move from Tribune Tower in downtown Chicago to the city's northwest side, the show was relaunched in an expanded one-hour format as Bozo's Circus, which premiered at noon on September 11, 1961. The live show featured Bell as Bozo (although he did not perform on the first telecast), host Ned Locke as "Ringmaster Ned," a 13-piece orchestra, comedy sketches, circus acts, cartoons, games, and prizes before a 200+ studio audience.

|

| 1963 Photo postcard of Oliver O. Oliver (Ray Rayner), Bozo the Clown (Bob Bell), Sandy the Clown (Don Sandburg), and Ringmaster Ned (Ned Locke) on WGN-TV Bozo's Circus |

Rayner was hosting WGN-TV's Dick Tracy Show (which also premiered the same day as Bozo's Circus) and later replaced Dick Coughlan as host of Breakfast with Bugs Bunny, retitled Ray Rayner and His Friends. WGN musical director Bob Trendler led the WGN Orchestra, dubbed the "Big Top Band."

|

| Ray Rayner was the first. NATIONAL "SPEAKING" TV Ronald McDonald. 1968-69. |

SIDEBAR

Ronald McDonald - Immediately following Willard Scott's three-year-run as WRC-TV Washington, D.C.'s Bozo, the show's sponsors, McDonald's drive-in restaurant franchisees John Gibson and Oscar Goldstein (Gee Gee Distributing Corporation), hired Scott to portray "Ronald McDonald, the Hamburger-Happy Clown" for their local commercials on the character's first three television 'spots.' McDonald's replaced Scott with other actors for their national commercials, and the character's costume was changed.One of them was Ray Rayner (Oliver O. Oliver on WGN-TV's Bozo's Circus), who appeared in McDonald's national ads in 1968. In the mid-1960s, Andy Amyx, performing as Bozo on Jacksonville, Florida, television station WFGA, was hired to periodically do local appearances of Ronald McDonald. Andy recalls having to return the wardrobe to the agency after each performance.

sidebar

The Magic Arrows were replaced by the Bozoputer, a random number generator.

|

| Magician Marshall Brodien demonstrates magic tricks at the upstairs Baer's Treasure Chest's Professional Magic Shop. |

From 1960 until 1970, Bozo appeared in a red costume. Larry Harmon, the owner of Bozo's character license, insisted Bozo wear a blue costume. Harmon did not have his way regarding the costume's color in Chicago until Don Sandburg, "Bozo's Circus" producer, writer and 'Sandy the Tramp' from 1961 to 1969, moved to California.

A primetime version titled 'Big Top' was seen from September through January on Wednesday nights in 1965 through 1967.

Ray Rayner left Bozo's Circus in 1971 and was briefly replaced by actor Pat Tobin as Oliver's cousin "Elrod T. Potter" and then by magician John Thompson (an acquaintance of Roy Brown's and Marshall Brodien's) as "Clod Hopper." (Tobin previously had played Bozo on KSOO-TV in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, and Thompson has appeared on A&E's Criss Angel Mindfreak.) Rayner periodically returned to guest-host in his morning show's jumpsuit as "Mr. Ray" when Ned Locke was absent. The show had its 500,000th visitor in the same year.

|

| Left to Right; Clod Hopper (1972-1973), Cooky (1968–1994), Ray Rayner (Oliver O. Oliver 1961–1971), and Bozo. Ray Rayner was still helping out Bozo's Circus after his character ended in 1972. |

By 1973, WGN gave up on Thompson and increased Brodien's appearances as Wizzo. That same year, the National Association of Broadcasters issued an edict forbidding the practice of children's TV show hosts doubling as pitchmen for products. This resulted in significant cutbacks to children's show production budgets.

In 1975, Bob Trendler retired from television, and his Big Top Band was reduced to a three-piece band led by Tom Fitzsimmons. Locke also retired from television in 1976 and was replaced by Frazier Thomas, host of WGN's Family Classics and Garfield Goose and Friends. At that point, Garfield Goose and Friends ended its 24-year run on Chicago television with the puppets moving to a segment on Bozo's Circus. As the storyline went, Gar "bought" Bozo's Circus from the retiring Ringmaster Ned and appointed "Prime Minister" Thomas as the new Circus Manager. In 1978, when WGN-TV became a national superstation on cable and satellite through what is now WGN America, the show gained more of a national following.

In 1979, Bozo's Circus added "TV Powww!" where those at home could play a video game by phone. How did this work?[1]

By 1980, Chicago's public schools stopped allowing students to go home for lunch, and Ray Rayner announced his imminent retirement from his morning show and Chicago television. The show stopped issuing tickets; the wait to be part of the audience was eight years long.

The following year, beginning a summer hiatus and airing taped shows pushed the ticket wait time back to ten years. On August 11, 1980, Bozo's Circus was renamed "The Bozo Show" and moved to weekdays at 8:00 AM, on tape, immediately following Ray Rayner and His Friends. On January 26, 1981, The Bozo Show replaced Ray Rayner and His Friends at 7:00 AM. The program expanded to 90 minutes, the circus acts and Garfield Goose and Friends puppets were dropped, and Cuddly Dudley (a puppet on Ray Rayner and His Friends voiced and operated by Roy Brown) and more cartoons were added. In 1983, Pat Hurley from ABC-TV's "Kids Are People Too" joined the cast as himself, interviewing kids in the studio audience and periodically participating in sketches.

On May 1, 1984, Larry Harmon, as Bozo the Clown, announced his write-in candidacy for President of the United States. That afternoon, dressed as Bozo, he arrived at Columbia University in a 1977 Cadillac limousine accompanied by "secret service" men wearing suits, sunglasses, and red clown noses.

The college punk band "Nasty Bozos '84" hosted the event and performed during the announcement. Earlier that day, Bozo creator Larry Harmon appeared on the Today Show, explaining that he went into children's television to become a "doctor of humor, love, peace, and understanding in this world." He further described his decision to run for President, against Ronald Reagan (R) and Walter Mondale (D), as a response to media calls to "put the real Bozo in the White House." It was reported that two assassination attempts were made on Bozo's life, but maybe just comedy. Harmon was never at a loss for ideas regarding promoting Bozo. Arizona was the only state to report the number of votes for Bozo, which turned out to be only 21 write-in votes.

The college punk band "Nasty Bozos '84" hosted the event and performed during the announcement. Earlier that day, Bozo creator Larry Harmon appeared on the Today Show, explaining that he went into children's television to become a "doctor of humor, love, peace, and understanding in this world." He further described his decision to run for President, against Ronald Reagan (R) and Walter Mondale (D), as a response to media calls to "put the real Bozo in the White House." It was reported that two assassination attempts were made on Bozo's life, but maybe just comedy. Harmon was never at a loss for ideas regarding promoting Bozo. Arizona was the only state to report the number of votes for Bozo, which turned out to be only 21 write-in votes.

The most significant change occurred in 1984 with the retirement of Bob Bell, with the show still the most-watched in its timeslot and a ten-year wait for studio audience reservations. After a nationwide search, Bell was replaced by actor Joey D'Auria, who would play the role of Bozo for the next 17 years.

In 1985, Frazier Thomas died, and Hurley filled in as host for the final six shows that season, stepping into a semi-authority character. In 1987, Hurley was dropped, and the show's timeslot returned to 60 minutes. In 1987, a synthesizer, played by "Professor Andy" (musician/actor Andy Mitran), replaced the three-piece Big Top Band.

Immel was replaced by Robin Eurich as "Rusty the Handyman," Michele Gregory as "Tunia," and Cathy Schenkelberg as "Pepper." In 1996, Schenkelberg was dropped. The show suffered another blow in 1997 when its format became educational following a Federal Communications Commission mandate requiring broadcast television stations to air at least three hours of educational children's programs per week. In 1998, Michele Gregory left the cast following more budget cuts.

In 2001, station management controversially ended production, citing increased competition from newer children's cable channels. The final taping, a 90-minute primetime special titled Bozo: 40 Years of Fun!, was taped on June 12, 2001, and aired on July 14, 2001. It was the only Bozo show that remained on television by this time. The special featured Joey D'Auria as Bozo, Robin Eurich as Rusty, Andy Mitran as Professor Andy, Marshall Brodien as Wizzo and Don Sandburg as Sandy. Also present at the last show were Billy Corgan of The Smashing Pumpkins, who performed, and Bob Bell's family. Many costumes and props are on display at The Museum of Broadcast Communications. Reruns of The Bozo Super Sunday Show aired until August 26, 2001. Bozo returned to television on December 24, 2005, in a two-hour retrospective titled Bozo, Gar & Ray: WGN TV Classics. The primetime premiere was #1 in the Chicago market and continues to be rebroadcast and streamed live online annually during the holiday season.

Bozo also returned to Chicago's parade scene and the WGN-TV float in 2008 as the station celebrated its 60th anniversary. He also appeared in a 2008 public service announcement alerting WGN-TV analog viewers about the upcoming switch to digital television. Bozo was played by WGN-TV staff member George Pappas. Since then, Bozo continues to appear annually in Chicago's biggest parades.

Few episodes from the show's first two decades survive; although some were recorded to videotape for delayed broadcasts, the tapes were reused and eventually discarded. In 2012, a vintage tape was located on the Walter J. Brown Media Archives & Peabody Awards Collection website archive list by Rick Klein of The Museum of Classic Chicago Television, containing material from two 1971 episodes. WGN reacquired the tape and created a new special entitled "Bozo's Circus: The Lost Tape," which aired in December 2012.

On October 6, 2018, Don Sandburg, Bozo's Circus producer, writer, and the last surviving original cast member, passed away at 87. Four months later, WGN-TV paid tribute to Sandburg and the rest of the original cast with a two-hour special titled "Bozo's Circus: The 1960s."

In 1975, Bob Trendler retired from television, and his Big Top Band was reduced to a three-piece band led by Tom Fitzsimmons. Locke also retired from television in 1976 and was replaced by Frazier Thomas, host of WGN's Family Classics and Garfield Goose and Friends. At that point, Garfield Goose and Friends ended its 24-year run on Chicago television with the puppets moving to a segment on Bozo's Circus. As the storyline went, Gar "bought" Bozo's Circus from the retiring Ringmaster Ned and appointed "Prime Minister" Thomas as the new Circus Manager. In 1978, when WGN-TV became a national superstation on cable and satellite through what is now WGN America, the show gained more of a national following.

|

| Wizzo and Bozo in the late 70s. |

TV Powww!Withh Frances Eden of WKPT (c.1980)

By 1980, Chicago's public schools stopped allowing students to go home for lunch, and Ray Rayner announced his imminent retirement from his morning show and Chicago television. The show stopped issuing tickets; the wait to be part of the audience was eight years long.

The following year, beginning a summer hiatus and airing taped shows pushed the ticket wait time back to ten years. On August 11, 1980, Bozo's Circus was renamed "The Bozo Show" and moved to weekdays at 8:00 AM, on tape, immediately following Ray Rayner and His Friends. On January 26, 1981, The Bozo Show replaced Ray Rayner and His Friends at 7:00 AM. The program expanded to 90 minutes, the circus acts and Garfield Goose and Friends puppets were dropped, and Cuddly Dudley (a puppet on Ray Rayner and His Friends voiced and operated by Roy Brown) and more cartoons were added. In 1983, Pat Hurley from ABC-TV's "Kids Are People Too" joined the cast as himself, interviewing kids in the studio audience and periodically participating in sketches.

On May 1, 1984, Larry Harmon, as Bozo the Clown, announced his write-in candidacy for President of the United States. That afternoon, dressed as Bozo, he arrived at Columbia University in a 1977 Cadillac limousine accompanied by "secret service" men wearing suits, sunglasses, and red clown noses.

The most significant change occurred in 1984 with the retirement of Bob Bell, with the show still the most-watched in its timeslot and a ten-year wait for studio audience reservations. After a nationwide search, Bell was replaced by actor Joey D'Auria, who would play the role of Bozo for the next 17 years.

|

| Bob Bell sadly retired from his position as Bozo in 1984, and with that decision, an end of a wonderful era in Chicago Broadcasting occurred. An incredible special aired on WGN-TV entitled "Bob Bell: The Man Behind The Makeup" gave insight into a man we knew very little about. |

Roy Brown began suffering heart-related problems and was absent from the show for an extended period during the 1991–92 season. This coincided with the show's 30th anniversary and a reunion special that included Don Sandburg as Sandy, who also filled in for Cooky for the first two weeks that season. Actor Adrian Zmed (best known from ABC-TV's TJ Hooker), a childhood fan of Bozo's Circus and former Grand Prize Game contestant, also appeared on the special and portrayed himself as a "Rookie Clown" for the following two weeks. Actor Michael Immel then joined the show as "Spiffy" (Spifford Q. Fahrquahrrr). Brown returned in January 1992, initially on a part-time basis but suffered additional health setbacks and took another extended leave of absence in the fall of 1993.

However, Brown's presence on the show remained, as previously aired segments as Cooky and Cuddly Dudley were incorporated until 1994, when he and Marshall Brodien retired from television.

Later that year, WGN management decided to get out of the weekday children's television business and buried The Bozo Show in an early Sunday timeslot as The Bozo Super Sunday Show on September 11, 1994.

WGN's decision to relegate the program to Sundays coincided with the launch of the WGN Morning News (which debuted five days earlier), a weekday morning newscast initially launched as a one-hour program. Moving the Bozo Show resulted in the cancellation of WGN's 2-year-old Sunday morning newscast, whose 8 AM timeslot went to Bozo.

Immel was replaced by Robin Eurich as "Rusty the Handyman," Michele Gregory as "Tunia," and Cathy Schenkelberg as "Pepper." In 1996, Schenkelberg was dropped. The show suffered another blow in 1997 when its format became educational following a Federal Communications Commission mandate requiring broadcast television stations to air at least three hours of educational children's programs per week. In 1998, Michele Gregory left the cast following more budget cuts.

In 2001, station management controversially ended production, citing increased competition from newer children's cable channels. The final taping, a 90-minute primetime special titled Bozo: 40 Years of Fun!, was taped on June 12, 2001, and aired on July 14, 2001. It was the only Bozo show that remained on television by this time. The special featured Joey D'Auria as Bozo, Robin Eurich as Rusty, Andy Mitran as Professor Andy, Marshall Brodien as Wizzo and Don Sandburg as Sandy. Also present at the last show were Billy Corgan of The Smashing Pumpkins, who performed, and Bob Bell's family. Many costumes and props are on display at The Museum of Broadcast Communications. Reruns of The Bozo Super Sunday Show aired until August 26, 2001. Bozo returned to television on December 24, 2005, in a two-hour retrospective titled Bozo, Gar & Ray: WGN TV Classics. The primetime premiere was #1 in the Chicago market and continues to be rebroadcast and streamed live online annually during the holiday season.

Bozo also returned to Chicago's parade scene and the WGN-TV float in 2008 as the station celebrated its 60th anniversary. He also appeared in a 2008 public service announcement alerting WGN-TV analog viewers about the upcoming switch to digital television. Bozo was played by WGN-TV staff member George Pappas. Since then, Bozo continues to appear annually in Chicago's biggest parades.

Few episodes from the show's first two decades survive; although some were recorded to videotape for delayed broadcasts, the tapes were reused and eventually discarded. In 2012, a vintage tape was located on the Walter J. Brown Media Archives & Peabody Awards Collection website archive list by Rick Klein of The Museum of Classic Chicago Television, containing material from two 1971 episodes. WGN reacquired the tape and created a new special entitled "Bozo's Circus: The Lost Tape," which aired in December 2012.

On October 6, 2018, Don Sandburg, Bozo's Circus producer, writer, and the last surviving original cast member, passed away at 87. Four months later, WGN-TV paid tribute to Sandburg and the rest of the original cast with a two-hour special titled "Bozo's Circus: The 1960s."

"WHO'S YOUR FAVORITE CLOWN?"

URBAN MYTH: Krusty the Clown was based on Bozo.MYTH BUSTED: Krusty the Clown was created by cartoonist Matt Groening and partially inspired by Rusty Nails, a television clown from Groening's hometown of Portland, Oregon. He was designed to look like Homer Simpson with clown makeup, with the original idea being that Bart worships a television clown who was actually his own father in disguise. Bob Bell (1960-1984), Bozo the Clown, whose voice was later the pattern for that of Krusty the Clown. Krusty made his television debut on January 15, 1989, in The Tracey Ullman Show short "The Krusty the Clown Show." Krusty then was on The Simpsons sitcom, which began on December 17, 1989.

WGN-TV CHICAGO BOZO ACTORS AND YEARS

Bozo the Clown Bob Bell 1960–1984

Oliver O. Oliver Ray Rayner 1961–1971

Sandy Don Sandburg 1961–1969

Ringmaster Ned Ned Locke 1961–1976

Mr. Bob Bob Trendler 1961–1975

Cooky Roy Brown 1968–1994

Wizzo Marshall Brodien 1968–1994

Elrod T. Potter Pat Tobin 1971–1972

Clod Hopper John Thompson 1972–1973

Frazier Thomas Himself 1976–1985

Pat Hurley Himself 1983–1987

Bozo the Clown Joey D'Auria 1984–2001

Professor Andy Andy Mitran 1987–2001

Spiffy Michael Immel 1991–1994

Rusty Robin Eurich 1994–2001

Pepper Cathy Schenkelberg 1994–1996

Tunia Michele Gregory 1994–1998

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

[1] TV POWWW! It was a franchised television game show format in which home viewers controlled a video game via telephone in hopes of winning prizes.

TV Powww!With Frances Eden of WKPT (c.1980)

The TV POWWW format, produced and distributed by Florida syndicator Marvin Kempner, debuted in 1978 on Los Angeles station KABC-TV as part of A.M. Los Angeles, and by the start of the next decade, was seen on 79 local television stations (including national superstation WGN as part of Bozo's Circus) in the United States, as well as several foreign broadcasters. While most stations had dropped TV POWWW by the mid-1980s, stations in Australia and Italy were still using it as late as 1990.Stations were initially supplied with games for the Fairchild Channel F console, but following Fairchild's withdrawal from the home video game market, Intellivision games were used. Kempner unsuccessfully attempted to interest both Nintendo and Sega in a TV POWWW revival.While the underlying technology was standardized across participating stations, TV POWWW's presentation format varied from market to market. Many presented TV POWWW as a series of segments that ran during the commercial breaks of television programming (a la Dialing for Dollars), while some (such as KTTV in Los Angeles) presented TV POWWW as a standalone program.GameplayIn the video game being featured, the at-home player would give directions over the phone while watching the game on their home screen. When the viewer determined that the weapon was aiming at the target, they said, "Pow!" after which that weapon would activate.Accounts vary as to what kind of controller technology was involved. Some sources state that the gaming consoles sent to the stations were modified for voice activation. However, a 2008 WPIX station retrospective claimed that for the station's version, where the player said "Pix" (Pron: picks), an employee in the control room manually hit the fire button when the caller indicated a shot.One of the pitfalls of the gameplay was that, due to broadcasting technicalities, there was a significant lag in the transmission of a television signal. The player would experience this lag when playing at home, which likely made playing the game somewhat more difficult.