Calhoun set up shop in a building on Clark Street. Like anyone who owned a printing press in 1833, he depended on job-lot printing orders to make his living. The newspaper was more of a sideline for Calhoun, a vehicle to publicize his personal views.

Andrew Jackson, a Democrat, was president. The opposition party was called the Whigs. But the feature story in the first issue of the Chicago Weekly Democrat was not a political manifesto. Instead, it was an account of a powwow between two Indian tribes, the Sioux and the Sac-and-Fox.

And that tells you something about the newspaper business in those times. Calhoun had copied the whole powwow story from a St. Louis paper. Was this plagiarism? There weren't any wire services yet, so editors got their out-of-town news by lifting it from other papers.

The one-piece of original work was the editorial. There Calhoun came out boldly in favor of building a canal or railroad to link Lake Michigan and the Mississippi River. Oddly enough, that was the type of editorial you'd expect to find in a Whig paper, not in a paper calling itself the Democrat.

Calhoun continued to publish, with some interruptions.

Publishing a newspaper on the frontier was very challenging. In May of 1835, Calhoun issued a second prospectus that apologized for the paper's virtual disappearance over the previous four months and promised a new editor would upgrade the quality of news when the Chicago Weekly Democrat re-appeared. He cited a lack of available paper on which to print during the winter of 1834-1835. He did not cite, but presumably was responding to, the appearance of his first competition, the Chicago's American Newspaper (sponsored by a rival political party, the Whigs).

The monopoly of the Chicago Weekly Democrat ended in 1835 when T.O. Davis established The American, a Whig paper. To fight this competitor, Calhoun hired James Curtiss as the new editor of the paper. Daniel Brainard was also associated with editing the paper at some point in these early years. By May 1836 Calhoun had lost interest in the paper and attempted to sell it to a group of local Democrats, but the sale fell through.

The paper was enlarged in August 1836. The last issue was published on November 16, 1836, and afterward, the paper was sold to Isaac Hill, who sold it to Long John Wentworth.

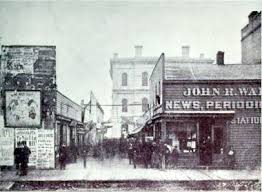

Wentworth had become a member of the new Republican Party (founded in 1854) by the end of the 1850s — a turnabout that can be said, with some oversimplification, to have resulted from the politics of the years before the Civil War (1861-1865) when feelings about slavery caused shifting alliances and political turmoil throughout the country.

In 1861, just before the Civil War started it the end of April, Wentworth closed the Chicago Weekly Democrat. He said he was tired from his recent term as Chicago mayor and unable to continue after the death of his assistant, David Bradley. Others speculated he did not care to invest the money it would take to modernize the newspaper and adequately cover the war many expected at any moment.

A more pressing cause was a $250,000 libel lawsuit by another of Chicago's Old Settlers, J. Young Scammon. Scammon was angry because Wentworth had published a cartoon depicting him as a "wildcat" banker (the fat cat in his cartoon wore a pair of Scammon's distinctive spectacles). Wentworth gave his subscription list to the Chicago Tribune, whose publishers induced Scammon to drop the suit in return.

Wentworth's political career went on but his paper was gone; although his own complete run of all the Chicago Weekly Democrat newspapers was destroyed in the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.

|

| The east/west alley between Madison and Washington Streets and from State Street to Wacker Drive was known as "Newspaper Alley." |

It was lastly nicknamed "Newspaper Alley" before being renamed for the last time to Calhoun Place. Other nicknames before Newspaper Alley included, from newest to oldest, were; Newsboy's Alley, Gamblers Alley, and Whitechapel Alley.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.

Compiled by Dr. Neil Gale, Ph.D.